Over the past decade, under president Xi Jinping, China’s Communist Party has stepped up its efforts to subjugate history. Interlinked and increasingly high-tech mechanisms of surveillance, control and censorship are today on high alert for outbreaks of what the party calls “historical nihilism” — any telling of history that deviates from the official narrative in which the party is and always has been Great, Glorious and Correct.

A famine that killed tens of millions of people? Blame it on natural disasters and that damn Khrushchev. Political campaigns that became wildly murderous? Not our fault — those excesses were the work of overly zealous, even rogue, local officials. Any awkward truths that can’t be swept under the carpet must be explained away, woven together with half-truths and lies into the fringe of the carpet itself.

Journalist Ian Johnson’s new book, Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future, relates the stories of people, extraordinary in their tenacity and courage, who persist in peering at the mess under that carpet and unpicking the tightly knit threads. They sneak their cameras into former labour camps to reveal human bones still protruding from the soil, interview the last survivors of famines and massacres, and create online archives and offline samizdat journals to record their findings. Among their number are the “citizen journalists” who record history in the making, including those who documented scenes in hospitals and elsewhere in Wuhan during that city’s draconian Covid-19 lockdown in early 2020.

For thousands of years, as Johnson notes, history has been “inseparable” in China from the concept of moral instruction. The independent researchers devoted to historical investigation he is writing about believe that “a moral society cannot be based on lies and silence.” But to refute the lies and break the silence, these intrepid men and women, sometimes armed with little more than curiosity, a smartphone and internet access, must play a dangerous cat-and-mouse game with security forces.

Many do their work under suffocating levels of surveillance. Others have been put under house arrest or worse, with some prison sentences longer than those handed out to convicted rapists. If they risk their freedom and even their lives to shine a light into some of contemporary Chinese history’s darkest corners, they do so because they believe that “the party’s monopoly of the past” is “the root of their country’s current authoritarian malaise.”

These “counter-historians” are generally less interested in the elite machinations behind catastrophic events than the “degradation of the individual” after the events have been set in motion. To discuss the culpability of party leaders would be asking for even more trouble, of course. But they are genuinely devoted to recovering and honouring the stories of ordinary people. At the same time, Johnson writes, they tend to avoid “heroizing” the victims. The histories they produce may necessarily be incomplete, but they are persuasively nuanced.

