Queer history in Australia received a considerable fillip recently with the broadcast of the three-part series Queerstralia by the ABC. Timed to coincide with WorldPride in Sydney in February–March, its upbeat and affirming style treats the troubled aspects of queer history with a relatively light touch. It was another demonstration that the energy in queer history tends to form around legal reform and the advancement of LGBTQIA+ rights from the 1970s onwards.

To research and write queer history before living memory — without oral testimony, that is — is to enter a much darker place. The last man to hang for sodomy in the British Empire was in Tasmania in 1867, and in 1997 Tasmania became the last Australian jurisdiction to decriminalise male homosexuality. Relationships and life choices that are criminalised, stigmatised and pathologised are unlikely to leave much of an imprint on the public record, and surviving historical evidence is often patchy, obscure and cloaked in euphemism.

In 1990 I wrote an honours thesis in the history department of the University of Tasmania on the Tasmanian writer Roy Bridges. It wasn’t a piece of literary criticism, for that would have been a short thesis indeed. Most of Bridges’s thirty-six novels were adventure stories for boys or middle-brow historical romances and melodramas dealing with the early days of Tasmania and Victoria. Frequently he was inspired by stories his mother, Laura Wood, told of her family history on their farm near Sorell, east of Hobart, going back to the earliest days of white settlement.

Bridges was Tasmania’s most prolific novelist, successful and admired in his time, but his reputation didn’t outlast his death in 1952. I wasn’t interested in the quality of his writing so much as his interpretation of Tasmanian colonial history, and how his own deep connection with the island was refracted through his works of fiction and memoir.

Born in Hobart in 1885, Bridges started publishing in 1909, and at first wrote prolifically for the gutsy little New South Wales Bookstall Company. Time and again he sold his copyright for fifty pounds per novel, whenever he was hard up (“which was often,” he once observed), grateful for the support the Bookstall gave to new Australian writers.

In his mature period his novels were published in London by Hutchinson or Hodder and Stoughton, but during and after the second world war his output declined. The gratifying success of That Yesterday Was Home (1948) eased his final years. Part history, part family history and part memoir, the book is a passionately expressed meditation on memory and connection with place. He died in 1952.

Roy Bridges in 1937. Inscription reads, “To my friends at Robertson & Mullins. Roy Bridges. 1937.” State Library of Victoria

By the time I started work on Bridges he was remembered mainly by enthusiasts interested in the literary culture of Tasmania. As a thesis project, though, he was perfect. No one else was claiming him, and significant collections of his papers were held in libraries in Hobart, Melbourne and Canberra. Methodologically I had Bridges’s memoir as a guide, which, unreliable as any memoir always is — and I knew this — was at least a place to begin.

I bought a 1:25,000 map of the Sorell district and pinned it to my wall in the history department. I drove out to meet Bridges’s nephew and his family, who were still working the property that Bridges had named “Woods” after his mother’s family.

The town of Sorell has always been a stopping point for travellers from Hobart heading either to the east coast or to the convict ruins at Port Arthur. To get there you must first drive across Frederick Henry Bay via the Sorell causeway at Pittwater. “All my life,” Bridges wrote in 1948, “Frederick Henry Bay has sounded through my mind and imagination. Like drums… or like cannonade in storm, or in the frozen stillness of winter’s nights.”

Every time I drive across the Sorell causeway I think of him, and did so again one brilliant day in February this year while heading up to Bicheno on holiday. With the sun sparkling off the bay I shouldn’t have been brooding on old stories, but suddenly I knew that the time was right to tackle again a biographical dilemma I had evaded, all those years ago.

The few others who have written about Bridges have struggled to understand the source of the loneliness and sorrow which, towards the end, amounted to torment. His journalist friend C.E. (Ted) Sayers first met Bridges in 1922 and remembered him as a haunted, “tense little man,” a chain smoker, embarrassed in the company of women, who had allowed a streak of morbidity and violence to enter his fiction. I developed my own suspicions about this haunting, and in my thesis in 1990 I speculated, briefly and carefully (because this was Tasmania), that Roy Bridges had been a closeted and deeply repressed gay man.

I wouldn’t have thought of this except for a conversation I had with the one friend of Bridges I could still find, a well-known local historian named Basil Rait. I visited the elderly Mr Rait in a tumbledown house in north Hobart somewhere near Trinity Church. Just as I was deciding that his recollections weren’t going to be particularly useful, he astounded me with the remark that one day, Roy Bridges had been seen emerging from the Imperial Hotel on Collins Street in central Hobart, and that the Imperial was a known place for homosexual men to congregate.

