French impressionism has been the cultural wallpaper of my life ever since, as a teenager, I first encountered Georges Seurat’s La Grande Jatte — all six square metres of it — at the Art Institute of Chicago. It was the jewel in the crown of the museum’s vast collection of impressionist and post-impressionist art, courtesy of lavish bequests from the city’s haute bourgeoisie.

Six decades later the movement’s vision, impact and mystique remain as potent as ever, the subject of myriad monographs, blockbuster exhibitions and record-breaking auction sales. So is there really anything new to say about its iconic artists and their endlessly reproduced works?

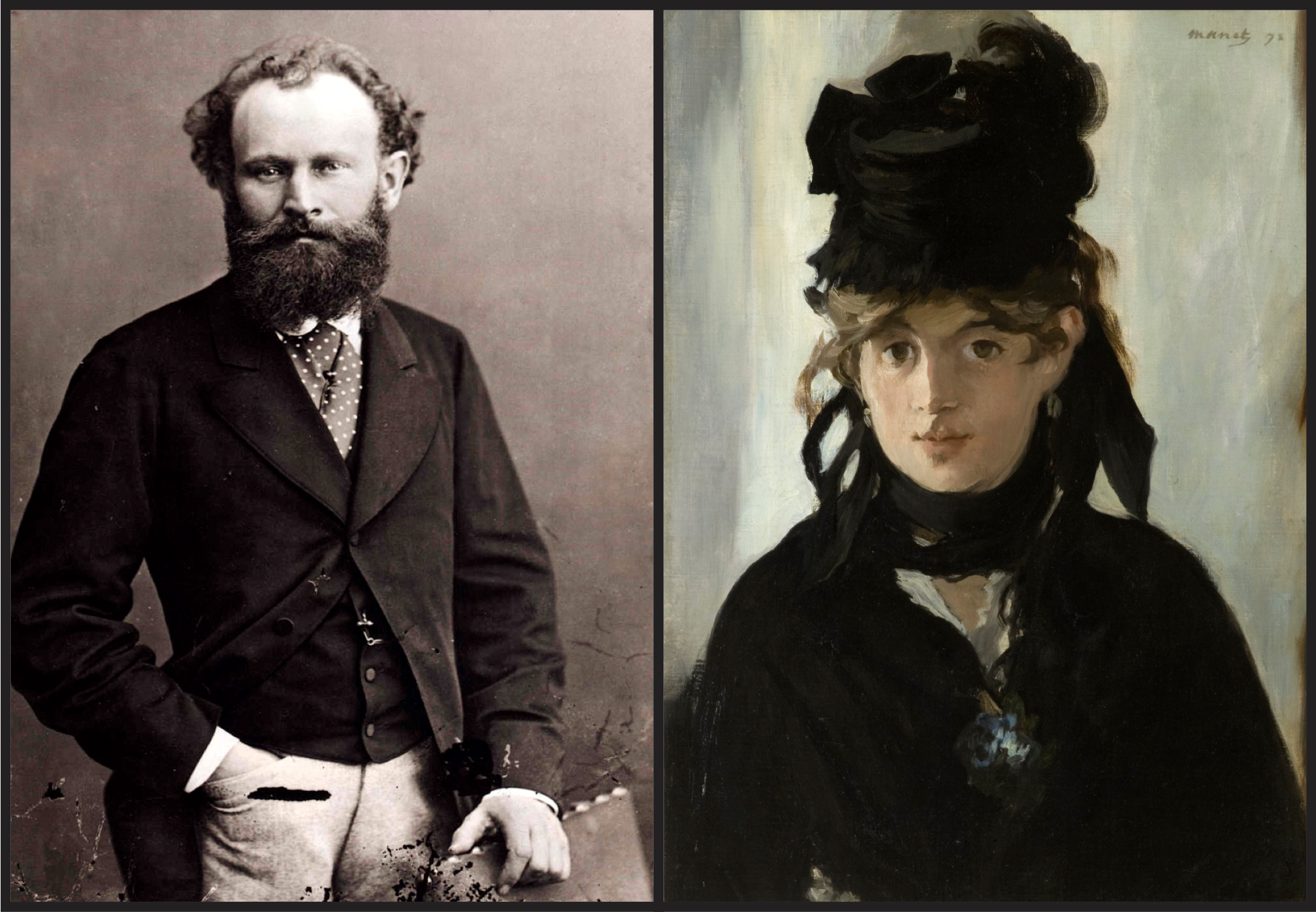

Sebastian Smee, the Pulitzer Prize–winning Australian-born art critic of the Washington Post believes there is. His Paris in Ruins: Love, War, and the Birth of Impressionism is “premised on the conviction that we cannot see impressionism clearly” without grasping the impact on the movement’s leading painters of the Franco-Prussian War and the ensuing French civil war of 1870–71. He anchors his argument in “an affair of the heart between two great artists,” Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot, whose lives and careers were upended by the trauma of those twin cataclysms before emerging triumphant in the following decade. It’s an arresting tale of how their radical art and republican politics evolved both before and after the “Terrible Year.”

Smee’s effort “to knit together art history, biography, and military and social history” relies on an impressive list of well-known sources in all these fields. He particularly acknowledges Alistair Horne’s The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870–71, which his father recommended to him three decades ago, as an “essential resource.” While Paris in Ruins is not based on original research, Smee brings to his task a wonderful eye and an engaging style that results in many insightful readings of the art he uses to illustrate the main points of his narrative.

Half of this book is devoted to the ten months that elapsed between the onset of France’s war with Prussia and the fall of the Paris Commune. Close to 140,000 French (mainly working class) troops died fighting the Germans. Large parts of Paris lay in ruins thanks to the unprecedented bombardment of civilians in its main arrondissements. (Manet and Morisot remained in the city throughout this period — he while serving in the National Guard and she staying with her parents out of harm’s way.) Meanwhile, in Montmartre and Belleville, the slaughter of 20,000 communards by government troops would not soon be forgotten.

