The fascinating story of how two new books — Sandhill Girl and Enlightened Aboriginal Futures — came into being centres on three people: the Lutheran missionary F.W. Albrecht, his former student Lorna Wilson, and Lorna’s son Barry.

Albrecht, who had come to Australia in 1925, worked in Mparntwe/Alice Springs in the 1950s. There he established an enlightened and culturally sensitive education scheme for Aboriginal students that ran counter to prevailing stolen-generation practices.

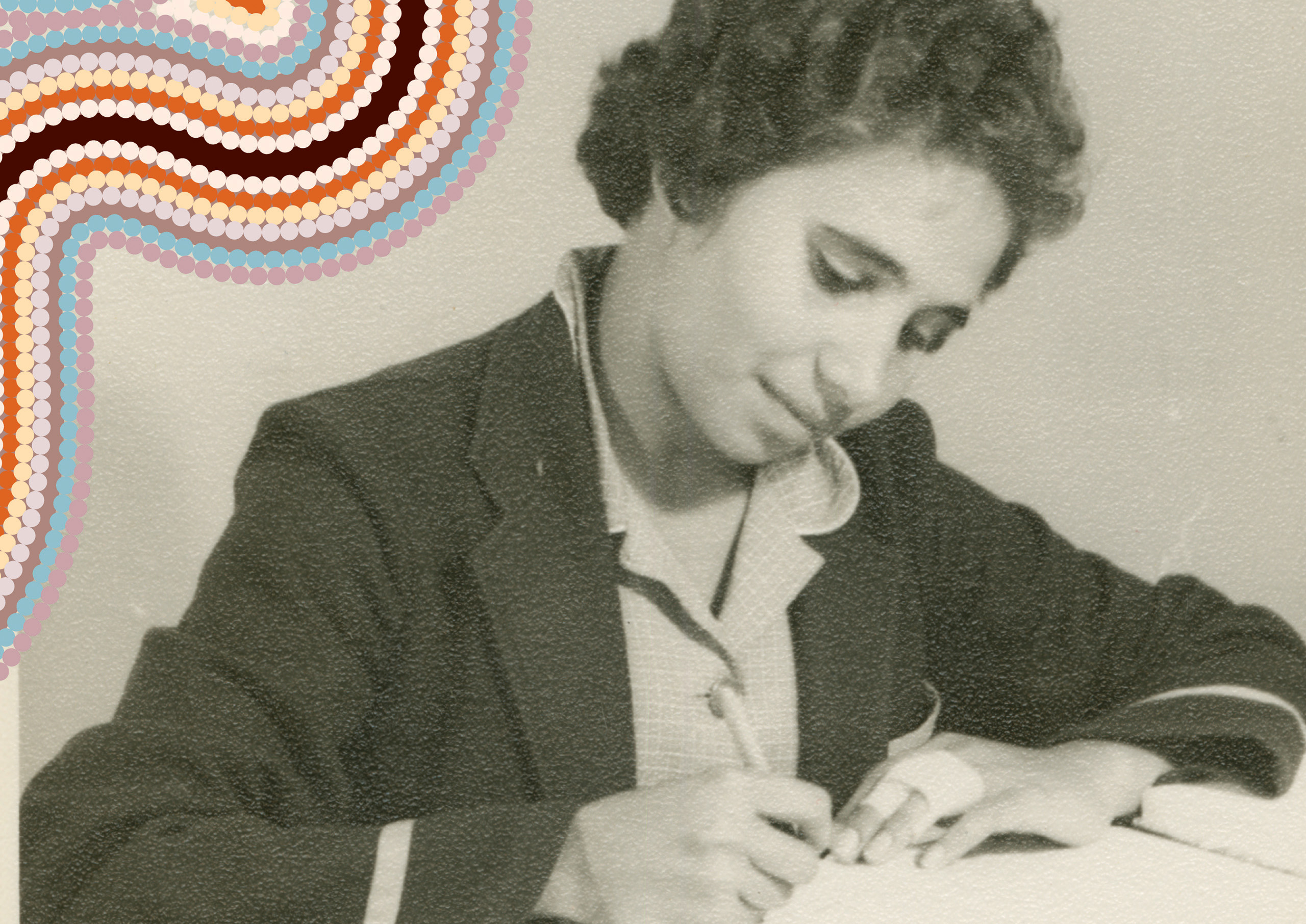

Lorna was one of the first students in the scheme, and Sandhill Girl is her memoir of growing up and obtaining an education west of Mparntwe/Alice Springs. “I wanted to learn,” she declares. In 1968 she gave birth to a son, Barry, and passed on to him her passion for education. Today Barry is a leading scholar in Australian Indigenous studies and deputy vice-chancellor (Indigenous) at the University of Melbourne. Together with the historian Katherine Ellinghaus, he examines Albrecht’s education scheme in Enlightened Aboriginal Futures, closing the loop back to the missionary.

This is living history: the educational lineage of Albrecht, Wilson and Judd unfolds before our eyes, bringing the past alive through a direct connection to the present. Sandhill Girl is for readers of all ages and is richly illustrated with photographs that add to the immediacy of the past. Enlightened Aboriginal Futures, an academic work, is written in an accessible, succinct style and runs to barely more than a hundred pages.

Together the books give us a vivid picture of Albrecht, often seen as a somewhat stolid “straight-out man” (to quote the title of Barbara Henson’s 1992 biography). They reveal the nuances of his strait-laced persona and show him negotiating complex cultural terrain. Judd and Ellinghaus put Albrecht’s education scheme in a broad historical and cultural context in order to “shift focus on Enlightenment thinking from Europe to Australia.”

Friedrich Wilhelm Albrecht was born on 15 October 1894 and grew up in the village of Kroczyn in eastern Poland, then under Russian control. His parents were among a group of farmers from Prussia who had moved east when large Polish landholders were stripped of their estates and smallholdings offered to Prussian settlers. The eldest of eight children, Albrecht was named after King Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia.

