Few writers have had such chronic health problems as Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894). Much of his childhood was spent in the nursery, confined by illness and his parents’ fears. Having inherited a “weak chest,” all his life he was plagued by violent and bloody coughing fits, probably caused by tuberculosis. Deemed too susceptible to the vagaries of the Edinburgh climate, he was kept from attending school. Small wonder he developed a perfervid imagination. The only available playmate was his adult nurse.

The other constriction was the stifling respectability of his parents. His father came from a line of engineers and was determined that Louis (as Stevenson was habitually called) should enter the family business. He was propelled into studying engineering, and as a default position law, but the lure of taverns and the shady world he had been segregated from came to count for more. Perhaps, in the double life he was leading, lay the seedbed of one of his best novels, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

Part of the originality of Camille Peri’s double biography, A Wilder Shore, is that it starts with the story of Fanny and not Louis: she has been fully wheeled into position when they meet at an artists’ colony in France. And while there have been at least four biographies of Fanny alone, none of them, claims Peri, “has captured the complex and dynamic woman she was, or the passion, companionship and creative energy that became the life force of the Stevenson marriage.”

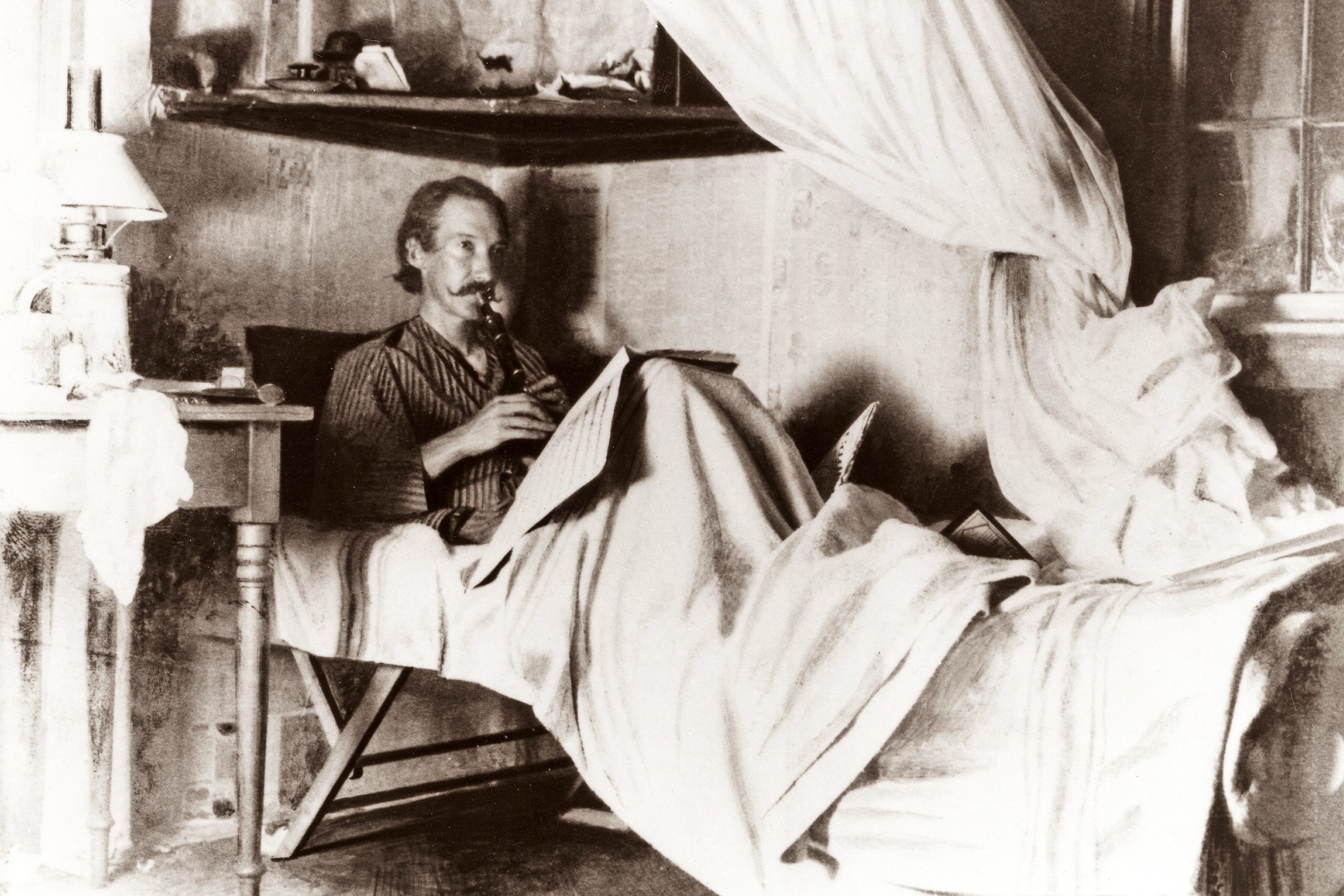

It seems it was love at first sight, and remained passionate. Truly it was an attraction of opposites. She was small, a bundle of energy, pretty, with an olive complexion, enhanced by extravagant jewellery; he extraordinarily thin, likened to a stork — when he pointed it was as if he was throwing his arm away, someone said. As often as not a cigarette would be dangling from the end of it. Quite early Stevenson settled on what would become his bohemian uniform: velvet jacket (always from the same tailors), straw hat and — at a time when men preferred beards — straggly long hair. In Sydney, at the height of his fame, he would be ejected from a posh hotel.

Fanny brought with her two children from a previous marriage, and was a writer herself. Immediately she fell under Stevenson’s spell — repeatedly people commented on his charm, his extraordinary eyes, the rich voice as he freely conversed. Fanny, marked by the recent loss of a five year-old son to tuberculosis, saw that in a way she could make good by caring for Louis. True, she was eleven years older than him, but that followed the pattern of Louis’s attachment to his nurse. She saw, correctly, that in partnership each would be energised, have larger lives. Both were rebels and adventurers. Owing to complications involving Fanny’s first husband, they would not marry for some time. Once Louis had described marriage as “a sort of friendship recognised by the police.” But Fanny was something else: his “teacher, tender, comrade, wife.”

