The Paris Olympics inevitably provoked memories of past Games, and especially sporting feats with broader repercussions: Jesse Owen’s gold medal sprint during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, for example, or Tommie Smith’s Black Panther salute after winning the 200 metres in Mexico City in 1968, or the “blood in the water” encounter between Hungary and the Soviet Union during the Melbourne Games. But few remember sailor Rolf Mulka’s bronze medal in the Rome Olympics in 1960.

Mulka and fellow German Ingo von Bredow won their medal in the Flying Dutchman class. Mulka had already won the world championship twice, and this third place could be considered disappointing. But the main effect of his podium finish in Rome was unrelated to his sporting feats. Back in Germany, somebody noticed his unusual surname (even today, only ten Mulkas are listed in German phone books). Could it be that Rolf was related to Robert Mulka, second-in-command of the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1942 and 1943?

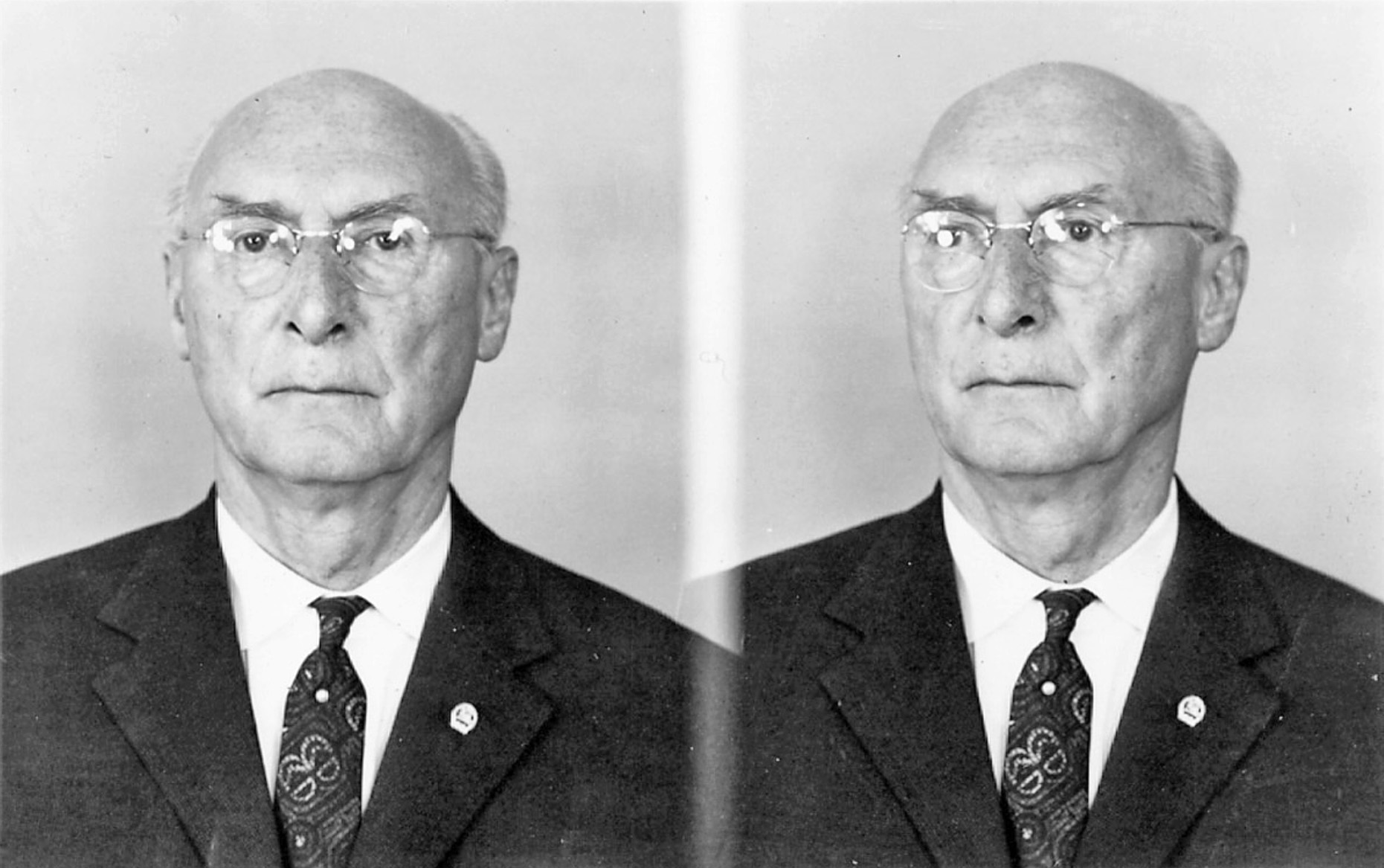

Rolf Mulka’s brief moment in the Rome limelight led a Frankfurt prosecutor to track down his father Robert, now a businessman living in Hamburg. The 1963–65 court case v. Robert Mulka and others — commonly known as the first Frankfurt Auschwitz trial — changed the way West Germans viewed the Nazi past. Mulka himself was sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment for aiding and abetting the murder of 750 people on each of four occasions.

