Among Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s lecturing duties in Melbourne University’s history department, where she worked from 1938 to 1962, was a first-year course concerned mainly with the England of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and especially the English civil war. It was among her typed lecture notes for the course that I found this passage:

If I may be indulged for one moment in personal reminiscence I should like to say that I can date the exact moment when the sense of the past awoke in me. I had just finished my first year at this university — I was studying history, but it was just a subject like any other until in my first long vacation I went to Tasmania and visited the old penal station at Port Arthur. To me this very recent ruin was incredibly ancient and peopled by the dead. I have still — though wild horses would not drag it from me — documentary evidence in the shape of my first historical essay, to show the extraordinary impact of those few poor stones on my imagination. And when, many years ago, I came to write an historical work myself it was about convict Tasmania.

Kathleen’s foundational course in history could attract enrolments of five hundred students split into a daytime and an evening group. She must have taught thousands of students across her career and the impact she had on them was profound. Particularly memorable was her elegant presence, how she would sweep into the lecture theatre splendidly dressed and coiffed, pearls at her throat, often with a flower attached to her billowing academic gown: a rose, a carnation, or sometimes a camelia freshly picked from the garden in the Old Quad.

Her lectures were always carefully structured and so beautifully delivered that (unbelievable as it may seem in our own day) some students at the afternoon session returned for the repeat performance in the evening. Fifty years later many of her students claimed to remember whole passages from them.

Kathleen was on leave in 1947 when Ken Inglis took her course, so he had to endure the “scratch team” that filled in for her. But in 1949 he sat in on her lectures for “revision and inspiration.” He never forgot her quoting Thomas Rainborowe, who fought for parliament during the civil war: “The poorest he that is in England hath a life to live as the greatest he.” In those early years after the second world war, Inglis felt that this was what his generation’s postwar reconstruction was all about too.

By the early 1960s Kathleen’s “god professor” demeanour was looking rather affected in the eyes of students drawn from increasingly diverse backgrounds. Many were more amused than entranced. Although the era of jeans, T-shirts and student revolt had not yet arrived (Stuart Macintyre recalled twinsets and Fletcher Jones slacks during his student days at Melbourne in the 1960s), Professor Fitzpatrick must have seemed an emissary from another epoch to a lecture theatre of 250 eighteen-year-olds.

I like to picture the scene — the startled looks and the pens suddenly still — as Kathleen craved her students’ “indulgence” for her “personal reminisce.” This remote, ageing woman (she was actually in her mid-fifties) had been an undergraduate herself, apparently! She had sat, pen in hand, in the same lecture theatre at the same long wooden desks, as nervous and eager themselves.

She too had wondered if history was the right subject for her, until by chance she realised that it can be discovered not just in classroom and library but also out there in the world. Still, she confided, “wild horses” would not drag from her that first literary effort that was not a university assignment. Surely at that point everyone in the room must have immediately longed to read it; I certainly would have.

As it happens, the passing of years has given me the advantage because Kathleen did keep that student essay and it was among her personal papers transferred to the University of Melbourne Archives after her death in 1990. When I realised this, wild horses couldn’t have stopped me booking a flight from Canberra to Melbourne to read it.

It would have been simpler to have it digitised of course, but by then I was agog with curiosity as to what else I might find. Having years ago read Kathleen’s memoir, Solid Bluestone Foundations, published to wide admiration in 1983, I’d noticed that she is the sort of person who stays with you. I read her published correspondence with Manning Clark, Dear Kathleen, Dear Manning (1996) and was delighted when finally a full biography appeared, Elizabeth Kleinhenz’s A Brimming Cup (2013).

Once again, just recently, Kathleen popped into my line of sight while I was working on a piece for Inside Story on the historiography of Australian biography. I learned that for her 1949 book Sir John Franklin in Tasmania 1837–1843 she’d had to find and slog her way through prodigious quantities of primary source material because very little had been published about Franklin’s years in Tasmania. The book was Kathleen’s most sustained academic achievement, but I was disappointed to note that Kleinhenz passes over it in only a couple of pages.

