Daniel Kehlmann’s The Director, translated from the German by Ross Benjamin, is a deft, dark, densely packed tale of compromise and capitulation.

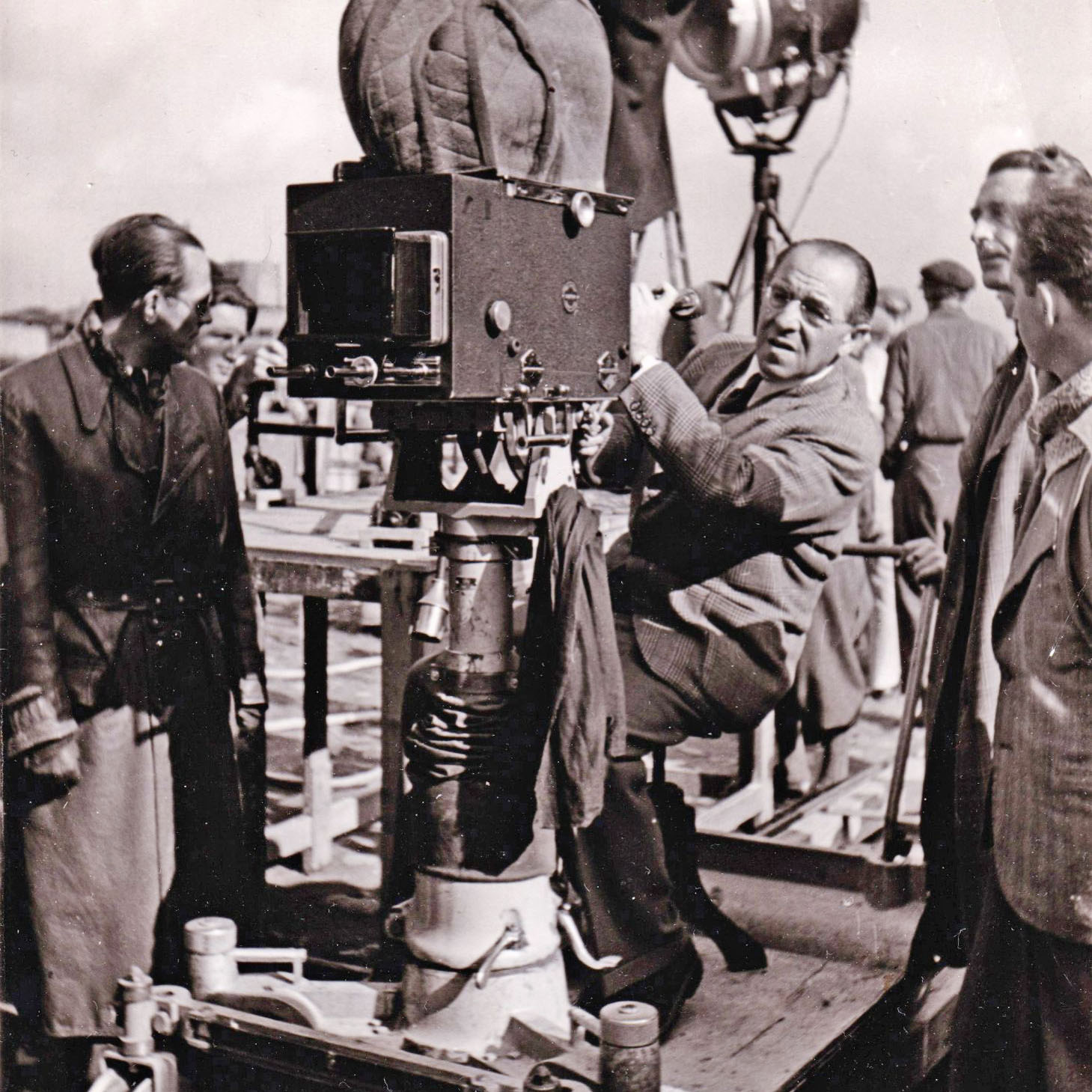

Kehlmann depicts choices made in the grimmest of circumstances, sometimes in the name of art. His central figure is G.W. (Georg Wilhelm) Pabst, the Austrian-born filmmaker probably best known for Pandora’s Box, the remarkable 1929 silent movie starring Louise Brooks as a wilful object of desire who brings chaos and destruction in her wake.

Pabst was an innovator and artist with a particular gift for working with actors. Kehlmann’s focus is a disconcerting trajectory in the life of a filmmaker — once known as “Red Pabst” because of his approach to social issues — who left Germany because of Hitler’s rise. Yet he returned just before the outbreak of war and ended up making films funded by the Reich. What happened?

When Kehlmann introduces Pabst he is adrift in 1930s Hollywood, hampered by his limited grasp of English. He is overlooked or patronised, constantly confused with other German directors and their films, congratulated on having made Lang’s Metropolis or Murnau’s Nosferatu. His only job in the United States had been directing a circus drama, A Modern Hero (1934), and it was a miserable experience. He had no real control over the creative process, and the film was a critical and commercial failure.

