Clare Wight’s latest book, Näku Dhäruk: The Bark Petitions, is the third volume of her history of Australian democracy. The Forgotten Rebels of Eureka, which came first, centred on the women and men who made and followed the Eureka flag, and You Daughters of Freedom was an account of the Australian suffragists, their victories at home and their impact internationally, symbolised by the Women’s Banner.

Näku Dhäruk is subtitled “How the People of Yirrkala Changed the Course of Australian Democracy.” This is the same claim Wright made for the Eureka rebels and the Australian suffragists, but it seems to me that in this case the historian’s achievement is more significant. The previous volumes followed — or deliberately diverged from — well-worn paths laid down by other historians. Here Wright is creating an entirely new narrative, a reading of Australian history grounded in her own experience, a story only she is qualified to tell. It is a powerful account, and a weighty one, more than 600 pages long.

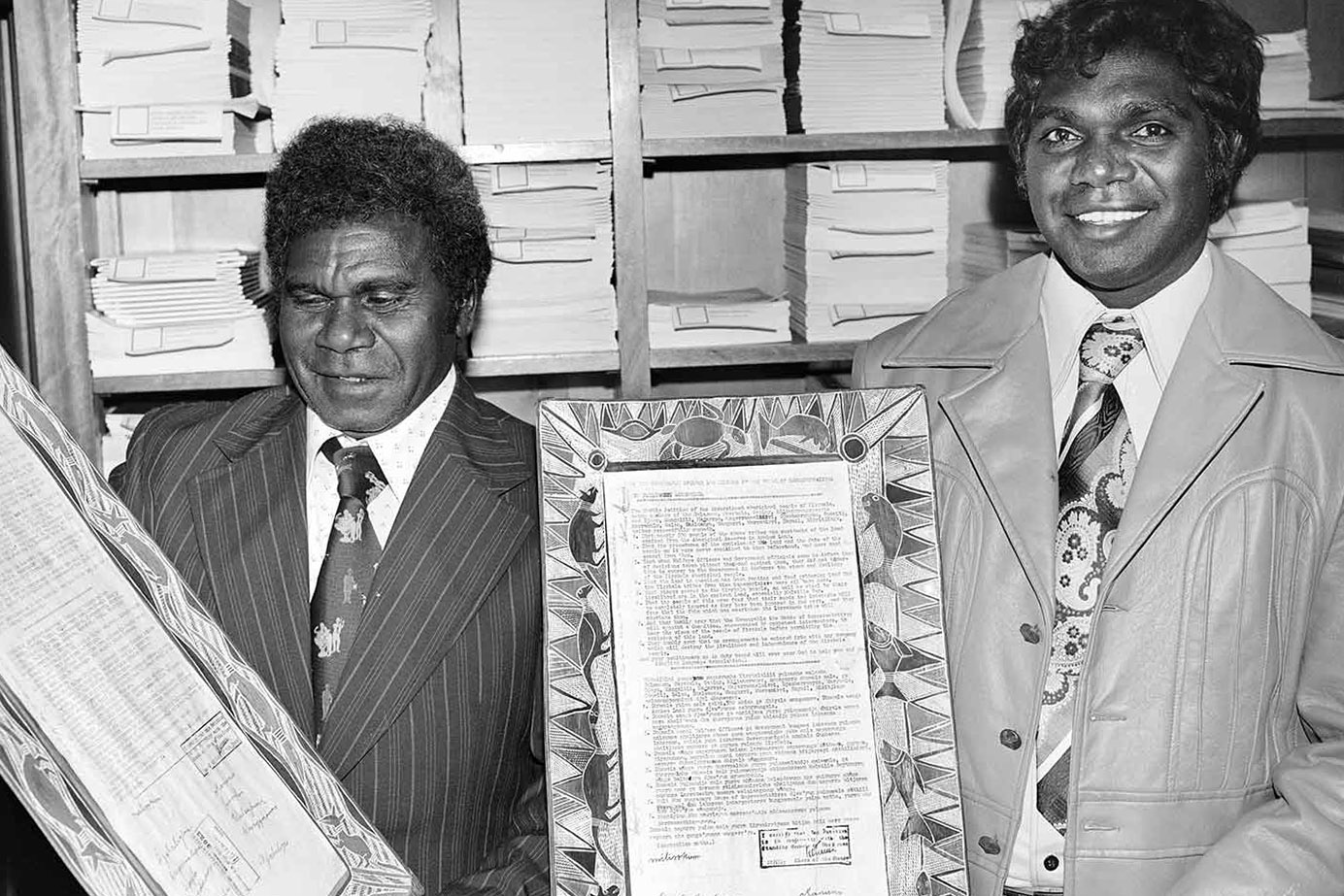

Yirrkala is on the Gove Peninsula in far North Arnhem Land. It is the home of the Yolngu people, the Yirritja and Dhuwa, and the site of the Yirkalla Methodist mission. In July 1963 the community sent to federal parliament a set of bark petitions in the Yolngu language, with an English translation, typed on paper pasted onto stringy-bark panels and framed by cross-hatching and images of land and sea creatures.

