“The middling sort” was a term used in the eighteenth century to describe those people, neither wage labourers nor gentry, who were the forerunners of the modern middle class — shopkeepers, manufacturers, skilled artisans, professionals and even yeoman farmers — people who “shared values and expectations that were shaped by the dangers of the commercial world… temperate, prudent, proud of their independence.”

Historian Marian Quartly borrows the term to describe her ancestors in her new book The Middling Sort: A South Australian Family History. All English, Quartly’s forebears came to South Australia as assisted immigrants from 1849 onwards and became part of the settler society that developed there. They had been shopkeepers, innkeepers, rural labourers and the like — a provenance, she remarks, that “means that my story does not include some of the great themes of Australian history: I have no convicts in my ancestry, no Irishmen or Irishwomen, no Catholics.” But she has more than her fair share of “petty capitalists, dissenting Protestants, temperance advocates and small landholders.”

Quartly’s own preferred term is “citizen capitalists.” By this she means that families on both sides, though mostly landless labourers from England, managed to become property owners of various kinds. At times they still needed to sell their labour, but in many instances they bought and sold houses and town land and set up small businesses — with varying success depending on the state of the economy and their own circumstances. But her family, she rightly says, would not have agreed that they benefited from a class system; they would instead have insisted that their successes had all been by their own efforts. They would have seen themselves as people “of the middling sort.”

This book is an account of “three generations of women and men whose lives were part of the British invasion of Australia.” Quartly continues: “it uses the history of one family — mine — to explore those connections” with the communities that its members belonged to and helped to form. She does not set out to dissect the “beautiful lies” that Mark Twain once discerned in the stories he was told about the planned colony of South Australia — though she does identify a few of those among family legends — but rather to change the focus from public to private, from large institutions to families, their formations and their livelihoods.

As narrator of this family history, Quartly addresses general readers as well as family. The book is dedicated to her grandchildren and to Great-Aunt Ruby who first made her aware, as a girl, that she was indeed “part of history.” The professional historian is there, all the same. Her research interests in the history of the family, religion and gendered citizenship identify Quartly as part of the major reorientation of Australian historical studies over the past fifty years. Addressing her grandchildren, she emphasises that the stories she tells are part of this new kind of history, which includes “women as well as men, followers as well as leaders, first nations people as well as invaders, family life as well as politics” and takes “affection and fear and religious experience and family violence seriously as historical phenomena.”

These are the themes uniting a narrative that uses family stories, both written and oral, and public sources such as court records, land titles and newspapers, a traditional source now greatly enhanced, as she says, by the availability of older city and regional newspapers through Trove.

The stories also link the fortunes of the families to economic and social developments in the colony: their religious affiliations, the way key legislation on land selection and public education affected them, and how their work related to the growth and decline of various productive and extractive industries in an economy that remained essentially rural during the period of this history.

Out of a plethora of names, dates and places, she has structured five chapters, each of which tells stories from one branch of the family tree from its early nineteenth-century origins (mainly in rural England) through the decision to emigrate to the places of eventual settlement — mostly in South Australia but one in Albany, Western Australia.

She begins and ends with her father’s family. Her father’s great-grandparents, Charles and Maria Hall, emigrated to Van Diemen’s Land in 1841 when he was appointed a government schoolmaster, along with several other Dissenters, at the request of Governor Franklin. He had been a student at the Homerton College in Hackney, described as “a centre of ‘Dissent’ — religious and educational activity by Christians whose beliefs did not conform to those held by the official Church of England.” Tensions between the established Church and his Congregationalist beliefs led Charles to leave for South Australia in 1849 and take up a series of clerical appointments in and around Adelaide. As a man of God, continually examining his conscience, he kept diaries, one of the few such sources available to the family historian. These reveal him to have also been a despotic paterfamilias who required his children to marry up in social status.

