Last month marked eighty years since the death of two earthshaking titans of the twentieth century, each of whom shared the grand illusion that he alone was capable of remaking the world. With Adolf Hitler’s suicide his “thousand-year Reich” fell a mere 988 years short of its target; Franklin Roosevelt lived only long enough to lay the foundations of a system that would survive not just one decade but eight.

Given that April 1945 was one of the most consequential months in modern history, now — as global governance faces its greatest test since the second world war — is an opportune occasion to review the stupidity and wisdom of the time that spawned the world we have all grown up in. Cue 1945: The Reckoning.

Eight years after the war, and a month before her coronation, Queen Elizabeth II was “pleased” to appoint a new representative to her loyal (and other) subjects in Australia. William Slim was an ideal appointment for those times when Churchill and Menzies were in their pomp.

The head of the “forgotten army” in the Burma campaign, Slim — whose illustrious military career had included service with the West India Regiment and not one but two Gurkha Rifles units — held the highest rank attainable in the profession of professional killers: field marshal.

Well before the British Commonwealth evolved into a multicultural forum of equally sovereign states under Elizabeth’s tutelage — before most of its members had even achieved statehood — it took a military form, with all its members wearing the uniform of the British Fourteenth Army, led by then Lieutenant General Slim.

Likewise India, two generations before it would become an economic superpower, was the workshop of that embryonic Commonwealth. Author Phil Craig spells it out literally and alliteratively: “The empire needed clothes, chemicals and cement, parachutes and paint, machine guns, mortars and medicines, and by 1945 India was producing as much of all this as South Africa, New Zealand and Australia combined.”

While India, and those of her most active military leaders who aligned themselves with one or another of the Great Powers, are the main actors in this unflagging drama, Craig’s vision is as global as was the war they had joined. His kaleidoscopic approach combines viewpoints from various theatres of war: for a few pages we are immersed in Burma, then we are teleported to Borneo, Singapore and, as the conflict spreads, Tokyo, London, Yalta and Formosa.

But the roving eye is always drawn back to India, the inspired setting for Craig’s account of the clash between the globe’s mightiest nations from the viewpoint of the colonised. We see with clarity how the pawns in their Great Game of geopolitical chess become the agents of a postcolonial, postwar future as nations in their own right.

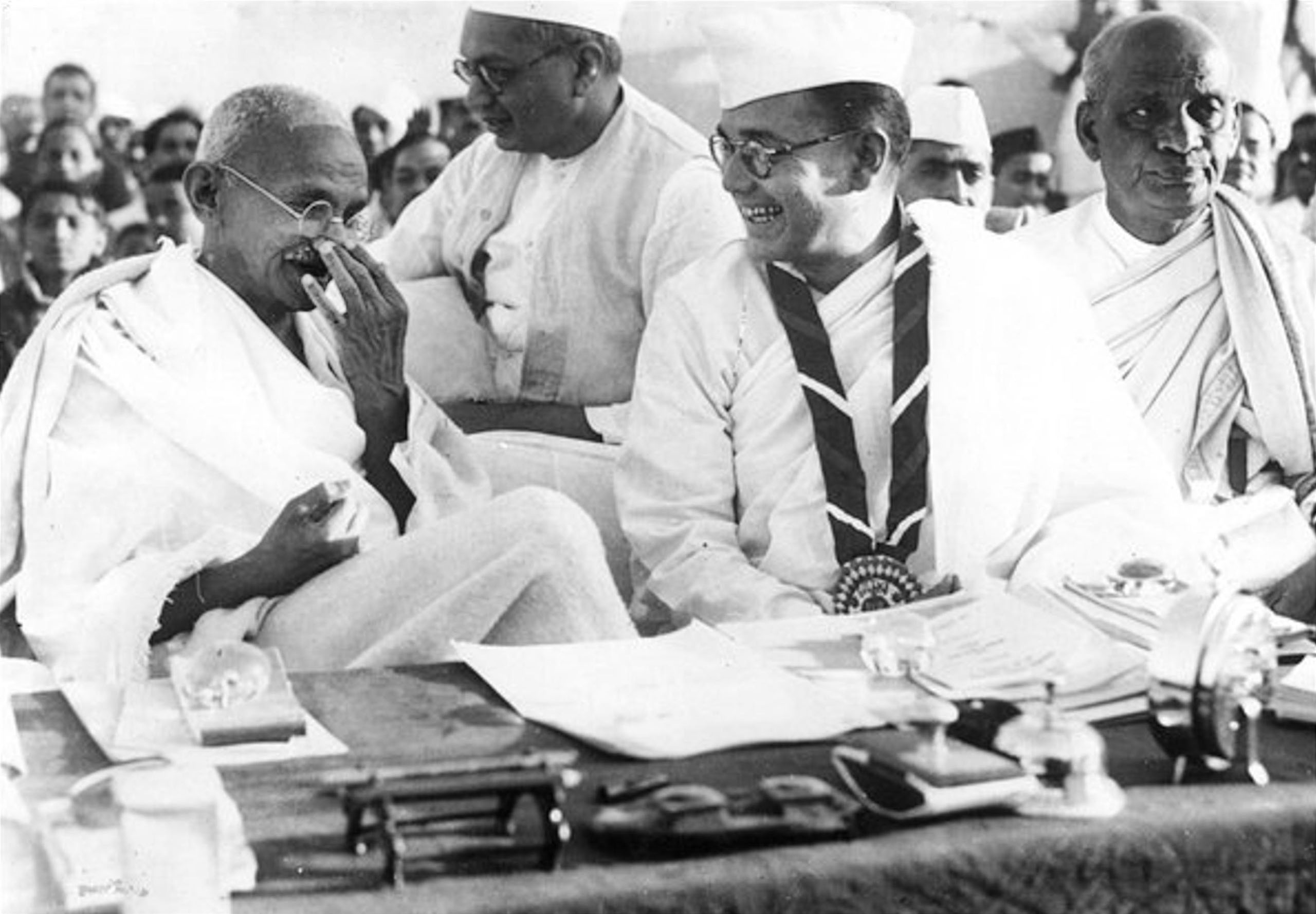

Gandhi’s lifelong pursuit of non-violence grabbed the world’s imagination, but on the subcontinent itself, as Craig points out, Subhas Chandra Bose, a fellow nationalist who took the path of armed engagement, remains equally famous eighty years later.