Mulka’s was not the first major trial of Nazi perpetrators under postwar German law. That distinction belongs to the Ulm war crimes trial of 1958, in which ten former members of an Einsatzkommando were convicted as accessories to mass murder carried out in 1941 in occupied Lithuania. But the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial was the most consequential and remains the Federal Republic’s best-known attempt to hold Nazi perpetrators to account. What is perhaps the last such court case has just come to an end, with the federal court upholding the conviction for murder of a ninety-nine-year-old woman who once worked as a typist at the Stutthof concentration camp.

Although it may be the last, that conviction is unlikely to bring about a sense of closure. Germany’s Nazi past, which has loomed so large in the Federal Republic’s first seventy-five years, is likely to remain alive in years to come. At least so far, all attempts to treat the years from 1933 to 1945 as merely one episode in a history that reaches back well into the Middle Ages — a “piece of bird shit” as a former leader of the far-right Alternative for Germany, or AfD, once famously called “those twelve years” — have been unsuccessful.

Frank Trentmann’s Out of the Darkness, a monumental new history of contemporary Germany, tries to grapple with the legacy of Germany’s Nazi past. In particular, he is interested in Germans’ moral identity — “their changing sense of right and wrong through what they actually did.”

In a bold and welcome move, Trentmann’s history of “the Germans through a moral lens” begins not in 1945, with the defeat of Nazi Germany, nor in 1949, with the founding of the two postwar German states. Rather, it opens in 1942, and not with Auschwitz but amid a conflict in which “war crimes were an integral part of German warfare, not an aberration.”

Out of Darkness amounts to nothing less than a cultural history of Germans, covering topics from their volunteer activities to the reception of refugees in the immediate postwar era, and from the West German peace movement to the turbulences that precipitated the fall of the Wall. In fact, Trentmann’s interest in a vast range of themes occasionally made me look again for the narrative glue that held them together. But anybody who perseveres until the end of this book will have learned a lot about the peculiarities of Germans and of Germany.

The uneven narrative is at its most convincing when Trentmann is able to draw on a rich archive — a cache of letters, for example — but less convincing when we reach the last twenty or thirty years and he relies more on the results of social scientific surveys than on the anecdotal evidence provided by written sources.

His project is also contradictory. “Historians should not try to compete with moral philosophers in offering normative accounts of the world,” he writes in his introduction, and his own account is thus that of an academic historian striving to offer a “nuanced story” who often qualifies his statements. Numerous “yes, but” cautions and his tendency to furnish evidence for uncontroversial statements such as “for every success story it is possible to find a not-so-successful one” add to his narrative’s length and impedes its readability.

Despite Trentmann’s intentions, Out of Darkness is also a scathing critique of Germans and of contemporary Germany. Germans are self-interested and inward-looking, he argues. Their field of vision “has been provincial.” For example, the country’s much-lauded Energiewende (the turning away from fossil fuels towards renewable energies) “has been a balm to [Germans’] conscience, making them feel like ecological trailblazers or at least creating the comfortable illusion that wind and solar will fix the problem, without change in their own lives.” As a German expatriate living in Britain, his critique of — and at times contempt for — contemporary Germans is that of an insider looking at his country from outside.

I found Trentmann’s critical engagement with Germany — though sometimes needlessly undercut by those scholarly provisos — one of the strengths of the book. In particular, I liked his emphasis on Germans’ solipsism and introspection (which I would prefer to call narcissism, because that term also draws attention to Germans’ tendency to self-admiration). Whether it has been their coming to terms with the Nazi past, their solidarity with distant others or their care for the environment, too often Germans are driven by a moral vision that is self-referential. Trentmann suggests that this is the characteristic contemporary Germans share with their forebears in the early 1940s.

Analysing the diary entries of a young German officer who found the “cruelty, badness, betrayal and cowardice” surrounding him in the second world war repulsive, he shows how that man’s “agitation about the brutal killings, plunder and mayhem arose not from concern about the suffering of others but from the challenge it posed to his own self-image as a pure, noble knight.”

What’s not sufficiently highlighted in Trentmann’s account is a closely related mental disposition that survived the end of Nazi Germany: indifference. Indifference, rather than outright anti-Semitism, marked the attitude of most non-Jewish Germans towards the deportation of their Jewish neighbours. Indifference toward the victims of Germany was on display in the 1950s and 1960s. Now, indifference rather than outright racism informs most Germans’ stance towards refugees seeking protection in Europe. Indifference towards the suffering in Gaza, rather than support for Israel, informs most Germans’ views about the conflict in Palestine. Indifference towards those in the global south who have to endure the consequences of global climate change informs many Germans’ reluctance to reduce carbon emissions.

Rather than Germans’ enduring indifference, Trentmann focuses on their striving for atonement. As a religious concept, atonement allows the sinner to make up for having offended God; even injustices perpetrated against a fellow human being are essentially insults of God. As a non-religious concept, it refers to the self-imposed efforts of a wrong-doer to right a wrong she has committed. Both theological and non-theological understandings also allow for acts of atonement to be carried out on behalf of a wrong-doer; thus, according to Christian beliefs, Jesus atoned for the sins of all human beings. But a son could also try to atone for his father’s sins.