Even more long-lasting was the pain of Germany’s humiliating peace terms, which included the loss of Alsace and Lorraine, five billion francs in reparations, and a German victory parade through Paris. Here the seeds were sown of a seventy-year cycle of conflict between France and Germany that would culminate in two world wars.

Set against so much present (and future) pain, the bright side of the “Terrible Year” for Manet and his followers was that it abruptly ended the despised Second Empire of Lous Napoleon III by ushering in the Third Republic. Within a decade the government was being led by moderate republican politicians who had gathered before the war with these artists in their favourite cafes and salons, dreaming of Napoleon’s (and the reactionary art establishment’s) downfall.

By 1880 these artists’ work had also become much more in tune with the times. The rules of the annual Salon — that powerful bastion of artistic conservatism that had rejected so many of the works of the “new painters” — were soon loosened, thereby increasing the new generation’s exposure and enhancing their reputations. Even more importantly, the market for their paintings was expanding through the rise of independent dealers, prestige auction houses and the interest of overseas buyers (cue Chicago).

The inflection point for their rising fortunes was the 1874 Société Anonym group exhibition, where Morisot, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Renoir and Cezanne supplied a quarter of the works. While reactionary critics identified these artists as de facto “communards,” it was the epithet of “impressionists” that endured. Underlying their new appeal — in the wake of so much carnage and heartache — was the balm their decidedly vibrant, unheroic depictions of sunlit landscapes, simple pleasures and bourgeois domesticity offered to those who could afford to buy them.

The Terrible Year also marked a watershed in the life and art of Berthe Morisot, who had just reached the grand old age of thirty. During the 1860s she and her sister Edma had both showed promise as painters, exhibiting several times at the Salon. But the combination of bourgeois pressures favouring marriage over career and the substantial barriers placed in the way of women artists pulled the sisters in different directions.

While Edma soon married and stopped painting, Berthe held out for an artist’s life despite her own rising doubts about her talent and career prospects. As her mental and physical health rapidly declined during the siege of Paris and then the Commune, she steeled herself by declaring to her sister that “work is [now] the sole purpose of my life.”