Bose, aka the warrior-prophet Netaji (“most respected leader”) to Gandhi’s Mahatma (“Great Spirit”), is commonly regarded at home and throughout the diaspora as a “freedom fighter” in contrast to Gandhi’s image of deep spirituality. British novelist Gerald Seymour has been credited with coining the phrase “One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist,” and Craig shows how that principle works in the real world.

Bose, who like Gandhi had studied at Cambridge, took the path of active rather than passive resistance. The British, perceiving both men as endangering colonial rule, placed them under house arrest early in the war. Whereas Gandhi had appealed to Englanders’ declared attachment to “fair play,” Bose regarded John Bull as the immovable enemy of his people.

Both lived up to their images: passively resistant Gandhi wasted away, protesting injustice via hunger strikes; actively resistant Bose hastened away, escaping from his house in Calcutta before trekking 2300 kilometres to Kabul and seeking out the German Ambassador, who arranged his flight to Berlin.

To adapt an Arab truism, he took the enemy of his enemy for his friend. A false friend, as it turned out. In May 1942 “Bose met Adolf Hitler for the first and only time.” Hitler advised him that the situation wasn’t timely for an uprising in India because “German forces were not in a position to support it.”

As the kaleidoscope slowly turns, allowing the reader to concentrate on one facet at a time, Craig synthesises the lessons to be drawn from each theatre of war and each episode recounted.

Grand themes whose significance would extend far into the postwar future are identified and discussed. Perceptions of racial arrogance, of course, proved incendiary fuel for the anti-colonialists; but Craig also explains how the swift end of 350 years of English governance just two years after the war owed much to the ambivalence of the English themselves, and of their political parties, faced with the cost of maintaining an empire. The greatest gift that Craig, a British journalist whose famous television platforms included World in Action and Panorama, brings to this volume is the ability to see the view from opposing sides of the imperial divide.

At one point he notes, “Many British people are so in love with the ‘underdog’ version of the Second World War — Dunkirk, rationing, the Blitz and ‘the Few’ — that they fail to understand that much of the planet never once looked at their country in that way, and for good reason. Britain was more often seen as the over-dog…”

He sees that Japan’s rapid conquest of Southeast Asia proved how “Asian societies no longer needed outside or control to run a sophisticated state, build a modern military or create a world-class economy.” But his clear-sightedness is not one-eyed: never once does he understate the acute pitch of brutality inflicted by Japanese soldiers on prisoners of war from Changi to Sandakan.

Nor does he let the reader pretend that, when it comes to the capacity for evil, all the light in that most Manichean of conflicts was on one side while its foes were steeped in moral darkness. If racism today is classified as a question of acceptable and unacceptable speech, infinitely more eloquent is the test of actions.

The Bengal Famine of 1943 — one of the century’s great disasters yet overshadowed by the global power struggle — killed three million people (equivalent to nearly half the Australian population at that time). “However hard the authorities tried to help,” Craig observes, “and try many of them did, they would surely, inevitably, have done more had the food run short in Surrey, Manitoba, the Western Cape, New South Wales or North Island.” You can’t argue with that.

Marring this overwhelmingly absorbing read is a smattering of errors, the blame for which belongs in part to Craig’s editors. Most persistent is the misnaming of soldiers from the Malay Peninsula as Malaysians rather than Malayans: the Federation of Malaysia didn’t come into being until 1963.

Dehra Dun, India’s military and educational hub, appears as Deera Dun; and one of the lesser-known characters Craig introduces, English wartime nurse Angela Noblet, stationed on the Lopchu Tea Estate in Assam, simply could not have had “views of the magnificent, unconquered Everest in the distance.” Everest is more than 250 kilometres away; the peak you can see from there is the world’s third loftiest, Kanchenjunga, seventy kilometres due north.

More amusing, though failing to elicit the emotional response the author must have intended with the graphic term “pus-filled boots,” was how it turned up on the printed page as “puss-filled boots.”

Even if Craig’s book doesn’t dwell on the duality of his vision, it is baked into the text on nearly every page. West/East; democratic powers/autocracies; passive/active resisters. But even within the force field of active resisters there were two diodes, as it were: Bose, head of the Indian National Army, “the largest all-volunteer military force in history.” Opposing him, Kodandera Subayya “Timmy” Thimayya, who led the forces under the command of Lord Louis Mountbatten, supreme commander of allied forces in Southeast Asia. Tellingly, when Timmy met Louis (yes, I know), it was at the British naval supremo’s invitation.

Apart from Craig’s ability to trace historical patterns by threading individual stories into a coherent and satisfying narrative, he brings one other great gift to his task, a gift honed in his TV incarnation — a highly developed visual sensibility. It is easy to imagine this book being turned into a box-office triumph.

Post-independence, “Timmy” became commander of the entire Indian Army, “the pinnacle of his life’s work.” As a parting gift to curious readers, the closing pages reveal the personal connection that explains why Craig was prompted to tell this epic story, with all its subplots. But no spoilers here… buy the book! •

1945: The Reckoning — War, Empire and the Struggle for a New World

By Phil Craig | Hodder & Stoughton | $34.99 | 380 pages