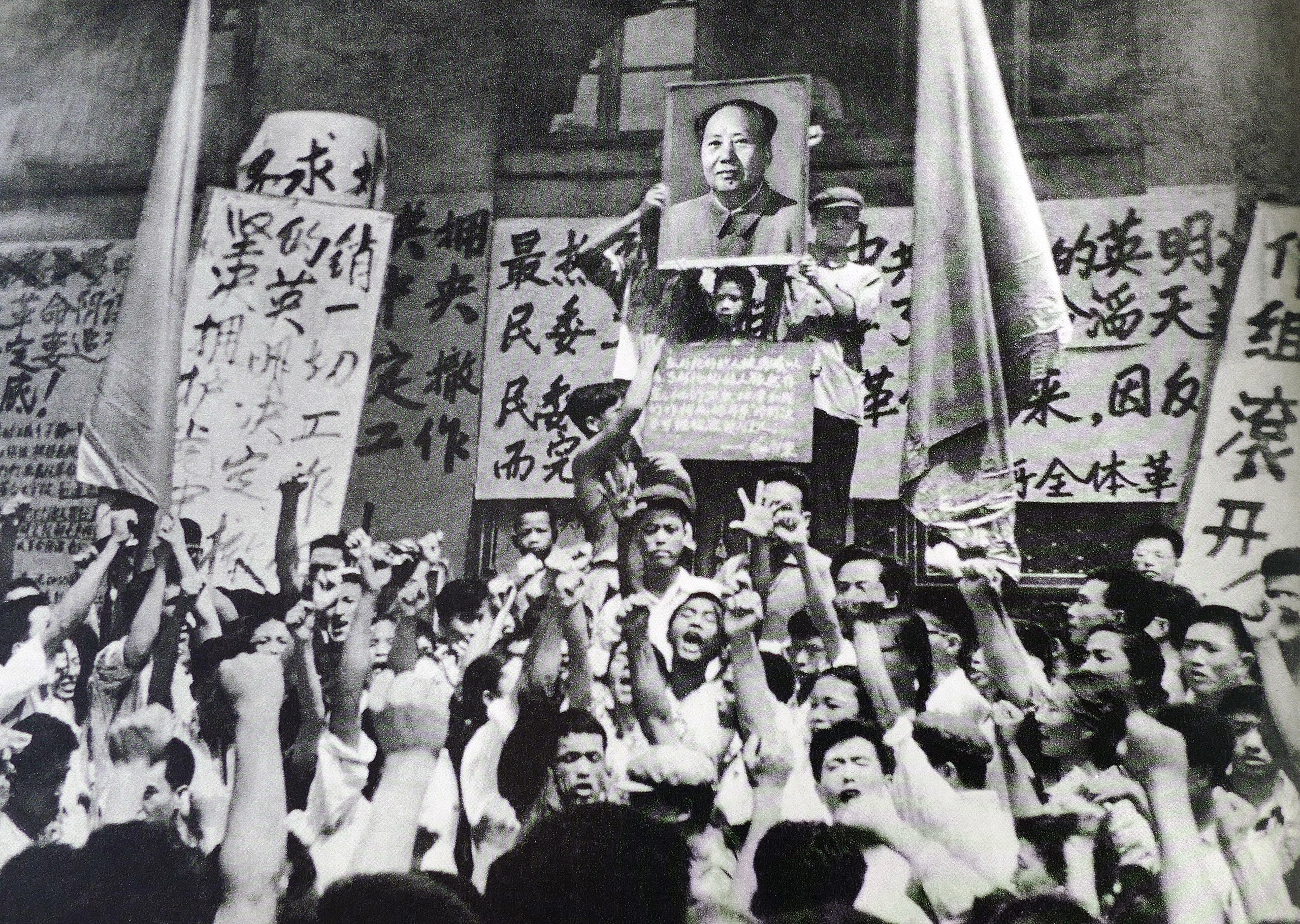

The carefully constructed official history, by contrast, is intolerant of nuance or deviation. Engraved in textbooks, promoted in films, enshrined in museums and embodied in the sacred sites of “Red tourism,” it lies at the heart of the party’s legitimacy. It narrates the story of how the communists saved the Chinese people from a “feudal” past as well as the Japanese enemy without and the class enemies within. It tells how the party has kept China safe in a hostile world, governed it wisely and justly, and raised it from poverty to prosperity and power.

Over the past eighty years the party has produced three historical resolutions, “each a cartoonish version of history” intended to justify the rule of the latest leader. The official history endorses the party’s right to rule China today, more than seventy years after the revolution that brought it to power. It paves the way for that rule to continue into the future without any need for checks and balances or popular elections.

To raise questions about the great famine or the systemic nature of the violence during the land reform era or the Cultural Revolution is to ask, in effect — why are you still the boss of us?

The party watched with apprehension and then with horror as the policy of glasnost (transparency) championed by Gorbachev in the mid 1980s led to a rush on the Soviet Union’s historical archives. Soviet citizens were suddenly free to remember and discuss the savagery of the Stalinist era: the political purges, the famines, the midnight knocks on the door, the desolate and murderous gulag of labour camps, the ruined and wasted lives. Just six years later, the Soviet Union collapsed.

Lesson taken. The Chinese Communist Party’s post-Mao leadership, also shaken by the mass pro-democracy protests of 1989, tightened control over political and intellectual discourse. Yet independent thinkers, many of whom had personal experience of upheavals like the famine and Cultural Revolution, both as participants and victims, were compelled to record, research and analyse. Work that couldn’t be published in the mainland was frequently published in Hong Kong.

