AI photography — we’ll leave aside for a moment the question of whether “photography” is the right word — has arrived with a rush. Along with it has come a burst of commentary, some welcoming its vast artistic potential, some warning of its capacity to render individual creativity redundant. What has been obscured in all the excitement is how the undoubtedly revolutionary aspects of the new AI tools also manage to coexist with and build on the history of photography.

When the winning entry in a small Australian photo competition was revealed as “fake” earlier this year, there was much debate over whether technology was taking over from people. What purported to be a drone photo of a beach had been generated using AI. Not long after, followers of another photographer’s Instagram account were dismayed when he revealed he had used AI to create images.

Some react angrily to revelations like these, expressing outrage at a fake photo masquerading as real; others claim that its fakeness was always obvious. The waves are going in the wrong direction, as more than one person said of the beach photo. “If you know what to look for, you can spot these fakes at a single glance,” say the founders of the website Which Face Is Real? (“For the time being,” they add.)

Given that photographic experimentation and manipulation dates back to the very beginnings of the medium, it is hard to understand why this kind of stunt generates such dismay. The cry from doubters over the direction AI is taking us in overlooks the fact that judging the realness of an image has never been straightforward.

Ambiguity over authorship has been part of the world of photography since the beginning, with anonymity and attribution coexisting for the most part comfortably. That world contains works by professional photographers, some of them with stratospheric reputations, alongside “found images” made by amateurs and unknowns, quite possibly created by accident and involving the very minimum of human agency.

The success of a photographic image, its ability to strike a chord in the viewer, has never depended on its place on the spectrum of authorship. We might seek out further images by a photographer we admire because experience tells us that it will be likely to work its magic on us. But we can equally value images whose provenance we will never know.

Such has been the proliferation of photographic images in the digital, “pre-AI era” — that is, up until yesterday — that we are already well attuned to the difficulty of keeping up with the images themselves, not to say with who made what. Anonymous images blend with attributed ones, and if individual images stand out from the crowd we don’t always understand why.

A significant number of practitioners in these early days of AI photography are dealing with this complicated relationship by using handles rather than names. “What led you to choose anonymity,” a Vogue Italia interviewer asks Str4ngThing, an “AI artist of fashion,” to which the answer is “to leave room for interpretation.” This is a neat device for having it both ways — allowing the image to speak for itself while being credited at one remove with whatever success and approbation it may enjoy.

Approbation as a photographer was already running up against the fact that it has become increasingly difficult for an image to stand out not only because there are so many of them, but also because so many closely resemble one another. It has long been the case that certain themes have their moment, with photographers coalescing around those themes — portraiture with the face obscured in some way, photographic re-enactments of the old masters, moody shots of abandoned buildings.

The popular Instagram account, Insta Repeat, has great fun pointing out the unoriginal nature of so much photography, not only by displaying clusters of sunsets and waterfalls, but also by showing how specific subjects — the photographer’s feet dangling over a precipitous cliff, for example — are suddenly everywhere.

Yet all those sunsets also point, in an exaggerated way perhaps, to one of the more attractive aspects of photography as a creative art — its ability to foster collaboration and cross fertilisation, and to encourage emulation. Just as copying the old masters is a way of building painterly skills and confidence, so is making yet another image of a sunset or a girl with a pearl earring a means of mastering the capacities of the photographic medium.

AI is the beneficiary of this profusion. By mining the online datasets, image generation tools such as Midjourney and DALL-E and Stable Diffusion draw on untold numbers of extant, humanly created images, out of which new, AI-generated images are built.

According to Jaron Lanier, among the most illuminating chroniclers of the technological age, these tools “mash up work done by human minds… illuminating concordances between human creations.” Crucially, they are facilitators rather than independent creators. They are not in themselves new minds, Lanier says with confidence.

The philosopher and neuroscientist Raphaël Millière similarly emphasises the primacy of human artistic creativity in the face of this current whirlwind of technological advancement. The nature of artistic creation will change, he says, as it has often changed in the past, but the artist will remain in control.

The key to this artistic control lies in the text, the “prompts” used to instruct the program to produce an image. “This means that visual artists can now craft their art with words, much like poets,” says Millière, forming “a new bridge between linguistic and visual forms of artistic expression.”

