In 1942, midway through the second world war, the artist Sidney Nolan was conscripted into the Australian army. Posted to the Wimmera in isolated northwest Victoria, he did his bit to protect Australia from the Japanese Imperial Army over the next two years by valiantly guarding storehouses of wheat.

The twenty-five-year-old Nolan was an unlikely soldier. There’s a grainy photograph of him taken just a couple of years earlier, in 1940, that perfectly captures his nonconformist nature. He’s sitting on a pier in St Kilda with his first wife, fellow artist Elizabeth Paterson, squinting suspiciously at the viewer, his unruly hair held back by a thick head band. Decades before the invention of rock and roll, he looks for all the world like guitarist Keith Richards. You have to wonder what staid Melbourne or the Australian army — or Paterson’s parents for that matter — thought of this unrepentant bohemian.

Nolan’s Wimmera interlude must have felt to the young artist like an unjust exile into a pit of irrelevance, but in some ways it was the making of him. Wherever he was stationed — Dimboola, Horsham, Nhill — he would set up a rudimentary studio and get to work. During this khaki sojourn he also had a lifeline to the outside world: his lover Sunday Reed.

Nolan had left Paterson and his young daughter Amelda in 1941 to take up with Reed — and her husband John Reed, to form probably Australia’s most famous ménage à trois. He eventually moved to the Reed’s property Heide, a small farm on Melbourne’s northeastern outskirts, where an informal artists’ colony flourished under their patronage. After the war, Nolan would paint his famous Kelly series on the dining table at Heide, often with Sunday by his side. By the late 1940s, however, the love triangle would fall to pieces. Nolan left and never returned.

But that was all in the future. During the war Nolan and Sunday were very much in love. She would post him sheets of Masonite and muslin-laid boards to paint on, and tins of Dulux lacquer and Ripolin enamel to paint with. Nolan, an autodidact with a love of public libraries, read voraciously, so Sunday also sent him books: Rimbaud, Kafka, Kierkegaard. On leave he would return to Heide; sometimes Sunday would visit him.

She also encouraged Nolan to paint the landscape around him. In the Wimmera, Nolan and his fellow conscripts laboured under a vast dome of blue sky, surrounded by flat fields of yellow wheat interlaced with interminable roads and railway lines. In the distance they could see ancient rocky outcrops worn down from what were once mountains. Nolan captured all this, and more, and developed rapidly as an artist.

And then he did something out of character: he applied to become an official war artist. In the archives of the Australian War Memorial you’ll find the letter of application he wrote to the man in charge of Australia’s war artists, a lieutenant-colonel named John Treloar. Pinned to it is a note that describes Nolan “as an extremist of the modern school.” He didn’t get the gig.

Treloar was a veteran of Gallipoli, where he had almost died of typhoid. Later in the war he worked closely with Charles Bean, the progenitor of the Anzac legend, in the Australian War Records Section, collecting documents and artefacts and commissioning artists for the memorial Bean had decided must be built. After the war, he became the second director of the AWM. The paintings Treloar wanted to adorn the walls of the memorial had to be factual, consoling and inspiring.

But imagine if Treloar had taken a punt on the young artist. Imagine if Nolan had been sent off to New Guinea with a haversack full of Ripolin and a melancholy kiss on the mouth from Sunday Reed. Imagine what Nolan may have taught us about Australia’s war in the Pacific.

In 1944, fearing he might be sent overseas to fight, Nolan went absent without leave. It seems he was willing to paint for Australia; but not to fight for it. On the run, he took up the pseudonym Robin Murray and, with the help of the Reeds, managed to avoid the authorities until 1948, when an amnesty allowed him to become Sidney Nolan again. While he was mythologising Ned Kelly in paint, Nolan himself had been an outlaw.

There is little in Nolan’s work during the war that is overtly about the war. The best-known are Latrine Sitters and Dream of the Latrine Sitter. The titles speak for themselves: they are the paintings of a young man resentful at having to suffer the depredations of army life. Neither painting is in the spirit of Anzac as Colonel Treloar would have understood it.

But one work stands out, mainly because Nolan would later return to the image again and again. Painted in 1942, Head of a Soldier shows a digger in a slouch hat with the staring eyes of a soul in the grip of post-traumatic stress disorder. Not surprisingly, it was used on the cover of a book called Psychiatric Aspects of Modern Warfare.

