Although it often goes unremarked, a dramatic political revolution is underway. It is the ecological revolution: a phenomenon that escapes the attention of those who work at the scale of an electoral cycle. Even in the grip of a climate and biodiversity emergency, ecology is still neglected in cultural and political analyses, partly due to an entrenched science–humanities divide in education and public culture, and also because of a tendency to interpret environmental thinking as just “green politics.” But at a larger scale — the scale of a lifetime — we can clearly see there has been a generational change in ecological understandings of the Australian continent and the predicament of the planet.

It’s six decades since the publication of Donald Horne’s classic analysis of Australian politics and society, The Lucky Country (1964). Horne was blind, as were most others at the time, to the deep biological and cultural narrative of Australian earth, as well as to the enduring Aboriginal character of the continent. These insights have crystallised in our lifetimes and have transformed the way we understand the world and Australia’s place in it. This is not to criticise Horne for overlooking them; rather, it reminds us that if such a brilliant and edgy analyst didn’t see them, then these things were not part of the Australian zeitgeist of the early sixties, hardly even at the edges of it.

Fire, air and water were invoked in The Lucky Country, but they were configured as sun, freedom and the beach. The true power of the elements was yet to be appreciated. In mid–twentieth century Australia, the midday sun was bronzing rather than cancerous. “Open spaces” meant primary industry; “nature” often meant “raw materials.” And “the bush” was represented as a social setting, an inspiration for literary and artistic expression, and a subject of national myth-making.

Australian nature was the distinctive substance out of which a new society might be wrought, but it was not afforded independent agency and integrity, and nor was it regarded as finite. It was a setting, a commodity and a resource; it needed to be fought, tamed and reshaped to human needs. It was separate from humanity and subordinate to it. It was the background to the human drama.

There was one significant way in which Horne mobilised the environment politically, and that was in terms of geography. Australia’s geographical position on the globe was seen to have consequences. The southern continent’s proximity to Asia, its kinship with the Pacific, its long-distance triangulation with Britain and America: this was our unique geopolitical predicament.

What did it mean for emerging national, social and political identities? Another book published about the same time, a book whose title also entered the language — Geoffrey Blainey’s The Tyranny of Distance, published in 1966 — asked Australians the same question. Both books saw Australia in the 1960s as drifting geopolitically. Blainey ended The Tyranny of Distance with a vision of the island continent floating in the southern seas, unmoored. “The Antipodes,” he wrote, “were drifting, though where they were drifting no one knew.” For Horne too, Australia had “lost its bearings.”

But geography is often part of mainstream cultural and political debate so this was no great leap. Ecology, however, is very different — for it is a discipline that questions the centrality of humanity. It reminds us that humans are inescapably part of nature, and that their fate may even be determined by the elements and other creatures. Ecology first emerged as a scientific term in the 1860s and assumed professional status as a science in the 1930s, but it was not until the second half of the twentieth century that its insights gained moral and political impact.

The anthropogenic planetary peril that loomed in 1964 was atomic rather than climatic. The nuclear threat galvanised environmental thinking. American historian Don Worster in his book Nature’s Economy (1977) described the postwar period as “the Age of Ecology” and declared that it started in the New Mexican desert on 16 July 1945 with the detonation of the first atomic bomb. The atomic threat to all planetary life generated, he argued, “a new moral consciousness” founded on the insights of ecology: it was called “environmentalism.”

The book that signalled the arrival in the West of this new environmental political consciousness was Silent Spring, published in 1962, focusing on the dangers of pesticides, and written by the American marine scientist Rachel Carson. Almost contemporaneous with Donald Horne’s book, Silent Spring portrayed a very different natural world to his: one where technology was a threat rather than a promise, and where humans were conducting a giant, dangerous ecological experiment on Earth.

There were Australian stirrings of this new moral consciousness around the time that Horne’s The Lucky Country was published. In 1964 the Australian Conservation Foundation was formed; so also was the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland, of which Judith Wright was a founder. In 1966 the combative zoologist Jock Marshall published an Australian version of Silent Spring: it was an angry condemnation of Australian environmental practice called The Great Extermination: A Guide to Anglo-Australian Cupidity, Wickedness and Waste. In 1969, the first significant Australian conservation victory was won on the grounds of ecology and biodiversity when development plans in the Little Desert of Victoria were stopped by popular protest and a minister in the state government lost his seat. From the late 1960s, “the environment” announced itself as a ubiquitous term, an ecological concept and a political force.

The Moon missions of the Apollo space program fuelled a sense of the beautiful fragility of planet Earth, delivering some of the most reproduced pictures in the world. First there was “Earthrise,” taken on Christmas Eve 1968 as Apollo 8 went into lunar orbit. One of the three astronauts, Bill Anders, reflected: “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.” That revelatory image of the beautiful blue planet, visibly alive and floating alone, finite and vulnerable in deep space, had a profound impact on environmental politics and sensibilities.

