In March this year the Australian War Memorial invited Canberra schoolchildren to name the two massive cranes that will tower for the next two years over the memorial’s building extensions. Visible from space no doubt, the cranes will be named “Duffy,” for one of Simpson’s donkeys, and “Teddy,” after Edward Sheean, Australia’s latest Victoria Cross recipient. “Poppy,” “Anzac” and “Biscuit” were among the names rejected.

The exercise was presumably designed to make Canberrans feel good about the controversial $550 million project. Cranes hovering overhead and massive earthworks front and rear will invite many uneasy glances at a building that has nestled for decades at the foot of Mount Ainslie as if it grew of its own accord out of the ancient earth.

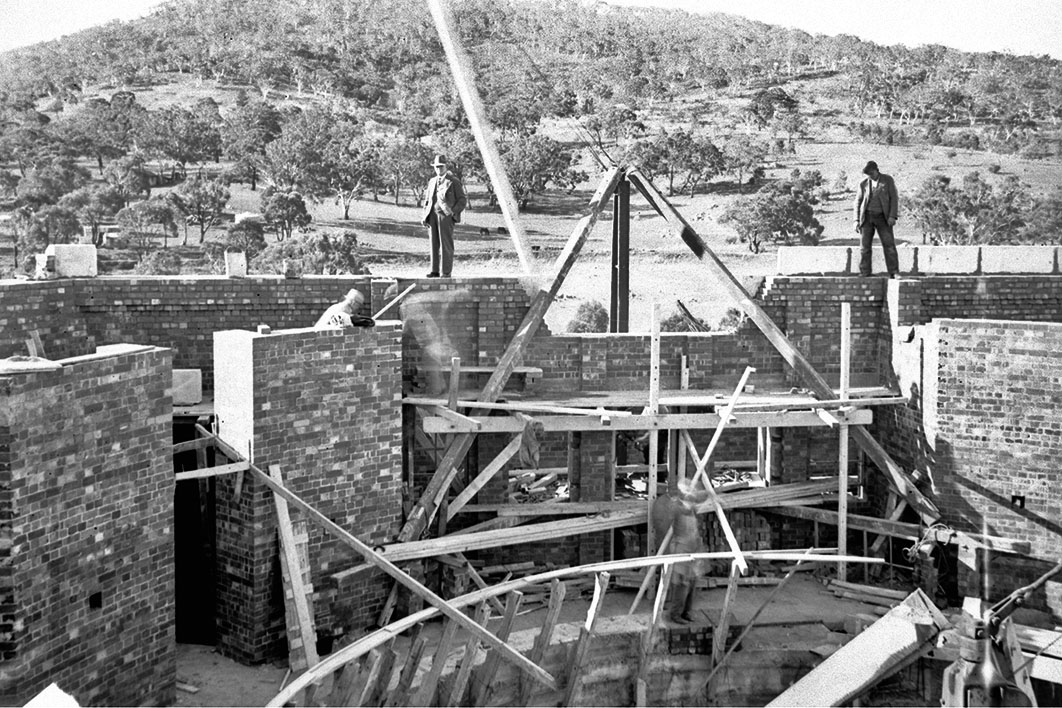

Of course it did not. As Michael McKernan showed in his history of the memorial, Here Is Their Spirit (1991), between the official announcement of the site in 1923 and the opening of the building by prime minister John Curtin in 1941, hurdles and setbacks tested the faith of its most ardent supporters. Even in 1941, the building was incomplete: the exhibition galleries were opened to the public but the grounds and commemorative areas, including the Roll of Honour and the Hall of Memory, took several more decades to finish.

All those struggles might be forgotten, but the project was once regarded with such trepidation by federal authorities that it was held to a budget — £250,000 — that was manifestly inadequate even for the modest, restrained building that Charles Bean, one of the memorial’s founders, had dreamed of. He had imagined a memorial on a hilltop: “still, beautiful, gleaming white and silent.”

Politicians, though, were more interested in memorials in their local districts than a national memorial most of their constituents would never see. After a vexed and abortive architectural competition, a design for the national memorial was agreed upon in 1929, but with the onset of the Depression the project had to be shelved. Finally, in February 1934, the building contract was awarded to Simmie & Co., a firm that built many of Canberra’s early public and commercial buildings.