More than a decade later, in the late 1950s, Nolan would revisit the subject of war in a major series inspired by the story of Australia’s disastrous Gallipoli campaign. He worked on the project off-and-on for the next two decades and produced hundreds of images. It might be the best least-known work of Nolan’s fecund and celebrated career.

Nolan’s Soldiers (1959). Australian War Memorial

Unlike Colonel Treloar, Nolan wasn’t interested in historical accuracy; he wanted to get at something truthful and universal. Nolan’s Gallipoli series is full of arresting images. Diggers are sent twisting and turning by shell bursts. Shadowy figures fight to the death with their bare hands. Doomed men frolic in the Aegean. Drowned corpses bob and roll in the surf. The mad stare from Head of a Soldier is repeated many times on many faces. Though they are twentieth-century Australians, the subjects of these paintings could have been fighting side-by-side with Achilles at Troy.

In 1978 Nolan no doubt outraged the ghost of Colonel Treloar when he donated 252 pieces from the series to the Australian War Memorial. The extreme modernist deserter had made it inside the building. Today the collection — probably worth millions — lies safely in the AWM’s secure storerooms.

The story behind this donation, and the creation of the series itself, is a little-known chapter in Australia’s cultural history. At its heart is Nolan’s friendship with three other accomplished Australians: George Johnston, author of the Australian classic My Brother Jack; Johnston’s partner Charmian Clift, a writer and newspaper columnist; and Alan Moorehead, a war correspondent and non-fiction writer.

The quartet were all members of Australia’s Double War Generation. Born during, or just after, the first world war, their childhoods were dominated by the Great War and its aftermath, while their twenties and thirties were shaped by the Great Depression and the second world war.

Nolan might never have pursued his Gallipoli series without the influence of the other three. Or if he had, it may have been very different. What do you call it when painters and writers exchange ideas, and meet and talk and drink together? You call it the history of art.

Back in the 1920s an iconoclastic member of the student body at Scotch College endured his school’s annual Anzac Day ceremony with well-hidden ennui. Many years later, Alan Moorehead would write: “I think that we school children, in our secret hearts, became bored with all this as we got older… bored with the singing of Kipling’s ‘Recessional’… bored with the retired generals’ speeches, the crossed swords and the little glass box of medals hanging in the school hall, and the war paintings in the art galleries.”

This was blasphemy, and the young Moorehead knew it. Anything less than veneration for Australia’s “civic religion” — as the historian Ken Inglis dubbed Anzac — was deeply frowned upon at Scotch College. “Even now,” Moorehead would write as an adult, “I have the feeling that I am dragging a shameful secret out into the open.”

On this point, Moorehead was not exaggerating. As for so many other Australian families, Gallipoli had been a catastrophe for the Mooreheads. Alan’s uncle Frank had been killed in action during the famous landing; another uncle, Harold, had survived a Turkish shell blast but lost his right leg and right arm.

While Moorehead was keeping his renegade views on Anzac Day to himself, elsewhere in Melbourne two other young Australian boys were also growing up in the shadow of the Anzac legend. In Elsternwick George Johnston spent the war waiting for the return of his father John, who served in Gallipoli and on the Western Front. Johnson’s mother Minnie worked as a nurse, caring for maimed veterans.

Many of these damaged men stayed with the Johnston family during the war. One of them, Bert Thornton, who had lost a leg in France, eventually married George’s sister Jean. As they wore out, Bert’s obsolete prosthetic legs were discarded in a pile behind the hallway door. Johnston’s childhood home was a sort of living memorial to the horrors of the war.

In nearby St Kilda, Nolan’s childhood was also suffused in the Anzac legend. His father Sid enlisted in 1916 and became a military policeman. As a young boy Nolan remembers reading The Anzac Book, a collection of poems and drawings written and illustrated by the “Men of Anzac.” Its famous cover picture, drawn by the soldier artist David Crothers Barker, succinctly conveys the Anzac story that most Australians in 1916 would happily accept; it was all about heroic Australian Britons fighting for the British Empire under the Union Jack.

Inside the book, the young Nolan would also read the following jingoistic doggerel, “The Trojan War, 1915”:

Homeric wars are fought again.

By men who, like old Greeks can die,

Australian back-block heroes slain,

With Hector and Achilles lie.

