The problem with conspiracy theories in Italy is that they can sound so plausible and reassuring — unlike the truth, which tends to be messy, distasteful and often unbelievable.

The Moro affair is a good example. In March 1978, the former Italian prime minister and man most likely to become the next president, Aldo Moro, was kidnapped by the Red Brigades, a far-left terrorist group, in an attack that left five bodyguards dead. After fifty-five days, Moro was assassinated and his body left in the boot of a red Renault 4 parked near the headquarters of both the Christian Democrats and its rival Italian Communist Party.

The Red Brigades had good reason to want him out of the picture. As chairman of the Christian Democrats he had been chipping away at what became known as the compromesso storico — the historic compromise that would have brought the communists into something like a government of national unity. It would have been a globally significant feat: for the first time European communism would have been locked into the democratic process rather than brooding on the fringes of political discourse as the menacing bridgehead of Soviet-style authoritarianism.

But the Red Brigades were a revolutionary movement and anything short of the complete destruction of the regime was unacceptable. Then again, they weren’t alone in opposing the compromise. The Italian Socialist Party argued against it, and so did smaller centrist parties. The right wing of the Christian Democrats was concerned about the ideological impact of wedding the party to the secular and democratically dubious communists. As for the Americans — they hated the idea.

This is where Italy’s penchant for dietrologia — the study of what lies behind surface events — kicks in. There’s no doubting the Red Brigades carried out the kidnapping and assassination. But who else wanted Moro dead? Could authorities have done more to free him?

Once you add to the mix the names of the two Machiavellian Christian Democrats who managed the crisis — prime minister Giulio Andreotti and interior minister Francesco Cossiga — the speculation escalates. Did they stand to benefit from Moro’s assassination and its likely scuttling of the compromise? And where, inevitably, was the CIA in all of this?

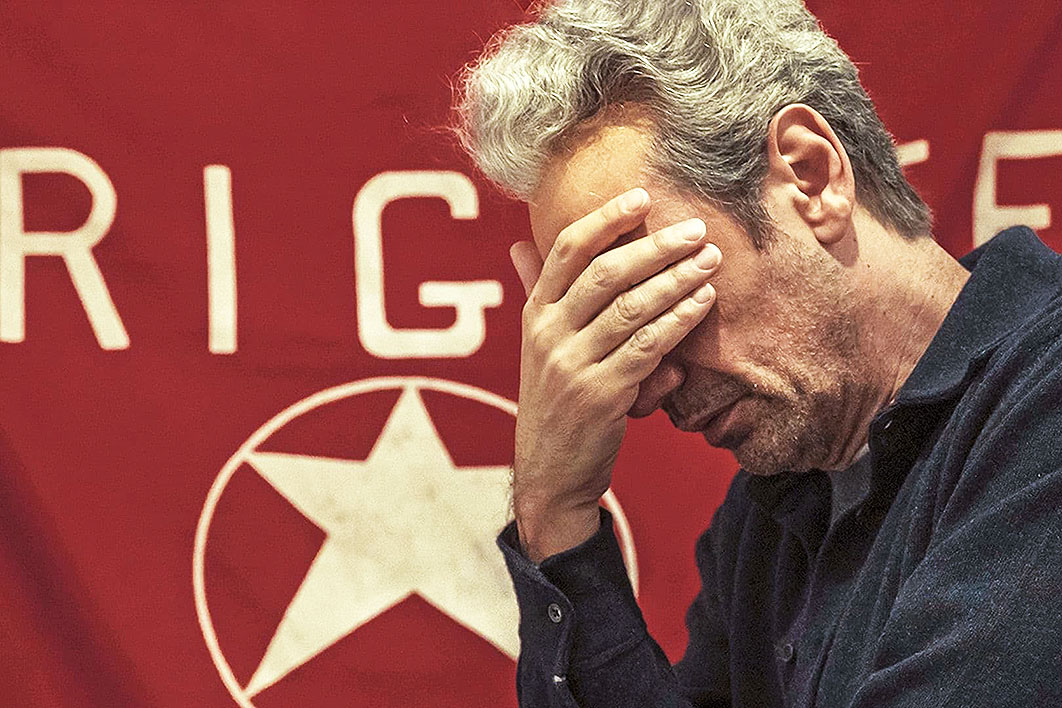

Marco Bellocchio’s thrilling series Exterior Night, now streaming on SBS, flirts with many of those conspiracy theories. There’s the sunglasses-wearing American secret service agent who offers Cossiga bad advice on how to bring Moro home alive, and there’s the inscrutable Andreotti, whose impassive response to the Moro family’s pleas that he negotiate with the terrorists offers a nod and a wink to those who believe the true story of the kidnapping has yet to be told.

