Sylvie Leber describes herself as a “ratbag.” It’s in the blood, she says. Sylvie attended her first protest in 1967, age sixteen, joining a crowd gathered at Melbourne’s Government House to oppose a visit by Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, prime minister of South Vietnam and a vital American ally in the prosecution of the Vietnam war. Many more protests have followed. She’s been roughed up and worn bruises but never arrested, she says with a hint of surprise. Probably it’s a matter of time. Now in her seventies, she’s still raising her voice for social justice.

Her causes are many and diverse, but linked by a unifying thread: always, Sylvie sides with the oppressed. For nearly sixty years she has fought for women’s rights, refugee causes, and for anyone whose treatment she deems unfair. Perhaps the best measure of her conviction is that she holds fast to causes, even at risk of personal cost.

Sylvie traces her radical roots to her Jewish paternal grandparents, David Leber and Rivka Szaladajewska, whose motivating creed was social and political change. Rivka was born on 26 September 1896 to an observant Jewish family in the Polish city of Łódź. She would later reject religion, and her family her, but she maintained a cultural and social connection to Judaism, working at the Grosser orphanage for Jewish children in the central Polish city of Piotrków Trybunalski. Her fierce commitment to the politics of the left, at a time when Jews were among the most prominent advocates for social democratic causes in eastern Europe and Russia, was another point of connection to her Jewish heritage.

David Leber was born in Piotrków Trybunalski, Poland, on 10 January 1887. While the details of his early life are sketchy, he was motivated from a young age by the tenets of social democracy. He was schooled first at a yeshiva, but left religious education to embrace Bundism, the influential secular Jewish movement that agitated for social and labour reform.

Bundism led David to Russia, and trouble. The February revolution of 1917 saw Bundists and Mensheviks align in a union of social democratic parties. When the February, or Menshevik, revolution was supplanted in October by the more radical Bolsheviks, the Bundists who supported Menshevism became pariahs, dismissed by the new regime as ineffectual gradualists and enemies of the communist state.

Though not a Menshevik himself, David was damned by association. His link to the Menshevik cause appears to have led to his arrest and deportation to Siberia. An accusation that he had sought to assassinate a public official may have been the pretext for his arrest. Whether or not he escaped from Siberia or was released, he is thought to have been rescued from the Soviet Union on a British ship.

Now back in Poland, David found work as a waiter, and met Rivka. Worsening anti-Semitism prompted them to leave their homeland for France in 1922. Rivka was pregnant when they made their way west, and a son, Samuel, was born in Paris on 3 December 1922. Against Jewish custom he was not circumcised, and David and Rivka didn’t marry until twelve years after his birth, with Rivka keeping her maiden name. Her choice to be known as Rivka Szaladajewska was both a stab at patriarchal custom and an affirmation of identity. Others might have seen the Polish suffix “jewska” as a millstone, but not her.

David and Rivka became part of a Parisian left-wing milieu that included other Jewish émigrés, among them the Russian-born artist Marc Chagall, with whom they became good friends. John-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir were part of the same circle. David and Rivka brought their passions with them to Paris: they were united in their dislike of conventions for which they saw no purpose and in their commitment to social democratic principles and secularism. David continued to see these beliefs as inherent in Bundism: his experiences in Russia didn’t dim his enthusiasm for the Bundist approach to social change. A manifestation of his commitment to community and history was his involvement in founding the Medem Library in 1929, which is still the most important site of Yiddish learning in Europe.

David and Rivka were two of the thousands of Jews ensnared in 1942 by Operation Spring Wind, in which officials of the Vichy French state cooperated with the Nazi regime to arrest foreign and stateless Jews living in France. The operation was the first step in a plan to send Jews east to Auschwitz and their deaths. The two of them were arrested on 16 July in the infamous Vél d’Hiv round-up, interned at the Drancy transit camp in Paris, and then deported to Auschwitz on 24 July as part of convoy number 10. They were killed at Auschwitz, probably later in 1942, though when exactly isn’t certain. Rivka is thought to have taken her own life, throwing herself on an electric fence after she learnt that she was to be a victim of one of Josef Mengele’s depraved experiments.