For these three young boys, the place names of Gallipoli — Suvla Bay, Achi Baba, Chunuk Bair — were as familiar as the tram stops of Melbourne. As Nolan once explained: “You grew up with Anzac, not so much a fact of life: it was part of one’s existence.”

In 1926 Moorehead began a law degree at Melbourne University. In the middle of his final exam he was gripped by an epiphany that must have bewildered his parents: he didn’t want to be a lawyer after all. He put down his pen, got up from his desk, and left the exam room; then he caught a tram straight into town, went to the Herald and Weekly Times building, and asked for a job.

After a few years as a journalist, this impulsive young man became restless again. The world was heading towards disaster, and he wanted to report on it. Moorehead left Melbourne in 1936 to try his luck on Fleet Street. His mind was on the war to come, not on the dusty rituals that commemorated the past war. “I must admit,” he wrote later, “that soon after I left Australia… the whole elaborate Anzac legend vanished utterly from my mind.”

The second world war made Moorehead famous. Writing for the Daily Express, Britain’s largest-selling newspaper, he became one of the world’s most celebrated war reporters. He covered the Desert War in North Africa, the invasion of Italy, and the final defeat of Germany from the Normandy landings to the fall of Berlin. Clive James considered him “a far better reporter on combat than his friend Ernest Hemingway.”

An untitled Nolan painting of Gallipoli figures in battle amid shellfire (c. 1962). Australian War Memorial

After the war Moorehead became a regular contributor to New Yorker, as well as writing general histories and travel books that became international bestsellers. By the 1950s he was the most widely known Australian writer on earth.

Moorehead began work on a general history of the Gallipoli campaign in 1954. At first glance it seems a quixotic choice of subject. Weren’t there plenty of interesting stories to tell about the war that had just recently ended? Why would a story that so bored him as a child make for a good yarn now? But the more he researched the story, the more haunted he became by it.

Moorehead realised his research would be incomplete until he visited the scene of the disaster. In the northern winter of 1954, he travelled to the Imperial War Cemeteries at Gallipoli. As he was ferried across the Dardanelles by motorboat to the land of the dead on the other side, he became aware that the short trip was redolent in history and myth. It’s the stretch of water Leander is said to have swum to visit his lover Hero. It’s where Xerxes, the King of Persia, built a bridge of boats to enable his invasion of Greece in 480 BC. And not far away is the site of Troy, the battlefield of Greek legend recounted in Homer’s Iliad.

When he finally set foot on Gallipoli itself, Moorehead encountered emotions he’d not expected.

There is a sense of timelessness about the Gallipoli Peninsula. Nothing very much has happened there since 1915. After the last battles were fought, silence descended on the place, and although there have been occasional earthquakes, it remains pretty much as it has always been — a simple farming countryside dotted with a few poor villages and fishing communities… [E]verything evokes the past, even the local shepherds; as they stand in the fields, swathed in tentlike goatskin capes, they look like figures in a classical landscape.

As his guide, a Turkish officer, lectured the defenceless Australian about the intricacies of the campaign, the boyhood cynic now grown to manhood found himself swept up in a reverie.

While I was waiting for the interpreter to translate, I would look at the lizards scuttling… and, beyond them, at the silver cloud of the olive trees, the heather on the cliffs and the sea. There seemed to be some stereoscopic lucidity in the air that brought all these things into one plane, so that the fisherman’s caique with red sails drifting by in the bay appeared no further away than the lizard on the wall; one felt one could reach out and touch either of them.

The veteran war correspondent admits that his feelings towards Anzac had shifted decisively.

Not unnaturally, in this atmosphere I found that my interest in the campaign had advanced through one more stage, that it had developed from legend, through history, to the point where it almost seemed to have become a personal experience of my own, and the sense of boredom it had produced in me as a child was quite gone.

Moorehead is inspired to make one final stop on his tour. “We found the grave easily,” he writes, “a plaque in the ground no different from the others, but still moving to me, since it had my surname on it.” It is, of course, the gravestone of Frank McCrae Moorehead, his long-dead uncle.

Moorehead wrote about his Anzac pilgrimage in a piece for the New Yorker called “Return to a Legend” in April 1955. Note: that’s not “of” but “to.” Throughout most of 1955, he hunkered down on the Greek island of Spetses, south of Athens, to write his book.