The small Prussian outpost was united by language and religion. Albrecht dedicated himself to a religious life at an early age, and in 1913 moved to train at the Lutheran Mission Institute at Hermannsburg, near Hanover in Germany. Mission institutes like this one catered to students from poor backgrounds because they provided meals and accommodation.

Albrecht’s training was interrupted by the first world war. With a fall as an infant having left him with a crippled leg, he served in the German medical corps rather than the regular army. His family and other Prussian settlers, meanwhile, were deported to Siberia because they had come to be perceived as a threat by the Russian authorities. Most of the Albrecht children — five within a month — died of cholera in Siberia’s dreadful conditions, and Albrecht, too, contracted the disease and barely survived.

After the aspiring paster completed his training in 1922, he was invited to become the missionary at the Finke River Mission in Hermannsburg/Ntaria in Central Australia. The mission board had put out seven unsuccessful calls to fill the post, but prospective candidates had been deterred by its remoteness and the lack of medical facilities.

Since the mission had been established in 1877, its pastors had engaged with Indigenous languages and cultures alongside their Christianising mission. They had established the first school in the Northern Territory at Hermannsburg/Ntaria and taught children in English and Aranda. Religious services too were bilingual.

Albrecht’s predecessor, Carl Strehlow, had served as pastor from 1894 until 1922. He attained an understanding unparalleled among Europeans of the language and culture of the Aranda and Luritja people, as recorded in his monumental work Die Aranda- und Loritja-Stämme in Zentral-Australien (The Aranda and Luritja Clans of Central Australia), published between 1907 and 1920. He died in 1922 on an excruciating quest for medical treatment recounted years later by his son T.G.H. Strehlow in the epic Journey to Horseshoe Bend. True to the missionary approach, the book draws on Aranda language and knowledge of Country alongside German Lutheranism and classical literature.

Albrecht would stay on as a pastor in Central Australia for nearly forty years until 1962, when he retired to Adelaide. Two main projects exemplify his work.

The first belonged to his time at Hermannsburg/Ntaria. When he arrived in 1926 he confronted a drought and a grave scurvy problem that was causing abominably high child mortality among the Aranda people at the mission. The introduction of sheep, cattle and goats had ravaged traditional plant-based food sources but insufficient water was available to grow fruit and vegetables.