It’s long been a fancy of mine that the land itself tried to reject the building being raised upon it, calling up malevolent spirits to cast spells over it. For starters, the winter of 1934 was the wettest then on record. Next, the foundations took much longer to excavate than expected because the trial holes dug during the tender period had not revealed how hard and rocky the site really was. Quizzed over delays in the project, Simmie’s principals complained that they had been “grossly misled” in this regard.

The building was declared weathertight and ready for occupation in November 1935, but after all that effort the result — a long, low construction of garish red bricks from the local brickworks — was embarrassingly basic. The beautiful Hawkesbury sandstone cladding that lends so much quiet beauty to the building had not yet been applied, and influential observers complained it looked “squat” and “prison-like.” Building plans were hastily altered to raise the height of the walls, and later the dome, causing more headaches for Simmie.

Despite these inauspicious circumstances, a doughty bunch of about twenty-five staff began preparing to move themselves and their families from Melbourne to the infant capital, along with 770 tons of objects, paintings, photographs, books, archival records and stores. These had been stored and exhibited in leased premises in Sydney and Melbourne.

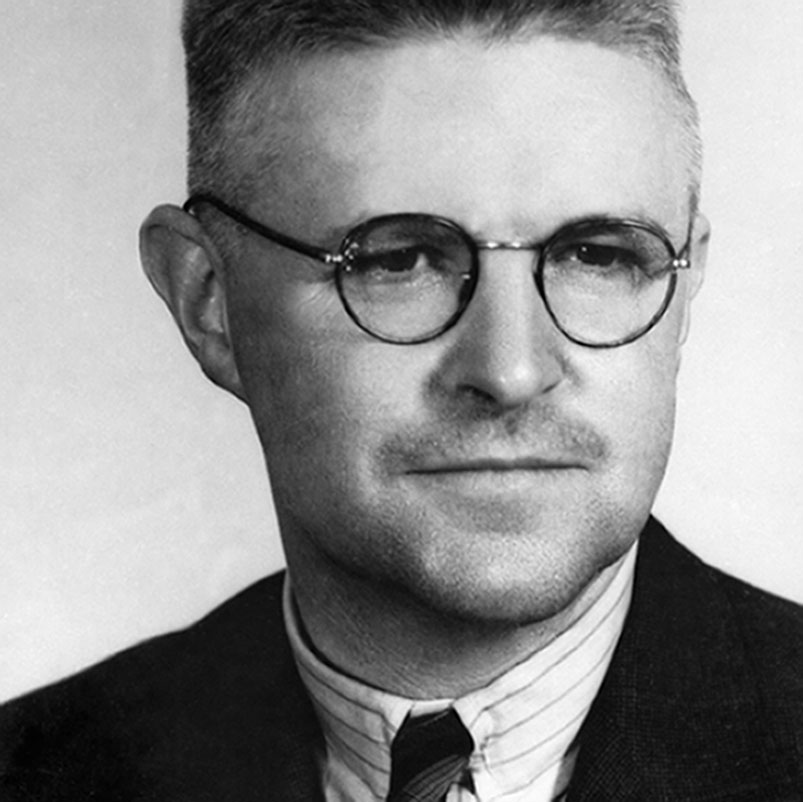

Staff arrived in November 1935. While deputy director Tasman (Tas) Heyes moved into a house provided in Forrest, south of the Molonglo river, director John Treloar made what he called a “private arrangement.” After several previous stints living in Canberra, his wife Clarissa had refused to move this time and remained in Melbourne with their four school-age children. Treloar set himself up in the memorial with his suitcases, a wardrobe and a single stretcher. He was not a man with elaborate personal wants; as a staff clerk on Gallipoli in 1915 Treloar had slept and worked in the same dugout and took advantage of the short commute to work punishing hours. This he now proceeded to do again. Although not a cold or humourless man, austerity suited him.

It had been a wet weekend, and from his house in Forrest late on that Sunday afternoon, 12 January 1936, Tas Heyes was keeping an uneasy eye on the sky. In those near-treeless days you could see far across Canberra, and it was obvious that a storm was gathering over Mount Ainslie. He and Treloar had inspected the memorial building on the previous Friday evening after heavy rain and found water seeping in through an unfaced brick wall on the lower-ground floor where the library would be. Cases of collection material stood nearby, ready for shelving. The water seepage had not been serious then, but now, when Heyes found that the storm had blotted out all sight of the memorial from his home, he got into his car.

