In June 1934, at home on Moscow’s Volkonskaya Street, Boris Pasternak received a fateful phone call from the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin. “What do you think of Mandelstam?,” Stalin asked the poet. “What are they saying in your literary circles about the arrest?”

Only a month before, in May 1934, modernist poet Osip Mandelstam had been detained by the Soviet secret police. He had recently recited to friends, including Pasternak, a poem crudely satirising Stalin. Pasternak admired Mandelstam but rejected this piece of political invective as not only extremely dangerous for its author and those who heard it but also unproductive in this early stage of building socialism.

“We’re different, Comrade Stalin,” a surprised and intimidated Pasternak responded. Was he afraid of the consequences of admitting to his friendship with Mandelstam? Did he simply not want to judge a fellow poet so different in style? Or were there other factors at work? Whatever it was, Stalin didn’t consider Pasternak’s reply to be satisfactory.

“Is that all?,” he barked. “So much for your loyalty to a friend.” Then he hung up. Pasternak tried to call back to explain himself, but the line was dead.

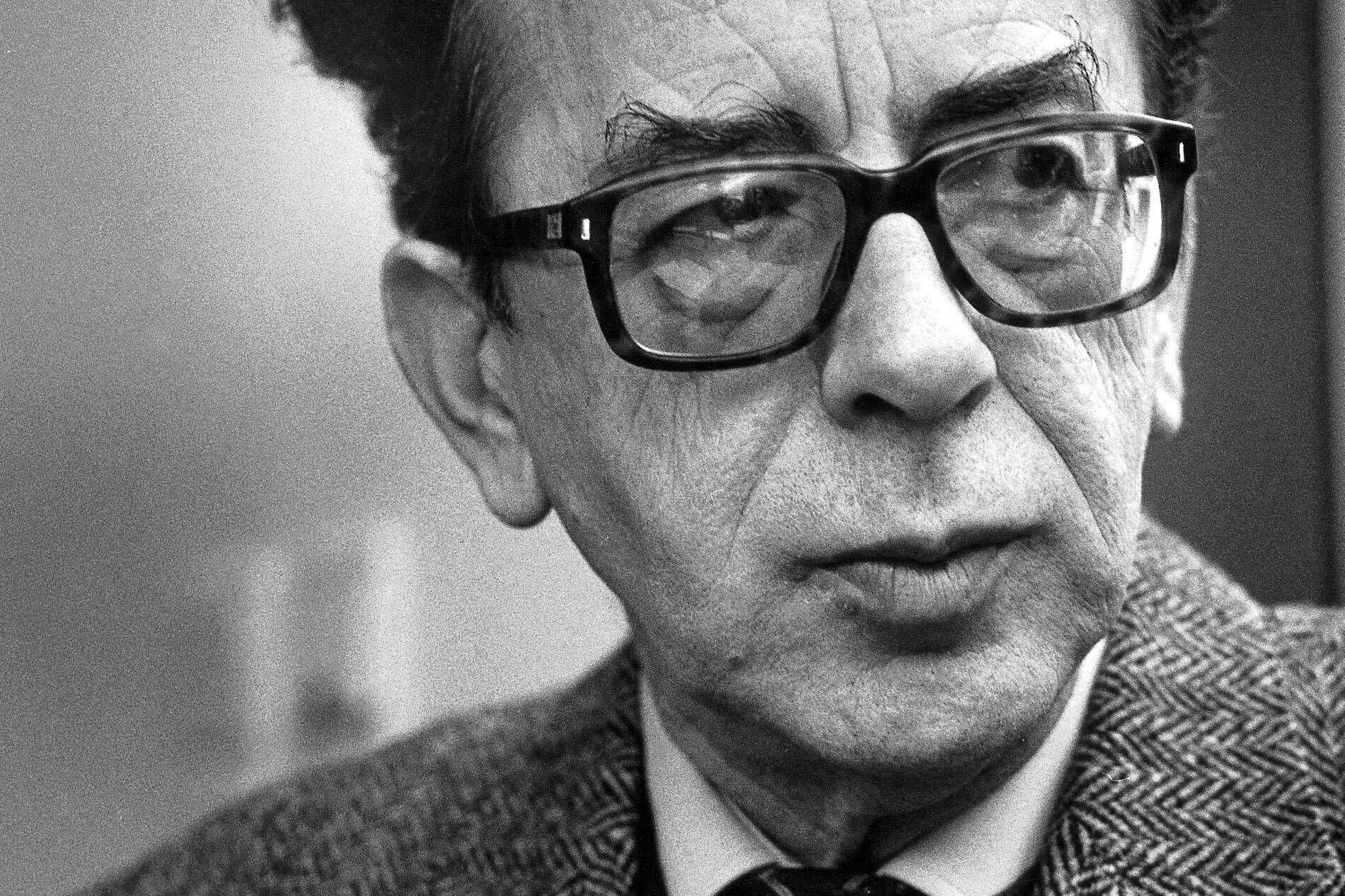

This three-minute phone call is the subject of A Dictator Calls, the last novel by the leading Albanian writer, intellectual and multiple nominee for the Nobel Prize for Literature, Ismail Kadare, who died in July last year. In multiple versions of the brief conversation, Kadare expands those three minutes into a riveting study of the relationship between dictator and poet.