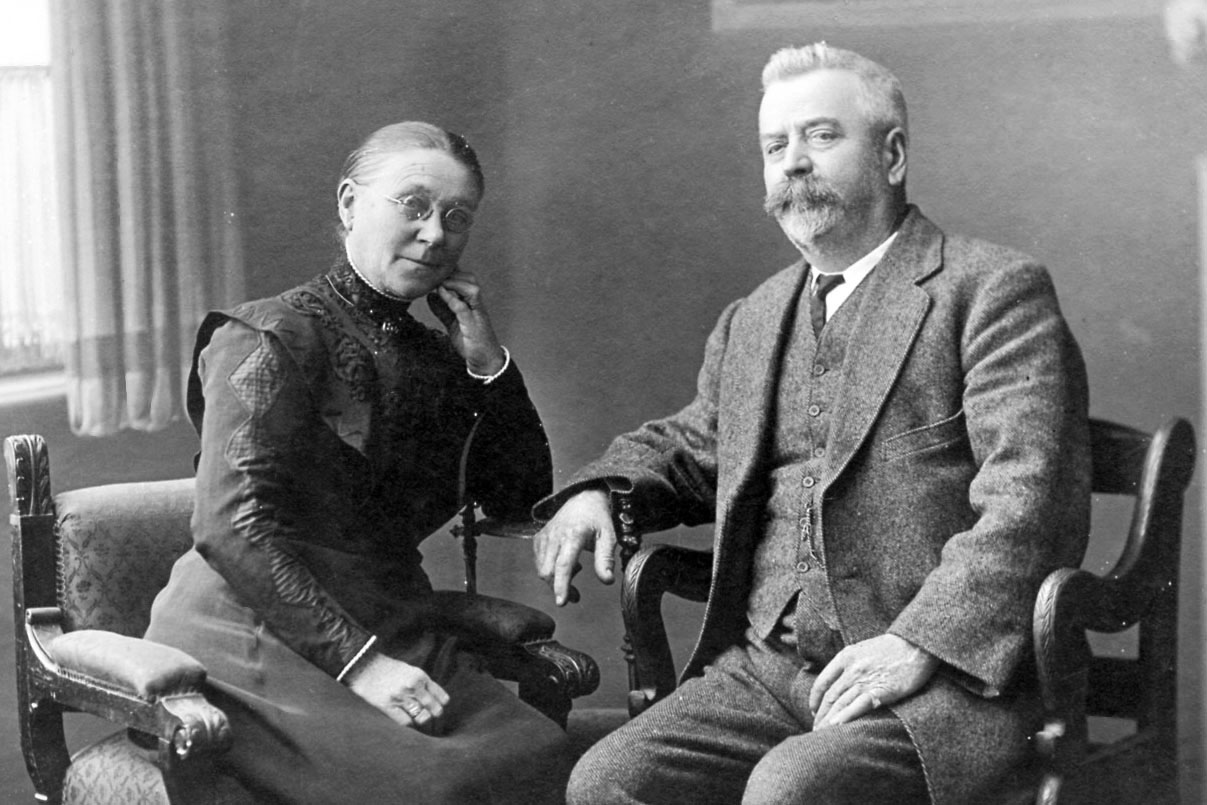

The Quartlys, another family of Congregationalists, come into the picture next. They also arrived in Adelaide in 1849 and set up a grocery business in Hindmarsh, a new suburb where Henry Quartly was involved in the establishment of the District Library and Institute and other community-building. The marriage of their son William Quartly to the youngest Hall (Lydia or “Lillie”) in 1880 might not have satisfied her father’s social ambitions but it brought material security to the ageing Halls. In their later years they lived in Adelaide’s eastern suburbs, near the villa that Lydia occupied in fashionable Burnside while her husband remained in Minlaton, on the Yorke Peninsula, pursuing his various interests. This was the first of a string of uneasy or broken marriages in the family.

Marian’s mother was descended from a cluster of assisted immigrant families — Tylers, Kurlls, Baileys and Lawsons — who settled in the Wandearah area north of Adelaide in the 1850s. At first they worked the land as tenant farmers growing wheat; then, after the land reforms of the 1870s, most acquired land or town properties of their own. They were enterprising selectors, introducing innovations in order to wreak their victory (as they might have seen it) over fragile, drought-prone country.

Marian’s paternal grandmother’s family, the Andrews, migrated to Western Australia in 1865 but had connections with Adelaide. Another authoritarian father, Edward Andrews followed a succession of trades and held considerable standing in the town of Albany when he was convicted, in 1901, of assaulting his wife, Caroline. She, with her younger children, was already living separately from him, her independence apparently enabled by an inheritance from her family in England. She obtained a “judicial separation” (divorce being difficult if not impossible) and Edward returned to England, having been forced to pay a settlement and grant her custody of those of her eleven children who were still dependant.

One of Caroline’s adult children, Adelaide (Addie), would in 1903 marry Harry Quartly, a clerk in the timber mill at Denmark, where her brothers lived. The book’s final chapter, “An Unhappy Marriage,” focuses on this couple, the author’s father’s parents. It is a sad story, one that he rarely spoke of, and Quartly writes that it is “for him.”

Her father (also Harry) was born in 1909, after his parents moved to South Australia to live. His father seems to have been a personable man, and a successful accountant, whose talents in recitation were much in demand on social occasions. But he had a lasting problem with alcohol, which involved him in the shame and disgrace of several tangles with the law. When he eventually deserted the family, Addie and her three children were left to struggle through. At first the children were separated from their mother and each other, with Addie working as a housekeeper for some years until she was able to acquire (by purchase or lease, the documentation is missing) a house big enough to run as a boarding establishment and reunite her family. They were not to see their father again.

What is striking about these stories of strained or broken families is that in each case the woman attained a degree of independence. Lillie and Caroline both owned houses in their own names, and although Addie had independence thrust upon her by her husband’s desertion she, like many a woman before her, ran a boarding house so as to keep a home for her children; later her daughters bought her a house of her own, where she earned a living by nursing a series of women from wealthy families through their final years.

Another feature of women’s lives, one that is difficult for the historian to document without diaries or letters, is their probable participation in family businesses, whether in the daily round of farming or shopkeeping or inn-keeping, or in decisions about the sale and acquisition of properties — activities that enabled the “citizen capitalists” to operate so successfully. My awareness of these female contributions to family fortunes has been heightened by having recently read Kate Grenville’s story of her grandmother, Restless Dolly Maunder, who she portrays convincingly as the driving force behind her family’s material success in the early decades of the twentieth century.

This reflection led me back, in turn, to Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall’s definitive study, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class 1780–1850 (1987). They demonstrate that women’s work was a recognised and valued contribution to family-based enterprises, from farming to shop-keeping, which were characteristic of the middle class in this earlier period of the Industrial Revolution. They also show how religion, especially dissenting forms of Christianity, was key to family, business and public life. This was, surely, the England that the “citizen capitalists” of The Middling Sort had emigrated from. It was their combination of Dissenting religion and small family business enterprises that proved so influential in the formation of a settler society in South Australia that was to remain mainly a rural economy until the mid-twentieth century.

Marian Quartly’s concluding reflections on the role of her family and others like them, people of “the middling sort,” in the making of the old British-based settler society in Australia include reference to Judith Brett’s Robert Menzies’ Forgotten People (2007). Brett characterises the middle class as “a projected moral community” whose members valued independence, enterprise and respectability, and argues for their formative historic role. It is a definition that the families described in this history would probably have accepted. •

The Middling Sort: A South Australian Family History

By Marian Quartly | Quartly | $45 | 187 pages