Four years later, in 1972, a photo taken by the Apollo 17 mission and known as the “Blue Marble” showed the Earth as a luminous breathing garden in the dark void. Within a few years, the American scientists James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis put forward “the Gaia hypothesis”: that the Earth is a single, self-regulating organism.

In the postwar years there was an exponential shift in the impact of humans on the planet: the human enterprise exploded dramatically in population and energy use and rapidly began to outstrip its planetary support systems. World population, water use, tropical forest loss and species loss all soared after 1950. This turning point is known as the Great Acceleration and it charged the social excitement of the sixties. Now we live with the long afterburn of the fossil-fuel era.

Ecological thinking developed political momentum in Australia in the second half of the twentieth century and was expressed in public debates about pollution, population, wilderness, national parks, endangered species and sustainability. Conservation action was focused on enclosing and protecting threatened nature in place. Historian and activist William Lines wrote a book about environmental protest in postwar Australia called Patriots. Published in 2006, it was written under this twentieth-century paradigm of defending our natural heritage, as the subtitle declares. The phrase evoked the defence of heritage from development and the separation of nature from culture — in the book, the category of “natural” seems unproblematic and the use of “our” is unquestioned. “Heritage” here suggests something historic, a relic that might be preserved like an old building, object, or a fly in amber.

This was a time when getting back to 1788 was a purifying aspiration for conservation, another perceived boundary between nature and culture. This same paradigm of “defending our heritage” drove the noble quest to register “the national estate.” As if nature might be registered, fenced, signposted and preserved. This was the romantic age of state “national parks” and it was blooming when Horne wrote The Lucky Country.

Don’t get me wrong: I enthusiastically seek and defend conservation reserves; I love national parks and respond to the ecological integrity — and indeed historic landscapes — that they preserve. Expanding our national parks remains a vital quest. But now we live in a world where we recognise nature as fluid, dynamic, shifting and feral; it is part of us and not just optional and recreational; our survival depends upon it. Nature’s “management” (and that word is still used) changed its focus from national parks to public lands in general and then to private lands as well, all connected; and it now calls for corridors, baselines, renewal, respect and stories. Perceived wilderness has become beloved Country, nature is cultural and Indigenous care paramount.

Gradually in the 1980s and urgently from the 1990s, the spectre and then grim reality of the climate emergency brought a sense of extreme anxiety and even desperation to the quest for economic and social transition. By the beginning of this century we had a new metaphor for the extraordinary character of our times — the Anthropocene, the insight that we have entered a new geological epoch in the history of the Earth and have now left behind the Holocene, the relatively stable epoch since the last great ice age. The idea of the Anthropocene recognises the power of humans in changing the nature of the planet, its atmosphere, oceans, climate, biodiversity, even its rocks and stratigraphy. With the climate unleashed, the land of drought and flooding rains, of cyclone and firestorm, is now on steroids.

Just as nature could no longer be corralled, so did ecology invade the heart of economic debate. Pollution, extinction, forest destruction, population growth: these concerns were suddenly seen as symptoms of a much greater cataclysm. Local indeed became global; what you did in your backyard had planetary ramifications, for good or ill. The warriors at the frontline of logging protests were suddenly recognised not only as local heroes but also as defenders of precious carbon sinks, as fighters for the future of the Earth. Ecological thinking could no longer be dismissed as a dilettantish luxury; rather, it had become the single essential survival tool for our species.

Yet here we are, a quarter of the way into the twenty-first century, and still our politics and even many of our intellectual discussions fail to centre the existential emergency. We have come up hard against the limits of our human capacity to act rationally and collectively in the face of planetary peril. We have discovered that we are instinctive denialists when we contemplate extinction, even our own.