Mandelstam had revealed under interrogation, or perhaps torture, the names of friends who knew of the poem. But none of his friends knew whom he had named. Stalin was less intent on condemning Mandelstam at this point than testing Pasternak’s loyalties and checking his network. His call to Pasternak was recorded by the secret police.

Thanks to the hot-house atmosphere of the Moscow literary world, many different retellings of the conversation exist. Pasternak himself mentioned it in his memoirs. Mandelstam’s wife Nadezhda, poet and friend Anna Akhmatova, and the leading socialist realist novelist Ilya Ehrenburg all wrote up differing accounts. The Russian-born British intellectual Isaiah Berlin records the incident in his “Conversations with Russian Writers” of 1956. Recent Russian historians have traced thirteen retellings of the event. For Akhmatova and many others, Pasternak had simply abandoned his friend.

This all happened at a time of upheaval and change, when figures with pre-revolutionary bourgeois origins — including Akhmatova, Pasternak, Mandelstam and Mayakovsky — became pawns in the literary and ideological battles to establish Soviet socialist realism.

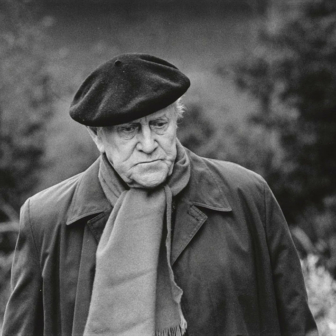

Many years later, in 1958, the ageing Pasternak was himself under attack. His deeply non-socialist novel, Doctor Zhivago, had been refused publication in the Soviet Union and Pasternak had been tried behind closed doors by the official writers’ union. When the novel was published in Italy and then throughout the West, critics reminded him of his earlier abandonment of Mandelstam. The authorities’ hostility deepened when Pasternak was awarded that year’s Nobel Prize for Literature. The young Kadare, a student in Moscow at the time, retained the memory of those events through his writing life.

Despite the generational difference, similarities existed between Kadare’s Albania and Pasternak’s Soviet Union. Albania under dictator Enver Hoxha remained resolutely Stalinist; no post-totalitarian reforms took place after the break with Nikita Khrushchev in 1961. Hoxha rejected Khrushchev’s de-Stalinisation program, repatriated all Albanian students from eastern bloc nations and closed his nation off from the world.

This background is the key to Kadare’s late interest in the momentous phone call that brought writer and dictator onto a collision course. In Kadare’s allegory, Pasternak is the writer per se and Stalin the dictator. But this is not a clichéd tale of oppression of the humanist imagination. Kadare remained obdurately opposed to such readings of dissent in Stalinist Albania.

Kadare’s novel begins with a dream: the narrator is back in the Moscow of his student days, reliving the horrors of the harassment campaign against Pasternak. Doctor Zhivago has appeared in Italy, Pasternak has been awarded the Nobel Prize and is dying in his dacha in Peredelkino, the Communist Party is howling for the writer’s blood. But in the dream it is not Pasternak, but he, Kadare, who is the object of their fury.

Kadare wakes up back at work in the Writers’ Union offices in Tirana, but history is in danger of repeating itself. Only weeks before, the Albanian dictator had called to congratulate him on a poem he had written. What did the dictator really want? How would he have answered? Kadare had already been named as a potential Nobel laureate. What if he were to win?

In A Dictator Calls, Kadare meditates on the deepest questions of his life, career and reputation in his home country. What was he doing writing works of fiction and poetry under the most oppressive of the communist dictatorships? What is the truth of the opposition between writer and dictator? And how had it affected him on a personal level?

“The poet and the tyrant should never have been put together,” he writes:

But an authoritative voice ensured that it happened. Whether they wished it or not, they were together, two manifestations of the same thing: power. Slave of each other in the same circle of Dante. Torturing each other, each the other’s downfall, whether for three minutes or for as many centuries or millennia was of no importance.

