Though the Liberal Party’s “women problem” might seem perennial, the conservative side of Australian politics could once boast of being at the vanguard of female parliamentary representation — with the important caveat that Australia was never as advanced on this issue as we were with our early granting of female suffrage.

Eight of the first ten women elected to federal parliament were Liberal Party members, with one of the remainder being the Independent Labor MP for the Victorian seat of Bourke, Doris Blackburn. Likewise, almost every woman to achieve the honour of being the first elected to each of our nation’s state parliaments sat on the centre-right of the political divide. The sole exception was a Tasmanian, Margaret McIntyre, who was elected to the Legislative Council in May 1948 as a true independent, only to be tragically killed in a plane crash less than four months later.

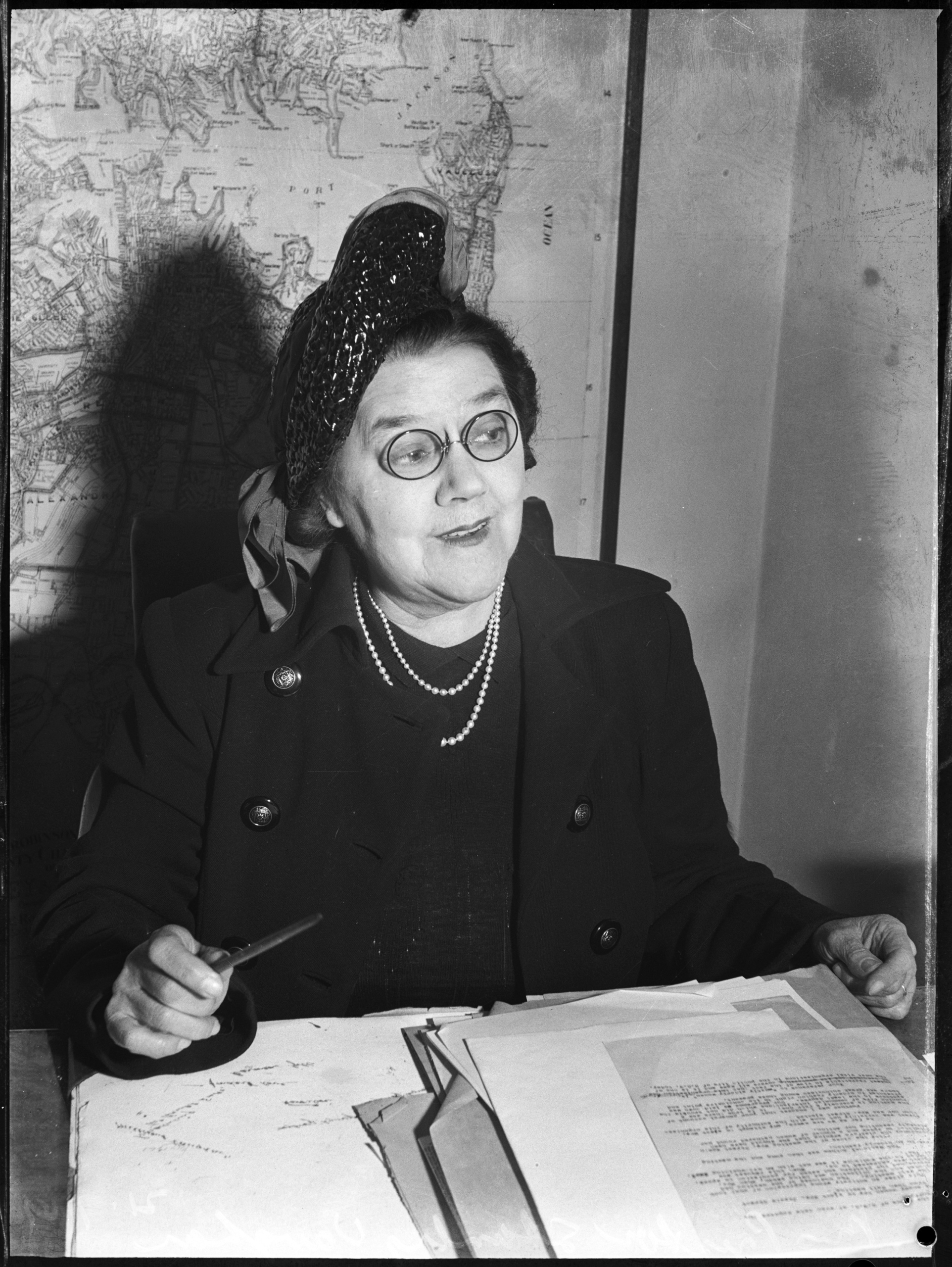

But, as Wendy Michaels shows in A Battle-Axe in the Bear Pit, her new biography of the NSW record-holder Millicent Preston Stanley, these conservative trailblazers hardly received the consistent support of their male colleagues. That support was even less forthcoming and reliable a century ago — when “Miss” Preston Stanley became one of the members for the multiseat Eastern Suburbs electorate in 1925 — than it is today.

A full-length biography of Millicent, as the author refers to her subject throughout, is long overdue. Not only did she crash through the gender barrier in our oldest parliament and most populous state; as founder of the Australian Women’s Movement Against Socialisation, or AWMAS, she also led a national campaign that may well have tipped the scales towards Robert Menzies at the watershed federal election of 1949 — and thus altered the course of Australian political history. That Millicent did so by deliberately keeping her organisation separate from the newly formed Liberal Party tells you all you need to know about her experience of dealing with patriarchal party machines.

Standalone conservative women’s organisations have a storied history across Australia. Often predating or outliving their male counterparts, groups like the Australian Women’s National League in Victoria and the Women’s Liberal League in New South Wales played an essential role in the broader story of Australian liberalism. It was in the latter that Millicent would receive her initial political mentorship from prominent Swedish-born suffragette Hilma Molyneux Parkes, after whom Hilma’s Network, an organisation designed to lobby for increased women’s representation in the Liberal Party, has recently been named.

