Once upon a time the novel was — well, novel. Some locate its beginnings in English in picaresque fictions such as George Gascoigne’s The Adventures of Master F.J. (1573), or with Aphra Behn’s Oroonoko; or The Royal Slave: A True History (1688). Still others see Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) as the first indisputably great novel in English.

Defoe’s masterpiece remains a classic, its eponymous narrator a totem of inventive endurance. Its opening line — “I was born in the year 1632, in the city of York, of a good family, though not of that country, my father being a foreigner of Bremen, who settled first at Hull” — introduced to an increasingly literate public a narrator anchored in contemporary reality, a blunt, resilient everyman. With Crusoe, the novel in English had arrived. Three centuries on, he speaks to us still.

As so often in the early modern period, though, the Spanish got there ahead of the English. Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote (1605) appeared more than a century before Crusoe, when Shakespeare was still fashioning King Lear. Cervantes gave the world a character to stand with Shakespeare’s greatest figures. Although Don Quixote the character was a throwback to a romantic age already gone, Don Quixote the novel placed him in a realistic world where windmills were windmills.

More generally, the new literary form was concerned less with the deeds of monarchs and dynasties than with adventures and misadventures of the emerging bourgeoisie. Where Shakespeare’s Richard II wants to sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings, novelists such as Samuel Richardson (Clarissa, 1748) and Henry Fielding (Tom Jones, 1749) vividly represented and sometimes vigorously criticised changing moral norms and increasing social mobility.

The novel was also flexible enough to depict tragic figures and grand circumstances. Great Russian novels of the nineteenth century like Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) and Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869) presented social, historical and psychological portraits of profound depth and sweep. English novelists like Jane Austen, Charles Dickens and George Eliot portrayed the social and cultural life of nineteenth century English life with such acuity and artfulness that most of us still understand that world primarily through their depictions of it. The realist novel that flourished in that century gave readers extended and vivid access to their own world and to other people, places and times.

Then, Edwin Frank argues in Stranger Than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel, things changed. Not in the twentieth century, but in 1864, when the Civil War raged in the United States and British and Irish convicts were still being transported to Australia. In that year, Frank declares, Fyodor Dostoevsky was “writing the first twentieth-century novel,” Notes From Underground. Frank considers this “an unclassifiable work — neither novel or novella, at once confession and caricature.”

This intentionally provocative choice is in line with the sort of dislocating manoeuvres Frank sees as central to some of the twentieth-century’s great novels. Where earlier novels presented reality in illuminating detail and length, the novels of the twentieth century questioned reality itself, as well as the characters who inhabited that reality, and indeed the novel’s capacity to portray reality. “In Notes from Underground,” Frank asserts,

the writing explodes and implodes and all the time the writer is trapped inside it, not only unable to get out, but unable to see what he has gotten himself into, an inside that is all inside out, just as his squalid living space, his hole, the hole he is in, is indistinguishable from the space of itself.

Dostoevsky’s unclassifiable work, Frank argues, announces “the voice of the twentieth century novel.” It is a voice that is “supremely equivocal and not just unreliable, radically unreliable. But real.” You need not agree with this take on the twentieth-century novel in general, but it makes you think about what might be an alternative.

The same is true of the specific novels and novelists Frank considers. Is Ulysses, as he claims, really a “book born of the [First World] war”? Is D.H. Lawrence “nothing if not working class”? I would disagree with both these propositions. Frank makes scores of bold and contestable assertions throughout. His study is a sort of cerebral bootcamp, fast-paced and mentally strenuous, but ultimately rewarding. You feel intellectually fitter for having read it, even if, perhaps especially if, you disagree.