Over the next decade Albrecht pursued plans to build a pipeline from a reliable water source at Kuprilya (or Kaporilja) Springs to a large new holding tank at the mission. Using funds from donors in the southern states, the project was eventually opened on 30 September 1935 to great celebration underpinned by the religious connotations of water flowing in the desert. With reliable water now available to grow fruit and vegetables, the child mortality rate dropped significantly. The tank can still be seen today and the pipeline project lives on in local memory; every year in Ntaria, the first Sunday in October is Kuprilya Day.

The second project, studied for the first time by Judd and Ellinghaus, was Albrecht’s educational scheme, developed after 1952 when his wife Minna’s health problems forced the family to move to Mparntwe/Alice Springs. Albrecht continued his work as pastor and spent hours bringing in and arranging for children from surrounding stations and settlements to attend primary school in the town.

He soon became concerned that this schooling didn’t set children up well for life. With no high school in the town, primary school led neither to employment nor to further schooling or training, leaving young students in limbo. Albrecht’s scheme involved young Indigenous students moving south to live with hosts from Lutheran congregations and attend local state schools followed by Lutheran secondary schools.

Judd and Ellinghaus adduce strong evidence to show that, in contrast to stolen-generation practices, the scheme was informed by energetic input from Indigenous people and responded to their desire for further education. While recognising the contested nature of consent when a power imbalance exists, they show that agreement from the students and their families was integral to the scheme.

Because girls — Lorna Wilson among them — stood out at primary school and were encouraged by their families to continue their education, they came to be focus of the program. “Leaving was my choice,” she writes, but difficult the decision was bolstered by her elder brother. “My brother said, ‘You go and learn, go and learn… It will be good for you to learn another culture. You go and learn.’ I listened to my brother because I looked up to him.”

In 1959, aged twelve, Lorna went to live for two years with a host family in the South Australian town of Moculta, where she attended school. Albrecht knew that it would be challenging step for her. His eldest daughter, Helene, had found the move from Hermannsburg to boarding school a bewildering shock when she was sixteen. Lorna faced an even more formidable learning curve. Albrecht knew it was important to keep up contact and encouragement throughout her time in Moculta.

At the end of 1961 Lorna returned to Alice Springs School. Then, aged sixteen, she boarded for a time at St Paul’s College in Walla Walla, near Albury, before moving into nurse training at Wodonga Hospital. It was a testing and previously uncharted road to independence and employment.

Rather than expunging their Indigenous culture, Albrecht’s scheme encouraged students to keep connected to their homes, language and culture and provided ways and means to achieve that. It enabled students to withdraw at any time and to return home for the long summer holidays, and encouraged communication among the students themselves and with home base in Central Australia. “Pastor Albrecht made sure that I never lost contact with my family,” Lorna writes. “I always came back to my family.” Later in life she worked as a translator and interpreter of the central and western desert languages Pitjantjatjara and Luritja. This was a great advance on what had earlier troubled Albrecht about schooling for Aboriginal students: “They have lost their past, but not gained the future.”

The metaphor that dominates Albrecht’s scheme and Lorna’s memoirs is opening doors. Host families opened their doors to the students. Education then opened up opportunities for the students without closing them on their cultural background. Albrecht “opened doors and I went through them,” writes Lorna. “I feel like I’m richer for it, because I haven’t lost my culture in the process of doing that — with his help. He was a kind old man.” As an early participant in the scheme and one of the first three Aboriginal students at St Paul’s College, she proudly states, “we opened that door for other Aboriginal kids.”

That the scheme encouraged students to retain their home links primarily reflected Albrecht’s experience of observing the importance to students of their language, family and cultural identity. But it also reflected his personal history and his own cultural background. As a German immigrant in mid-century Australia he had clung to his first language and his culture in an atmosphere of wartime and postwar anti-German antagonism. His childhood memories of his family’s deportation and dispossession would have steeled his views.

His stance was also true to the Lutherans’ commitment to vernacular languages and their central role in forming cultural identity —a commitment articulated by the Enlightenment philosopher and Lutheran pastor Johann Gottfried von Herder, a central figure in German cultural history whose ideas about culture and language strongly influenced Lutheran missionary teaching.