As you might expect from a war reporter who filed copy from the frontline, Moorehead was a speedy writer. His Gallipoli, published in 1956, was a commercial and critical success. Moorehead didn’t know it at the time, but his writings on the failed campaign — particularly his New Yorker article — would plant a seed in the imaginations of three other Australians.

In November 1955 Nolan left grey-skied London for the sunlight and stimulation of the Greek island of Hydra. Much had happened to him since his days at Heide. He’d moved to Britain, where his career was floating ever upward on a rising tide of artistic and commercial success. Most importantly, though, he had married John Reed’s sister Cynthia, a former dancer who had become a travel writer. The marriage, seen as a betrayal at Heide, was the final blow that toppled Nolan’s relationship with the Reeds irretrievably into a ditch.

Living on the island were his friends and fellow expatriates, the novelist and journalist George Johnston and his partner Charmian Clift. Clift was the youngest of the quartet. Born in 1923, she joined the Australian Women’s Army Service during the war and became an anti-aircraft gunner. Like many other women, the war offered her opportunities that might have been denied her in peacetime. She became an officer, a journalist, and began to fulfil her greatest ambition: to become a writer.

Clift and Johnston are perhaps the best-known of Australia’s literary couples. They had scandalised postwar Melbourne when Johnston, a respected journalist and, like Moorehead, a famous war reporter, left his wife and daughter for the much younger Clift. Both were romantics who pursued the writing life with little regard for the poverty and strains it inflicted on them.