The worldly Fanny — whose short stories would appear in the best American magazines — appreciated Louis’s greater talent. When they met he had only published essays: it was she who prodded him to follow his natural inclination and write fiction. (And to finish what he began.) But her contribution was much greater than that. Louis came to place his work each day by her bedside for criticism and discussion. Fanny told a friend that “Later on, if he works and lives he will get both fame and money, I am sure.” That took some faith: much of Treasure Island was written when Louis was in bed, trying to avert haemorrhaging.

Louis had already demonstrated his commitment by following Fanny back to San Francisco — at some cost to his health. Years before he had told his mother “I shall be a nomad, more or less, until my days are done.” That turned out to be the case. Its first fruit was the two-part book The Amateur Emigrant, in which he described first his journey to New York and then the sequel across America to California. (There he noted the “stoic” response of the Indians, as they watched new settlers pour off the train.) The shipboard section brought him trouble; Stevenson wrote of steerage as he found it, but the publisher objected to the blurring of class boundaries. So the account was bowdlerised, for respectables.

Stevenson was a man very broad in his sympathies, if rather vague about them. He got on to the contemporaneity and importance of American literature quite early. While retaining little of his early socialism, he remained radical by inclination. He described women’s social conduct as “the arts of a civilised slave among good-natured barbarians.” Stevenson also saw British rule in Ireland as being without moral authority, but while he opposed Fenian terrorism he could not quite bring himself to endorse home rule. It was the essence of Ireland he cared about.

Stevenson’s apogee was reached in the mid-1880s, when he published three novels which had phenomenal success. First was Treasure Island (1883) — still popular, if more on screen than from being read. It’s the classic adventure story for boys. But as Peri points out, for young readers it contains an important lesson: “Learn to think for yourself. Don’t accept what adults tell you as the truth.” Kidnapped (1886), an adventure story for teenagers, traces the journey of a man and a boy across Scotland after the 1745 rebellion, as the English move in to occupy the Highlands. The main character, David Balfour, is shown to be learning to develop courage and independence. One of the book’s admirers was Hilary Mantel, who as an eight-year old girl was drawn to it for that very reason. She also admired its style, its velocity, and found herself re-reading it every few years.