Ultimately, though, the series comes down on the side of the more reputable historical account of the fifty-five days in which Italian democracy appeared to be hanging by a thread. Of course the Italian government could have done more to secure Moro’s freedom — but that doesn’t mean it should have.

Both Andreotti and Cossiga were reportedly distraught by the decisions they were making, yet they appeared to understand that negotiating with terrorists at a time of crisis, or any attempt to find a middle ground with people who wanted to overturn democratic institutions, wasn’t an option. The damage to the Italian state would have been irreparable. Even the Communist Party came out against cutting a deal.

Moro’s family came to understand that their adored husband, father and grandparent had become the sacrificial lamb and were understandably outraged; the Exterior Night episode focusing on Moro’s wife Eleonora Chiavarelli, played by actress Margherita Buy, is one of the most moving of the series. The realisation that her husband’s political friends and allies weren’t prepared to do everything necessary to get him back is gradual and ultimately heartbreaking. The increasingly strident pleas for help from Moro, whom the terrorists encouraged to write to his colleagues, ended up sealing his fate. The prisoner was asking for the impossible: an accommodation was out of the question.

As television, Exterior Night is far from perfect. Some of the politicians come across as caricatures: Andreotti, with his hunched back and thick-rimmed glasses, hovering around with his trademark lack of empathy; Cossiga’s ostentatious Sardinian accent and his misplaced trust in the security charlatans who listen in to thousands of phone conversations without gaining a shred of insight into the terrorists’ operations.

But there’s plenty Bellocchio does get right, including his portrayal of a country ravaged by political violence from both the far right and the far left. I arrived there at the end of 1978 and what’s on the screen looks all too familiar — the machine-gun wielding officers and soldiers, the blood-stained Alfa Romeo police cars on the evening news, and the terrifying, violent graffiti sprayed onto the walls. (The vandals often spelt Cossiga with a “K” and two “SS” symbols — suggesting some kind of continuity with Nazi Germany.)

It’s hard to describe life in a country that had endured ten years of brutal terrorism. It wasn’t just the fear of physical violence; it was the very real concern that institutions would collapse — that the terrorists would win. Italian democracy was fighting for its survival. The image of Moro in captivity, holding up a newspaper with the five-pointed star of the Red Brigades behind him, was horrifying not just because of what it meant for the hostage but also for the impact it was having on the country.

In the midst of the turmoil, Italy’s silent majority was fatigued but also ready to be inspired by acts of bravery in the face of intimidation. The names of Moro’s five bodyguards — two members of the Carabinieri, the force that reports to the Ministry of Defence, and three policemen — were published and venerated, and when the prosecutors and investigators ultimately brought the fifteen members of the Red Brigades to account they helped restore at least some faith in the justice system. As Italy moved into the 1980s it became clear that Moro’s assassination had been the high-water mark of the “years of lead” and that Italian democracy, with all of its flaws, had won its fight against extremism.

Yet the enduring divisiveness of the Moro affair means any attempt to tell the story is bound to face scrutiny. Bellocchio is a filmmaker of the communist left — a fact that wouldn’t be lost on Italian viewers. Some would argue that the filmmaker has humanised a pack of cold-blooded assassins by giving the terrorists their own chapter in the story and attempting to define their motives.

But how could it have been otherwise? It’s hard to know how the terrorists could be depicted without the viewer being reminded of how relatably Italian they were. From the places where they live, the words they utter, the food they prepare for both themselves and the hostage, their petty obsessions about being taken seriously, their denied but undeniably bourgeois social backgrounds — Bellocchio’s terrorists emerge as the embodiment of the very country they want to undermine.

Indeed, the untold story of the tragedy is how petulant the terrorists were — something Moro appeared to allude to in the more than fifty letters his captors allowed him to write. The Christian Democrats bristled at the tone of Moro’s letters — the undignified pleading, the insistence that the Italian government negotiate for his release. But Moro was playing for time; he knew that for as long as he could produce content that dignified his captors by presenting them as worthy interlocutors for the Italian state he would be worth more to them alive than dead.