It may strike readers as strange to find the Enlightenment and missionary values mentioned in one breath because they are accustomed to associate the Enlightenment with antagonism towards religion, but the German tradition sees strong continuity between the two. As that acute observer Heinrich Heine wrote, the philosophical revolution of the German Enlightenment emerged from the religious revolution sparked by Martin Luther.

Recognising this, Judd and Ellinghaus place Albrecht’s work in a historical lineage running from Luther in the sixteenth century to the German Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, the incorporation of Enlightenment values into Lutheran teaching in the nineteenth century and their transmission to Australia by the missionaries at Hermannsburg/Ntaria in the twentieth. They show how Albrecht’s educational ideals carried forward Enlightenment values of cultural identity, progress, autonomy and self-responsibility.

This broad historical sweep underpins the powerful cultural perspective Judd and Ellinghaus bring to bear in their book. They contrast Albrecht’s approach with the Social Darwinism underpinning British and Australian government policies towards Indigenous people since colonisation and the stolen-generation practices of the time. Against the view of Aboriginal people as a doomed and dying race, Albrecht envisioned enlightened Aboriginal futures.

By showing Enlightenment ideals in action Judd and Ellinghaus make good on their promise to shift the focus on Enlightenment thinking from Europe to Australia. As they write, “The story of F.W. Albrecht… provides an exemplary case study of how the central ideas of the Enlightenment became known to the Aboriginal peoples of the central and western desert regions and how they often responded positively to the ideas that Albrecht had brought with him from far away Germany.”

True to the German philosophical framework in focus here, Albrecht was more forthright in advocating for language and culture than in promoting political rights. But Judd and Ellinghaus show that his educational scheme did lead him to take issue with government policies. By mid 1959 his work was considered to have veered so far from the government line that the territories minister Paul Hasluck referred in correspondence the “concern that is felt in Canberra.” For Judd and Ellinghaus, Albrecht’s commitment to education became a political stance: “Albrecht can be seen as a true ‘Enlightener’… who sought not just to understand the world through reason but to change it.”

After small-scale beginnings, Albrecht’s educational scheme continued for many years, though with records scattered the total number of students is unknown. After retiring to Adelaide in 1962 Albrecht continued pastoral work and his son, Paul, served as field superintendent of the Finke River Mission until 1983. The Mission returned to Indigenous ownership in the 1980s.

Beyond numbers, Judd and Ellinghaus emphasise the enormous impact of Albrecht’s scheme on those involved and connected with them. They point to the scheme’s importance in educating a cohort of bilingual, bicultural Indigenous community leaders. They also point to Albrecht’s living legacy and the esteem with which he is regarded in Central Australia.

Like Carl Strehlow, Albrecht was honoured by the Aranda people as Ingkarta, meaning a respected and trusted leader and a man with deep knowledge of spiritual matters. In the world of letters, Strehlow — a brilliant and ambitious intellect — is the better known of the two and the subject of thousands of pages of writing. In Central Australia, by contrast, as Judd and Ellinghaus point out, it is Albrecht’s living legacy that continues to be felt and celebrated, both through Kuprilya Day and in his contribution to Aboriginal education and employment. Deep connections persist between his descendants and the people of Central Australia and their networks, as became evident at launch events for the two books, where Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups united to remember the occurrences covered in the books. (Recordings of some of these events can be found on the internet by searching the book titles.)

These two closely related books leave us with a fascinating and multifaceted picture of this “straight-out man.” From Lorna Wilson we get personal memories of a kind grandfatherly figure. From Judd and Ellinghaus we get an analysis of the transplantation to Australia of Albrecht’s cultural background and the transformation of his beliefs into a steely resolve in the face of harsh tests.

Not only do the books give expression to an educational lineage that began with the Enlightenment, but they also provide a vivid picture of Albrecht’s journey and the significant impact he made here. As a migrant and a missionary he brought a foreign cultural framework to mid-twentieth-century Australia that resonated with the people he encountered and worked with in Central Australia. •

Enlightened Aboriginal Futures

By Barry Judd and Katherine Ellinghaus | Routledge | $84 | 112 pages

Sandhill Girl

Lorna Wilson | LWBJKE Books | $39.95 | 71 pages | Available from lwbjkebooks@gmail.com