Kleinhenz concludes her biography with the strange observation that not a great deal survives of Kathleen’s work as a research historian and writer. And yet Kathleen had published steadily throughout her career, and her papers at the University of Melbourne are full of notes and drafts and correspondence about her work. Among them, quite clearly identified, is an essay titled “Port Arthur,” neatly written out in her own hand. The only oddity is that the piece is initialled “J.D.O.” and not “K.P.” (for Kathleen Pitt, as she was then). Perhaps she hoped to publish it pseudonymously and the O was a reference to her maternal grandmother’s family, the O’Briens.

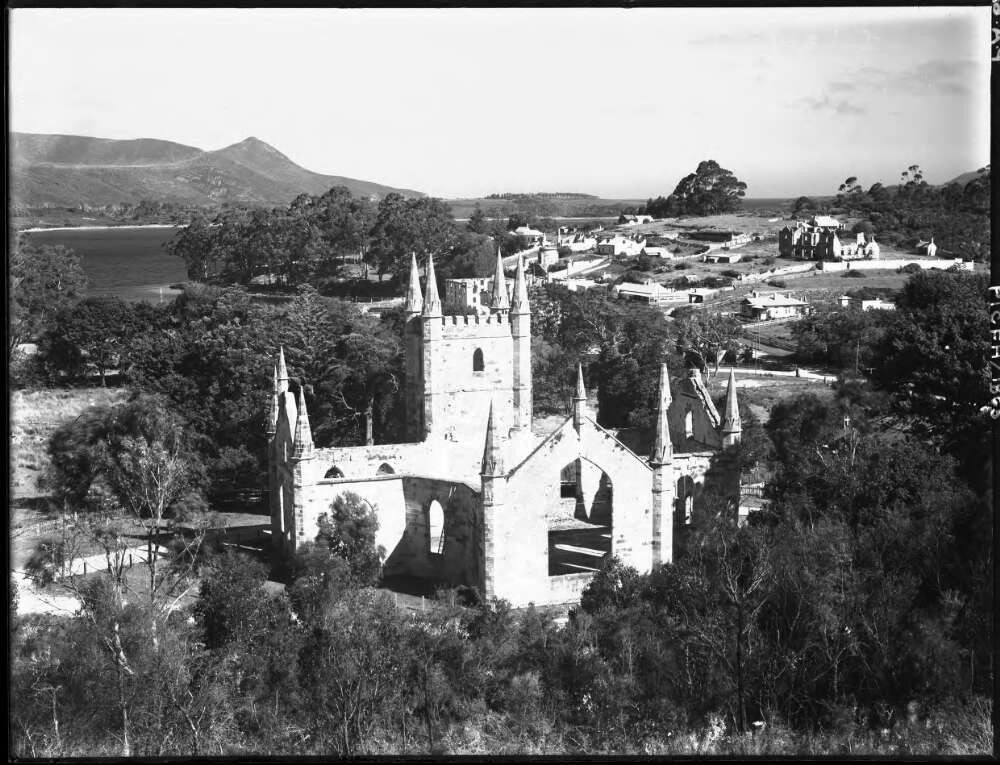

The Port Arthur visit occurred during a Pitt family holiday in the summer of 1923–24, and the young historian-to-be asks her reader to join her for an evening stroll through the site. She begins with “the stately church such as our own ancestors worshipped… in many an English village,” but which turns out to be an empty, ivy-clad shell. As we proceed past hawthorn hedges and old-fashioned English flowers, we notice a “deadly quiet” has settled on Port Arthur where once, “in the old days,” everything was “clutter and bustle and stir.”

Port Arthur photographed in the early 1930s by Frank Hurley. National Library of Australia

We pass the hospital, the penitentiary, the model prison (now known as the separate prison) and the guard tower. We even cross to the Isle of the Dead, where headstones mark the graves of soldiers and warders but one now “walks unknowingly over the dust of the unhonoured dead [of convicts].”

Kathleen would soon learn via the blue pencil of her English tutor at Melbourne, Muriel Berry, how to eliminate the purple passages to which she was prone, and her history lecturers helped leaven her colourful imagination with healthy doses of scepticism and detachment. But at this moment Port Arthur had her in its spell. She abjured the “fairy stories” spun by the site’s tour guides but fell for one herself when she wrote that the “Governor’s cottage,” as she called it, was the summer residence of the governor of Van Diemen’s Land. She thought it ironic that this personage would choose to make “this place of suffering his place of pleasuring.”

