“There are three rooms here in the Gran Café de Paris, each reserved for specific clientele,” declared Hashim, my bookish, puckish guide to Tangier and its literary past. “Where we are: this is the general place for men to meet.” “Over there,” he said, pointing his sugar sachet behind him. “That is for gay men. It is no problem to be gay here.” “And the other?” I asked. “Men seeking prostitutes,” he declared. “This cafe is just like it was in the time of Bowles and his circle.”

The writer Paul Bowles was among the reasons I wanted to visit this city on the northern tip of Morocco. Writers flocked to Tangier following the Second World War, when it was capital of the evocatively named International Zone. Bowles was at the centre of an eclectic literary cast that included William S. Burroughs, Truman Capote, Jack Kerouac, Patricia Highsmith, Allen Ginsberg and Gore Vidal. Each mined the scenes around them in their works.

There was certainly plenty of material. The Tangier of those days was an anything-goes place ruled loosely by European powers and populated with a cast of barons, bounders, boulevardiers, black sheep, desperadoes, exoticists, spies, sensualists and assorted flotsam and jetsam. After reading so much of their writing in anticipation of the trip, these literary ghosts seemed so alive to me in this mahogany old cafe that some of them could have been sipping mint tea at nearby tables. Hisham said he was delighted to show me some of their haunts, a deviation from his staple work of taking roly-poly tourists from cruise ships on food tours. At least that was the story he told me.

I first came to know of Bowles when I was told he’d named the ill-omened male character of The Sheltering Sky, his first and most remembered novel, after a city I knew all too well. The man’s name, somewhat preposterously, was Port Moresby, a nod to a city Bowles had never visited but intuited as being an epitome for existential desolation. Moresby, his wife Kit and their acquaintance Tunner make up the tangled and doomed triangle at the book’s centre. Side characters include a callow young Australian, Eric, and a ghastly woman introduced as his travel writer mother, it being entirely ambiguous to the reader throughout as to what their relationship is.

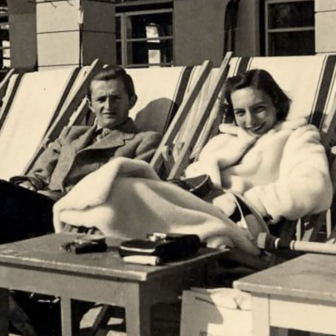

Many elements of The Sheltering Sky were autobiographical. Kit had many of the characteristics of Bowles’s wife Jane; Eric and his mother were thinly fictionalised versions of figures Bowles wrote after encounters on his travels. There was a gossamer thinness between his fiction and nonfiction, phrases and scenes from one form popping up in the other.

I’d finished rereading this strange, sad, haunting novel in a bar in Tarifa, the Spanish port town from where the ferries depart for Tangier. Perhaps it was the immediacy of the words, but the bar itself seemed populated by characters with similar attributes, the most obvious of which was a middle-aged American woman in multicolour kaftan feeding cheese to her dog while monologuing tales from her miserable childhood to a bored young man who looked sure to be her unhappy lover.

Nothing good awaits any of the characters in The Sheltering Sky as they fan across the Sahara. One dies, another is willingly imprisoned as a concubine; throughout, characters cogitate about their inconsequential place in the universe, “how fragile we are” under the sheltering sky of the title.

But the novel is positively upbeat compared to some of Bowles’s short stories. A fiction-writing friend of mine had urged me to read “A Distant Episode” as part of pre-trip reading but warned I would find it hard going. I did. The story is about a trusting linguistics professor who returns to the site of his fieldwork somewhere in the Moroccan hinterland. Expecting acclaim, the hapless don instead finds himself tortured by relatives of his former informants who mock him for not understanding their dialect. Tennessee Williams — another member of the city’s rotating cast — told Bowles to spike another of his short stories lest readers think him an outright monster.