“The Humble Petition of the Undersigned Aboriginal People… respectfully showeth…,” the petition began, and went on to ask parliament to recognise the land rights and sacred places of the Yolngu people and prevent the destruction of their livelihood and independence by the incursion of mining.

Wright tells us that the petitions are recognised in current accounts of Australian history as the first of a “cascade of civil- and lands-right-related events” from Wave Hill and the Gurindji to Mabo. The exhibition of one of the petitions in parliament’s Members Gallery suggests recognition of “high-order nation-building.” But Wright is arguing for more than this: the petitions, she says, are “a record of legal intent and sovereign will.” They “conceivably unsettle Western timescales of progress, suggesting the pre-existence of sophisticated systems of government on the Australian continent prior to European settlement.”

Wright makes this case by telling in fine detail what happened at Yirkalla in 1963. Events are described month by month, often day by day. The narrative is driven by the words and actions of twenty-four Yolngu men and women and eleven men and women from the mission.

The story begins in December 1962 with the discovery by Yolngu people of a line of white marker pegs across the paddock where they grew peanuts: pegs placed by mining surveyors. January saw campfire meetings to discuss this and other incursions, and — apparently unrelated — a decision by senior Yirritja and Dhuwa men to authorise the painting of two panels to frame the altar of the new mission church, panels illustrating the creation stories of the two clans.

In May the elders asked for a meeting with the mining men, a meeting that produced no useful results. In July the elders authorised the preparation of the Bark Petitions and their signature by representative and literate Yolngu. In August, when those signatories were challenged because of their youth, the elders signed another version of the petition with thumb-prints. In September the petition was accepted by parliament and in October a parliamentary committee visited Yirrkala to consult with the Yolngu people.

Thus far was a victory. Then the federal election in November saw the Menzies government back in power with a much increased majority and any gains for the Yolngu washed away in the political flood. Disaster was compounded in December by the dismissal of the minister in charge of the mission, Reverend Edgar Wells, as punishment for his support of Yolngu independence.

But other gains across the year were not so easily diminished. An exhibition of Yolngu bark paintings in New York raised press interest in America and Australia, and Yolngu artists featured in Australian magazines and news films. A widely reported performance by Yolngu dancers for the Queen in Darwin led to the formation of a troupe — all authorised by the elders — and a tour of theatres in Sydney and Melbourne organised by the Elizabethan Trust.

The effect, according to the Sydney Morning Herald, was to “increase theatregoers’ respect for forms of music, dance and mime that have existed in this country since the time of Europe’s own pre-history.” The year 1963 made the people of Yirrkala politically and culturally visible and in a sense understandable to white Australians. The effects of this still resonate today.

Only Wright could tell this story. In 2010 Galarrwuy Yunupingu invited Wright’s husband, a furniture-maker, to come to Yirrkala to see whether the wood of the stringybark tree could be used to make fine furniture. Wright and their three young children accompanied him. Wright learned to speak some Yolngu language, and was adopted as a sister by Galarrwuy’s wife Valerie, giving her “a place in the complex web of Yolngu kinship relationships.”

A decade later, authorised by Galarrwuy, she set out to research the story of the petitions: “the oral testimonies” that were “its skeleton” and the “colonial collections” that were its “archival flesh.” Beyond the official archives she discovered family collections of letters and diaries kept by people from the mission, and written versions of Yolngu song cycles describing — recreating — the land and the sea and the seasons. The voices of the missionaries give her account plot and drama; the Yolngu voices seem to speak for the land itself.

Wright concludes her account with the story of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which echoes the Näku Dhäruk in form and intent. As an artefact, an artwork, it is a written text framed by signatures and illustrations of the creation stories of the local Anangu people. In intent it is an invitation to listen to another culture’s truths, something the non-Indigenous Australian community has not yet learned to do. The reader of Wright’s book goes some way towards taking up this invitation.

Wright loops her conclusion back to her democratic trilogy: the Eureka Flag, the Women’s Banner and the Bark Petitions. I wonder if this does full justice to the significance of the petitions. As she says, Yolngu society was never a democracy. “Government was for the people, but Yolngu society was also a patrilineal gerontocracy.” Rather than a moment in the making of Australian democracy, 1963 in Yirrkala is best understood within the national story as an act of statesmanship, an attempt at diplomacy between two nations. To grasp this is to fundamentally rewrite Australian national history. •

Näku Dhäruk: The Bark Petitions

By Clare Wright | Text Publishing | $45 | 640 pages