She goes on: “In this old deserted garden, and by this crumbling fountain weary of waiting many years now for the hand that shall set it play again, strolled once many a Vice-regal lady and resplendent military man.” Had she been able to resist invoking shades of Tennyson (“By this still hearth, among these barren crags…”) she might have realised how improbable this was. The government cottage was built merely to accommodate government officials and visitors to the settlement, and the colonial governor’s actual summer retreat was at New Norfolk, on the River Derwent northwest of Hobart.

In fairness, Port Arthur is difficult to write about. To be confronted by stupendous beauty and terrible pain in the same place is a challenge for anyone who goes there, especially after the events of April 1996. Many people are struck by quiet, as was Kathleen. In 1923–24 she wrote that although in the summer “great chara-banc [motor-coach] loads” of people pass through every day, to be rushed around by tour guides, “the quiet enters into them, and they make little noise to disrupt the prevailing calm.” She noticed a few visitors lingering among the crumbling ruins, and in the hush it seemed that “the spirits of the dead are not far away.”

It’s a mark of Kathleen’s strength, I think, that for the rest of her life she held on to her essay on Port Arthur. She kept it under wraps, certainly, but she was never embarrassed to allude to the awakening experience she’d had at Port Arthur. From my reading of her lecture scripts, I think she began including her “personal reminisce” in 1948, and was still including it, word-for-word, in lectures delivered in the early 1960s.

Underneath the cloak of formality Kathleen donned along with her academic gown every day there was a warm-hearted but also quite vulnerable person. She was, as she once admitted to her head of department, Professor Max Crawford, a “highly strung and nervous character, who only produces an effect of calm and confidence by a continuous act of will.”

Her academic career misfired twice. In 1926, having completed her first degree at Melbourne, she enrolled at Oxford in a second undergraduate degree. But there, lonely, unmentored, without a scholarship (her fees were paid by her father) and despite working herself to exhaustion, she came away with a second-class degree, not a first. The second setback was a brief and disastrous marriage in 1932 to journalist and future historian, Brian Fitzpatrick. She emerged from the divorce determined to regain her career and independence. Her appointment to Melbourne’s history department in 1938 set her back on track to the life she had always wanted.

It also meant that she could start to plan a research career, and perhaps then she felt the time had come to dust off her essay on Port Arthur to see where it could take her. She was quite certain by then, I think, that her research methodology would focus on primary source material. Ernest Scott, professor of history at Melbourne during her undergraduate days, had inspired this passion. In his lectures, the people of the past had become much more real to her than in school textbooks and he had done it by quoting from primary sources.

Very soon Kathleen selected Sir John Franklin’s governorship of Tasmania as her special interest. In 1939 she published an article about him in the journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, based on archival material newly transferred to the Mitchell Library in Sydney. Few academic historians were interested in Australian history then. Scott had been an exception, but sadly for Kathleen he died in 1939 just as she was restarting her career.

Sir John Franklin in Tasmania was a long book with simple ambitions. Franklin was famous in the history of polar exploration but his six-year governorship of Van Diemen’s Land had been given scant attention by biographers. This had left unrefuted a long-held belief that his Tasmanian years had been a failure. Kathleen countered with the argument that he had struggled with circumstances beyond his control, and she furthermore contested the notion, put about by his enemies in Van Diemen’s Land, that his government was subject to “petticoat” interference by his wife, Lady Jane Franklin. By bringing gender relations so firmly into her narrative, Kathleen became a pioneer of women’s history in Australia, although it was more than fifty years before her contribution was recognised as such.

Impeded by wartime interruptions and by a heavy load of university teaching and administration, her book took ten years to write. Her main sources were the official records, kept in Hobart, of Franklin’s administration, which included copies of despatches sent to London as well as various departmental records and police and convict records. She supplemented these with an extensive reading of early colonial newspapers.