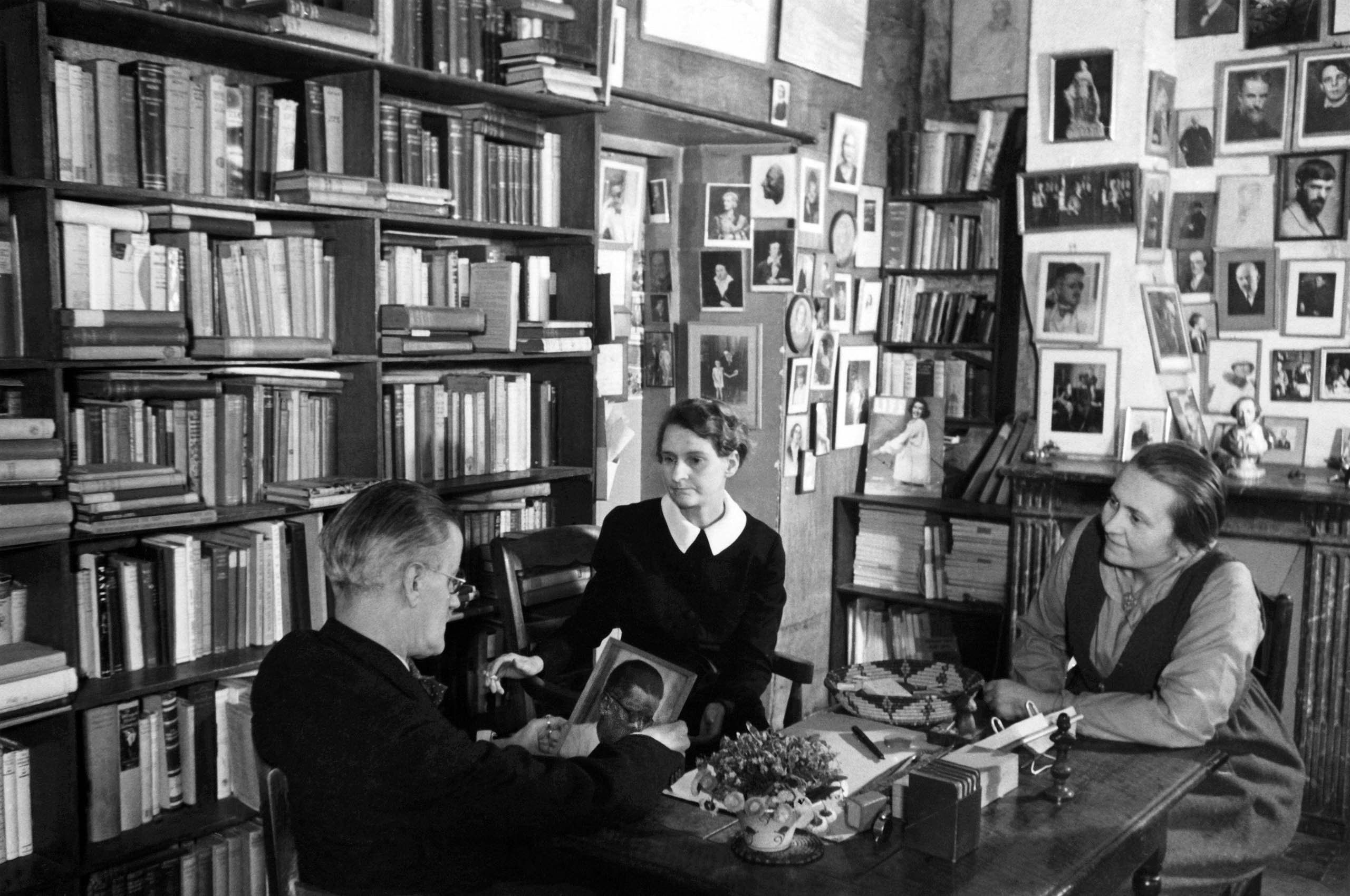

Potential sign-ups for this workout might be encouraged that Stranger Than Fiction is not an academic study. While it does have “Notes” and an impressive bibliography, it is largely jargon-free (the term “modernism” is noted and quickly set aside). Frank reads for a profession, working as editorial director of New York Review Books, the publishing division of the New York Review of Books. This has made him formidably well-read but not clotted his opinions. He writes with insight and flair, commenting for example that Jean Rhys’s works are “unassimilable to feminism” or other twentieth-century -isms, “(apart from alcoholism, perhaps),” and that “without Hemingway, no Bogart.”

His own book, as he notes in the acknowledgements, was fifteen years in the making, the result of wide and deep reading of novels from many parts of the globe, though most of the examples originally appeared in English. He confesses that while looking at more than thirty authors at length he necessarily leaves a great many out, namechecking Rabindranath Tagore, Willa Cather, Mikhail Sholokhov, John Dos Passos, Marguerite Duras, Joseph Conrad and a dozen others. For all the panoramic sweep of this study, there are gaps.