That this battle damaged him as a person is a brutal truth he had recognised already in Albanian Spring, his 1990 reflections on the fall of the regime. There the clash was imagined as the battle of two wild beasts, each inflicting different kinds of wounds. Those dealt by the dictator are immediate and terrible; those inflicted by the writer have a delayed effect, but they never heal.

Throughout his life, Kadare focused on the strength and power of the writer and the weakness of the dictator. In turn, Hoxha found in Kadare someone as cunning, as tenacious and even duplicitous as himself. A writer’s wounds may take longer to have an effect, but the word persists and the damage that it causes can be even greater than the executioner’s blade.

Those who know Kadare’s work will recognise that ambiguity lies at the heart of his imagination. Ambiguity cannot be allowed to exist in the dictator’s universe. But in the writer’s, it is the key to resilience and survival.

Part two of A Dictator Calls takes us decades away from Stalin and Pasternak. It is 2015 and the writer still can’t rid himself of the fascination with that fateful conversation. Kadare revisits Stalin’s call in what becomes a summation of a life’s opposition to tyranny.

Writer and dictator both have weaknesses as well as strengths, and both are dependent on each other in the bizarre dynamic in which words channel power. Each of Kadare’s versions of the phone call throws up new facts, new questions, new interpretations, new interventions by actors and phantasms. A Dictator Calls demonstrates the impossibility — and the undesirability — of single, unitary meaning.

In the thirteenth version, which makes up the epilogue to this fascinating exercise in memoir and fiction, the forgotten central figure, Mandelstam, is remembered. Dictators like Hoxha will die and be forgotten; Mandelstam “and those like him” are never “finished.” They die, even at the hands of the dictator, but they are not forgotten. They are “without end.”

Born in the southern provincial town of Gjirokaster in 1936, the young Kadare was sent to study literature and writing at the famous Gorky Institute in Moscow. There, he was to be trained as an “engineer of the (Albanian) soul” in the practice of socialist realism. The ferment of the thirties was over and socialist realism was enshrined as the sole mode of Soviet literature and art.

Doctor Zhivago had been circulated in handwritten samizdat form within the Soviet Union, the form in which Kadare came to read it. When it arrived at the height of the cold war, Pasternak’s Nobel Prize was seen as a major literary-diplomatic provocation by the Soviet authorities. By this time old and infirm in his late sixties, Pasternak was hounded into an early grave.

In his classes at the Gorky Institute, Kadare learned the fundamentals of socialist realism. As a viewer of Pasternak’s humiliation, however, he learned deeper truths about the role and fate of the writer under communism. He recounts the story of this time in Moscow in one of his most accessible autobiographical novels, The Twilight of the Gods of the Steppe and his reflections on the education of the communist writer reappear in A Dictator Calls.

Kadare returned to his native land in 1960. He found himself back in Tirana both as a journalist and writer — a privileged member of the Albanian intelligentsia — and a writer of ironic and subversive works in an environment where dissent was dangerous. He missed the cosmopolitanism of the Soviet capital.

He had little choice: he knew that he could not survive as an Albanian writer outside his native land. But the experience of the Pasternak affair was decisive and he was resolved to resist. He had begun as a precocious adolescent in a communist Albania that was full of hope after a devastating war. After returning from Moscow he evolved into a bitter critic.

Unbeknown to him, he had a wildcard in the form of the dictator himself. Hoxha was a ruthless operator, but he wanted recognition in his own right, outside Albania and especially in France, as a writer and intellectual. Especially in the early days of his regime, when communism was bringing about improvements in a war-torn and backward land, he saw in Kadare a means of proving himself to the world.

Hoxha wrote his own political and theoretical works, adding up to many volumes, and employing bilingual aristocrat and political prisoner Jusuf Vrioni to translate them into French. For his own reasons, he also sided with the younger generation of writers.

When Vrioni discovered Kadare’s writing and began spending his own time making translations, a lifeline was created for the novelist. The General of the Dead Army was published to international acclaim in Paris in 1970. Now known in the West, Kadare could not simply be dispensed with by a disappointed dictator.

For a decade the relationship between Kadare and Hoxha was a sophisticated game of cat-and-mouse, the dictator emulating Kadare, the writer leading the dictator on, each thinking he had the other under control. Kadare survived thanks to cunning and resilience… and that unspoken competition for the voice of Albania.

Kadare would remain an Albanian writer in his communist homeland, marking a different time to that of the regime. Many of his works have an allegorical setting — the arrival of the Ottomans in the late fourteenth century, for example, in the Three Arched Bridge, or Istanbul in the 1870s in The Palace of Dreams, which describes in its opening pages the central square of Tirana. But the point of reference is always contemporary Albania. Again and again he pushed the boundaries of what could be written. His masterpiece of 1982, The Palace of Dreams, stands alongside Kafka’s The Trial and Orwell’s 1984 as a twentieth-century century masterpiece of political terror.