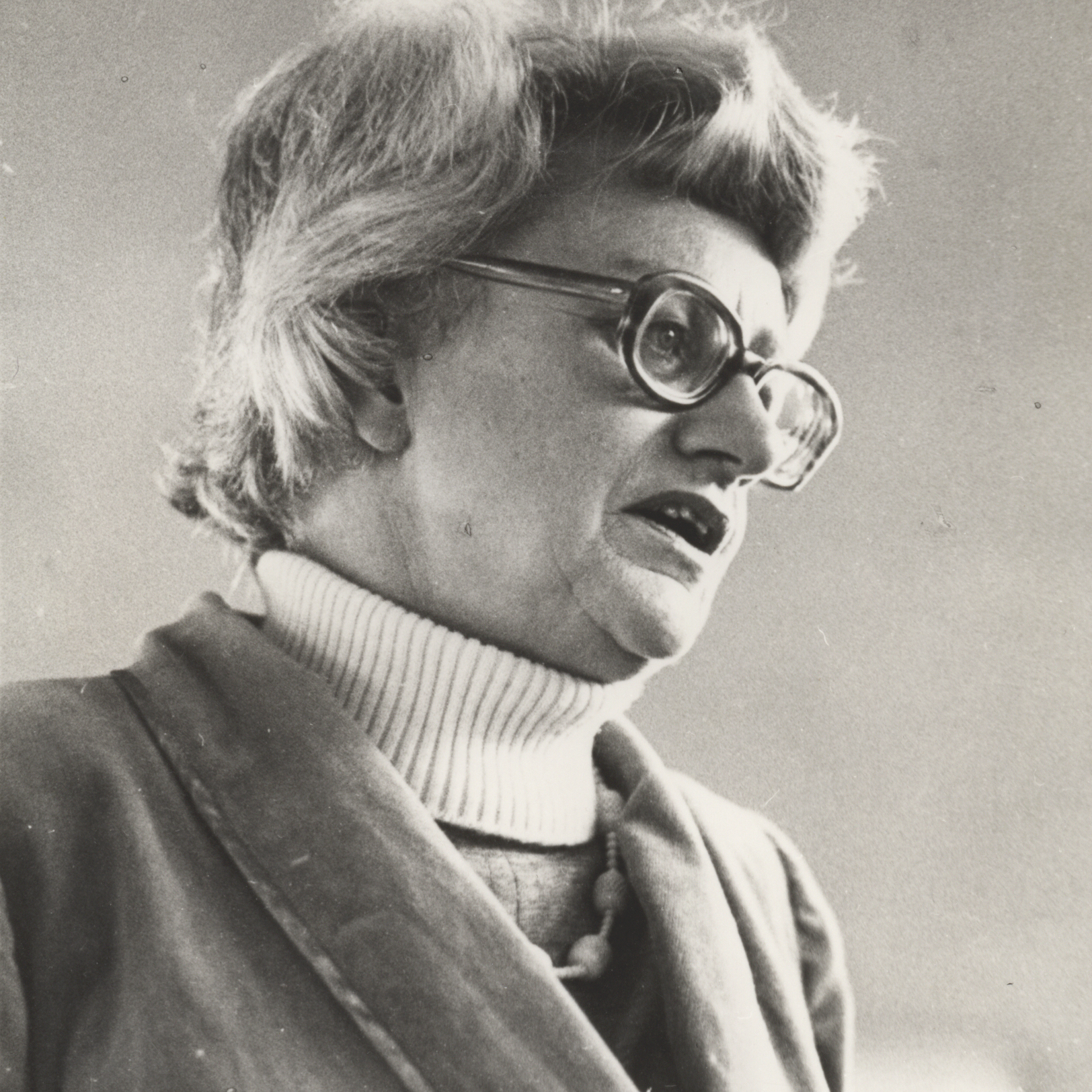

Two Australian biographies in the last half-century exemplify the ecological revolution. Judith Wright, born in 1915, became arguably Australia’s best known and most admired poet of the twentieth century. From the 1940s her poems quickly entered the national literary consciousness. Her early poetry was popular and critically acclaimed because of its distillation of white pioneer mythology, yet she was to become a critic of that inheritance, especially regarding the violent dispossession of Aboriginal peoples and the destruction of the environment.

Wright’s activism quickened in the 1960s through her work as president of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland, and soon she was passionately engaged in defence of the Great Barrier Reef from mining. Her advocacy moved swiftly from wildlife preservation to the conservation of whole ecosystems and Aboriginal rights.

Her defence of nature was founded on an ideological critique of Western civilisation; she always understood just how radical the ecological revolution was. It was not only about saving particular places; it was about saving the Earth. In the 1980s she said of the Great Barrier Reef: “It is not the explosion of the Crown of Thorns [starfish] population, but that of the human species and its wants, that will destroy the reef.” She foresaw that it would not be a local starfish but human planetary impact that would bleach the reef into oblivion.

The other biography I find instructive is that of Tim Flannery, born in 1956, who became a scientific celebrity in the years following Judith Wright’s death. He began in the late 1960s as a young field naturalist inspired by Jock Marshall, then as a zoologist volunteering and working for museums. He shaped his career by frontiering in New Guinea and the islands, became dedicated to understanding marsupials now and through time, and composed a grand, bestselling ecological narrative of Australian history called The Future Eaters (1994).

In the late 1990s, as the plight of the planet became obvious, Flannery turned urgently to climate change science and politics, which consumed him. In 2005 he published The Weather Makers, a year before Al Gore released his film, An Inconvenient Truth. The celebrated Australian became a global figure. The first act of the Abbott government in September 2013 was to sack Flannery as chief climate commissioner.

Tim Flannery was both product and exponent of the ecological revolution; he morphed mid-career from being the relatively uncontroversial student of new species in Australasia into the inescapably political role of global climate scientist. His first degree in literature and his warm regard for the humanities equipped him for versatility, storytelling and interdisciplinarity, the kind of creative synthesis demanded in the Anthropocene.

Judith Wright was a poet turned activist, Tim Flannery a scientist who can write; their philosophies were profoundly shaped by the ecological revolution. They came to think on a planetary scale, seeing Australia in deep time and deep space, keenly conscious of our responsibilities to a living, breathing, vulnerable Earth.

Donald Horne would recognise their investment in shaking the nation awake, their belief that good ideas might save us, but in the early 1960s he could not foresee how swiftly and brutally planetary fate would overwhelm Australia’s luck. •