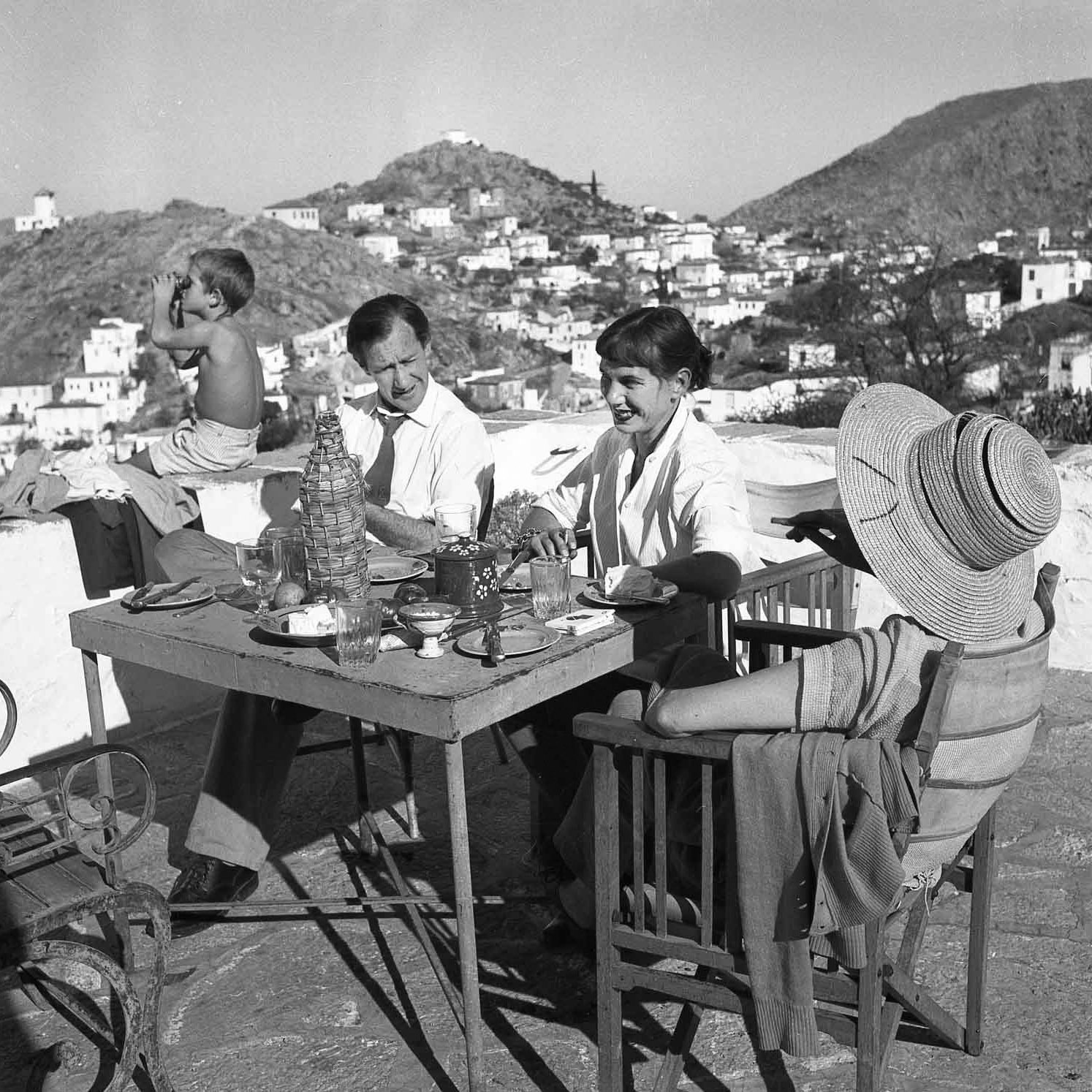

After several years in London, where Johnston worked for Australian newspapers, the couple grew frustrated with their easeful, metropolitan lives. They wanted to write books and needed somewhere cheap to live. Nolan played a small part in their plans. In London he had introduced them to a friend of his who extolled the virtue of Hydra as an ideal retreat for writers. They arrived in 1954 with their two children, Shane and Martin, and two new typewriters. A third child, Jason, would be born on the island.

With only a handful of English-speakers on the island, the two Australian couples are soon seeing a lot of each other. All through that winter and spring, after a day of writing and painting, they would meet in the backroom of the Katsikas general store or their other favourite haunt, the Douskas Taverna. As Johnston later wrote, “When the retzina circled and wild winter buffeted at the shutters of the waterfront taverns, we would talk far into the small hours.”

Inspired by his reading of The Iliad and Robert Graves’s The Greek Myths, which had been published to great acclaim in 1955, Nolan had started a series of works based on Greek mythology. But the project was frustrating him. “In a rare outburst of emotional passion,” Johnston recalled, he “flung his sketches down and cried, ‘You can’t paint it! You need metal and a forge; it’s got to clang!’”

By the end of his sojourn on Hydra, the hardworking Nolan had nevertheless created a significant body of work. In her book Peel Me a Lotus, Charmian Clift has a character based on Nolan — a painter she calls Henry Trevena — display his artistic haul from a season spent on the island:

In the studio Henry had spread out his winter’s work for inspection: five hundred small sketches in oil paint on the stiff white sheets of heavy art paper that he buys in bundles of a thousand at a time. The islands are there, the rocks, the goats, the spikes, the thorns — Greece actual. But most of the studies are concerned with Greek myth, browbeaten into tractability… The sketches are terribly impressive. It occurred to me, not for the first time, that Henry might well turn out to be one of the really important artists.

At some point during Nolan’s stay on Hydra, Johnston showed the painter Moorehead’s New Yorker essay. Nolan was particularly intrigued by the connections Moorehead made between Greek myths and the Anzac story. On his trip to the Anzac peninsula, Moorehead had also visited the site of Troy, which is not far south of Gallipoli, on the Asiatic side of the Dardanelles:

Just at first, it is difficult to evoke a picture of the past from the meandering diggings in the brown soil, and the vision of Helen of the lovely hair is lost somewhere in the rocks. But the Scamander still flows, the earth is the same earth that was kicked up by the chariots of Hector and Menelaus, and Mount Ida, looking detached and serene under its snow, cannot have altered at all.

For Nolan, Johnston later wrote, “It was like unlocking a door.” According to Nadia Wheatley, author of The Life and Myth of Charmian Clift, “It would take Nolan another few years to get the ideas onto canvas, but this was the genesis of his Gallipoli series.”

All his career Nolan relied on travel to stimulate his imagination. He rarely painted en plein air but he never painted a landscape he hadn’t visited. To produce the final work, he made sketches or relied on his eidetic memory. In his later, financially comfortable years, he owned a Manor House on the Welsh border called The Rodd. “I’m very fond of it, except I don’t paint it,” he explained in a 1984 interview, “I sit down and look at the snow and paint Ayers Rock.”

As the Anzac story began to percolate in his mind, Nolan realised that he would have to make a pilgrimage to Gallipoli, just as Moorehead had done.