The French filmmaker and artist Alain Astruc posts similarly stimulating reflections on the nature of AI image-making on his Substack. He is pleased to discover through his explorations of the new tools what he calls “a certain poetry of the prompt.” Astruc sees prompting as being both an art in itself and a new and exciting means of image creation. It is no surprise, given the power of the prompt, that instructional guides to effective prompting now abound on the internet, following on from the legions of tips on how to get the best out of your photo-editing software.

It is not only emerging young practitioners who are embracing AI. Hailing from an earlier, post-war generation, American photographer Laurie Simmons is well known for her innovative practice, and in particular for her staged scenes of domesticity involving carefully placed dolls and dummies. These images, borderline cute in a deeply unsettling way, have a distinctly proto-AI look to them.

Simmons has recently moved, by her own account quite seamlessly, into exploring the capabilities of AI. The tools can produce unexpected and even unwelcome results, but this only encourages greater deliberation and thought in her choice of prompts. “I feel like an AI whisperer,” she has said.

But perhaps a certain amount of wishful thinking is going on here. Judging by the prompt sequences AI explorers share online, few if any are raising the bar of poetic expression. Nevertheless, the sentiment expressed by Millière, Astruc and Simmons rings true: there is something essentially poetic about the art of prompting, of playing with words to produce the most satisfying result.

It is far too early to tell whether these various expressions of optimism are well founded. The question remains, do the various tools for AI image generation genuinely foster creativity, or do they stifle it? So much is being produced, so much experimentation and playing around is going on, that nobody quite knows.

A further, even more difficult question is whether these images are any good. Do they strike a chord? The critical vocabulary for assessing photography, never very robust, is at a loss when it comes to AI images. The standard online response to an individual AI image is along the lines of “impressive,” “wow” or “ground-breaking,” and from there the eye moves on in an instant.

The only meaningful form of validation so far comes from the collector, occasionally a museum but more often an individual, someone who is “comfortable in the space” and confident enough to pick an NFT image or two from the latest collection, transfer however many Ethereum in payment, and wait patiently to see if their investment pays off — in financial gain, growth of the artist’s reputation, or both.

In that sense, old-fashioned connoisseurship is back with a vengeance. The collector’s eye has become at least as important as the photographer’s in ensuring the continuing life of the image.

This leaves photography seemingly poised between the past and the future, but this is nothing new. Photography has always embodied the transitional state. Even the most “realistic” photograph captures an unrealistic stillness, an artificially stopped moment between the past and the future.

The New York activist photographer and filmmaker of the 1980s, David Wojnarowicz, in his memoir Close to the Knives (1991), suggests that this affinity with transitional states is what drives him as a photographer. “I hate arriving at a destination. If I could figure out a way to remain forever in transition, in the disconnected and unfamiliar, I could remain in a state of perpetual freedom.”

In our current cultural climate, where we are especially fascinated by states of transition — with the spaces between fixed identities, between points of departure and points of arrival — it is not surprising that AI photography should be so heavily preoccupied with the “disconnected and unfamiliar.” Images produced with the aid of AI typically dodge questions of origins and destinations, mixing up the past and the future in a single frame, so that we have little sense of beginnings and endings.