Among those who laid the path walked by the generation described in Sparks were the oral historian Sang Ye, the writer Liu Binyan, the historical investigator Dai Qing and the journalist Yang Jisheng. If there is one criticism I have of Sparks, otherwise an exemplary, well-researched and vital book, it’s the author’s failure to mention these pathbreakers, the post-Mao pioneers of the movement to which the people he writes about belong. Another curious omission is Wang Youqin, whose epic archival work on the victims of the Cultural Revolution was published in English in an abridged and edited form in 2023.

Johnson’s focus, however, is on more recent times. He observes that a confluence of events and trends in 2003 led to a surge in grassroots history writing. Contributing factors included popular outrage over the government’s suppression of news about the SARS epidemic that year and the application of market forces to Chinese media, which led to a partial liberation from direct control by the party. Xi Jinping’s ascension less than a decade later marked the end of this brief golden age and the beginning of what Johnson describes as Xi’s “forever crackdown” on “historical nihilism.”

And yet the independent historians persist, driven by the importance of what they are doing. The focus of their work may be as narrow as the experience of a single county in a single month of the Cultural Revolution or as broad as the question of guilt and the value of apologies. Collectively, their work reveals that even when the Communist Party shifts the blame for mistakes and crimes onto a few bad eggs, it rarely punishes them, and if so, even more rarely to any degree commensurate with their crimes. They also demonstrate that violence has always been far more pervasive and systemic than the official story suggests.

It’s not just the Communist Party that resists telling these stories. Many of those who have suffered through the events these historians are studying don’t want to talk about them. Some just want to put the trauma behind them. Others don’t want to get in trouble or jeopardise their children’s futures. They have buried the past to rebuild their lives as though, Johnson writes, “The suffering somehow cheapened this world of newfound prosperity, a reminder that it was built on violence.” In a different context (the Wondery podcast Ghost Story) the British historian Nicholas Hiley has discussed the “destabilising” nature of revealed historical truth — the past is not always a happy place and the truth does not always set people free. And yet we carry that past around with us — and it informs the present whether we like it or not.

Ian Johnson is a veteran, Pulitzer Prize–winning China journalist and a Sinophone whose work balances academic rigour with good storytelling. Sparks is the culmination of years of meeting with and even going on reporting trips with the underground historians he profiles here. He inserts between the chapters short vignettes, “Memories,” that offer, in his words, “sketches of people, places, and iconic works of counter-memory that demonstrate the ambition of China’s underground historians: to write a new history of contemporary China in order to change their country’s future.”

Sparks takes its title from a samizdat journal from the 1950s whose history has been uncovered by one of the historians Johnson profiles. The book joins a growing list of publications in English that together are creating a far richer picture of China’s history than that to which non–Chinese speakers have previously had access. They include works like Yang Jisheng’s Tombstone and Wang Youqin’s Victims of the Cultural Revolution, both of which were edited and translated by Stacy Mosher and Guo Jian; Louisa Lim’s brilliant Indelible City, about Hong Kong; Jonathan Clements’s essential new history of Taiwan, Rebel Island; and Tania Branigan’s Red Memory, in which Wang Youqin features heavily.

Johnson contends that the “vibrancy of China’s counter-history movement” — which also includes creative reconstructions of historical events and personages by artists and writers — “should force us to retire certain clichéd ways of seeing China.” These include the tendency to see its authoritarianism as successfully monolithic. While not denying that “these are dark times,” he champions the counter-history movement as a significant form of resistance. As one of the young members of the group behind the original samizdat journal Spark put it back in the 1950s, “If you do not break out of silence, you will die in silence.” •

Sparks: China’s Underground Historians and Their Battle for the Future

By Ian Johnson | Allen Lane | $55 | 400 pages