Morisot never looked back. She dedicated her artistic practice to what she knew best, the world of women, children and bourgeois domesticity — often shown at a threshold looking out to what lies ahead and beyond — painted with increasingly loose and confident brushstrokes that pushed the boundaries of impressionism. She earned the respect of her peers (especially Degas), the increasing approval of critics and a steady stream of sales guaranteeing her financial independence. Most notably, she was the only woman artist represented in the breakthrough 1874 exhibition. In Smee’s view, Morisot “would go on to be regarded as the most groundbreaking female artist of the nineteenth century.”

What the fall of the Commune and the early years of the Third Republic exposed, in Manet’s case, was both an ongoing anxiety about securing public recognition for his work and the brittle nature of his republicanism. He refused to associate himself with the first “impressionist” exhibition, for example, which showcased the work of all his notable followers. Indeed he did his best to dissuade Morisot from exhibiting there too. Why? Because “Édouard was convinced that in setting up an alternative exhibition, the breakaway artists were denying themselves the Salon’s enormous audience and therefore a chance to capitalise on recent gains.”

Manet was clearly still hanging out for greater recognition from the Salon jury, which eventually did come his way. Then, in 1880, the republican government made him a chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, confirming the importance of his services to art as well as to the cause of (moderate) republicanism.

Manet’s hunger for state honours stood in contrast to Gustave Courbet’s refusal of them. Just before the war the older Courbet (the great champion of “realism” and a committed anarchist) had turned down an offer of the same “monarchical order” because “when the state presumes to give out awards… it is usurping the public’s taste. Its intervention is… fatal to the artist, who it misleads as to his worth, [and] fatal to art,… which it condemns to the most sterile mediocrity.” As Smee notes, “Manet’s young followers couldn’t have put it better.”

But even more profound political differences between the two artists would emerge during the Commune, when Courbet was charged with protecting the nation’s artworks while calling for the demolition of the Vendôme Column, a hated symbol of Napoleonic rule. Following the Commune’s defeat, he was sentenced as a prominent communard to spend nine months in prison before being forced into exile. Far from leaping to Courbet’s defence, Manet would go on to condemn the old master as one of the radicals who “had put the whole idea of a true republic in grave jeopardy” and so was “not worthy now of the least interest.” Given that Courbet’s realism had paved the way for Manet — who aspired to become the Courbet of his generation — these sentiments exposed the limits and self-serving nature of the younger man’s political worldview.

Nevertheless, while far from being a political radical, Manet was undoubtedly a revolutionary artist. Recognised in his time by the likes of Baudelaire and Zola as the trail-breaking “painter of modern life,” he brought Courbet’s realist perspective on provincial life to bear not just on the urbanity and spectacle of contemporary Paris but also on the manifestly inadequate modes and subjects of representation that dominated the Salon. His breakthrough works in the 1860s (especially Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia) simultaneously subverted the tastes and traditions of the art establishment while shining a dark and searching light on the underbelly of Parisian modernity.

Manet’s charisma as well as his art attracted many talented followers, notably Monet and Renoir, who then began experimenting with styles and techniques that eventually came to underpin the impressionist movement. In the wake of the Terrible Year, Manet assimilated some of these technical breakthroughs into his own work, but (like Degas) he retained his attachment to realism, culminating in his brilliantly enigmatic A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

So, yes, the events of 1870–71 certainly did impact the life and art of the French impressionists, not least Manet and Morisot. But, as Tina Turner might ask, “What’s love got to do with it?” Was there an “affair of the heart” between Berthe and Édouard, and, if so, what difference did it make to them before and after the Terrible Year? Smee draws mainly on Berthe’s correspondence with her sister and the many portraits she sat for Manet to suggest that they were (at least for a time) “deeply in love.”

What Smee succeeds in demonstrating is that Berthe’s relationship with Manet was always going to be a liaison dangereux. For starters Manet had lived since 1851 with the woman he eventually married, whose son (of uncertain paternity) he never legitimated. Édouard was also a serious flirt who made a habit of choosing as his models professional women artists (both before and after meeting Berthe). On first meeting the Morisot sisters, he mischievously hoped they would influence members of the Salon jury by marrying them.

