Working Backwards: Insights, Stories, and Secrets from Inside Amazon

By Colin Bryar and Bill Carr | Macmillan | $34.99 | 286 pages

No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention

By Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer | WH Allen | $35.00 | 293 pages

The Tech Boom’s winners are writing corporate cookbooks. These two offer recipes with some similarities and many differences.

Amazon and Netflix are giants of the online economy. Both launched in the 1990s and survived the Tech Wreck of the early 2000s. Amazon is now an uber-giant, one of five US firms with a market capitalisation of more than US$1 trillion at the time of writing; Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet/Google and Facebook are the others. At around US$240 billion, Netflix is much smaller, though still among the largest twenty-five US companies.

For the authors of these books, innovation and invention are the markers of the two enterprises and the era they inhabit. “In the industrial era, the goal was to minimise variation,” says Netflix’s Reed Hastings. Today, in the information age, in creative companies, “maximising variation is more essential.” “Creativity, speed and agility” rather than “error prevention and replicability” are the goals for “many companies and… many teams.”

Yet the authors also attribute the two companies’ success to the steadiness and clarity of their central missions: Amazon’s belief that the long-term interests of shareholders coincide with the interests of customers, its obsession with customers rather than competitors, its “willingness to think long-term,” its “eagerness to invent” and its pride in “operational excellence.” Netflix too is “highly aligned,” concentrated on what Hastings calls “Our North Star,” “building a company that is able to adapt quickly as unforeseen opportunities arise and business conditions change.”

Pursuing these steady visions over more than two decades, Amazon and Netflix have radically changed what they do. An online bookstore became “The Everything Store,” as journalist Brad Stone titled his first book about Amazon. (His second, Amazon Unbound, was published earlier this year.) It started manufacturing and selling its own products, hosting other sellers, and selling services it built for itself to external parties. Amazon Web Services is now a behemoth in its own right. Netflix began as a DVD rental company that licensed other companies’ movies and TV shows, before moving into online streaming and producing its own Netflix Originals.

These were not mere pivots, they were deeply transforming, changing fundamentally the staff skills, the organisational competencies and the business partners needed for success. At the same time, both enterprises moved beyond the United States, seeking online customers, dealing with regulatory and political challenges, sometimes establishing distant operations and employing local people. Globalising the businesses massively increased their size and complexity. It also expanded the potential audience for books like these that try to explain the secret sauces.

Both books bring some outside perspective to what are essentially insider accounts. Colin Bryar and Bill Carr had long careers at Amazon before co-founding a business where they “coach executives at both large and early-stage companies on how to implement the management practices developed at Amazon.” They are writing, in part, for potential clients.

No Rules Rules is about the company Reed Hastings co-founded, and is co-written by him and Erin Meyer — actually, it is a kind of dialogue constructed by alternating, individually written sections. Meyer is an “American living in Paris” who has worked with Netflix and conducted a lot of interviews with staff for this book. A professor at INSEAD Business School’s Fontainebleau campus, she explores “how the world’s most successful managers navigate the complexities of cultural differences in a global environment.” Hastings, one suspects, wants this book to help attract talented staff to the fluid, personally rewarding organisation it portrays.

“Working Backwards” is the title of Bryar and Carr’s business as well as their book. It refers to the Amazon creed: don’t create a product and then try to sell it; start with the customer experience then work backwards to the design and marketing. No Rules Rules is a stretch, for Hasting and Meyer’s book is as much about the rules Netflix does have, and how they are enforced, as those it has let go.

The pictures that eventually emerge are the obverse of the ones painted by two of the companies’ best-known incidents, both involving PowerPoint. Netflix’s organisational culture began attracting attention because of the massive, 127-slide Netflix Culture Deck, first shared outside the organisation in 2009. Amazon memorably banned PowerPoint for internal presentations in 2004 after CEO Jeff Bezos and co-author Colin Bryar read Edward Tufte’s essay condemning the “cognitive style” of that ubiquitous presentation software. Complex, interconnected discussions were not well served by the relentless linearity of bullet points. In PowerPoint’s place came the “six-pager,” a short narrative format still used to “describe, review or propose just about any type of idea, process or business” at Amazon. Everyone has to write them and read them.