When did this occur? And did Rait see this himself? I was too amazed — and too timid, I think — to ask enough questions and, rookie historian that I was, I did not record the conversation. Why was Rait so frank, and what did he think I would do with his information? Perhaps I’d gained his trust because I had arrived without a tape recorder. I don’t know.

But I did consider his revelation very carefully. The once-elegant Imperial was rather seedy by then, which seemed to lend plausibility to what Rait had said. I had gay friends and I asked if anyone knew anything about the Imperial’s reputation. No one did.

Unable to verify Rait’s assertion, I turned to the textual sources. Although I was aware of the danger of reading too much into odd snippets of evidence that might have signified nothing, I was also unwilling to ignore what I had been told, which, if true, might explain everything. To speculate about Bridges’s sexuality in the thesis, or not: my thesis supervisor left it up to me. On an early draft I can see in his handwriting: “You decide.”

Royal Tasman (Roy) Bridges came from a family of prosperous wicker manufacturers and retailers. His father Samuel and uncle James ran Bridges Brothers, in Elizabeth Street, Hobart, which had been founded in 1857 by their father, Samuel senior. After graduating with an arts degree from the University of Tasmania, Bridges joined the Tasmanian News as a cadet in December 1904. Journalism was his career for most of the next twenty-five years. He accepted a job with the Hobart Mercury in 1907 but soon became disaffected by poorly paid sixteen-hour days on what his memoir described as a “rotten sweat-rag” and headed for Sydney.

He got a job immediately on the Australian Star under its editor, Ralph Asher. Sydney was a relief from Hobart’s “superficial puritanism, social restrictions and moral repressions of human nature,” but in 1909 the chance of a job on the Age lured him to Melbourne, where he settled in happily for a decade. Then, between 1919 and 1935, when he retired permanently to the farm near Sorell, he switched between freelance writing and journalism, mostly with the Age but also, briefly and unhappily, with the Melbourne Herald in 1927.

A shy man, Bridges did love the companionship of other journalists. Keith Murdoch, future father of Rupert, was one of his early friends on the Age, although they didn’t remain close. There was Neville Ussher, of the Argus and the Age, who died during the first world war and whose photograph Bridges kept close to him for the rest of his life. And then there was Phillip Schuler, son of Frederick Schuler, editor of the Age.

High-spirited, charming, handsome: Phillip Schuler’s nickname was “Peter” because of his Peter Pan personality. Friendship “blossomed” during a bushwalk on a “golden August Sunday at Oakleigh,” then only sparsely settled, and after that the two young men spent many weekends together. They read the same books, roistered in restaurants and theatres, and tried their own hands at writing plays.

On a walking holiday in Tasmania in 1911 the two men tramped from Kangaroo Point (Bellerive, on the eastern side of the Derwent) down to Droughty Point, “the way of many of my boyhood days.” They climbed Mount Wellington to the pinnacle and spent two nights at the Springs Hotel, part way up the mountain (sadly burned to the ground in the 1967 bushfires). From an upper window they watched the “glory of the sunrise,” looking across to Sorell and Frederick Henry Bay. In 1948 Bridges wrote:

The beauty and wonder of the island rolled on me, possessed me, and possesses me yet. We were talking and talking — life, Australia, journalism, literature; always we planned; always we hoped. We were worshipping life, the island, the sun.

If you are thinking what I think you are thinking, then no. Schuler returned Bridges’s friendship, but as his biographer has made clear, Schuler was thoroughly heterosexual and Bridges knew it. This could have been one of those passionate platonic friendships between men, but in 1990 I thought, and I still think, that Bridges was absolutely in love with Schuler.

After brilliant success as the Age’s correspondent during the Gallipoli campaign in 1915, Schuler enlisted for active service but was killed in northern France in June 1917. His last letter to Bridges ended: “Keep remembering.” Schuler’s photograph was another that Bridges cherished always, and indeed he had it reproduced in his 1948 memoir, but Bridges himself was no Peter Pan. He had to carry on facing the disappointments that life inevitably brings, and he was not stoic. In his fifties, living with his sister Hilda back at Woods, he felt the loneliness deeply and became a demanding, querulous, self-pitying man who drank too much.

He did still have many friends though, and in 1938 he began corresponding with Ted Turner, an amateur painter whom he met through their membership of a Melbourne literary society known as the Bread and Cheese Club. Bridges was only a distant member because he rarely left Tasmania by then, but he took a fancy to Turner and found great entertainment in the younger man’s letters, which reminded him of his own Bohemian days in Melbourne. Bridges heaped affection and confidences on Turner, requested a photograph and was delighted with it. He was cross if Turner delayed writing and begged him to visit Tasmania (“Ted old son… I wish I had your friendship — near me!”), but Turner never did.