Bowles’s writings are certainly much easier to admire than adore. Yet I have always been drawn to them and his ruminations about travel, place and our place in the world; I’ve probably read him as deeply as any writer. Many of his stories serve as cautionary tales, speaking to a fear that travel doesn’t so much enable discovery so much as to reveal personal flaws and insecurities. No matter how much outsiders strive to understand another place, they will remain largely deaf and dumb to both the place itself and, in many ways, their own motivations. As someone who has lived a lot of his life overseas and tried to understand places far from my own, Bowles’s observations pointed to a melancholy conclusion that was uncomfortable yet necessary to ruminate on.

I was also in Tangier as a halfway stop to Australia after years in the United States, reckoning with a return I was at best ambivalent about. We were in Morocco the week before a new president would be inaugurated in Washington and the world seemed frozen in purgatorial uncertainty about what would come next. To put it another way, I was in a profoundly Bowlesian mood, a disposition enhanced still further by the presence in my backpack of a dogeared and often read copy of Travels, his collection of non-fiction pieces.

I asked Hisham if people still come to Tangier seeking to make it as writers. “Not really,” he replied. “Everyone wants to be a YouTuber and a Tiktoker nowadays.” My own children aspire in similar directions; their dreams seem faintly ludicrous but no sillier than my own dream from adolescence of trying to make it as a writer.

And maybe they are onto something. There were probably a hundred people in the Gran Café de Paris. One person was reading a newspaper, another a magazine, a few chatting among themselves and the remainder watching their phones impassively. Just hanging on in the city are bookstores dating from Bowles’s time, including the Librairie des Colonnes, a place he seldom visited because he said he feared the djinn (ghosts) that haunted it. It was Sunday when we went on our walking tour and the bookshop was closed, but I peered in the window and noticed relatively few volumes on the stands. I started to feel ever more like I’d chosen the wrong dream to chase.

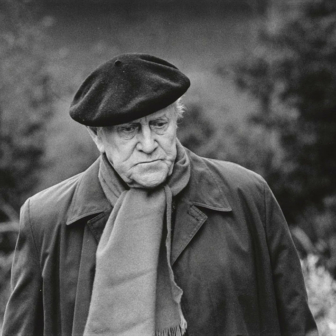

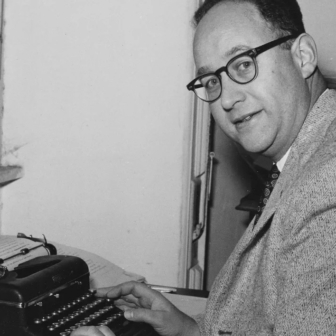

Hisham had a couple of stops planned out for us, the first being Bowles’s old apartment well outside the gates that marked the International Zone. Bowles spent sixty years in Tangier and forty of them, up to his death in 1999, in that apartment. Photos I’d seen the day before in a small exhibit at the American legation in Tangier — the building that housed the United States’s first overseas mission — hinted at Bowles’s affectations and peccadillos as well as revealing brutally the ravages of time.

In the first photo he is a young blonde dandy in a Liberace style dressing-gown complete with unfeasibly long cigarette holder, a man consciously aware he is at a literary height. In the next he is typing purposefully on his typewriter. Another photo shows the apogee of the lurid Orientalist fantasia that by many accounts the libertine Bowles indulged lustily: a now grey-haired man, imperious in a three-piece suit, flanked by a phalanx of robed striplings, extras in the production of Salome whose music he scored.

But the most affecting photos are from Bowles’s final days, sitting up in the bed where he did all his writing. He is emaciated, jacket pulled tightly over shrunken shoulders. He was already close to becoming a ghost writer.

On our way, we passed by an unremarkable shoe shop, above which Hisham said the singer James Brown once played. We talked about whether Tangier’s lurid mystique constituted a blessing or a curse. I was travelling with my family, and an Anthony Bourdain documentary about the city I’d watched with my eldest son had perturbed him no end. Bourdain depicted Tangier as depraved, dark, dangerous and drug-addled (for Bourdain these were all attractive attributes of course). We had girded ourselves to hurtle straight into a dystopia, a concern exacerbated by listening in to the conversations of supposed experts giving unsolicited advice to jejune newbies like us in the passport queue about how every Moroccan was primed to gouge the unwary traveller.