Frank’s method is refreshingly simple. He gives biographical sketches of his chosen writers, linking their lives and circumstances to the works they create, declaring that “by tracking a novel’s turns of events and turns of phrase, its varied voices and points of view one begins to discern how it goes about making sense and how it might matter and continue to matter.”

But this reference of “novel” in the singular undersells what he goes on to do, sometimes considering two or writers in the same chapter and more than one work by a specific writer. This occasionally leads to a certain unevenness, so that Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time (a short story collection, as Frank admits) gets most of a chapter to itself, while James Joyce’s Ulysses and Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time share their allotted space. Admittedly, that chapter is twice the length of the Hemingway piece — but, still.

Chapters are set within a framework that organises what is largely an historically sequential argument into three major parts: “Breaking the Vessel,” “A Scattering of Sparks,” and “The Withdrawal.” In the first of these, perhaps surprisingly, Franks takes H.G. Wells as the writer who represents the view that “the new century demands a new vision of humanity and a new novel to go with it.” Where you might assume that The Time Machine would be that novel, Franks concentrates on Wells’s far less successful if unnerving novel The Island of Dr Moreau, a tough read that deals with vivisection and the splicing of humans and animals. It presents, Frank rightly notes, a world more generally of “terrifying excitement,” the shape of monsters to come.

The rest of this first section covers an impressive amount of territory, from André Gide to Alfred Kubin; Franz Kafka, Colette and Kipling; Gertrude Stein, Machado de Assis and Natsume Sōseki; and three heavy-hitters: Thomas Mann, Proust and Joyce. It is full of sharp questions raised by the books themselves, such as “Are you the kind of reader who recognises just how hackneyed, how uninteresting that kind of authorial bid for the reader’s attention is?” And it shimmers with observations by Frank himself — that the major works of Joyce, Proust and Mann (The Magic Mountain) “are not war books, yet they might be described… as having been written by war.” As ever, there is room for dissent.

The second section, “A Scattering of Sparks,” deals with the interwar years, which for Franks is when the twentieth century proper comes into being. His subjects include Virginia Woolf and Robert Musil, Hemingway, Italo Svevo and Jean Rhys. These writers test out the new possibilities opened by the Joyces and Steins and Prousts, while creating new ways of seeing and depicting the troubling world emerging.

In Mrs Dalloway, for example, Frank sees Woolf exploring without the use of an identifiable narrator “how it feels, moment by moment, but also year after year, to be alive,” how past and present, the inner and outer worlds of a range of characters intersect or remain discrete, are acknowledged or ignored. Accepting Eliot’s view that Ulysses had no single style, Woolf made sure that her “style, her voice, her vision is everywhere unmistakable in Mrs Dalloway.” Her book manifested in literary terms her dislike of Ulysses.

Questions of style are also critical in Hemingway’s In Our Time. Drawing lessons from Stein, Hemingway avoids “plot and character, those building blocks of the nineteenth-century novel” to write, as his alter ego Nick Adams wants to write, “like Cezanne painted.” The exploration of how, or indeed if, the novel can represent the grave new interwar world and its inhabitants finds insistent form in Musil’s monstrous, incomplete The Man Without Qualities, which for Frank is “an exercise and an ongoing emergency, the question of what kind of book that it is and if it will ever end being more central to the book that it is.” We are close to Dostoevsky and a long way from the world of Jane Austen.

The same can be said about the short 1920s and 1930s novels of Jean Rhys. These deal with financially vulnerable women living off their wits and fading looks in a cruelly unsentimental metropolitan Europe. As Frank appreciates, these brilliant works are “very much not the vision that Mrs Dalloway presents at the end of Woolf’s novel — ‘for there she was’ — of a woman realised.”

With their joyless sex, often a form of financial bartering, Rhys’s novels are also not the vision of the subsequent novelist Frank deals with, D.H. Lawrence. The Rainbow and Sons and Lovers, Frank argues, exemplify Lawrence’s view that “sex is the lived centre of human experience, a supremely ambiguous power that both defines and defies everything we are,” something “comparable to a certain mystical picture of God.” We are a long way from the world of Virginia Woolf.

