The exhibition Fit to Print, currently showing at the National Library in Canberra and viewable online in the form of a virtual walkthrough, comprises 150 photographs, expertly printed, mounted and framed, all of them selected from the 18,000 or so negatives donated to the Library by Fairfax Media in 2012. The entire archive, covering the period from 1890 to 1948, has been restored and digitised by library staff and is available to view on Trove, that triumph of Australian digital infrastructure which somehow never achieves the widespread acknowledgement it deserves.

To browse the full collection online is to scroll through Australian history in pictorial form, calling up hundreds of landscapes and buildings and, most evocatively, faces, some of them still well-known, many more once well-known and now largely forgotten, and yet more whose details were not recorded at the time and whose individual biographies are beyond recovery.

The anonymity of so many of the faces captured during the early days of photojournalism by photographers who have themselves, for the most part, faded into anonymity, is to heighten their representational nature. Curator Mike Bowers, himself an experienced photojournalist, has managed to retain that representational quality even while whittling down a vast and potentially overwhelming collection to a mere 150 images.

The recurring themes of early news photography are all there — people engaged in ordinary tasks, working hard, building things, relaxing, playing sport, doing something silly or odd. A mood of national optimism and resilience dominates, even — or perhaps especially — during the Depression and at other times when optimism was in short supply.

A splendid image captioned “Seven men pushing a car through water at the Gerringong motor races, New South Wales” (1930, below), by an unknown photographer, seems to sum up the relationship between nature and technology, as the men, trousers rolled up above their knees, band together to get the machine going again in the face of nature’s attempts to bring it to a halt. This photograph represents a much larger collection of images from the archive focused on collective effort, on groups of people pushing or pulling together to achieve a common goal.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

In contrast, relatively few of the pictures convey the darker side of everyday life. One such, “Two small children in Surry Hills” (1932, below), photographer unknown, seems by its relative rarity to stand out from the wall, distinguished by its frank confrontation with the reality of poverty, momentarily altering the mood. The two children of the title, dressed in raggedy clothes, their faces smudged with dirt, stare warily at the camera, unsure of what is in store.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

One of the few named photographers in the exhibition, Herbert Henry Fishwick (1882–1957), is best known today for his profound influence on the development of sports photography. It was Fishwick who in 1920 introduced the telephoto lens, which revolutionised how on-field action could be captured in close-up.