The reality was anything but. Expecting braying hordes of touts and peddlers, we instead met a polite man in a brown desert robe (evoking an Obi-Wan presence) who directed us into an airconditioned taxi that charged a price ten times less the figure the doomsayers in the queue had warned us about.

We’d been walking for twenty minutes now when we reached what we thought was the approximate location of Bowles’s apartment. While Hisham had taken a group here before, he couldn’t quite remember in which of the samey yellowish housing complexes it was located. Asking around didn’t help much either. Even though he probably would have served him in the decades prior, the elderly grocer had never heard of Bowles. Nor had the young man in the Paris St Germain shirt watching a football match on his phone.

Eventually a stooped woman directed us to a gloomy entranceway. A stone plaque with Arabic and English lettering at the foot of the stairs read: “Paul Bowles, American Writer & Composer lived here.” A family bustled up the stairs with their shopping and another came down the stairs as we took a bunch of pictures. A quote from another writer I admire, W.G. Sebald, came to mind: “to set one’s name to a work gives no one a right to be remembered, for who knows how many of the best of men have gone without a trace.” The apartment is supposedly occupied now by his last houseboy, who would now himself be an old man. We lingered for a time, too embarrassed to knock on the door.

On the way back to the old city and our next destination, we passed by the sprawling palm-fronded Spanish consulate, a place where acquiring a visa, Hisham told us, could take up to three months for Moroccan citizens like him. “The process gets harder and harder,” he lamented. Many of those who did make it over found the cost of living in Spain overwhelming but were too ashamed to admit it and return. Hisham shelved their reports of glittering lives in Europe in the part of his brain marked “fiction.”

For all that, getting to Europe remained the dream of many, including Tangier’s newest residents, who stand out today as much as the dandy writers did of old. These are the sub-Saharan Africans, many of them selling laughably phoney wares, such as T-shirts I saw bearing the combined logos of North Face, Versace and Nike.

Many of these new Tangerines see the city as a way-station to elsewhere, a stopoff to acquire a smuggled passage to a Spanish beach in dead of night. “Who takes them,” I asked. People connected with the drivers of the ostentatious Mercedes and BMWs cruising Tangier’s streets, Hisham told me. This closet African city to Europe retains the air of a smugglers’ paradise.

We talked about Bowles’s complicated life and legacy. He fell out with, and was eventually disowned by, many of the Moroccan writers whose work he translated. The causes were familiar to anyone who has been involved in a joint writing project: disagreements about the pulling of weight, attendant spats involving credit, status and bruised pride.

Other stuff was darker. The writer Michelle Green writes about how Bowles devised a scheme as dark and sinister as any of his fictions that preyed on the insecurities of an upstart American writer and drove the man further into madness. The Guardian obituarist wrote a dark tales reminiscent of a Bowles story about how he’d repressed a memory of waking wearing a djellaba robe one morning in the writer’s apartment after an evening of enthusiastic hashish piping, his clothes strewn at the foot of the bed.

There was much poignancy too. Jane spent much of their marriage rotating between psychiatric institutions, flamboyant and costly affairs and Tangier barstools where she would run up huge bills and lament how unfulfilled had been her literary career. When Paul Theroux visited Bowles at his home near the end of his life, he found the old writer shivering in a thin blanket, largely forgotten by a literary world that once renowned him. The man who wrote cautionary tales had become one himself.

We passed the el-Minzah, still one of Tangier’s most storied hotels and a hangout for Bowles on the infrequent occasions when he had money. Another peril of being acclaimed as a “writers’ writer” is the rare and small royalties. A better remunerated writer, Ian Fleming, spent a month a year there writing James Bond novels. We peeked inside its stately courtyard, its walls festooned with pictures of visitors from yesteryear: European royalty, movie stars from my grandparents’ era; John Malkovich, who played Port Moresby in the film version of The Sheltering Sky; and somewhat incongruously the former Australian soap star Melissa George.