Importantly, atonement doesn’t require the sinner to address the grievances of the fellow human whom she has wronged. That’s perhaps more obvious in the religious context, because the believer, by perpetrating an injustice against another person, has wronged God. The disconnect between doing wrong and atoning for having done wrong becomes evident when we consider typical acts of atonement, which include acts of repentance and self-punishment — acts that are hardly designed to satisfy a wronged party. From the point of view of the victims, though, a perpetrator’s attempt to atone for her sins could result in satisfaction if it resulted in the perpetrator’s punishment.

Although acts of atonement don’t seem designed to do justice to the victim or to repair a relationship between perpetrator and victim, I suspect in this case Germans are by and large off the hook. Atonement was not something most of them were seeking (certainly not Angela Merkel when she agreed not to close Germany’s borders in 2015) but rather something they have been expected to seek, not least by God-fearing North Americans.

The Auschwitz trial doesn’t feature prominently in Trentmann’s Out of the Darkness. He doesn’t mention the Mulkas. That I thought of Rolf Mulka, the bronze medal winner, when watching the Paris Olympics was because of his father’s reappearance on the big screen.

Mulka senior is one of the protagonists in Die Ermittlung (The Investigation), which recently premiered in German cinemas. The film is based on the controversial play of the same title by German-Swedish writer Peter Weiss. The playwright, who was an observer at the Frankfurt trial, used the proceedings to create an oratorio (without music) in eleven cantos inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy. He condensed the two-year trial into a courtroom drama with eighteen defendants (including Mulka), nine witnesses, a judge, a prosecutor and a defence lawyer. It premiered with the Royal Shakespeare Company in London, only months after the trial’s conclusion, and in fourteen German theatres in the 1965–66 season.

Much like the play, the film, directed by Rolf Peter (“RP”) Kahl, takes place entirely on a stage. In fact, the film resembles the recording of a live performance. It remains close to Weiss’s script, but features thirty-nine witnesses, thereby avoiding the play’s conflation of several witness statements. Despite its format and length — it runs for four hours — I found it enthralling.

The final canto of Die Ermittlung deals with the crematoria in Auschwitz. The prosecutor asks a witness whether Mulka would have been aware of what happened there. In his reply, the witness implicates not just Mulka: every one of the 6000 people who worked in the camp would have known, he says. They all performed their duty, which was indispensable for the functioning of the camp’s machinery.

Rainer Bock as the judge in Die Ermittlung.

The judges in the recent trial against the Stutthof typist thought so, too. However small a role the personnel of the concentration camp played, they were all accessories to murder.

In the play, the witness goes one step further. The railway workers involved in transporting deportees to the camps knew what would happen to them, he claims, as did the public servants in hundreds of offices concerned with the deportations. Challenged by the defence counsel that his statement is informed by hatred, the witness denies he is seeking revenge:

I stand indifferently

before the defendants

and only point out

that they could not

have carried out their job

without the support

of millions of others

Upon visiting Auschwitz shortly after having attended the Frankfurt trial, Peter Weiss wrote in a note, switching from the autobiographical “I” to the third person: “There is nothing he can do here. For a while complete silence reigns. Then he knows it is not over yet.”

If it had been possible to blame only Hitler and his henchmen, including the thousands of Mulkas, for the Holocaust, then their conviction for murder would have signalled that it was over. The fact that there were millions of accomplices and even more bystanders who remained indifferent or averted their eyes ensured that it couldn’t be over, not in 1946 with the conclusion of the first Nuremberg trial, not in 1965 after the sentencing of Robert Mulka and his co-defendants, and not in 2024 when the federal court dismissed the appeal against the conviction of the former typist.

Much has been written about the exceptional nature of the Holocaust, about how it stands out among other genocides. In one of the most disturbing passages of Die Ermittlung, Weiss suggests that Auschwitz was unexceptional — not in the sense that there have been similar sites of mass murder but because aspects of Auschwitz resembled “normal” life outside the barbed wire fence. The playwright lets one of the witnesses say:

We must abandon the lofty attitude

that the universe of this camp is incomprehensible

We all knew the society

from which the regime emerged

that was able to produce such camps

The order that applied here

was familiar to us for its structure

Elements of the order whose structure was familiar to the former camp inmate survived the defeat of Nazi Germany. So did some mental dispositions that upheld that order, inside and outside the camps. Trentmann, privileging Germans’ attempts at coming to terms with the Nazi past, sometimes glossed over the fact that Germans’ indifference towards the plight of others endured well beyond 1945. Peter Weiss and his interpreter RP Kahl didn’t; the play and the film could therefore be taken as unintended but useful rejoinders to Trentmann’s book. •

Out of the Darkness: The Germans 1942–2022

By Frank Trentmann | Allen Lane | £40.00 | 849 pages

Die Ermittlung

Directed by RP Kahl | Film Mischwaren