The third novel from this period was Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The existence of dissociation identity disorder (split personality) is now well-known. But in those pre-Freudian times a good many readers would have got halfway through the novella before realising respectable Jekyll and criminal Hyde were one and same person. It caused a sensation, and a stage version soon appeared. Scarcely had the run started when the Jack the Ripper killings began: the play was soon withdrawn.

Meanwhile the Stevensons moved about, living in England, France, and then on to America, where Louis was feted to an extraordinary degree. But despite spells in sanitoriums, his illness persisted. Fanny suggested they hire a yacht and go on a cruise to the South Seas. It was to be the first of three. Louis’s health improved immediately — he even took to swimming. On their second cruise they decided they would settle in Samoa.

At Vailima, while never completely well, Stevenson became a kind of patriarch. “I am chief and father” to twelve Samoans, he told an English friend; “my cook comes and asks permission to marry…” Their house (the only double-storeyed one in Samoa) also became a social hub — Louis’s celebrity attracted passing sea captains as well as local dignitaries, white and indigenous. Gradually other members of his family — including drifters and ne’er-do-wells — came and joined Fanny and Louis. There was increasing collaboration with her, this time in publication, and also with other family members, in particular his step-son Lloyd Osbourne.

Louis himself saw the South Seas as a crucible of imperialism, its veritable frontier. Wanting to understand it better, he embarked on a massive two-volume work (of a kind that existed on a number of British colonies) embracing political, cultural, historical and anthropological elements. But he had to abandon it: the project was too far removed from his existing talents. Nevertheless, the basic concern remained: the “extinction” of Pacific Island culture by Western civilisation.

The Germans in particular had penetrated Samoa by establishing plantations, and although the islands remained nominally independent, the three predatory powers — the United States, Britain and Germany — were vying for influence and manipulated different factions. Civil war did break out (rather reluctantly); Stevenson tried to act as a conciliatory influence, to little effect. Letters to the Times on the subject and a short book also occasioned little interest. Samoa — and Stevenson — were so far away, particularly to literary friends. The general feeling was that he had marginalised himself.

Meanwhile Stevenson dabbled in fanciful tales, wrote an undistinguished novel set in the South Seas and also a well-regarded short story set there. But it was Scotland that moved back to occupy pride of place in his imagination. He described how once, as he stood on the veranda at Vailima watching the rain falling down, he suddenly staggered as memories crowded in of Highland huts and peat smoke, wet clothes and whisky. The essence of Scotland — and again he was drawn to the eighteenth century, the period when England tightened her screws on the country. Stevenson wrote a sequel to Kidnapped, Catriona, which lacked the drive of the earlier novel, and contains dull expository passages about Scottish nationalism and English oppression. Samoa had sharpened his vision: the exploitation of the indigenous and the rapacity of newcomers were now all around him.

Death overtook the writing of Stevenson’s last novel Weir of Hermiston (another Scottish one). He was only forty-four. The torso, when published, drew considerable praise, although more in America than in England. Some say that, had it been completed, it would have been his masterpiece. It was only at the end, Graham Greene would write, that Stevenson’s “dandified talent began to shed its disguising graces, the granite to show through.”

What is plain is that the decline in Stevenson’s reputation — something he feared — began very soon after. While he had always enjoyed the approval and warm friendship of Henry James, writers such as H.G. Wells, Virginia Woolf and Joseph Conrad — whose Heart of Darkness followed the path signposted by Stevenson’s Ebb Tide — were dismissive.

One of the virtues of A Wider Shore is that Peri shows the compensating influence Stevenson has had in popular culture. There have been no less than sixty screen adaptations of Jekyll and Hyde (excluding porn). And Kidnapped, says Peri, helped establish the genre of the “epic buddy road trip,” extending to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider. John Lennon said Kidnapped “opened my whole being.”

Written in a highly readable style, A Wilder Shore is backed by solid research. Camille Peri’s is an engrossing account of the Stevensons, psychologically acute, and one that does much to counter the dismissive “writer’s wife” stereotype imposed upon Fanny. •

A Wilder Shore: The Romantic Odyssey of Fanny and Robert Louis Stevenson

By Camille Peri | Viking | $69.99 | 464 pages