Riefenstahl, one of the highlights of this year’s German Film Festival, is a rich, engrossing work of documentary excavation and analysis. Director Andres Veiel uses archival material to produce a revealing portrait of a subject working hard to shape her own image. Riefenstahl speaks volumes about the figure at its centre, but it is also a salutary reminder of the nature of media manipulation and the appetite of the media and the public for narratives of redemption or self-justification.

Veiel makes sparing use of voiceover narration. He assumes viewers have a basic awareness that Riefenstahl directed Triumph of the Will, the account of the Nazi party’s 1934 Nuremberg congress that begins with the figure of Hitler descending as if from the clouds to a waiting city.

Riefenstahl courted public awareness right up to the end of her life. Beginning in the 1970s, she waged a persistent, single-minded campaign to reposition herself, to rewrite her biography and distort history. She worked hard to project herself as an artist, a pioneer and a groundbreaking documentary-maker, and to skirt around suggestions of complicity in or knowledge of the actions of the Third Reich.

As we see in Riefenstahl, she presented her case from various, sometimes contradictory angles. She was “commissioned” to make Triumph of the Will; she was simply documenting, just doing a job. “Back then, the whole world was enthralled by Hitler,” she says. On the other hand, she was hired because she was an artist. In another line she pushes in various ways: art is one thing, politics is something else altogether. And “in all the films I made, I was always captured by the beauty of the subject.” Faced with anything that looked like an inconvenient fact, she simply denied it.

Riefenstahl, who died in 2003 at the age of 101, was not only a canny self-promoter; she was also responded litigiously to critics or journalists who challenged her. Veiel shows a clip of her throwing open the door to a cupboard full of lever-arch files — records, she claims, of more than fifty libel cases she had pursued.

Although this is not something Veiel explores, a section of the film community was prepared for a time to take her at her word: to focus on her achievements (such as the technical and artistic innovations of her film about the 1936 Berlin Olympics) and downplay her role in promoting the Third Reich. The first Telluride Film Festival, in 1974, honoured her alongside Gloria Swanson and Francis Ford Coppola, and although there was controversy over the choice, the New York Times reported that she was “acknowledged by critics to be a consummate artist.” Triumph of the Will is merely a newsreel, the paper quotes her as saying, though “different from normal newsreels, because I made it artistically.”

She made no more feature films after the second world war, reinventing herself as a photographer and publishing essays and coffee table books chronicling the time she spent among the Nuba people of Sudan. There are some telling examples in Riefenstahl of the difference between how she talked about this work and how she can be seen interacting with her subjects.

Veiel includes many examples of media coverage in Germany and internationally. He uses extracts from selected documentaries about Riefenstahl and the TV interviews she gave, as well as unaired material from those recordings. The latter footage includes moments in which she takes issue with questions or framing, sometimes quite aggressively. She was clearly a micro-manager. Old habits die hard: in her late nineties, being interviewed for a docudrama about her friend, the Reich architect and armaments minister Albert Speer, she checks herself in a hand mirror and suggests lighting angles.

