A few months ago Inside Story asked me to review The West: A New History of an Old Idea, the latest book by historian Naoíse Mac Sweeney. It might have “a little extra resonance in Australia” at this time, editor Peter Browne suggested. Shortly afterwards, my professional life imploded.

I found myself among the forty-one academics suddenly “disestablished” from their continuing positions at the Australian Catholic University in the name of creating a “more agile and sustainable” education environment. I was then invited to compete in a Hunger Games for fourteen replacement positions. As one of the senior historians among the targeted, more privileged than several others, I have absolutely no intention of doing so.

It’s been an interesting, and unexpected, context for my reading of Mac Sweeney’s brilliant book on the history of the idea of Western civilisation. Back in August I thought I might consider it from the position of one of the few universities in Australia to have recently invested in those disciplines most strongly associated with the West — history, philosophy, religious studies, literary studies and political theory.

Where other universities have been trimming or at least following a course of “natural attrition” when it comes to these subjects, ACU pursued over the last few years a deliberate push to elevate its profile in what is also often called the humanities. The university systematically hired humanities researchers from around the nation and world at senior, middle and junior levels.

In 2020, ACU also became the third and final university in Australia to partner with the private Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation, with which it now runs a Bachelor of Arts program in “the great books, art, thought and practices” that have shaped the West. This program remains largely segregated from both ACU’s regular BA offerings and its humanities research institutes.

In the face of a baffling and partial reversal, however — a reversal that slashes most of its recent research hires but leaves the Ramsay program intact — I now read Mac Sweeney’s book as one of the ousted, a living effect of the extreme tenuousness of the hold of the idea of “Western civilisation” in Australian society.

Tenuousness, in fact, is Mac Sweeney’s primary point. Her central argument is that our modern notion of Western civilisation is not only much newer than we thought but also unstable, compromised, frequently incoherent and indeed “factually wrong.” That notion, briefly, is that Western civilisation emerged from a shared Graeco-Roman antiquity that melded with the rise of European Christendom and led to the Renaissance, the scientific revolution and the Enlightenment, in the process giving birth to liberal capitalist modernity. All these developments occurred on an ever-westward sweep from southern Europe to North America.

Mac Sweeney’s secondary point, pursued more subtly throughout, is that grand narratives of the West have always been used ideologically to justify political ends, either for or against its central claims.

Such a twofold argument might suggest a book that covers only the span of time in which Mac Sweeney reckons our current notion of Western civilisation has been brandished — roughly from the late seventeenth century to the present day. But The West traverses all the ages currently understood to fall within the narrative, starting with the fifth-century BCE Anatolian thinker Herodotus. In fact, more than half the book is dedicated to the pre-seventeenth-century world. The subtitle should more accurately, though surely less cutely, have been “A New History of a Newish Idea, With a Good Chunk of Its Prehistory.”

Mac Sweeney was aware from the outset that her rather abstract subject matter could “easily get stuck in the realms of the theoretical.” To avoid this, she explores her ideas via fourteen lives, each with his or her own chapter. A couple are expected: Herodotus himself, as well as the English Tudor polymath Francis Bacon. The others are mostly surprises, including the Islamic philosopher Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq al-Kindī, the Ottoman Sultan-Mother Safiye and Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam.

All up, Mac Sweeney’s fourteen lives comprise two Anatolians, two Romans, two Britons, two Africans, a German, a Baghdadi, an Albanian, an American, a Palestinian and a Hong Konger. There are eight men to six women. Around two-thirds are scholars of some description; about half of them are significant political rulers.

The book’s biographical method and its vivacious and direct writing style are among its best features, turning Mac Sweeney’s compelling ideas into an enticing, delightful and sustaining read. But not all the figures do the same work. Some are discussed as presumed contributors to the Western tradition while others exemplify its contrary aspects.

