Government schools, even in Queensland, will at last get the full Gonski. That is a win: not as big a win as it would have been in 2012 when the “I Give a Gonski” movement was riding high, and more a relief than a breakthrough, but an important win nonetheless. It will help government schools do what needs to be done and lift the morale of those who work there.

It is also a win that leaves a void. For a decade or more the “full Gonski” has been the central demand by and for government schools. What now?

Money will have to be a key part of any answer simply because “needs” are now greater than they were when Gonski popularised the “needs-based funding” idea. Just about everyone in government schools deals with steadily rising numbers of kids who don’t want or refuse to go to school, kids who are lonely at school or who have no “engagement” with it or “attachment” to it, kids who bully or are bullied, not to mention significant numbers of kids who once were out of sight and mind in “special schools” but are increasingly integrated into mainstream classrooms.

For these and other reasons many in government schools want a kind of schooling different from that assumed by Gonski. Gonski thought that equality could be served by shrinking the “long tail” of “student attainment” in “the basics.” That has turned out to mean NAPLAN and My School, objects of fear and loathing in government schools. Many are trying to figure out how to get kids to “flourish” or “thrive” or “pursue their passion” or “develop a broad range of capabilities” such as knowing how to learn, how to collaborate, how to contribute to the wider community. Getting from the Gradgrind world of NAPLAN, My School and the vocabulary of “outcomes,” performance” and “teacher quality” to that kind of schooling is slow, hard work, and it costs.

The trouble with campaigns that include money is that the money pushes everything else to the margins and encourages the idea that if only we can get the money all will be well — which of course it isn’t. And campaigns driven by teachers in government schools invite sceptical publics and politicians to believe they are simply feathering their own nests (or, when non-government school funding is invoked, to talk about “the politics of envy”).

So, some suggestions:

• Push for more money, but put parents first. Having even one kid at school imposes costs that many government school parents struggle to meet — “voluntary contributions” (from a few hundred dollars a year to more than $2000 at the high end), uniforms, IT, school camps and excursions, after-school care —and that’s without the kind of sport and cultural development programs taken for granted elsewhere.

• Tackle the creeping social segregation of schooling (poor kids going to schools with other poor kids, rich with rich), now worse in Australia than in just about any other rich OECD nation. Pushing back means pushing for a single set of rules for all schools about choice (by families) and selection (by schools), and steady movement toward common funding, including a funding ceiling to go with Gonski’s floor, and full public funding for non-government schools willing to ditch fees and work toward a broader social mix.

• Revive and emphasise Gonski’s call for all extra funding to go direct to schools and not to central authorities.

• Resist Gradgrind schooling by changing the way NAPLAN is administered and used, including abolishing school-by-school “performance” disclosures on My School.

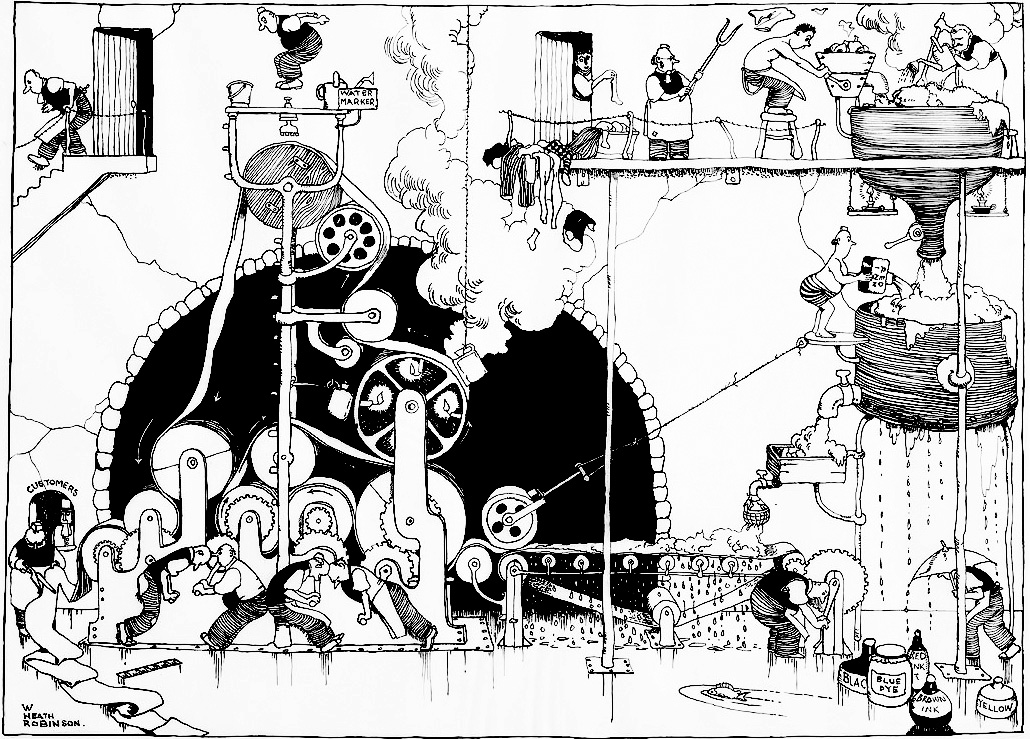

• Perhaps the most important single lesson of the Gonski saga is that by the time the last increment of full funding arrives (2032 apparently) “the system” will have taken just over two decades to get from announcement to the implementation of what is, after all, a relatively modest reform. “The system” — a Heath Robinson contraption of nine governments, three sectors, a group of “national” agencies and instruments and another whole layer of the same kind of thing in each state/territory — couldn’t organise the proverbial chook raffle, yet it presumes to tell schools that they’re the ones that have to be reformed. The reality is almost exactly the other way about. A reformed governance of public schools — a lot fewer cooks, a lot more distance from governments and ministers and election cycles, and a lot more willingness to encourage from below rather than dictate from above — would do more to lift government schools than any number of “national school reform agreements.” •