Kehlmann allows himself a few liberties. In a note at the end of the book he says that “although this novel is largely inspired by the life stories of the historical G.W. Pabst and his family, it is a work of fiction.” He notes that he invented the character of Pabst’s adolescent son, Jakob (although Pabst had two sons, born in 1924 and 1941).

Pabst returned to Austria in 1939 ostensibly for family reasons. Then, unable to leave, he tried initially to resist suggestions that he put his talents to work for the state. Kehlmann depicts a gradual process of accommodation, an accumulation of quotidian compromises. At first, there is a degree of awkward self-awareness in Pabst’s perception of what is happening around him. “Three times he saw parades: drums and brown uniforms and sharp marching in lockstep. Passersby stopped and raised their right hand, and Pabst, not wanting to attract attention, hesitantly did the same — just for a second, with a jerk of his shoulder, after which he felt soiled to the core.”

He is hardly alone. With bleak clarity, The Director shows how every part of society is implicated in one way or another. Sometimes there is enthusiastic cooperation: the caretaker at Pabst’s family home in Austria is an early convert to Nazi values; the adolescent Jakob is enrolled in a high school that eagerly embraces every aspect of Nazi ideology.

In a chapter called “German Literature” Pabst’s hapless wife, Trude, joins a reading group, hoping for some social contact. Its members, mostly wives of influential men, turn out to be cheerleaders for a Reich-approved author called Alfred Karrasch, and they have a ruthless attitude towards dissent or difference. Trude, who has a better grasp than her husband of their situation, soon realises that she must conceal her true opinion of the author’s latest (to her mind insipid) work. A woman is abruptly booted from the group because she can’t help mentioning incidents and people the others would prefer to forget.

The narrative of The Director is mostly in the third person. It is framed, however, by two first-person sequences that take place much later. A befuddled elderly man is transported from a sanatorium for a television interview about working with filmmakers like Pabst. His denial of the existence of a particular work sets the scene, intriguingly, for much of what it is to come. It becomes apparent in the final chapter that he holds the key to a central mystery of the film, even if he is unable or doesn’t wish to remember it.

Another first-person sequence is narrated by an unnamed figure who can only be the author P.G. Wodehouse. Once again, Kehlmann imaginatively engages with real events. Wodehouse, creator of Jeeves and Bertie Wooster, was living in France when Germany invaded in 1940. He was moved from one internment camp to another, then put up in a five-star hotel and asked to do radio broadcasts about his time in the Reich. He agreed, seemingly oblivious to the implications of his actions. It is through his eyes that we see the premiere of the second feature Pabst makes under the aegis of the state.

Wodehouse is one of many secondary characters or supporting cast-members effortlessly and entertainingly woven or projected into the narrative. Often they are real-life figures, sometimes they are imaginative creations. Among them are Louise Brooks and Greta Garbo: although Pabst played a vital part in their careers, both reject him in their different, distinctive ways when he appeals for their help.

An unnamed Goebbels makes an unnervingly over-the-top appearance to threaten and flatter the filmmaker, and Leni Riefenstahl turns up on a couple of occasions. Pabst had already worked with Riefenstahl as an actress on a silent film he co-directed; by the time they meet again, she has made Triumph of the Will and established her credentials with the Reich. She prevails on Pabst to assist her with her first fiction feature, Lowlands, a work she directs and stars in. It is an unsettling experience for him, but it also foreshadows a decision he makes about a film of his own.

Kehlmann brings to his subject particular insights from his own experience. His father, a director of film and television, was a school student during the second world war and spent several months in a labour camp. His mother was an actor. And recently Kehlmann himself has been a screenwriter for film and television. He is able to create convincing, entertaining accounts of the filmmaking process; he can also imbue certain passages with cinematic qualities and reference points.

The most sustained imaginative engagement in The Director concerns the making of a film called The Molander Case, based on a novel by Karrasch, the author espoused by Trude’s reading group. It is a genuine Pabst work, shot in Prague in 1945, under chaotic circumstances and now regarded as missing. Its production and fate lend themselves to speculation, and Kehlmann does a great deal with this. The movie becomes, in his account, a distillation of all the absurdities, compromises and haunting questions around Pabst and his activities at a time when he was seemingly given the creative control Hollywood would not allow him. The director thinks he can work against the grain, perhaps even create a masterpiece.

Kehlmann has already shown us Pabst’s habit of viewing the world as if setting up a shot, or imagining life in cinematic terms as an unfolding of scenes he can direct. With The Molander Case, it is as if Pabst believes that his creative powers can transcend not only the banality of the source material but also the circumstances of its creation.

The production marks Pabst’s most grim capitulation, but its fate is also the stuff of comedy and irony, with a succession of twists and turns. In its exploration of self-deception, complicity and surrender, The Director is a heady mixture of the compassionate and the unsparing, the tightly organised and the expansively imagined. •

The Director

By Daniel Kehlmann | Translated by Ross Benjamin | Quercus | $34.99 | 333 pages