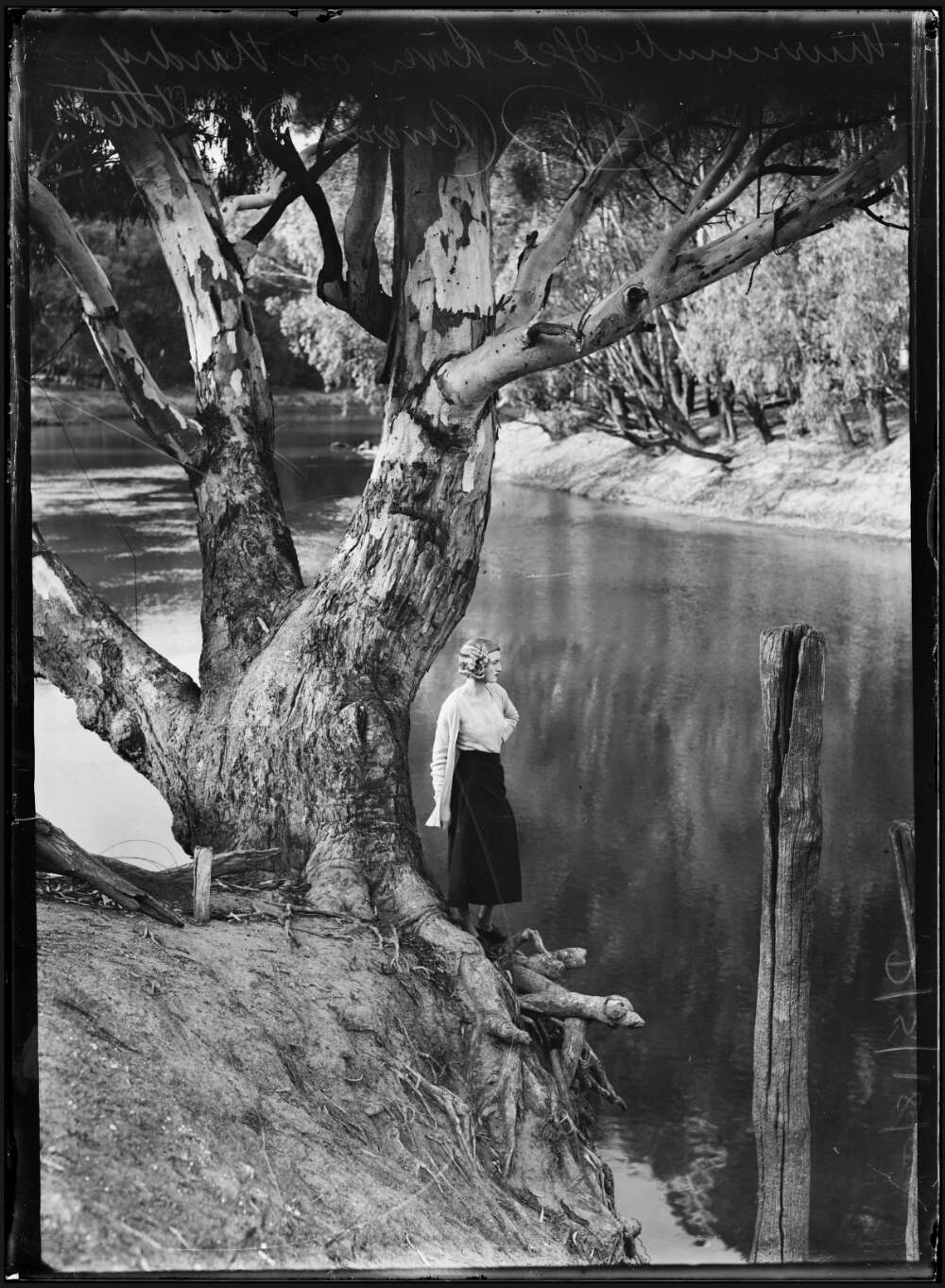

He also did a nice line in nature photography, as demonstrated by two highly painterly images included in Fit to Print. In “Woman beside Meroo Creek at Hardy’s Station, Yass” (c. 1929, below), a figure positioned in the lower centre of the frame gazes across the river to the far bank. The curve of her arm is matched to the curve of the tree trunk directly behind her, suggesting, in contrast to the image of the men pushing the car out of the water, a harmonious oneness with nature.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

Similarly, in Fishwick’s “Man on the bank of the Snowy River between Pinch River and Jacobs River” (1932), the man, placed in the left-hand band of the golden mean, looks across the water towards a large rock protruding from the riverbed. In both these images, the human figure is portrayed in a pose of calm contemplation, untroubled by the vastness of the landscape and the bulk of its natural forms.

Nature and the vastness of the Australian landscape are not typically presented as threatening but rather as a source of support. Just as the woman looking over Meroo Creek seems to be being protected by the tree behind her, so in an anonymous image to be found in the archive, “Policeman sitting beside tree writing home” (c. 1920s, below), the tree acts as a bulwark against his loneliness and separation from his family.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