Kathleen consulted a range of personal papers as well, some held in libraries, others still in private hands. A breakthrough came in 1947 when she was granted leave by her department to travel to Cambridge to read the papers of Lady Jane Franklin held at the Scott Polar Research Institute.

I often think of her in the basement of the old Supreme Court building in Hobart confronted with shelf after shelf of the unsorted and unlisted records of Franklin’s administration. During many a lunchtime she must have sat alone with her sandwich on a bench in the adjacent park, Franklin Square, named after her hero, looking up at his statue and wondering if it was all worth it.

To my knowledge, no historian at that time, not even Manning Clark with his books of documents on Australian history, was sweating at the coalface like Kathleen. Clark was mainly working with published primary sources, not archives, and in any case, he had his wife Dymphna to assist.

Kathleen’s narrative did sink sometimes under the weight of all that archival material, leaving obvious errors for academic reviewers to find. Some of the reviews caused her great distress, but in Tasmania the book was well-received. Sir John and Lady Jane had always been fondly remembered there. Many local readers might have been pleased that it begins not with a dreary academic exposition of her central thesis about Franklin, but this: “The heart-shaped island of Tasmania hangs like a pendant from the mainland of Australia, larger than Ceylon and smaller than Ireland, the last outpost of Australian before Antarctica.”

She continues with a description, beautifully done (because she had long-ago learned how to write crisp English prose) of the island’s physical features: its mountains, its plateaus, its climate, its rivers and rainfalls. She understands the relationship between physical environments and human cultures, just as historians do today.

In her several trips to Hobart for Franklin research it’s unclear whether Kathleen got to Port Arthur again. She made friends with some historians in Hobart and one of them might have taken her there in their car. “Port Arthur is an enchantingly lovely place,” she writes in her book, “but one that every visitor is glad to leave, because here man soiled in a few years the secret and untroubled beauty that nature had sheltered for a millennium.”

Kathleen also recounts a distressing story of a twelve-year-old boy, William Pearson, brutalised at Point Puer, the prison for boys at Port Arthur. She says Pearson’s police record was one of the “most horrible documents” she had ever seen. Other than that, she remains detached and impersonal in her analysis of the administration of convicts at Port Arthur. Once bitten twice shy, perhaps.

In a tribute to Kathleen published in the Melbourne Historical Journal in 1964, Ken Inglis (who, after graduation, was a junior colleague of Kathleen’s at Melbourne for a few years in the early 1950s) admired Kathleen for wanting to make the study of the past a “personal encounter.” Her Franklin book demonstrated her ability to evoke visual images. “Here… is a historian using her eyes,” he declared. Her readers can see the places and the people as they are too seldom allowed to in the works of academic historians.

The year 1949 was an important one for Kathleen. Franklin was finally published and she had just been promoted to associate professor, the first woman in a non-scientific field to attain that rank in an Australian university. In January 1949 she achieved another first when she was made president of the history section of the 1949 ANZAAS meeting. No other woman had ever been given the role.

As president she was expected to give an extended address (a “keynote,” we would say), and the topic she chose was “The Role of Imagination in History.” The conference was held in Hobart, and how immensely satisfying it must have felt, riding a wave of success after all her hard work, to stand in front of an audience where, twenty-five years previously, she had first begun to exercise her own historical imagination.

Her lecture, later published in the conference proceedings, was a long mediation on what she had learned in those years from the work of many historians and thinkers, and from her own experience. Imagination is not an ornament to history, she said, but belongs to the very structure of historical knowledge. It is not free to roam at will but is bound to the evidence. It must not conflict or go beyond evidence except as speculation, which will be indicated as such. Anything can evoke the “authentic voice of the past,” not just archival records but objects, works of art and historical places also. And here Kathleen inserts her personal reminiscence about Port Arthur, telling her audience that the encounter had made her a lifelong student of history.

I can’t say for certain that Kathleen Fitzpatrick was the first Australian historian to write about imagination in history, but it’s possible. Nor do I know if she was aware of William Faulkner’s famous remark that the past is never dead, it’s not even past. But she says something similar when she notes that we all belong to our own time and we must cultivate our modern consciousness.

Any account of time past, she muses, is at best only an approximation of what happened. “The most beautiful piece of historical interpretation is only the tale told by a historian.” •