In January 1936, just as everyone was settling in, those evil spirits decided as a final gesture to turn on one of Canberra’s cataclysmic summer storms. Today, staff in Canberra’s cultural institutions fully comprehend the power of these events, but in 1936 the memorial’s building was piteously vulnerable and the newly arrived Melburnians quite innocent of the harsh extremes and occasional violence of the weather on the high plains south of the Brindabellas.

John Treloar was already there, of course, along with two watchmen, Thomas Aldridge and George Wells, at their change of shift. Mount Ainslie was the centre of a terrific cloudburst, and from its slopes torrents of water were descending. The stormwater drain on its lower slopes had overflowed and water was washing silt and debris down to Ainslie, Reid and Braddon, and becoming trapped in the excavation around the memorial. The building’s lower-ground floor was below the watercourse and water was advancing into the building, sweeping down passages and up to the cases containing precious war records.

Another war: the AWM’s first director, John Treloar, shown here shortly before his secondment to the military in 1941. Ted Cranstone/Australian War Memorial

Many of the cases were raised from the floor on timber baulks, but this precaution had ceased when the building had been declared weathertight, and now several hundred cases were in immediate danger. The three men on site needed help, but none of the staff at that time had home telephones, so Aldridge drove off to gather them from their homes, leaving Treloar and Wells to scavenge timber to make platforms for the cases.

Scarcely had they begun this task when Aldridge returned, having abandoned his car where it had become bogged even before he got out of the grounds. By now, more water was sweeping into the building across a landing that had been built at a rear entrance to help bring in large objects. Treloar and Aldridge tried to dig a ditch to divert the water, but, as Treloar later reported, “the rocky ground defied the shovels which were the only tools we had.” They tried to wreck the landing but it was too well built.

Leaving his men to struggle with the records cases, Treloar phoned the fire brigade and was told that the chief fire officer could send men to pump water out of the building but only if it reached six inches, and they could not help move records or exhibits. Soon after, the telephone service broke down, leaving the three drenched and desperate men isolated. At this point, Tas Heyes finally made it through.

It was growing dark and the building in its primitive state had hardly any lights. Water was washing under doors and through unfinished sections of the roof. The waste pipes of wash basins and drinking fountains, as Treloar said later, “threw into the air jets of water several feet high.” Water was about to enter the room where the works of art were stored. It was impossible to move the cases in time, and improvised squeegees proved to be hopeless. Using chisels and their bare hands, Treloar and his staff tore up the floorboards at the entrance to the room, and the water, which was now creeping around the edges of the art cases, escaped beneath the building. Heyes set out in his car in another attempt to round up more staff to help; by 8pm about a dozen men were on the site and a few oil lamps had been obtained.

The worst was over. Manholes over drains were opened and water swept into them. Staff continued to clear the building of as much water as was possible, working in the dark with only improvised tools. By 1am Treloar decided to suspend work. The men were exhausted and most had been wet through for hours.

Treloar later told a colleague that the suit he had been wearing that day was ruined, a rare reference to himself and his personal comfort. Where he slept for the rest of that night isn’t known, but Heyes, a friend and colleague for many years, probably took him back to his house. Forrest had received no more than an ordinary shower of rain.

The next day the Canberra Times carried long reports of the flood. Six inches (more than 150 millimetres) of rain had fallen on Civic and the inner north in ninety-five minutes. The paper had rarely had such a dramatic local event to cover.

The memorial’s misfortunes were ignored at first in favour of the dramatic rescue of motorists stranded on Constitution Avenue, the many roads that were scoured or washed away, the five feet of water in the basement of Beauchamp House (a hotel in Acton), the “pitiful” state of Miss Mabbott’s frock shop in Civic, and the washed-out gardens and drowned chickens in Ainslie. These local calamities mattered more than what had happened at the memorial, of which the paper finally gave a brief report the next day. Few people really knew what went on in this strange new building anyway.

