Having not been able to see a film in a cinema for quite some time, I have been grateful for SBS On Demand screenings, among them Jonathan Teplitzky’s Churchill, released in 2017 and now available on Amazon Prime and elsewhere, and John Fleet’s 2019 documentary, Churchill and the Movie Mogul, which was shown at the Jewish Film Festival earlier this year, and can now be seen on Vimeo.

The many representations of the irascible, inspirational Winston Churchill on screens large and small have featured actors including Robert Hardy, Albert Finney, Gary Oldman, Brian Cox and Ian McNeice (Bert Large of Doc Martin fame) in the lead role, each of them finding his own way of coming to terms with possibly the most famous British politician of the past century.

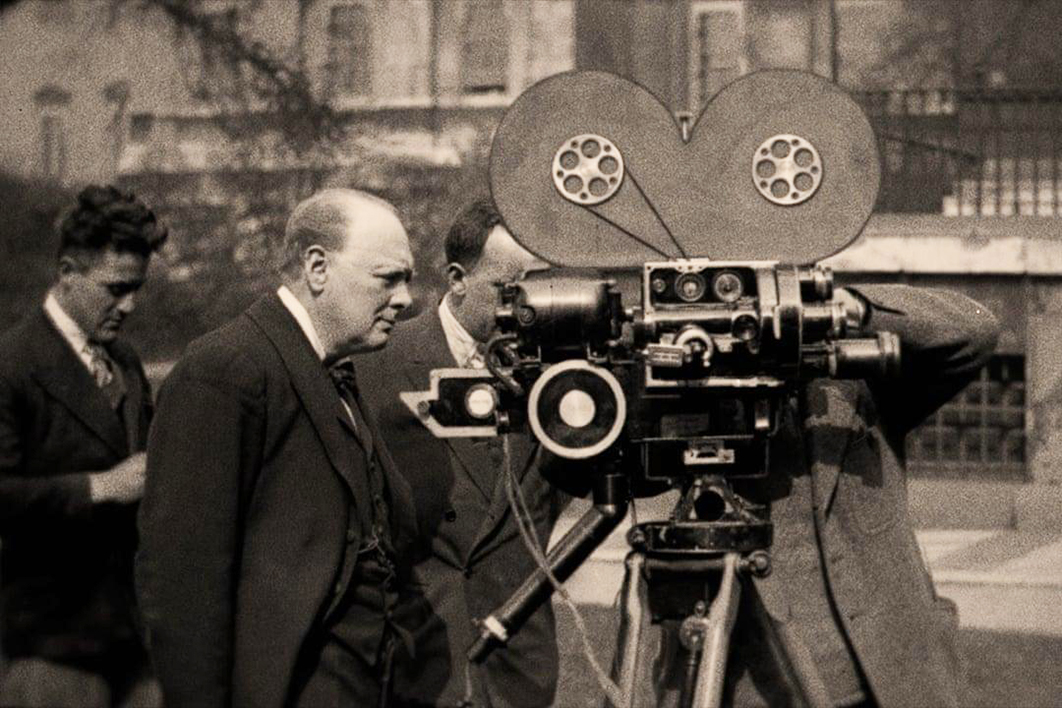

But how many of us know much about Churchill’s involvement in the film industry? Fleet’s documentary goes some way to filling this lacuna.

Churchill and the Movie Mogul’s other protagonist is Alexander Korda, whose poverty-stricken Hungarian childhood didn’t stop him from becoming the most powerful producer in 1930s England, creating such international successes as The Private Life of Henry VIII. Churchill’s long association with Korda began in that decade, and Fleet’s film investigates how the two men came to see film as the best medium for promoting the British cause as the crisis in Europe deepened. This aim became more pressing, of course, as the threat of war became more ominous in the later thirties. And once the war was under way they saw films as even more crucial in making England matter more to the United States, which Churchill hoped to enlist on Britain’s side.

To do this, he felt it was crucial to send Korda across the Atlantic to make films that would create sympathy for Britain’s war aims. This resulted in what became Churchill’s favourite film, Lady Hamilton (1941) — more provocatively titled That Hamilton Woman in America, though neither title suggests that Lord Nelson, Lady Hamilton’s foil in the film, would get much of a look-in. Having often been a key adviser to Korda, Churchill saw parallels between England’s situation at the start of the war and its spectacular defeat of the Spanish Armada, celebrated in an earlier Korda film, Fire Over England (1937). Indeed, he increasingly came to see film as a “war weapon.”

Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor obviously played the key role in getting the Americans to the battlefront, but Fleet’s film suggests that we shouldn’t underestimate the effects of the Churchill–Korda offensive. One of the history-changing moments he recounts is a crucial meeting between Churchill and Roosevelt, recalled in the film by son Elliott Roosevelt.

Though documentary is an appropriate label for Churchill and the Movie Mogul, it’s not just a careful recital of facts. Fleet creates a sense of ongoing drama, drawing on a variety of sources and methods of presentation. Helping create that sense of drama are plenty of clips from the key films; for example, the moment from Fire Over England when Flora Robson as Elizabeth I makes her famous (and not terribly politically correct) remark, “I may have the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king.” We see audiences watching the films with rapt attention, and even cars lined up at an early drive-in, along with clips from the newsreels of the time. Commentators across an impressive range, including Stephen Fry, James Mason and Vivien Leigh, discuss Korda as producer, director and major figure in British film history, and politicians, academics and critics assess one or other of the two men.

The film is as much about Korda as it is about Churchill, and they get roughly equal screen time. Churchill and the Movie Mogul vividly evokes time, place and its protagonists.

I wouldn’t say that the Churchill we view in Jonathan Teplitzky’s Churchill is necessarily true to the life in every detail. Nor does the film, though an absorbing enough entertainment, always stick to the historical facts. I’m recommending it here as drama, not as documentary.

The film’s historical moment is that of the days leading up to the Normandy landing, Operation Overlord, or D-Day as it became known, on 6 June 1944. Its narrative impulse lies in Churchill’s approach to the operation and how it influences his dealings with the US supreme Allied commander, General Eisenhower, and with Field Marshal Montgomery and others. These others include his wife Clementine (Miranda Richardson) and King George VI (James Purefoy).

When we first see Churchill he is wandering, in a long shot, along a beach, presumably pondering the challenges of liberating France. This vista contrasts with our next view of him, as the camera prowls through his wildly untidy bedroom, littered with papers, cigar butts and whisky glasses.

Teplitzky is interested in evoking his dealings with staff, including a new secretary whose fiancé will have a moment in the landing — and here the film gives Churchill a touching if perhaps slightly soapy moment. There is clear conflict between Churchill, who is portrayed as opposing the D-Day landing, and Eisenhower and Montgomery. Clashes at this military level lead to a meeting with the King, who tells Churchill he “must stay at home and wait.”

However factually accurate, Teplitzky’s film weaves the public and the private to construct a persuasive entertainment that is also occasionally moving as it proceeds inexorably to the famous Churchill phrase, “We shall never surrender.”

I should mention that Teplitzky’s film led me to view two of the many other films based on the cantankerous character who ultimately led Britain to victory against the German military predator: Richard Loncraine’s 2002 TV movie, The Gathering Storm, and Joe Wright’s 2017 film, Darkest Hour. What all three movies have in common is their focus on Churchill’s dealings with a key moment in the second world war — and his relations with his wife Clemmie.

He somehow contrived, in Churchill, to make the D-Day landing redound to his credit despite his earlier opposition. In Darkest Hour, despite a snide reference to his role in promoting the Gallipoli landing during the first world war, Churchill (Gary Oldman) pushes parliament into evacuating from Dunkirk, following which he receives wildly enthusiastic support. In The Gathering Storm, we watch Churchill (Albert Finney) move from a career low point in 1934 to the triumph of taking over from Chamberlain to become the prime minister who would lead the nation to war — and repudiate the criticism of his “mindless optimism.”

In both Loncraine’s and Wright’s films, he is depicted in querulous dealings with various politicians — whether it is Stanley Baldwin (Derek Jacobi), whom he harasses in The Gathering Storm, or Neville Chamberlain, up till the latter’s announcement that “We are at war with Germany,” in Darkest Hour — and numerous others who cross his path. As well as these public manifestations of an imposing but somewhat despotic temperament, the films also offer entertaining insights into his married life with Clemmie, played respectively and superbly by Vanessa Redgrave and Kristin Scott Thomas. Each of them works hard at bearing with his outrages, and each makes credible an underlying devotion.

No doubt, all three feature films sometimes play fast and loose with the facts — a privilege not available to John Fleet — but their portraits of the charismatic and maddening central figure are of a high order, and in each film there is a pervasive sense of a nation at some of its most challenging times. •