The starting line-up shows these two modes neatly. Herodotus, in chapter one, has long been thought an original contributor to the Western tradition, inaugurating the binarism at its heart between “us” and “them” with his depiction of Greek heroes and barbarian enemies. Mac Sweeney insists, though, that Herodotus invoked this binarism solely to undermine it. He was repelled by the increasingly xenophobic triumphalism of his contemporary Athens, writing instead a history that showed equivalent heterogenous societies in all the regions of his known world. He eventually abandoned Athens in disgust at its invention of a singular, superior Greek culture.

Chapter two’s character, meanwhile, the Roman powerbroker Livilla, represents the people who are usually considered the inheritors of Greek culture, the Romans of the first century CE. Livilla’s turbulent life adds great colour but its pertinent part concerns how much Livilla — granddaughter of Augustus — nodded to “Asian Troy” as her most important heartland. Her Rome was an empire born of Trojan refugees and powered by absorbing every set of people within reach. It had no understanding of itself as being oriented towards Europe over Asia, and especially not to the conquered Hellenes.

Baghdadi al-Kindī demonstrates how much the Byzantine empire of the ninth century engaged with the Greek and Roman philosophers of the past. In fact, Mac Sweeney holds that the Byzantines took the thought of the varied ancients more seriously than did anyone in this era, proving that Greek and Roman influence did not “flow in a single channel” to western Europe but instead “sprayed rather chaotically in all directions.”

Godfrey of Viterbo and Laskaris of Albania both feature as warnings of how uncomfortable was the blending of medieval Christendom into Greek, Roman or Byzantine history. They similarly refute any sense of a single flowing channel: the retrofitting of Christian theology into pre-Christian traditions was awkward, painful and sometimes frankly denied.

Chapters six to eight traverse a long Renaissance, showing how this era “stitched together… the uneasy hybrid we now call ‘Greco-Roman antiquity.’” Even so, the Roman writer Tullia D’Aragona shows that there remained much respect in the sixteenth century for the traditions of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Ethiopia. So, too, Safiye Sultan shows that the attraction of the east for many Protestant Europeans was often greater than was an increasingly papalised West. And Francis Bacon exemplifies how emerging scientists, though they learned much from ancient texts, remained wary of any attempt to dictate how or what to think.

American revolutionary Joseph Warren brings the reader finally to the birth of the modern idea of Western civilisation, a truncated version that burgeoned through the prior two centuries but was, we now know, almost incomprehensible to thinkers of earlier ages. Mac Sweeney argues that the idea finally became “mainstream” as a helpmate to the success of the American Revolution. American-tinctured Western civilisation not only instantiated the idea that the West came from a fused and exclusive tradition of Greek and Roman practices, but also implied that those living on the latest western frontier — Americans — perfected the Christian, scientific and liberal threads that adhered seamlessly to the tradition along the way.