Working Backwards, though, exalts the universal application of procedures. No Rules Rules celebrates their elimination. The approaches have more in common than it seems, but they are undoubtedly distinctive mindsets to bring to the task of innovation and invention.

Exalting procedure, Bryar and Carr explain the “Bar Raiser” hiring process, “single-threaded teams” as an organising principle, and the PR/FAQ (Press Release/Frequently Asked Questions) process that Amazon uses for new product development. The PR/FAQ embodies the idea of “working backwards.” What would you say when the time came to launch this new product? What questions would customers ask and how would you answer them?

They also set out Amazon’s fourteen leadership principles — among them: “Leaders are owners… Leaders are right a lot… Leaders are never done learning… Leaders listen attentively, speak candidly and treat others respectfully… Leaders do not compromise for the sake of social cohesion… Leaders rise to the occasion and never settle.”

The most striking apparent contrast with Netflix comes from Amazon’s Deep Dive Leadership Principle: “Leaders operate at all levels, stay connected to the details, audit frequently, and are sceptical when metrics and anecdotes differ. No task is beneath them.” Bryar and Carr add: “At many companies, when the senior leadership meets, they tend to focus more on big-picture, high-level strategy issues than on execution. At Amazon, it’s the opposite. Amazon leaders toil over the execution details.”