Part III, “The Withdrawal,” looks at how novelists after the First World War continue to experiment with form and voice and perspective. They also try “to reckon with the scandal of the century’s history” in its global complexity and uncertainty. Some of Frank’s choices, such as Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, are unsurprising, although, as with his interpretation of earlier novels, he has plenty of interesting things to say about them. Other choices are slightly left-field, including Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, the latter creating a scandal rather than reckoning with history. That book does allow him to quip that none of Nabokov’s precursors “wrote sentences or composed novels of such consciously licked finish.”

What Nabokov does do is to write about the exile so prevalent in twentieth century literature, a figure captured in V.S. Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival. Frank sees this semi-autobiographical novel as circling around itself, “a book about how the author came to write just this novel.” But in addition to being about the processes of writing and being a writer, it is also about the historical collapse of empire and of displacement. In England, the unnamed narrator (like Naipaul, of Indian descent and Trinidadian upbringing) is “a lonely man, living in a place where he is not at home, and with no home to go back to.” How far are we from the world of Daniel Defoe?

In David Lodge’s 1975 campus novel Changing Places the members of the English department play a game called Humiliation in which they are required to admit honestly to not having read a classic they assume all their colleagues have read. They get a point from each person who has read that classic. The winner is the one willing to admit to not having read a classic every other player has read. Hence the name of the game, which plays on the general fear lecturers have of being exposed as less than omniscient.

One lecturer who misunderstands the underlying principle of Humiliation puts forward extremely obscure classics that he has not read to signal his otherwise encyclopaedic reading. But because no one else has read these works, he gets no points from his colleagues. He then susses out what he needs to do to win the game and admits to never having read the text of Hamlet, only ever seeing Olivier’s film version of it. This wins him points from all his colleagues. Subsequently, though, he misses out on tenure, the suspicion being that his university could not give a permanent position to someone who had publicly admitted to not having read Hamlet.

We might guess that Frank’s omnivorous reading would mean he would not do well at Humiliation. He has read both wisely and well. In addition to the books he considers and those he admits he would have loved to include, Frank also provides an appendix titled “Other Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel.” Another fifty writers are listed, each with a representative work or two. Again, provocatively, the list begins even before Notes from Underground, with Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights (1847). The only Australian entry is Shirley Hazzard’s The Transit of Venus (1980). Frank describes this list as “an acknowledgement of omissions.” Perhaps there will be a follow-up.

As it stands, Stranger Than Fiction offers readers interpretations of individual novels and a way of stepping back and considering the process of reading itself. It asks us to consider not only what we read, but why we read, and how we read, the patterns and themes, tendencies and techniques we discern that necessarily require thinking beyond individual novels or novelists. As he admits in the introduction, “the selection is personal,” adding that “I have written about books that move me.” His book encourages us to come up with a different argument, one that speaks to the uniqueness of our own reading experiences. Indeed, the examples noted in “Other Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel” suggest that Frank himself might have come up with a substantially different book had he followed this list.

The book is energised and enhanced by this personal approach, but it is not without its dangers. Although it is broken up into three largely chronological sections, the overarching connections are not overly strong. One effect of this is that the book’s timeline is sometimes wonky. So, for example, Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers (1913) and The Rainbow (1915) are dealt with in the interwar section next to Rhys’s novels of the twenties and thirties. Lawrence’s works belong chronologically in the opening section, and in fact were published well before the masterpieces of Joyce and Proust considered in Part I.

We might think that Frank organises his chapters this way to contrast Lawrence’s treatment of sex with that of Jean Rhys. But while the examination of Lawrence immediately follows that of Rhys, Franks develops no connection. This absence of connective tissue happens more than once, so that while the book is packed with informed comments and brilliant expositions, the larger argument is harder to discern. Sometimes it feels that this study is a brilliant set of short stories rather than a coherent narrative. Which may be the point.

Stranger Than Fiction will activate a lively and possibly confrontational discussion with each of its readers. Offering us a peculiarly informed person’s personal history of twentieth-century novels, it simultaneously encourages and requires us to come up with a better argument. Or at least a different one. It is less an academic lecture than a lively and extended conversation with an eloquent and highly intelligent reader. I finished it with a list of writers and works I feel compelled to read. I won’t tell you which ones. That would be humiliating. •

Stranger Than Fiction: Lives of the Twentieth-Century Novel

By Edwin Frank | Vintage | $36.99 | 480 pages