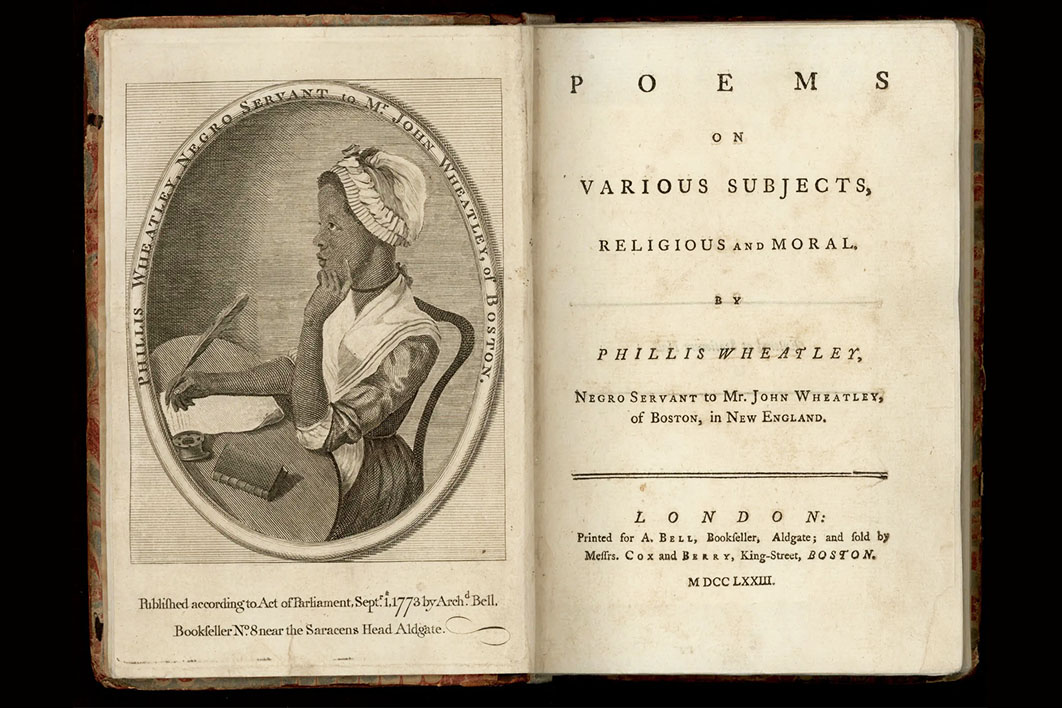

Chapters on the Angolan Queen Njinga and the West African poet Phillis Wheatley provide searing counterpoints, highlighting the ever-sharpening racial exclusions embedded in the modern idea of Western civilisation.

Perhaps the most contentious of Mac Sweeney’s biographical choices come in the final three chapters, where British prime minister William Gladstone, Palestinian critic Edward Said and Hong Kong premier Carrie Lam stand in for the last 200 years. Those who support the extreme tendency to favour the recent past in historical studies will protest that too much is missed, especially the cold war version of Western civilisation: the Plato-to-NATO narrative that focused so intensely on capitalism and founded so many “Western Civ” university courses around the Western world. As a former member of a “Not the Twentieth Century” reading group, however, I am happy to accept the author’s brevity here.

Gladstone represents the West’s zenith, when the idea bolstered a Western bloc that was also dominating the world. Said represents how the West started to come apart via its own critical methods during the twentieth century. And Lam, intriguingly, is a conduit to the challenges the West now faces from without — from a militant Islamic State, from post-Soviet Russia, and most of all from a soaring China.

Mac Sweeney spends less time on her second theme, the ideological weaponisation of the idea of the West, though it is implied throughout. She is clearest on how Warren and Gladstone wielded the idea to justify the rise to “domination” of Euro-American norms. She suggests that it’s less powerful today, when “most people in the modern West no longer want an origin myth that serves to support racial oppression or imperial hegemony.”

I’m not so sure. Advocates don’t have to carry placards of Donald Trump as a gladiator to reveal a desire to perpetuate certain conventions about Western primacy, exceptionalism and natural linearity.

The fact that Mac Sweeney wrote this book suggests she, too, may realise the idea still has dangerous legs. One of her implied points could well be that while the West wreaked plenty of havoc (dispossession, slavery, colonisation) between 1776 and 2001, it may inflict even more damage when brandished in a fractured, unmoored and uneven manner as it is today.

Most importantly, her book is not a call to cancel the study of what apparently constituted the West. Instead, she contends that by investigating the very tenuousness of its claims we can come to see more than just falsity. We get the chance to discover a richer and more diverse global past than we previously knew.

In endeavouring to trace the genealogy of the West back through liberalism, rationalism, Christianity, Rome and Greece, we will find a kaleidoscope of ingenuity, creativity, contradiction and interconnected collaboration in place of a neat arrow. Together, these complexities point to something far closer to universal humanity than was ever imagined in any Western narrative. They should inspire us to move beyond the binary of the West versus the Non-West that yet inflects much modern thinking.

I have no idea if the Ramsay programs currently being unrolled in Australia present the history of Western civilisation in Mac Sweeney’s critical and expansive way. What I do know is that the possibility of studying the politics, religion, literature and theories of the world in which the West arose is now significantly foreclosed at my university. Many regular students, and scholars, will have to turn elsewhere to continue to discover and to explain the ideas that have shaped all our lives. The West would make an excellent starting point. •

The West: A New History of an Old Idea

By Naoíse Mac Sweeney | WH Allen | $35 | 448 pages