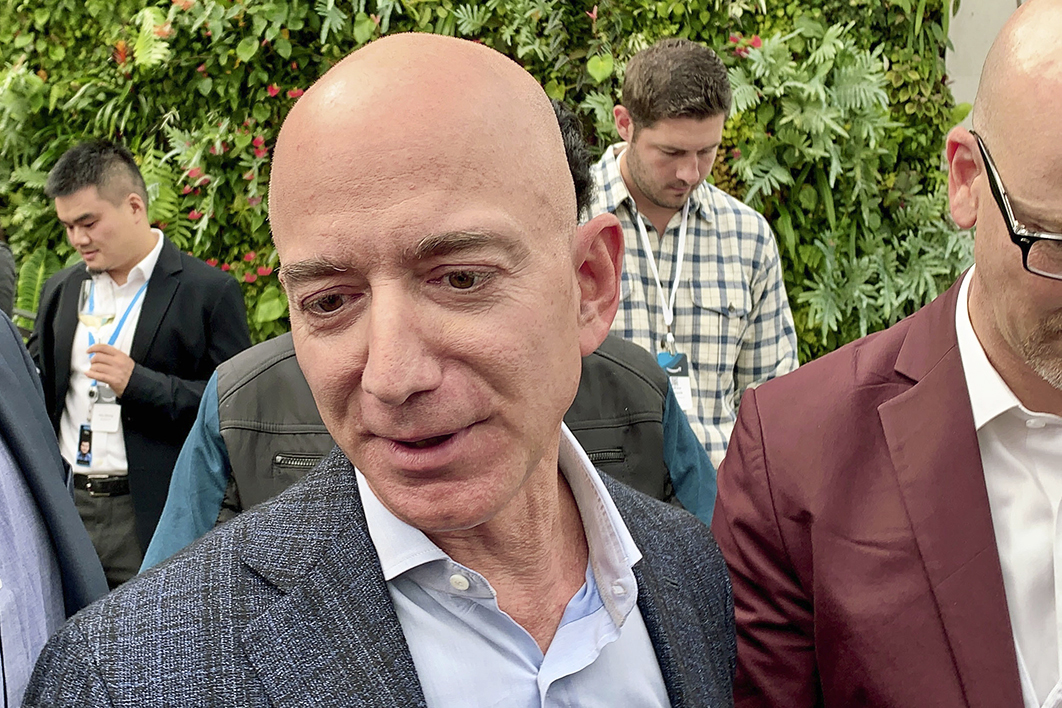

In this, founding CEO Jeff Bezos looms large. Bezos recently stepped down as CEO, his place taken by former head of Amazon Web Services, Andrew Jassy, though he remains executive chairman and Amazon’s largest shareholder. He was clearly a “nanomanager,” Hastings and Meyer’s term for the mythological CEOs who are said to be “so involved in the details of the business that their product or service becomes amazing.” Working Backwards is dense with references to Jeff: Jeff’s ideas, Jeff’s comments at meetings, Jeff’s early-morning emails after “walking the store,” Jeff’s unhappiness about this or delight about that.

Celebrating the elimination of rules, Hastings says, “We don’t emulate these top-down models, because we believe we are fastest and most innovative when employees throughout the company make and own decisions.” He is proud of the comment Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg made after shadowing him for a day: “You didn’t make one decision!” The idea is “to lead by context, not control.” The image of the organisational structure is a tree rather than a pyramid. The CEO sits “all the way down at the roots”; the decision-makers are “informed captains up at the top branches.”

An example: CEO Hastings, “at the roots,” sets the overall strategy for Netflix to make international expansion its number one priority. Ted Sarandos, chief content officer and now co-CEO, “at the trunk,” encourages his teams to take big risks with large potential wins or lessons-from-failure in those new territories: “We need to become an international learning machine.” Out on a “big branch,” vice-president of original animation, Melissa Cobb, decides the foray into children’s programming should mean a child watching Netflix in a Bangkok high-rise should not get the typical “global” mix of either local or US characters, but “a variety of TV and movie friends from around the world.” On a mid-sized branch, the director of the team acquiring preschool content, Dominique Bazay, decides Netflix’s animation needs to be high-quality, high enough “to be a hit in anime-obsessed Japan.” The manager of content acquisition in Mumbai, “on a small branch,” “in a small conference room in Mumbai,” commissions Mighty Little Bheem, spending a lot of money on a genre that has few precedents in India.

It is rarely difficult to poke fun at management books — at the language, the inconsistencies, the conviction that none of this has ever been done before, the confident assumption that lessons from one stellar organisation are applicable to all others.

Here, Bryar and Carr refer often to the virtues of “being Amazonian.” This is what happens when you exhibit one or more of the fourteen leadership principles. When things go well, it is because people are “being Amazonian,” sometimes without even realising it. When something goes wrong, invariably, someone, somewhere, was insufficiently Amazonian.

Netflix preaches candour and transparency about data inside the company, but has pioneered a radical degree of opacity about its own viewing numbers by comparison with the historical standards set by cinemas and television broadcasters. The company asserts its inclusivity but insists on “no jerks” — the kind of No Rules Rule that probably seems fair and obvious to incumbent non-jerks but which, one suspects, may hide unwritten sub-rules that mystify the excluded. There are no detailed rules about travel and expenses, but 10 per cent of claims are audited and if people are found to have infringed the one, overarching rule — “act in Netflix’s best interests” — well, “fire them and speak about the abuse openly.”

Innovation, of course, did not begin with the internet; Amazon did not invent customer-centric product development; leaders and organisations have been grappling forever with the balance between centralised “command and control” and decentralised autonomy. The people who laid the first Atlantic cable a century and a half ago, or launched the first aviation services, risked not just financial ruin but levels of personal danger some way beyond the life experience of Silicon Valley engineers running A/B tests of discounted shipping options.

Even working backwards seems to have had many parents. Just returned to Apple as an adviser in 1997, Steve Jobs told the Worldwide Developer Conference in 1997, “One of the things I’ve always found is you’ve got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology. I’ve made this mistake probably more than anybody in this room and I’ve got the scar tissue to prove it.”