But despite the depth of this history and all that has been written about it, Michaels doesn’t establish exactly why Millicent was attracted to the Liberal side of politics, beyond the fact that her single mother somehow managed to move her family “from their various domiciles in the working-class suburbs of Surry Hills and Redfern to a flat in the middle class suburb of Darling Point.” That aspirational journey might be interpreted as an example of the social mobility on which contemporary Liberal leaders like Joseph Cook pinned much of their ideology.

Michaels implies that Millicent’s anti-socialism came from being around the Women’s Liberal League. But it didn’t inspire her to join that organisation, and throughout the book Michaels is clearly more comfortable talking about her subject as a feminist pioneer than as a Liberal partisan by conviction. Indeed, Millicent oversaw a split in the Feminist Club whereby the more progressive members left and formed their own organisation. She even had a physical altercation with radical feminist “Red Jessie” Street when the latter gatecrashed an AWMAS rally.

Michaels’s less-than-full understanding of her subject’s political perspective reaches a climax at the end, when she suggests that Millicent would have applauded Julia Gillard’s famous misogyny speech, ignoring the fact that it came in response to criticism of her government’s appointment to the parliamentary speakership of Peter Slipper, who was revealed to have sent misogynist messages, and was therefore interpreted by many conservative women as compromising the very principles it was supposed to be championing.

But any failure to appreciate Millicent’s broader political philosophy is more than made up for by the fact that her story as feminist pioneer is a remarkable and fascinating one. Despite Millicent’s limited personal papers, Michaels has succeeded in reconstructing that story by drawing heavily on the National Library’s Trove newspaper database.

Most important is Michaels’s reconstruction of Millicent’s childhood backstory, which she appears to have deliberately obscured. Millicent’s father was an abusive drunkard who ultimately abandoned the family, chased an unearned fortune in the West Australian goldfields and met an ignoble end. But Millicent never revealed the arduous divorce proceedings her mother went through, instead insisting that her father had simply died. The divorce did have the unexpected bonus of leaving her with the double-barrelled surname that gave her an aristocratic air valuable in some conservative circles.

This early experience shaped Millicent’s choices and political career. She notably eschewed marriage until she was well beyond childbearing age, a fact her opponents attempted to use against her by claiming she couldn’t accurately speak of a typical woman’s experiences. She nevertheless became a fierce advocate of investments in maternal and child health, inspired perhaps by the loss of an infant sibling who had died of dehydration after two weeks of diarrhoea and vomiting.