Two years earlier, when the Germans marched on Paris, Rivka and David’s son Sam was a seventeen-year-old school student living with his parents in the 20th arrondissement. His response to the German advance was to cycle to the port of Royan on the Atlantic coast in the hope of finding passage to England. This plan failed and he returned to Paris, where he remained until November 1941, when David and Rivka compelled him to leave the city for Lyon in the zone libre, where he lived with friends.

German occupation of the zone in November 1942 prompted Sam to move to Grenoble, where he worked as a lathe turner before being corralled into the Chantiers de la Jeunesse Française, a national service scheme imposed on French youth by the Vichy state. Released from this obligation in mid 1943, he managed to avoid another, more insidious labour scheme — the Service du Travail Obligatoire, which sent young French men to Germany as indentured labour — by joining the Resistance in late 1943 or early 1944.

For life as a maquisard, Sam chose the stirring alias Serge Rebel, his new surname a testament to his task and heritage: Rebel is the anadrome of Leber. From David and Rivka he had inherited a commitment to the ideals of Bundism and socialism. He had joined the SKIF, the youth wing of the Bundist movement, in 1931, the year he turned nine. A strong anti-communist streak may have been another inheritance, though his opposition was fed also by his own experiences.

During the Spanish civil war of 1936–39, he had travelled to Spain to fight with the Republicans against Franco’s Nationalist forces. He was turned away on account of his youth, but took from the war an understanding that communists had undermined the Republican cause by concerning themselves more with anarchists than fascists.

His dislike of communism hardened when the French Communist Party, echoing Moscow’s line, adopted a neutral position at the start of the second world war, a stance he thought amoral and hopelessly naive. Later, in the Resistance, he objected to the division of the organisation along communist and anti-communist lines as a needless distraction. In his thinking, communists too often missed the point of the fight. And the point of any battle was to act, not to posture.

In the Resistance Sam worked in intelligence and sabotage. He and his fellow maquisards couldn’t spare explosives to destroy railway tracks so prised them out of position, ensuring that carriages travelling the tracks at Grenoble, an important railway junction connecting different parts of France, would tip over. Precious explosives were reserved for attacking factories that sustained the German war effort. In one instance, Sam recalled, bombs were used to kill German soldiers, but more often their targets were objects rather than people, collaborators aside. For traitors, direct violence always seemed justified.

Sam served with the Resistance until the liberation of France. His rewards were the Croix de Guerre, citations for brave conduct and good service, and a bullet wound, sustained during a firefight with German soldiers in March 1944, which led to three months in hospital, a shortened leg and a permanent and painful limp. Several decades on, Sam was diagnosed with motor neurone disease, which doctors linked to spinal damage caused by his limp.

In later years Sam mentioned his war rarely, and usually only when pressed. School students and Holocaust historians sought him out for interviews, seemingly surprised to find a decorated maquisard living in McKinnon in suburban Melbourne. Sam obliged these requests, with humility and a trace of bemusement. He had fought the war against fascism as a solemn and obvious duty, a position that precluded the shaping of recollections as personal achievement. The fact he was speaking in his third language, after Yiddish and French, may also have shaped his responses, which could seem blunt.

“Sometimes an action went wrong and people got killed and things like that,” he told two interviewers in the 1980s. Nazi collaborators, he added, were “interdicted” on their way to or from work. These answers, on first reading dispassionate and perhaps even callous, did not reflect the man. Rather, they hint at Sam’s lifelong and noble belief in the primacy of the collective cause over the claims of the individual.

After the war Sam returned to Paris, a city that had visited both kindness and cruelty on the Lebers. His parents had found blessed sanctuary there in the 1920s; twenty years later, it was the place of their betrayal. He met Madeleine Benczkowski, and they married in 1948. His new wife, also French-born of Polish Jewish heritage, had been born in Paris on 20 January 1926. Her parents, Herschel and Chaya Benczkowski, had emigrated west from Poland in the years after the first world war.