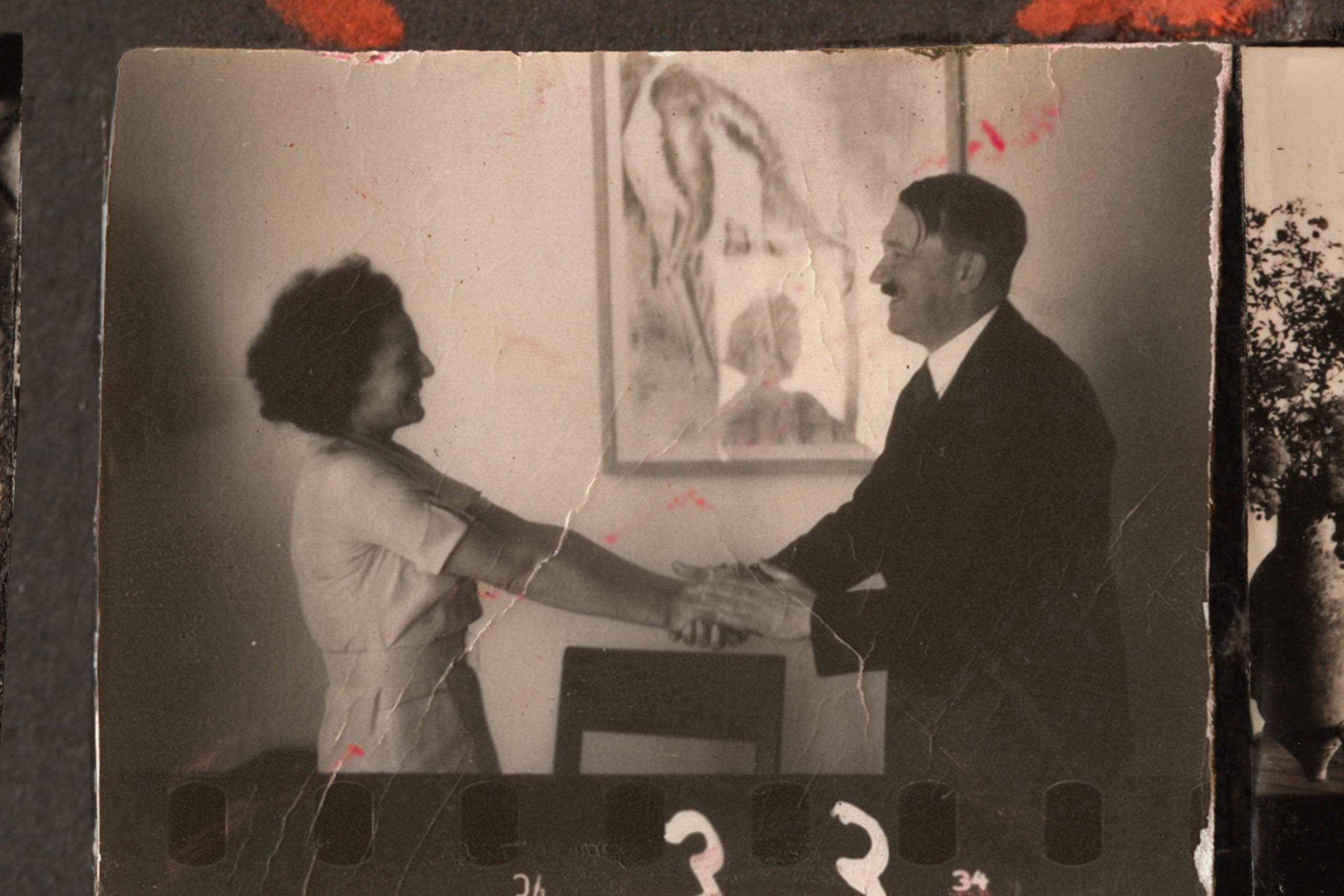

Veiel was the first filmmaker to have access to Riefenstahl’s extensive personal archive, consisting of more than 700 boxes of material. Some, we are told, are carefully arranged, some partially sorted and others seemingly gathered at random. Much of what we see and hear testifies to her self-absorption and apparent compulsion to document every aspect of her life. Veiel draws, for example, on recordings she made and kept of telephone conversations with journalists, members of the public and publishers, and with Speer. She asks his advice about publishing her memoirs, and how much to charge for media appearances.

Generally without labouring the point, Veiel trusts his audience to make connections and identify contradictions. He also reminds us, from the very beginning, of the physical, material qualities of the archive. And he plays from time to time with photographs and footage of Riefenstahl, using zoom, close-up and slow-motion techniques that heighten the sense of performance.

Sometimes he simply employs straightforward juxtaposition. Triumph of the Will, Riefenstahl assures an interviewer, was all about “peace” and “work,” and made “no mention of racial theory.” Veiel cuts to a moment from Triumph of the Will in which Julius Streicher (politician and publisher of the virulently anti-Semitic Der Stürmer) proclaims to the assembled crowd, “The people that does not protect the purity of its race goes to seed.” (Streicher’s speech was one of several that Riefenstahl re-recorded, weeks after the event, because the footage was faulty.)

One of the most memorable examples of Veiel’s thorough, all-embracing approach concerns an appearance Riefenstahl made on a German talk show, Je Später der Abend, in 1976. She is seated on a couch in front of a studio audience; next to her is Elfriede Kretschmer, a one-time factory worker of around her age from Hamburg. Kretschmar is a no-nonsense woman who has strong opinions about Riefenstahl, who she says made films “against all of humanity.” She adds that “no one who lived in a big city can claim they didn’t know what was happening.” Riefenstahl’s response is to suggest a kind of helplessness. “Back then I couldn’t foresee what was going to happen, nor could millions of others. And you just have to believe that.” She adds, with increasingly animated gestures, “In retrospect, I’d be happy if I’d witnessed it like you. Because then I could say, ‘I witnessed it, I knew about it.’” She then claims a kind of shared victimhood. “But these days it’s much more difficult for those who didn’t know because no one believes them. And that is very difficult, believe me.”

What followed was equally disconcerting. The program provoked a strong response, with many letters and phone calls to Riefenstahl and the station supporting her, congratulating her, telling her the majority of West Germans were on her side. Veiel shows how Riefenstahl meticulously documented what she received: the response was divided into categories (which included “letters with flowers, telegrams or money” and “letters from National Socialists,” as well as “letters from those with different views, Communists, Jews, etc”). We hear several of the phone messages she received from members of the public. “Justice will prevail in the end,” a caller assures her. •