Her father’s behaviour also inspired her fervent belief in the temperance cause, an issue that led many women to her side of politics at the turn of the twentieth century. She was a vocal proponent of the early closing referendum of 1916, which created the infamous six o’clock swill, and her decision to join the Women’s Liberal League notably coincided with NSW Liberal leader Joseph Carruthers’s endorsement of “local option” prohibition polls in each electorate. (Carruthers later admitted that the scheme only ended up restricting the liquor trade in suburbs where it had scarcely been an issue in the first place.)

As Michaels documents, Millicent even had an unfortunate flirtation with eugenics at around the time this still-mainstream idea was advertised at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition that she attended in San Francisco in 1915. Her hope was that it might alleviate some of the human misery associated with what many women endured in domestic life.

But arguably the most important manner in which a broken home inspired Millicent to take action was over child custody. This was a time when NSW law still upheld the “father right” principle, under which a man could only be denied custody of children if he had demonstrably rendered himself unfit for “paternal control.” As with modern debates over whether courts have gone too far the other way in preferencing mothers, this issue evoked the deepest of political passions.

The passion was especially evident after a NSW court granted custody of the daughter of English actress Emélie Ellis to her clearly inadequate husband, partly on the assumption that Ellis’s career was not conducive to the commitment required for motherhood. Millicent used this case as the casus belli in her fourteen-year crusade to have the law changed, first through petition, then in parliament, and finally in highlighting the case’s absurdity in a melodramatic play whose opening-night audience included the governor, the prime minister and premier.

Michaels’s description of Millicent’s repeated efforts to have private member’s bills debated to rectify this and other issues is a highlight of A Battle-Axe in the Bear Pit. As readers, we witness her anguish as she must turn down a Labor minister who tried to bribe her with a promise that he would take action in exchange for her vote when Jack Lang’s Labor government held an extremely slim parliamentary majority. Michaels conveys Millicent’s ever-building frustration as she makes attempt after failed attempt to bring about change.

Although Michaels lacked evidence of Millicent’s inner thoughts, Trove allows her to quote myriad other opinions of her subject and her campaigns. In fact, the sheer quantity of views might be taken as a meta-commentary on how female politicians are often bombarded with greater scrutiny than their male counterparts.

Ironically, it was by writing, directing and starring in Whose Child?, and thereby embracing the attention and superficial judgements, that Millicent was ultimately able to win the legislative change that her parliamentary efforts could not. Although justice minister Lewis Martin’s “spontaneous” change of heart while watching the play was clearly stage managed, the publicity given to the show is sure to have been a telling factor weighing on his mind.

Similarly with the mass rallies of the AWMAS and her regular women’s section for the Daily Telegraph, it was often outside the Legislative Assembly that Millicent was able to make her greatest impact. She only served one term; and while the Nationalists did preselect her for the new single-member seat of Bondi, they not only allowed an Independent Nationalist candidate to defeat her but also rewarded him with admission to the party room. Her later attempts to win preselection for the Senate were unsuccessful.

But for all the indifferent colleagues and the general isolation (she was given an office in a parliamentary annex away from where the vast majority of MPs went about their business) there were exceptions that made Millicent’s endeavour more endurable. These included long-time supporter and former prime minister Billy Hughes, campaign manager Reginald Weaver (who would go on to become the first leader of the modern NSW Liberal Party) and of course the women whose cause Millicent felt she was championing.

At a time when the payment of members was a relatively new, involvement in politics was still thought of as an act of public service. For Millicent, it was a true vocation that consumed a lifetime, bringing with it many joys and privileges, but also sorrows and exasperations. We are lucky to have this new record of some of the personal sacrifices that were required to bring us to our present state of relative equality and opportunity, and some indication of the sacrifices that will be required to more adequately achieve the ideals — both liberal and feminist — for which people like Millicent strived. •

A Battle-Axe in the Bear Pit: Millicent Preston Stanley MP

By Wendy Michaels | Connor Court | $29.99 | 250 pages