In late September 1957, visiting Clift and Johnston in Hydra, he noted in his diary: “Delighted to see George & Charm. In evening talk about Anzac Gallipoli and Alan Moorehead’s book. Confirms my decision to do Anzac paintings & go to the Dardanelles.” The next day he wrote: “Hydra. Swimming. Decide paint large picture of Australian soldiers swimming at Anzac Cove.”

Within a month Nolan is in Gallipoli. As he later recalled:

I stood in the place where the first Anzacs stood, looked across the straits to the site of ancient Troy, and felt that her history had stood still. Here and there I picked up a soldier’s water bottle or some other piece of discarded equipment… I found the place on top of the hill where the Anzac and Turkish trenches had been only yards apart and the whole expedition balanced between success and failure. I visualised the young, fresh faces of boys from the bush, knowing nothing of war or of faraway places, all individuals, and suddenly all the same — united and uniform in the dignity of a common destiny.

Before he left Turkey, Nolan sent a postcard of Troy to Clift and Johnson back on Hydra: “Here it is that famed spot. We took a taxi there. Got to Anzac today so the record is complete. Thought of you both. Love Sid.”

The paintings and drawings Nolan created in reaction to this intense period of conversation, research, contemplation and pilgrimage would be unlike any other art produced in response to the Anzac Legend.

Beaten down by money troubles and ill health, Johnston and Clift retreated to England in 1961. It was to be a sanctuary from their worries; instead, it was a disaster. They missed the Greek sun. They failed to find well-paid work. Their children weren’t happy in school. But there was one bright spot: Johnston got to visit Nolan at his house in the London suburb of Henley and for the first time saw some of the outcomes of those drunken late-night talks on Hydra. Then their old friend came through with some tangible help. He encouraged them to return to Hydra, and sent them an art book with £5 notes interleaved between the pages.

Once back in Hydra, Johnston began work on the book that would solve his family’s money problems and make his reputation. Nolan’s biggest gift to Johnston, it turned out, were those same late-night retzina soaked talks back in 1955–56. Just as Johnston inspired Nolan, the painter also inspired the writer. As Nadia Wheatley explains, “If Nolan saw a way to fuse two potent myths [Anzac and Troy] and present the old story in a new and Australian light, a door had also been nudged open for George Johnston.”

The discussions about Gallipoli on Hydra encouraged Johnston to write a semi-autobiographical novel that would become My Brother Jack. It tells the story of Johnston’s avatar, a character called David Meredith, from his childhood during the first world war to his adult life as a journalist. The novel is about many things — ambition, masculinity, betrayal — but at its heart is a theme that was new to Australian literature at the time: the disastrous impact of “shellshock” — or what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder — on returned servicemen and their families. When My Brother Jack was finally published in 1964, it struck a resonant chord with Australia’s Double War Generation.

As Nolan pursued his vision of Gallipoli, he finally met the man whose ideas kicked the project into motion. In January 1960 Nolan contacted Moorehead in London; a few months later they met for dinner. As the historians Paul Genoni and Tanya Dalziell note: “Nolan and Moorehead may not have met in the Aegean in 1955, but they were destined to become close friends.”

According to Nolan’s biographer Nancy Underhill, the friendship between Nolan and Moorehead led to an important “intellectual interchange” between the two men. Moorehead was prompted to write about the Burke and Wills expedition by Nolan’s series of paintings on the doomed explorers. He published Cooper’s Creek in 1963. Later, Nolan’s second attempt at painting a series about the duo was influenced in turn by Moorehead’s book.

In January 1964 the two men travelled together to Antarctica for eight days. While Moorehead worked on an article for the New Yorker, Nolan made sketches for what would become his Antarctica series.

Nolan’s Gallipoli series got its first dedicated showing in 1965, when 145 paintings and sketches were exhibited at the Qantas Gallery in Sydney to coincide with Anzac Day. As Nolan explained in an interview, the works had been bubbling around in his head for some time:

And that is how I came to paint the series. Not then and there, and not all at once. But after I had thought about it in places like Hydra, in the Greek Islands, and Egypt, and Kenya and Ethiopia, and Australia and Antarctica, and London. I let the paintings come along as they wanted to.

As Nolan once said about his artistic output: “five minutes in the making, five years in thinking.”

Nolan visited Clift and Johnston on Hydra for the last time in 1963 to discuss the cover art he was designing for My Brother Jack. Just as he once gave them money to return to the island, Nolan now encouraged them to return to Australia.