The two men met only once, in April 1940 when Bridges made the trip to Melbourne, but Bridges went home hungover and with a bout of influenza. He admitted to Turner that the trip had been “a series of indiscretions.” What exactly that meant I couldn’t tell, and their correspondence declined later that year.

Did I indulge in absurd speculation in my thesis about domineering mothers and emasculated fathers? No, but it was impossible to ignore the breakdown of the marriage of Samuel and Laura Bridges, Roy’s parents, in 1907 when Roy was twenty-two. Samuel was pleasure-loving and extravagant, and eventually the house in north Hobart where Roy and his sisters were brought up had to be sold. Of Laura, Samuel apparently said that she “may as well” live with Roy because “it’s plain she’ll never be happy without him.”

Laura managed the household while Hilda became her brother’s amanuensis, writing or typing all his novels from his rapidly scrawled sheets. Roy supported them all financially, although Hilda earned an income as a musician and fiction writer. Only now does it occur to me that there might have been an understanding among the three of them, tacit one would think, that Roy would never marry. Before Laura died in 1925 she begged Hilda, “Whatever happens, look after Roy,” which Hilda did. She never married.

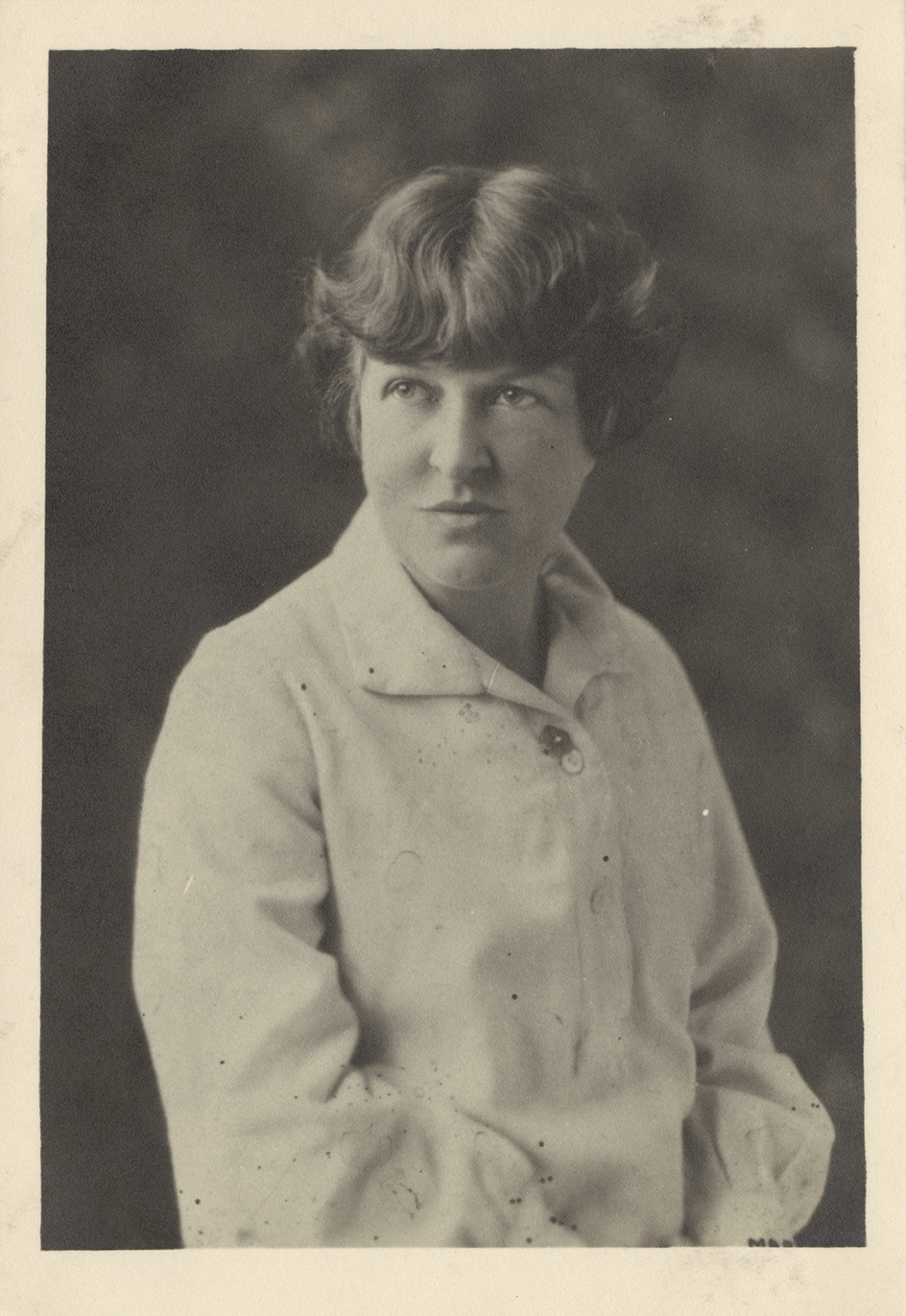

Hilda Bridges, probably in the 1910s. State Library of Victoria

Did I mine Bridges’s writings for autobiographical clues to his sexuality? Yes, for no one warned me against mistaking writers for their characters, and anyway there was so much material to work with. Convicts, bushrangers, and the endeavours of the early colonists to establish a free and democratic society on Van Diemen’s Land: Bridges wrote obsessively on these themes for years.