Herschel was murdered at Drancy in 1942. Madeleine, her brother Sam and their mother Chaya survived the war thanks to the people smugglers who spirited them from Paris to Lyon, where they lived under false names and Madeleine was able to earn money as a furrier’s apprentice. In Madeleine’s vocabulary, “people smuggler” could be a term of endearment and a pejorative. She knew three types of people smuggler — humanitarians, money-makers and “bastards” who betrayed Jews to Nazis. The Benczkowskis’ saviour was a humanitarian and a money-maker, having taken payment in jewellery.

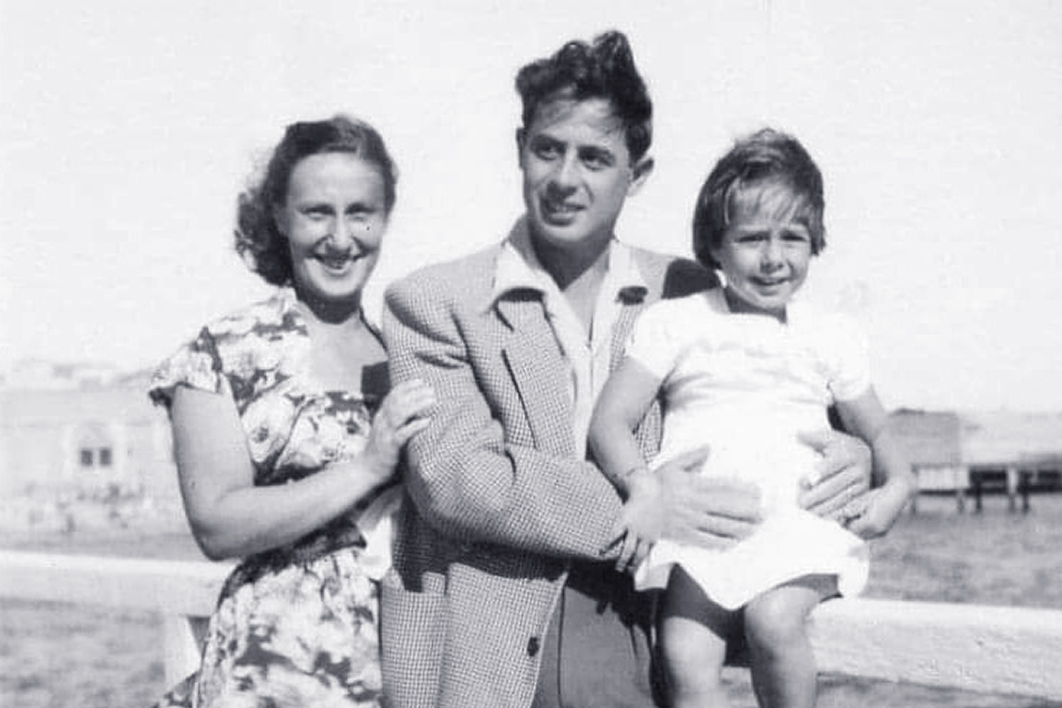

Sam and Madeleine began their married life in Paris as tailors, making men’s trousers from home. Their daughter Sylvie was born on 30 May 1950. The next year they resolved to emigrate to Australia, their decision to leave France prompted by the Korean war and the threat of another world war. They considered Canada, but chose Australia on the advice of Rose and Leon Goldblum, Sam’s cousin and her husband, who were living in Melbourne and recommended the city as a good, safe place to raise children. Rose and Leon were Auschwitz survivors. A preference for a warmer climate may also have influenced Sam and Madeleine’s choice. The Lebers sailed on the Italian ship Sydney, arriving at Station Pier, Port Melbourne, in February 1952.

The family settled into Australian life in Grey Street, St Kilda, within a milieu that offered comfort and connections to the world from which they had come. Melbourne in the 1950s, and St Kilda in particular, was home to a community of French-speaking Jews from France and Belgium. In their company Sam and Madeleine found friends with whom they shared a common language and aspects of a common heritage. As for so many other migrants across time and place, such connections to the familiar were a sustaining tonic in difficult years.

Before the war, Madeleine had hoped to be an accountant, Sam an engineer. After the war, steady work and a safe home were aspiration enough. Madeleine sought work as a jewellery shop assistant but was rejected on account of her French accent, so she returned to what she knew, working from home as a seamstress. Sam worked as a toolmaker, and fitter and turner. He joined the Australian Metal Workers’ Union: the union movement, and the postwar Australian Labor Party, reflected some of his Bundist ideals.