Life on Hydra was becoming increasingly difficult for the couple: Johnston’s health was deteriorating due to tuberculosis; both were drinking heavily; Clift had become involved in extramarital affairs. With the imminent success of Johnston’s new novel, it might have been their best — and last — chance to return home. Nolan sealed his argument by burning some eucalyptus in an impromptu smoking ceremony: “He put a match to them and burned them and held them under our noses,” Clift later wrote, “and I was ready to cry with longing for the spiky wild strange grey bush, tunnelled with harshness and silence.”

Johnston and Clift returned to Australia with their children in 1964. To Johnston’s delight and relief, My Brother Jack was quickly and widely lauded as a classic of Australian literature, winning that year’s Miles Franklin Award. Two years later it was made into an ABC TV drama with a script by Clift. Johnston went on to write two more books in a trilogy about his alter ego, David Meredith: Clean Straw for Nothing (1969), which also won the Miles Franklin Award and then, posthumously, the unfinished A Cartload of Clay (1971).

In a diary entry written in September 1987, Nolan jotted down the following: “Remember that Alan Moorehead was going to write a book on the sacred lotus. Also, on the Sahara. Also, on the whalers who went from Nantucket to Tahiti, Antarctic, Australia, Peking: returning three years later to their wives.” If you know the context, it is a poignant memory of his old friend.

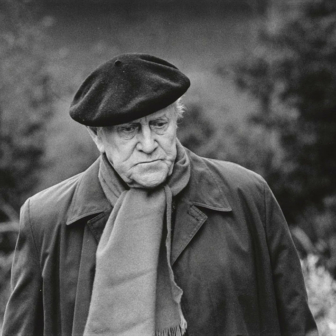

Moorehead had suffered a stroke in December 1966 that left him unable to write or speak with any skill for the rest of his life. For the seventeen years until his death in September 1983 — four years to the month before Nolan’s diary entry — he was pretty much incapable of working.

What Nolan was remembering, of course, was all the work Moorehead might have produced if he’d still been able to bang out a sentence on a typewriter. In July 1979, to compound the tragedy, Moorehead survived a car accident that killed his wife and primary carer, the journalist Lucy Milner. The purgatory of this energetic and vital man’s last years is hard to imagine.

In 1967 the Art Gallery of NSW held a major retrospective of Nolan’s work. He and Cynthia returned to Australia to attend the exhibition, and Nolan began work on a biographical documentary for the ABC called This Dreaming, Spinning Thing. The ABC filmed Nolan as he travelled around the country, revisiting places he’d lived and worked. As an old friend, Johnston was commissioned to accompany Nolan to conduct interviews and write the narration. Ill-health meant that Clift stepped in and conducted some of the interviews with Nolan.

The film’s director, Storry Walton, who also produced the 1964 TV dramatisation of My Brother Jack, tells me that the three old friends worked happily together on the project. “George’s script,” he says, “was respectful, reverent of [Nolan’s] talent and, I think, infused with his affection for the man, and the wonder for the kind of creative spirit in Nolan that George could never ever quite understand.”

When Charmian interviewed Sid for the film — out in the red centre, atop one of Kata Tjuta’s domed rocks — the two chatted like old mates who understood each other very well. “I never saw a hint of any bitterness or strain between them,” says Walton. “But it’s not to say that it didn’t exist. I saw the three of them for a sliver of time, when they were all bound together on a project.”

Under the surface, however, there is evidence that all was not well. As Nadia Wheatley explains: “Unfortunately, in all the planning, no one had realised that Sid’s affection for George — and to some extent Charmian — had considerably waned since the Hydra winter of 1955–56. With this film… would come the ending of the old relationship — at least from Nolan’s side.”

Also working on the project was a young Sue Milliken. A successful producer of TV and films, including the recent documentary Charmian Clift: Life Burns High, Milliken was back then a twenty-five-year-old production secretary at the ABC. She got to know the three quite well. “They all loved to talk,” she tells me, “and they were all charming.”

But Milliken also remembers that Cynthia Nolan, who she also got to know at this time, might have been the reason for the waning friendship. One night when Nolan was away filming, the two women had dinner together, and Cynthia confided to Milliken that she didn’t much like how Clift had portrayed a character based on her in Peel Me a Lotus. Ursula Trevena, the wife of the painter Henry Trevena, is described, for example, as “worn out” with a “ravaged” face, who “yawns and yawns as she hunches down in her coat and broods.”