But the dictator’s protection was growing thinner as the seventies wore on. He was subjected to a trial — this one in public — of the kind Pasternak had faced in Moscow almost thirty years before. By the early eighties it looked as though he might pay for his independent thinking with his life.

Kadare’s output was prodigious and he continued until the end to write fiction and to comment, often bitterly and controversially, on his nation’s post-communist present. Released from the dictatorship’s control after 1990, he spoke his mind fearlessly and often harshly.

In contemporary Western realist fiction, the dividing line between fact and imagination often seems very clear. In Kadare’s world reality is never what it seems; phantasms appear alongside figures from real life.

His works take us to the point where power and language intersect. Their theme is the impossibility of self-knowledge in an environment in which words and meaning are contaminated, even defiled and corrupted. Kafka is Kadare’s forerunner, the voice of Central European existential doubt. Throughout his oeuvre, both under and after communism, Kadare’s novels charted the ongoing deformations of lives shaped by dictatorship. Their sinister and bizarre plots are outpaced by reality alone.

Kadare’s works make clear how oppression disfigures and damages everyone, victims and tyrants, alike. In his novel from the late communist period, The Shadow (1984), smuggled in manuscript form to Paris, he gives anguished expression to the sense of sacrifice demanded of the writer living under a dictatorial regime.

Kadare’s post-communist oeuvre represents a powerful literary coming-to-terms with the past in a country that has struggled desperately to overcome the economic and social deprivations of the communist years. In Spiritus (1996) ghosts from the communist period revisit their lives after the fall of the regime; in The Life, Game and Death of Lul Mazrek (2003), a disfigured corpse is wheeled around the towns of southern Albania to dissuade would-be escapees from trying to swim across the narrow Strait of Corfu; The Accident (2008) tells the story of an obsessive love affair that replicates in the post-communist context the dependencies, humiliations and tenebrous dishonesties of relations under the defunct dictatorship. The old certainties of dogma and oppression are gone but no guidelines have emerged for the present or the future.

Kadare shows how these victims of a despised totalitarianism are unable to escape its deformations even in their most intimate moments years after the fall of the regime. More than ever before, the political is the personal. A Dictator Calls was his final reflection on the battle between tyranny and freedom, political power and literature, reality and the imagination.

There were other sides to Kadare’s work. In novels such as City of Stone (about the Gjirokaster of his childhood and the war years), The Twilight of the Eastern Gods (retelling his time in Moscow) and The Doll (his late evocation of his mother) he looks back over his own life and formative influences, revealing the dynamics of personal and national history. His allegories of Ottoman occupation of the Balkans, The Three-Arched Bridge, The Palace of Dreams and The Niche of Shame, describe the effects of Ottoman imperialism on pre-Islamic, medieval Christian Albania, a country perched until the 1390s between the Eastern and Western churches and with its own folk religions and beliefs. In The General of the Dead Army and The File on H. he allows postwar East and West to confront and engage with each other to tragic and comic effect. In a country where subjective authenticity was a bourgeois falsification, Kadare trod the fine line between the regime’s truth and his own.

By the end of the twentieth century it looked as though dictatorship had had its day. After the fall of the Berlin Wall the literature of Eastern European socialism dropped from view as the world scrabbled for capitalist prosperity. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Vaclav Havel, Milan Kundera and a host of less-known writers disappeared from booksellers’ shelves. Few managed to survive beyond the nineties; some, such as Kundera, tried with limited success to refashion themselves.

But dictatorships are making a comeback, albeit in different guises. Now is the time to rediscover Kadare and the other great dissident writers of European socialism.

In the past Kadare’s novels suffered in the transition to English because of a lack of Albanian translators. Most were translations from Jusuf Vrioni’s French translations rather than the Albanian originals. Thankfully British translator John Hodgson has devoted himself to translating Kadare’s oeuvre from its original Albanian. A Dictator Calls adds to his magnificent record of crisp and accurate English renditions.

Enver Hoxha died in early 1985 at the age of seventy-six. His nemesis, Ismail Kadare, died at eighty-eight, more than thirty years after the fall of the regime. He was the last great witness of twentieth-century totalitarian dictatorship and existential terror. His passing marks the end of an era. No modern writer has better chronicled the complexities of human psychology and political oppression. •

A Dictator Calls

By Ismail Kadare | Vintage | $22.99 | 224 pages