While Berthe sat often for Manet, he never portrayed her as a working artist but simply as an attractive subject. Indeed, she first appeared in his On the Balcony, a work inspired by a Goya painting of two courtesans. Perhaps most dangerous of all, Manet’s artistic stature was bound to threaten Morisot’s self-confidence about her own work. For example, the freedom with which he overpainted one of her artworks — without her permission — on the eve of its (successful) submission to the 1870 Salon could not have been more undermining.

However, as we have seen, the Terrible Year had a galvanising effect on Morisot’s resolve to pursue her artistic career. It therefore also marked a watershed in her relationship with Manet, as evidenced by her decision — against his advice — to show her works at the first impressionist exhibition. While she may have once wanted some kind of closer relationship with Édouard, what she now needed was someone far less threatening and more reliable who would give her the space to grow as an artist. As it happens, she found in Manet’s younger brother Eugéne a husband who would prove to be a perfect companion. Soon after their marriage she also gave birth to a beautiful daughter who would become the subject of some of her finest paintings.

My admiration for Paris in Ruins comes with two important caveats. I found Smee’s treatment of the Terrible Year to be unnecessarily one-sided. He partly blames his privileging of well-to-do bourgeois views over the sentiments of the labouring classes on the fact that the former are so much better documented than the latter. True, but as he notes of Morisot’s recommitment to her art during this period, “people emerging from trauma, or from prolonged periods of crisis… are often ready to make great changes. Their experiences have given them a profoundly altered idea of what is at stake in their lives.”

Had Smee attempted to apply the same perspective to the desperate, angry and impoverished residents of Belleville and Montmartre — before as well as during the events of 1870–71 — he might have better imagined why they were prepared to vote and fight for the Commune, despite the shortcomings of its leaders and the overwhelming odds against them. Instead, he sometimes resorts to his own patronising asides about the communards that simply echo Manet’s views — if not the reactionary opinions of conservatives like Edmond de Goncourt and government supporters such as Cornélie Morisot, Berthe’s mother.

My other reservation is that I wish Smee had played more to his long suit as a gifted interpreter of pictures with an uncanny ability to extract from them new insights into the lives and thoughts of his principal subjects. As an example, here is just a short excerpt from his extended description of Manet’s Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets:

Where the light in most of Manet’s portraits is frontal and bleaching, flattening his subjects’ features, here the light comes in from one side. Berthe’s dark eyes are boldly enlarged, amplifying the erotic challenge of her gaze. Her face expresses rapt, appraising attentiveness to the man portraying her, as if the two were in the midst of a lively conversation. We see the very beginning of a smile, inflected by the lightest touch of irony…

Unfortunately, the reproduction of this work in Paris in Ruins is not much bigger than a postage stamp, making it impossible to appreciate the justice of Smee’s commentary. (Having reviewed Manet’s portraits of Berthe, I am certain that not all of them reveal her to be “deeply in love” with him — and vice versa.)

This defect is made even worse when there are no reproductions at all of most of the other artworks he discusses. In other words, we are deprived of the visual evidence that is so important to Smee’s larger arguments. For a few dollars more, a larger format graced by far more pictures would have greatly enhanced the power and pleasure of this important work.

One-hundred-fifty years on from its staging, the first impressionist exhibition is still reverberating through the art histories of Europe, North America and Australia. Despite variations in its transnational reincarnations, impressionism continues to beguile and mystify art lovers, despite (or because) of the dissonance between the brightness of its images and the darkness of so much that surrounds and threatens us today. As I’ve previously suggested in these pages, it’s time to start new conversations about the historic nature and continuing relevance of impressionism, as well as taking up the one initiated by Smee in Paris in Ruins.

Meanwhile, even now, I must confess I’d happily return to Chicago to spend once again a “Sunday afternoon in the park with George,” rapt/wrapped in the uncanny stillness of Seurat’s La Grande Jatte. •

Paris in Ruins: Love, War, and the Birth of Impressionism

By Sebastian Smee | Text Publishing | $36.99 | 416 pages