For Sylvie, the initial contrast between life in Paris and life in Melbourne was less abrupt than it was for her parents. She spoke French at home and Yiddish at her kindergarten at the Bialystoker Centre at 19 Robe Street, St Kilda, which served also as a hostel for Jewish migrants and refugees from Europe. The Alliance Française, where Sam and Madeleine borrowed French-language books, was on the same street. Such was Sylvie’s immersion in this European milieu that she knew little English when she started at St Kilda Park Primary School. Daniel, her brother, was born in 1959.

***

If Sam, who died in 2011 aged eighty-eight, was an “activist,” he probably didn’t recognise it. His engagement with the political was not a conscious choice but the manifestation of a commitment to social democratic ideals; in his conception, actions gave honour and worth to thoughts. To be political, if that’s what others called it, was simply his way of being.

Sylvie has followed the same path, her activism inseparable from her work and passions. In this regard she is her father’s daughter. Madeleine, who died in 2015, was a quieter social democrat than her husband: she voted Labor and hoped for a society ordered on fairness and merit rather than money and privilege, but was not overtly political.

In 1979 Sylvie and her friend Eve Glenn formed Girl’s Garage Band, a seven-woman punk rock band with Sylvie on bass guitar, Eve on lead guitar, and Fran Kelly, not yet an ABC journalist, on vocals. The band became better known as Toxic Shock, the name a pointed reference to the bacterial syndrome associated with tampon use that at the time was harming and killing many women. The band’s 1981 single “Intoxication,” written by Sylvie, protested at the complicity of tampon manufacturers in the prevalence of the syndrome.

Through Toxic Shock, Sylvie could voice specific protest, rail against the patriarchal nature of the punk and post-punk scenes and the music industry generally, and express her passion for music. Give-Men-a-Pause, a women’s music show she hosted on 3RRR in the early 1980s, offered another stage to voice thoughts on life and music. In a 2015 article about the contemporary Australian popular music scene, she wrote of her enduring love for playing and listening to music, and her dismay at the persistence of the boys’ club that Toxic Shock strove to disrupt.

For Sylvie, music has been a passion, a motivation and, on occasion, a refuge from horror. In Queensland in 1972, some years before forming Toxic Shock, she was raped and very nearly murdered. She has written with compelling honesty of these crimes, the toll they have taken on her mind and body over half a century, and her determination always to fight back lest “the bastards win.”

Her response to the assault might be described as Leberian, for its hallmarks are concern for others and a remarkable and enduring capacity to resist. Initially she sought to shield her parents from the attack, worried that they, as European Jews who had lived through the war, had experienced enough anguish. Later, her understanding of the Lebers’ commitment to social justice motivated her to speak publicly about what she had suffered. A year after she was assaulted, she and a group of friends founded Women Against Rape, Victoria’s first rape crisis centre, housed within the Women’s Health Centre on Johnston Street, Collingwood. Women Against Rape supported victims in every way possible, while advocating simultaneously for legal change and community education.

Sylvie is a passionate advocate for the rights of refugees and asylum seekers, the experiences of her parents and grandparents having taught her something of the pain and indignity of being denied a home. When Arne Rinnan, captain of the infamous MV Tampa, made his last voyage into Australian waters before retirement, Sylvie and other Melbourne members of the Refugee Action Collective took to a small boat so that they might approach his cargo ship and salute him for his role in rescuing imperilled refugees during the Tampa affair of 2001. Rinnan’s moral example elicited an idiosyncratic touch: to signal her admiration, Sylvie fashioned a placard decorated with a love heart. Love, Sylvie believes, “is a revolutionary emotion.”

Sylvie named her daughter Colette Anna — Colette for the pioneering French author and feminist, and Anna for a great aunt who survived Auschwitz. Colette is a social worker, committed to many of the same causes as her mother. She works to prevent violence against women, and argues for the rights of refugees, including protesting their abysmal treatment by Australian governments, Liberal and Labor. Colette is another Leber ratbag, which makes her mother proud. It’s in the blood. •