Several stars downscale from the el-Minzah is the whitewashed El Muniria hotel, nestled inside a warren of streets in the old city. The El Muniria is a basic, no frills, no ensuite type of place. There are much better hotels in Tangier but none had as many literary ghosts for guests to séance with.

Old sepia photographs of Ginsberg, Kerouac and Bowles hung here and there but the more prominent person staring from the walls was a sinister-looking fellow with dark glasses and a porkpie hat. He was William S. Burroughs, a man who made even the most outré residents of the International Zone seem placid by comparison. He had arrived in Tangier after killing his wife in a William Tell–style escapade in South America; his life in Tangier was only marginally more sedate. His hotel room was pocked with bullet holes, a stove burned inside for his hashish candy and the floor was carpeted with discarded pages of a novel Jack Kerouac would ultimately pick up and organise into Burrough’s most celebrated work, Naked Lunch, a fever dream of a book revolving around an opioid-addicted man who lives in a city called Interzone.

While I found Bowles’s writing can’t-look-away absorbing, I struggled through Naked Lunch, flailing because of its absence of obvious structure. Burroughs had written the book in such a way that it could supposedly be picked up at any page and read from there. I found it easier to put it down.

The hotel was excellent for people watching. I typed into my phone some of the novelistic characters we saw as we puttered around. A man with an English accent, Tudor yeoman face and Arab robes speaking loudly on his phone; two blonde men with identical leather jackets and handlebar moustaches speaking German and holding hands. On the roof, a young man was speaking to a phone perched on a tripod; scrolling around the internet a few weeks later, I found him enthusing in a brash video with crazed graphics that the hotel rooftop is one of the “must do sites” in Tangier. My initial thought was to scoff until I realised that if they were around now, those literary swaggerers and experimenters with form might well have been doing the same.

We headed back to the Gran Café de Paris to meet my family and embark for the afternoon, entirely without irony, on one of Hisham’s food tours, which culminated in the purchasing an assuredly counterfeit soccer shirt in the red and green colours of the Moroccan national team. Very excellent the tour was too.

Readers can get a sense of what a place is like only if they know its effects upon the writer, Bowles wrote. What had I learned from my few days in Tangier? Obviously, the city was very different from the dark image of my imagination. On its surface, it exuded an easy PG-13 charm and affirmed to me that always the best way to get a true sense of a place is not rely on the others but to go and see.

We called back to the El-Minzah later that afternoon for drinks. Hisham met his next client, an elderly Frenchman who wanted to see one last moon rise in the desert, and my family and I had drinks in the beautiful cool courtyard. My children could not identify a single person on the wall, their legacies faded already. They had lemonade and my wife and I had a Casablanca lager while we tried to tell them about people like Richard Harris and Rex Harrison.

I remember thinking that this was a perfect moment, something I remembered existential Bowles said was one of the things that made life worth living. It was from his novel The Spiders House, set during the anything-goes years the International Zone. I winkled out the full quote later: “the only thing that makes life worth living is the possibility of experiencing now and then a perfect moment. And perhaps even more than that, it’s having the ability to recall such moments in their totality, to contemplate them like jewels.”

While I wasn’t at all sure what the future would be for me, I had a happy family. Perhaps that was as much certainty and surety as one was going to get afforded in this mad world.

My wife and I could happily have stayed for another drink, but the perfect moment was already fading. Why is it that kids just don’t seem to enjoy kicking back in bars as much as their parents? We headed up the stairs once more to hail what would turn out to be another reasonably priced taxi. The door opened into us and the burly Englishman in the Arab robes from the el-Muniria swaggered purposefully in the direction of the bar. We stepped out, once more under the uncertainties of the sheltering sky. •