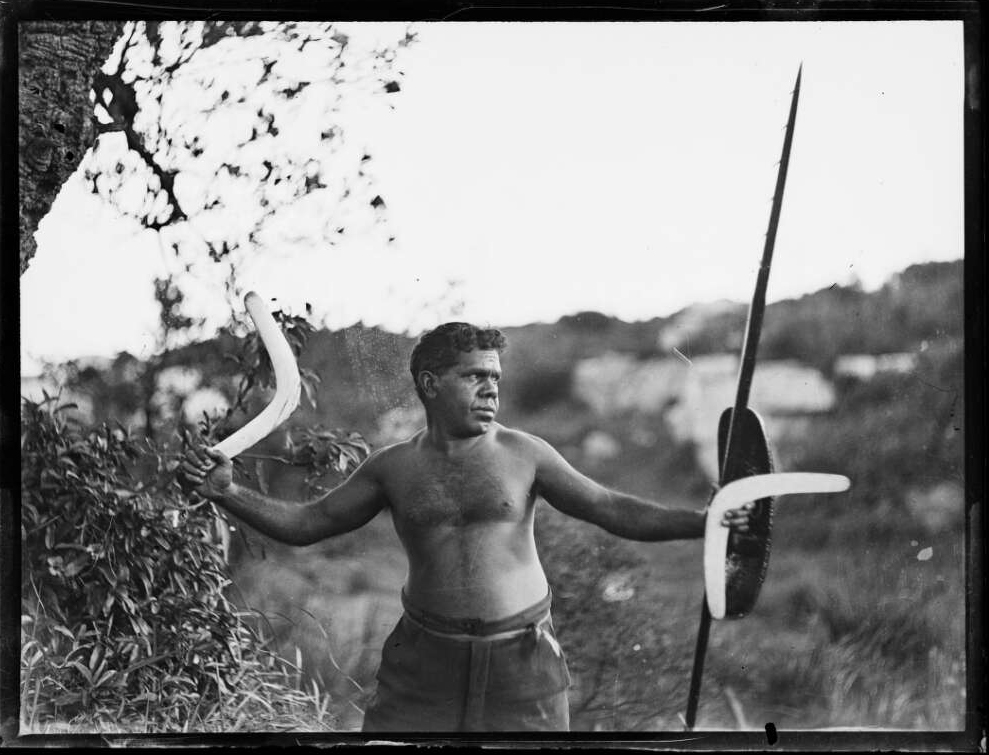

Indigenous people, who might have embodied much more convincingly this kind of relationship with the land, don’t appear in any numbers in the archive, leaving something of a documentary void. Once such photograph from 1933, of D’harawal activist and musician Tom Foster (below), chosen for the exhibition from the few available, demonstrates what can happen when a reliance on artificial placement of the subject becomes reductive. Forster is posed against a background of hills but, as if to cut him off from the natural world, the hills behind him are just a blur, while the obvious props he is holding, including two boomerangs, are in sharp focus, competing distractingly against the dignity of his expression and demeanour.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

The expressions on the faces in these early photos, whether wary or welcoming or merely curious, strike us now as highly self-conscious — not of the contemporary, selfie-conscious kind that displays familiarity with the presence of the camera and the protocols of performance — but with a frankness that is both revealing and, for the viewer, genuinely engaging.

A young woman poses with a parasol on Bondi Beach in 1930 or thereabouts, a night fisherman gazes intently at his catch one evening in 1920, a newly enlisted man (main photo, above) is farewelled at a station platform in 1915. These images, and many more like them, have qualities of both naturalness and staginess about them, the kind of staginess that can be present today only with an overlay of irony and knowingness on the part of photographer and subject.

As Bowers explains in the exhibition booklet, “while staging or intervention is largely avoided by photojournalists now, for those working in the early twentieth century the ability to manipulate a scene was essential.” Newspaper photographers “knew that subjects and props could… make a good image great.” The bulkiness of equipment, the complexities of using glass plate negatives, the cost of materials, all worked against the photographer acting spontaneously.

Yet in these images made while the camera was all the time increasing in popularity but still not nearly as embedded in the culture as it is now, the staginess can give rise to its own, paradoxical brand of naturalness, the subject often looking frankly at the lens or obediently at a prop to hand, sacrificing agency in deference to the photographer. Whether it is a group of children perched on a partially dismantled merry-go-round or soldiers laughingly astride a camel, the images convey a trust on the part of the subjects that the camera will see them as they see themselves.