Monday 13 January at the memorial was a heavy, depressing day of mopping up, opening hundreds of cases and separating the wet from the dry. Two to three inches of water had entered the building. Some 2648 books were damaged and 719 had to be rebound. Among the most valuable was a large collection of histories of first world war German military units, which Treloar described to a newspaper reporter as “irreplaceable.” More than 700 cases of archival records were damaged, as were 10,327 photographic negatives. Thankfully paintings had been stored on their edges in crates so that only the frames were soiled, but 389 were damaged and 300 had to be remounted.

In the end, the damage was not so bad. The museum objects, stored on the upper floor, were untouched. Some of the damaged records were duplicates and, as Treloar reassured his board of management, water-stained books would not be less valuable as records, and the pictures when remounted would be “as attractive as formerly.”

Prints existed of some of the negatives, and the emulsified surfaces of the negatives had fortunately been fitted with cover glasses to protect them. Most of the records cases had been stored on timber two or three inches above the floor, although Treloar bitterly regretted his decision to abandon this practice shortly before the flood.

The salvage operation was instructive and useful in many ways. Treloar was enormously capable, but he liked to consult experts and tried to keep himself abreast of practices in museums, galleries and libraries in Australia and overseas. Here was a chance to call in some help and renew important associations. Leslie Bowles, a sculptor who often worked with the memorial, travelled from Melbourne to advise on the treatment of some battlefield models affected by the flood. Although Kodak and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research were contacted for advice on the treatment of the negatives, Treloar soon turned to an expert from the Photographic Branch of the Department of Commerce in Melbourne.

The paper items needed the most treatment. A hot-air blower was obtained for the soaked documents, and eight local teenage girls arrived with their mothers’ electric irons on the Thursday after the flood. Treloar had been advised that the best way to fully dry and flatten the documents, newspapers and pages of books was to iron them, presumably with a piece of cloth over the paper. This was to be the job for the next few weeks for Enid, Ivy, Agnes, Betty, Jean, Thelma, Stella and Gwen.

The eight had been recruited through the Canberra YWCA, whose secretary had had many applications for the curious engagement. They were paid under the award for government-employed servants and laundresses, but surely never was a laundress entrusted with such a strange and delicate task. How anxiously Treloar must have watched them go about their work.

Some of the damp documents were part of the memorial’s collection of unit war diaries — not soldiers’ private diaries (although the memorial had a fine collection of those as well) but official records kept by each military unit. For Treloar, they were probably the most important part of the collection and he knew them intimately. They were mostly created on the battlefront, and it would have been agonising to imagine them engulfed by muddy water in the very building created to house and protect them.

Support and commiserations poured in. Arthur Bazley, assistant to official historian Charles Bean, phoned Treloar from Sydney to offer any help he could, using his Sydney contacts. Bean, on holiday in Austinmer, wrote to Treloar that he and Heyes “must have this comfort, that you know that all concerned are so aware of your carefulness and forethought, that their only feeling will be one of sympathy.” Federal interior minister Thomas Paterson, who had responsibility for the memorial, telephoned to find Treloar still lamenting the cases stacked directly on the floor; “an officer could not expect to be a prophet” was his kindly advice to the director.

After all the years of work and worry, Treloar was not present at the opening of the memorial on Armistice Day, 1941. He was in uniform again, based in Cairo managing the collecting effort for yet another war, leaving Tas Heyes to organise the ceremony.

The first Anzac Day at the memorial was held in 1942, the national ceremony having previously been held at Parliament House. With so many Australians fighting abroad and with the enemy at the nation’s doorstep, Anzac Day in the nation’s capital had never been so sombre (and wouldn’t be again until 2020, when Covid-19 restrictions forced the cancellation of traditional commemorations).

No veterans’ march was held that year, and Anzac Day sports were cancelled. The Canberra Times editorialised that the day found Australia a “battle station.” Anzacs “now stood guard on their own land” and any honour owed them was never so much due as on that day. It was to be a day “not of works but abiding faith.”

At the memorial a twenty-minute ceremony held in the commemorative courtyard was attended by a mere 600 people. Around them were bare walls: no Roll of Honour yet, and an empty Hall of Memorial. A single aircraft flew low overhead. Weatherwise, the morning was cool and overcast but there was no rain. •