Whatever the reasons, the relationship between Clift and Johnstone and the Nolans seems to have cooled somewhat by 1967.

Clift and Johnston’s relationship was also fraying and becoming more volatile. In July 1969, just before Johnston published Clean Straw for Nothing, Clift took a fatal dose of sleeping pills. Friends would reveal afterwards that Clift’s depression was partly generated by the book’s fictional depiction of her extramarital affairs during the Hydra years. After her death, Sue Milliken remembered something Clift once said to her: “Everyone says ‘poor old George’. No one ever says, ‘poor old Charm’.”

A year later, in July 1970, George Johnston died from the tuberculosis that had plagued him since living in Greece for many years on the borderline of poverty.

Nolan was not spared by tragedy either. In November 1976, Cynthia, his wife of twenty-eight years, was found dead in a room at London’s Regent Place Hotel — also from an overdose of sleeping pills. Nolan was deeply shocked. He professed to have had no idea about her mental state. Nor would he find any explanation in a farewell telegram she sent to him shortly before taking her own life. It declared cryptically: “Off to the Orkneys in small stages.”

So that’s the story of the series’ creation, but why did Nolan donate his Gallipoli paintings and sketches to the AWM?

In the confusion of the Anzac landing, many diggers died without ever reaching the shore. As they leapt over the gunwales of their steel lifeboats, weighed down by heavy boots and packs, they sunk into the depths, and never rose again.

Nolan’s Gallipoli Series contains many images of soldiers drowned in Anzac Cove. Nolan’s obsession with death by drowning goes back at least to his time on Hydra. The ever-observant Clift noticed that he was fixated by the story of Icarus, the boy who flies too close to the sun, and falls into the sea and drowns.

“Icarus occurs again and again,” Clift wrote, “The same haunting naked figure soars above fanged rocks and wide dark seas, sometimes just rising from the ground, sometimes a speck floating high against a burning ball of the sun, frail as a dragonfly.”

The myth of the drowned boy was always a key point of connection between Clift and Nolan. She owned a small Nolan painting of Icarus that for many years hung on the wall in her house on Hydra. On the island she also invented a parlour game based on the myth. She would divide people into Daedalus types (the careful engineer) and Icarus types (high-flyers and risktakers). George and Cynthia Nolan were Daedalus types; Charmian and Sid were born of Icarus. Nolan even turned the Icarus story into a sort of artists’ battle cry, urging his friends, in the face of rejection slips and the fear of failure, to “Fly then! Bloody well soar, why don’t you?”

Nolan was obviously engrossed by the Icarus story, but why did he transfer a version of this image from Greek myth into his Gallipoli series? He would have known that many Australians were drowned at Anzac — so the image is based on historical fact. But as we know, trifling facts were of limited interest to Nolan.

Back in 1944 when Nolan went AWOL, his patriotic parents must have been horrified and embarrassed by their son’s behaviour. Nolan claimed later that his father — the former military policeman — even threatened to tie his legs to a chair and jump on him; a punishment meted out to deserters during the first world war.

Like George Johnston, Nolan had a brother. Raymond Nolan, known in the family as Boy, was seven years his junior. He had been born in 1924, just a few months after the Australian champion swimmer Andrew “Boy” Charlton won gold at the Paris Olympics. To the pride of his parents, the younger Nolan turned eighteen in 1942 and promptly enlisted, becoming a sapper in the 15th Small Ship Company, and serving in the South Pacific.

On 20 July 1945, with the war almost over, Raymond was drowned when he slipped and fell from a boat into the harbour at Cooktown. A few weeks later, on 6 August, when the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the war was effectively over.

Nolan believed that Raymond’s death shortened his father’s life. It must have also exacerbated the distress both his parents felt about their eldest son’s dereliction of duty.

Nolan’s Gallipoli, panel 1 (1963). Australian War Memorial

The largest of Nolan’s works held by the AWM is a diptych simply called Gallipoli that features several ghostly figures struggling in water. It’s been described as “an aquatic vision of hell” and directly references Raymond Nolan and his father Sid. On the left-hand side of the first panel (above) is a portrait of the father and his son. Is the older man trying to save Boy? Or is Boy trying to protect his father?

When Nolan donated the Gallipoli series to the AWM back in 1978, he did so in the name of his brother Raymond. •