But there are two full litres of Kool-Aid here in these two books and you don’t have to drink it all to find much of it fascinating. Erin Meyer first thought the Netflix Culture Deck was “hypermasculine, excessively confrontational, and downright aggressive — perhaps a reflection of the kind of company you might expect to be constructed by an engineer with a somewhat mechanistic, rationalist view of human nature.” She accepted the invitation to take a closer look because what could not be denied was the scale of Netflix’s success. It’s “beyond unusual. It’s incredible. Clearly, something singular is happening.” Beyond unusual, yes, but perhaps not singular, because Amazon could say the same, at least about its growth.

Both pairs of authors obviously believe the recipes they reveal might be usefully applied to other organisations and situations, but they acknowledge limits, even in their own. They talk about failures, like Amazon’s 2014–15 Fire Phone, as well as successes. Hastings admits some people will take advantage of the absence of rules. Netflix staff probably fly business class more often than is really needed to “serve Netflix’s best interests” by arriving fresher for meetings. But “even if your employees spend a little more when you give them freedom, the cost is still less than having a workplace where they can’t fly… If you limit their choices, you’ll lose out on the speed and flexibility that comes from a low-rule environment.” The biggest risk for Netflix “isn’t making a mistake or losing consistency; it’s failing to attract top talent, to invent new products, or to change direction quickly when the environment shifts.”

No Rules Rules concludes with a frank acknowledgement of the continuing relevance of the “rules with process” model for some organisations and activities (even parts of Netflix itself), and a set of questions to ask in order to select the right approach. “If you’re leading an emergency room, testing airplanes, managing a coal mine, or delivering just-in-time medication to senior citizens,” “rules with process is the way to go.” Erin Meyer has worked with a few old economy stalwarts that might qualify, like ExxonMobil, Michelin and Johnson & Johnson, as well as with financial institutions like BNP Paribas and Deutsche Bank, whose stumbles during the global financial crisis showed how difficult it is to draw neat boundaries around the innovative, fail-fast parts of many organisations and the mission-critical operations where mistakes matter.

The large omission from both books is any real sense of the relationship between these two huge and influential organisations and the wider world. This may seem an unreasonable demand for books of this kind. But there is a clue at the start of the movie awarded Best Film at this year’s Academy Awards, Nomadland: those opening scenes of the Amazon “fulfilment centre” in the snow, juxtaposing warm, high-tech efficiency inside with the human desolation outside. We do need to insist on large questions being posed about “America,” its Tech Boom and its patchwork prosperity, the “sort of affluent dysfunction” that Janan Ganesh described recently in the Financial Times.

Bryar and Carr mention this at the outset: “Some take issue with Amazon’s impact on the business world and even on our society as a whole.” Although “obviously important, both because they affect the lives of people and communities and because, increasingly, failure to address them can have a serious reputational and financial impact on a company,” these issues are “beyond the scope of what we can cover in-depth in this book.” Relentless about the detail of so many aspects of its products, Amazon has been playing catch-up on matters as big as the living and working conditions of its people and the environmental footprint of its activities. The Working Backwards authors footnote Jeff Bezos’s April 2020 letter to shareholders, which “did address Amazon’s impact on multiple fronts.”

The Netflix that Hastings and Meyer portray is a remarkable island of “stunning colleagues,” candour and flexibility. It aspires to be a professional sports team rather than a family. People stay as long as they are the best available for their roles and are moved on as soon as they are not.

Early in No Rules Rules, Hastings tells the story of Netflix’s survival through the Tech Wreck — the dot-com crash — a “road to Damascus experience” that founded “much that has led to Netflix’s success.” The company had to let forty of its 120 staff go. It was gruelling but the company prospered. Business grew and the smaller, now more densely talented team worked longer hours and got the job done. “Talented people,” says Hastings, “make one another more effective.” “Talent density” became a Netflix lodestar.

I found myself wanting to know more about those forty people, good people apparently, just not good enough: “A few were exceptionally gifted and high performing but also complainers or pessimists.” Maybe they found other roles elsewhere for which they were better suited. They are no longer on Netflix’s balance sheet but they are probably still on the United States’. If we are to fully grasp the impact of these tech giants on the whole world, not just their own, we need to understand more than the winners. •