The more the hostage crisis went on, though, the firmer the resolve of both the Christian Democrats and the Communist Party not to negotiate. (The Italian Socialist Party, oddly, became the party of flexibility, urging the government to embrace a “humanitarian” approach.) In that sense, Moro’s family was right to conclude that Andreotti and the government had given up on the former prime minister. But that’s a far cry from suggesting the Red Brigades were merely pawns of Christian Democrats who had somehow outsourced the elimination of a common foe. As brutal as the terrorists may have been, there can be no doubting they were ideologically driven and the Christian Democrats topped the list of their enemies.

But there’s an even more convincing explanation for Moro’s ultimate assassination: the rampant incompetence of Italy’s law-enforcement and intelligence agencies. Bellocchio alludes to it, pointing to Cossiga’s exasperation with the intelligence he was receiving from his top brass. But the filmmaker barely scratches the surface of the mistakes made before and during the violent kidnapping in Rome’s Via Fani on 16 March 1978. To do so would have required another ten episodes.

The Sicilian writer Leonardo Sciascia first examined the Moro assassination in his 1979 essay L’affaire Moro; he later became a member of parliament and was on the committee that investigated both the kidnapping and the failings in policing. His dissenting minority report, which is included in recent editions of the essay, was breathtaking in its account of how those whose job was to keep Italy safe messed up at almost every turn. The failings are too many to recount in full, but a few of them stand out.

The particularly determined carabiniere who headed Moro’s detail, Oreste Leonardi, reported before the abduction that he had been followed, and warned this might indicate a kidnapping was planned. He was particularly concerned by a suspicion that Moro was being closely monitored at the university where, as a professor of law, he lectured. This information dovetailed with the intelligence available to the government at the time, suggesting the Red Brigades had indeed been planning to target a key member of the Christian Democrats.

But Leonardi’s warnings went unheeded: Moro continued to travel in an unarmoured car; and his underequipped and inadequately trained bodyguards continued, fatally, to use the same routes to move around Rome.

Once the kidnapping had occurred, the police operation was clumsy and driven by public opinion. Initial intelligence had identified a printer in Rome used by the terrorists, but the manpower required to place both the printer and other key associates of the Red Brigades under surveillance never materialised. Instead, law-enforcement agencies engaged in what a senior policeman would describe as “parade operations,” with more than 4000 agents mounting roadblocks and carrying out raids that yielded no actionable intelligence.

The one piece of information the police did have, the word “Gradoli,” was dismissed after a cursory glance at a street directory. They concluded there was no street by that name and started to examine a small mountain town called Gradoli. They were wrong — Moro was being held in Rome, at number 96 in the very real Via Gradoli.

Even more astounding was the reluctance to parse Moro’s letters for hints of where he could be found. What became clear when the parliamentary committee examined the correspondence years later was that Moro was outsmarting his Red Brigades censors and continued to provide hints right up until his mock trial by the “people’s tribunal” and his subsequent execution. First, he offered repeated hints that he was still in Rome — his use of the word qui — “here” — was strategic. One sentence Sciascia highlights — mi trovo sotto dominio pieno ed incontrollato (I find myself in a complete and uncontrolled domain) — must have been interpreted by the terrorists as an unusually poetic and illogical reference to his inner turmoil. Even a modicum of lateral thinking could have understood it as “I’m in a condominium that has yet to be checked by police.”

But Sciascia’s version of events, based on hours of hearings, would make for grim viewing; it’s also less palatable than the many conspiracy theories (most of them debunked by the parliamentary review) that are still out there.

None of this should stop us from considering the counterfactual: what would have happened had Moro survived and the historic compromise succeeded? There’s an argument to be made that not much would have changed — by the time the Berlin Wall came down, the Italian Communist Party had already begun to transition towards Europe and democracy. Whether having the Communists inside government for the last years of the “First Republic” would have altered the course of history is difficult to determine.

Instead, the wounds of the Moro affair remain open and, as Bellocchio’s TV series suggests, its handling continues to divide the country. The graffiti of the late 1970s and early 1980s, including the ubiquitous Cossiga boia (Cossiga executioner), have long gone; the memory of those dark, terrifying days will remain with Italians for years to come. •