Novel after novel, especially in his mature period, features a misaligned relationship between a beautiful, passionate woman and an unsuitable man. A son of the relationship will turn up as a convict in Tasmania, and the plot revolves around whether the mother’s folly can be forgiven and her son redeemed by love. Bridges despised hypocrisy and religious intolerance, and his clergyman characters are tormented by unsuitable desires and undone by having to preach Christianity to convicts who are not inherently evil but victims of an unjust society.

Symbolic of society’s condemnation of a convict were the physical scars left by flogging, for which Bridges seemed to have a horrified fascination. In his final novel, The League of the Lord (1950), the Reverend Howard France sits in his study in Sorell picturing an illicit meeting between a beautiful young local girl and her convict lover, which he knew was occurring at that moment. France is jealous of them both. “[Joan’s] eyes are deep blue… her mouth is red, her hands long and white… exquisite…” Further down the page France imagines the couple being caught, which would mean the triangles for young Martin: the “hiss and crack of the lash across strong young shoulders… red weals… red flesh… red running… red.”

Martin is deeply ashamed of being a convict and struggles to accept the love offered by his (free) family in Tasmania. He recalls his journey there on a transport ship, hoarded below decks with hundreds of other convicts:

The faces, the eyes, the voices, the hands; the loathsome, pawing, feeling, gliding, gripping hands… the squeaking laughter in the obscene dark… the foul perverted horde that [had] been men and boys… the brooding, breeding evil, the bestiality, lifelong contamination, incurable, malignant, cancerous.

I underlined this passage in my copy of The League of the Lord but didn’t know how to use it. Now I see it two ways. It could simply be an evocation of Marcus Clarke–inspired Tasmanian gothic. Or it could be evidence that Bridges’s many convict characters are studies of profound shame, self-hatred and alienation. In this reading, those convict characters were versions of himself, their alienation his own, and homosexuality his source of shame. Either interpretation is possible.

Roy and Hilda Bridges’s return to Woods in 1935 fulfilled a promise Bridges had made to their uncle, Valentine Wood, who’d died in 1930, to take on the old place. He knew that Woods meant more to him than Melbourne: “that I was of this land; that it was stronger than I, and that when it willed it would call me back.” Still, brother and sister missed Melbourne terribly, even though overstrain and a nervous dread of noisy neighbours had driven Roy to the brink of a breakdown.

It might have been in these years that the Imperial Hotel incident occurred. Did it? Bridges disliked Hobart, but if it was casual sex he needed, where else could he go? And yet, if the Imperial was a known place for gay men to meet, the police would surely have been there too. Put that way, the incident seems unlikely.

Bridges’s heart condition worsened in the late 1940s and he had a chronic smoker’s cough. He refused to go to Hobart for tests and hated doctors visiting from Sorell. One doctor threatened to have him certified to get him to hospital. “He implied my not liking women about me in such treatment was an abnormality,” Bridges grumbled to a friend. The burden of his care fell as usual on Hilda. Eventually he had to be rushed to hospital in Hobart anyway, and he died there in March 1952 aged sixty-six. Hilda stayed on at Woods for many years until she moved to a Hobart nursing home, where she died in 1971.

I never spoke with Bridges’s family about his possible homosexuality because I was relying on them for recollections and photographs. I drove out to Woods for a final polite visit to give them a copy of the thesis, and after that, unsurprisingly, I never heard from them again.

My research had not included any reading on the ethics of biography so instead I learned it the hard way. I’d gained the trust of my subject’s family only to betray that trust in the end. However, this time — for this essay — I contacted a relative a generation younger and did have an open conversation. There is nothing new to say except that Bridges left a complex personal legacy that is still being felt.

Some people blame homosexuality among male convicts for the long shadow of repression and homophobia in Tasmania that delayed gay law reform until 1997. Perhaps. Such a thing would be hard to prove, and in any case, what is “proof”? What constitutes “evidence” of a queer life? When found, how do we assess its significance? The thing is to not shrink from the task, because with patience and honesty we might still open up some of these painful histories to the light. •