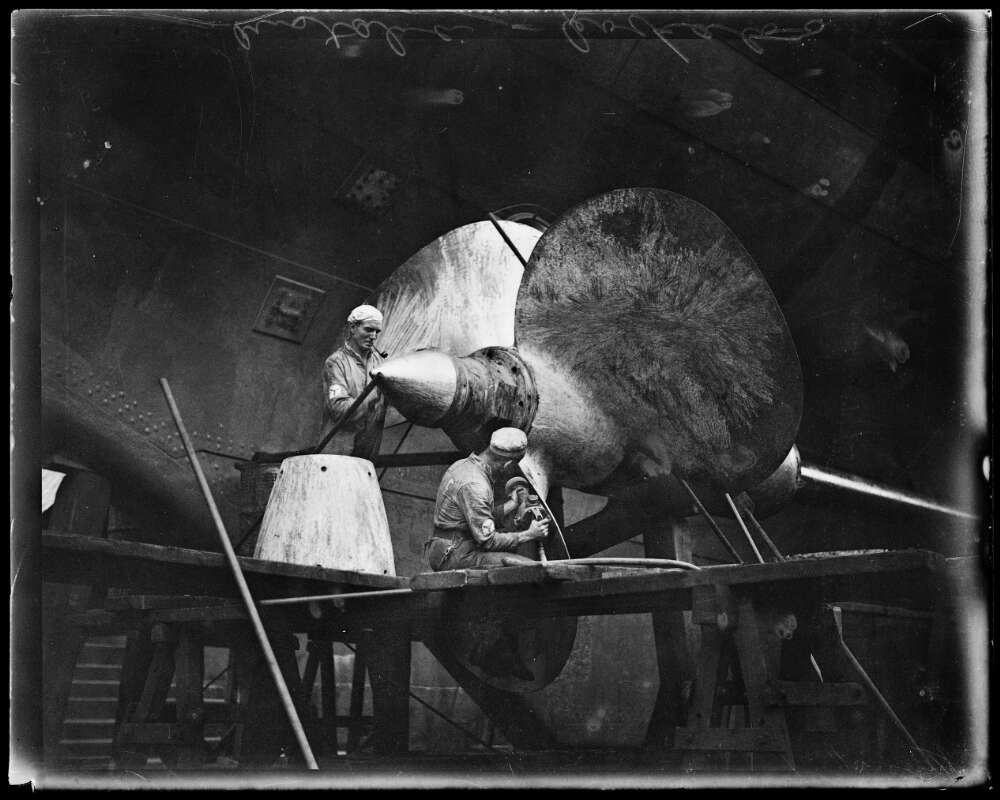

Inevitably, given that the curator looks for the best as well as the most representative, the process of selection by Bowers and the staff who assisted him results in images that satisfy aesthetic as well as documentary criteria. “Men working on the propellor of HMAS Australia at Cockatoo Island” (below), for example, taken in 1920 by an anonymous photographer, has the look of a Wolfgang Sievers, and an image of a technician working on an aircraft (c. 1931), again by an anonymous photographer, displays a similarly understated sophistication in terms of lighting and composition.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

This level of technical expertise combined with aesthetic instinct is not necessarily reflective of the entire collection of more than 18,000 images. But, if the viewer is prompted by the exhibition to take a closer look at the online archive, there are other rewards to be had. A rather splendid image of the great French tennis player Jacques Brugnon (below), for instance, delivering a mid-air smash in Sydney in 1928, leads the viewer to a surprising number of photographs of French tennis players, including one, tentatively identified, in which a group of men in suits raise their hats in the air.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

The question mark included in the caption to this image — “French tennis players [?] raising their hats” (c. 1920) is an example of the kind of laconic allusiveness that is characteristic of the archive captions generally. Just as most amateur photographers never quite get around to annotating their snapshots, to the frustration of succeeding generations, so these professional photographers, working under the pressures of time and their next assignment, leave the sparsest of notes before moving on.

This absence of background information encourages the instinct to speculate. In “Woman beside turtle and coral, New South Wales” (c. 1930, below), to take an instance at random from the archive, the woman of the caption sits at a table piled with examples of different kinds of coral. She looks directly at the camera, both shy and proud, her hand resting with proprietorial restraint on the back of a turtle, who looks anxious to be off. There is a story there, destined to remain frustratingly elusive.

Fairfax Collection/NLA

Neither does an image of “Mr and Mrs Alfred Frith, standing in front of a window” (c. 1929) give much away. They make a handsome couple. Mrs Frith wears a splendid cloche hat and Mr Frith, in a suit and homburg, is holding what appears to be his wife’s handbag close to his chest. Who were they? Stage actors, an explanatory note reveals, whose careers have faded into history and whose biographies are recoverable only in the sketchiest form.

Not all the images in the complete archive merit more than a passing glance. A picture of a palm tree doesn’t invite reflection, and one of a funnel web in a specimen tray is of specialised interest only. Chancing across “Beauish the greyhound with his trainer course side” (1932),” we do not feel compelled to linger.

In fact, for those impressed by the undoubted quality of the images that make up the exhibition Fit to Print, and by the obvious talent of the mostly unknown photographers, a closer examination of the pictures in the archive, for all their value to social and historical research, may prove to be, in aesthetic terms, something of a disappointment. An exhibition like this demonstrates why the curatorial function has moved from the background to the foreground in the cultural landscape, as the curator sifts on our behalf through the vastness of the visual database. •

Fit to Print: Defining Moments from the Fairfax Photo Library

National Library of Australia until 20 July 2025