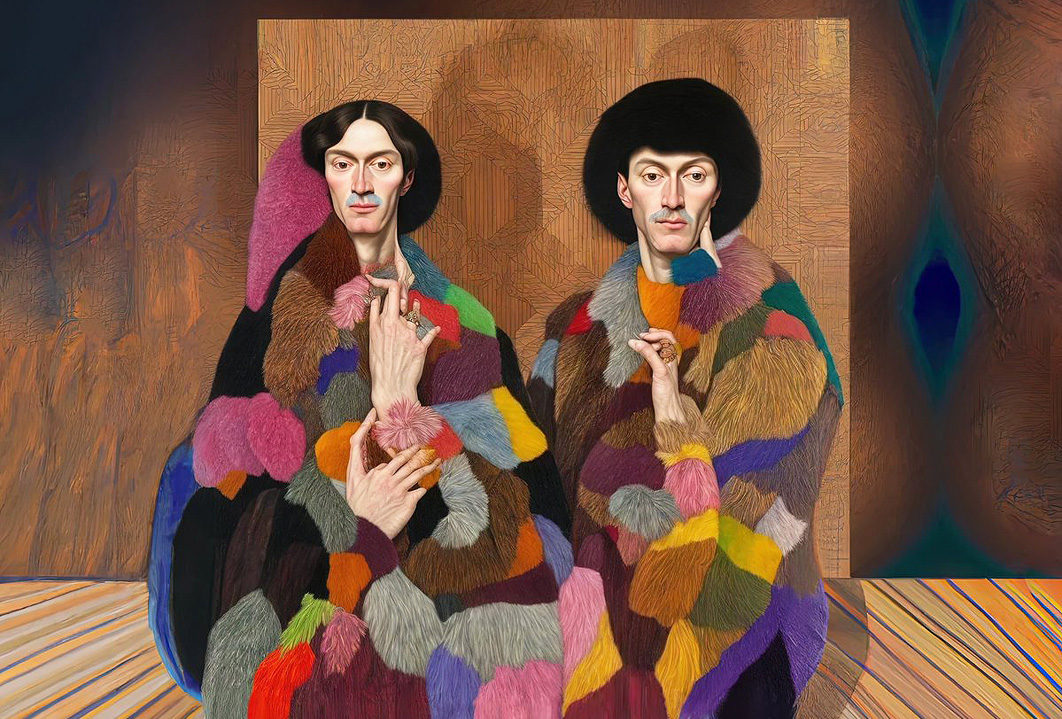

When a human-like figure appears in the frame, they will often have a lost or bewildered expression, as if they don’t quite know what they are doing there or where they have come from. The Canberra-based artist Lilyillo, who describes herself as “collaborating” with AI, places her mock-human subjects in ways that parody conventional studio portraiture, covering them in bright harlequinesque patterns and giving them dreamy, spaced-out expressions, as though they have dressed themselves up and have nowhere to go.

Her images — and those of many other AI artists — suggest that whoever came up with the name of Midjourney for the popular image-generation tool was on to something. Either that, or it constitutes an outstanding instance of nominative determinism. For the great majority of AI images do indeed occupy a middle space, blending past and imagined future by means of a kind of retro-futurism, in which recognizable if distorted figures are placed within fantastical, quirky or off-kilter settings.

The result is unsettling, or “uncanny,” to use the most frequently deployed descriptor for this effect. Freudian notions of uncanniness have long been associated with photography and many past practitioners have deliberately sought to explore and highlight this effect. But the overwhelming emphasis of AI image making on this quality of strangeness is something new.

According to the online platform Fellowship, which displays curated examples of AI photography, “much of the ethos of AI work we have seen so far,” its visual language, can be summed up in the words “uncanny, surreal, fantasy and otherworldliness.” In other words, they’re not real.

Instead, AI helps the artist to create “complex, uncanny, neo-surreal images that can shift artistic styles seamlessly,” says Jess Mac, whose work (including this image) appears in Fellowship’s first group show of emerging AI artists, posted online in April. “This allows for a queering of the imagery,” they say, “undoing normative representations of gender, kinship, and embodiment with ease.” Alain Astruc’s forthcoming exhibition (which might well include these images), to be held in June in Cahors in southern France, has as its title “In the Valley of the Strange,” which is perfectly on point.

Taken as a whole, across the range of AI image production, this preoccupation with uncanniness can feel suffocating. It seems paradoxical that a technology that promises so much creativity and variety can produce so much sameness of approach, but that could fairly be said of the camera too — think of all those sunsets. The capacity for repetition and sameness has never precluded the emergence and the recognition of images that stand out and that strike a spark in the viewer, and something similar will increasingly happen with AI photography.

In contrast to the dispiriting idea that the exciting times, photographically speaking, are over, that all the good photographs have been taken — that the golden age of mid-century photography isn’t coming back — the advocates for AI as an image-making tool have launched a counter-narrative, in which the creation of “photographic” images is being reinvented and re-energised.

Like it or not, the term AI photography is doubtless here to say, even as some persuasively maintain that it’s not photography at all — that it would be more accurately if less sharply described as photography-like. Some favour the term “synthography” on impeccably logical grounds, but it has a bit of a robot-generated ring to it and is unlikely to catch on. AI photography could also be described as AI illustration, in that it is the rendering of text as image, but that hardly sounds cutting-edge.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of AI imaging, at least in the department of cultural change, is its dependence on words. We are even told that tools will soon become widely available that link directly to our thoughts. We will be able to think an image, which others will then view and perhaps admire.

But for the moment it is words, or prompts, that deliver the picture, by means of a technical miracle that most of us can barely comprehend. Just as we have long been familiar with the idea that every picture tells a story, so we will soon unquestioningly absorb this new iteration of the relationship between word and image, in which every story tells a picture. •