During August 1945, in the last days of the second world war, US bombers flew from the Micronesian island of Tinian to drop atomic weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Now, on the eightieth anniversary of the bombings, the United States is again readying Tinian for war.

Indigenous Chamorro in the Marianas Islands have bitter family memories of the wartime fight between Japan and the United States to control their islands. The clash of imperial powers in the 1940s has echoes today in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, or CNMI — of which Tinian is one of three principal islands — at a time of strategic competition between the United States and the People’s Republic of China.

Tinian’s crucial role is often ignored in commemorations of the atomic bombings in 1945. Fighting their way across the Pacific, US marines defeated Japanese forces on the island in July 1944. They soon transformed the island into an airbase for striking targets in Japan, 2400 kilometres away. The refurbished North Field airstrip was the largest in the world at the time, with four 8500-foot runways and facilities to support more than 40,000 personnel.

The island served as the key base for the incendiary bombing of Japanese cities by the 313th Bombardment Wing, including the firebombing of Tokyo on 9 March 1945. An estimated 100,000 people died in that one attack, after more than 300 US aircraft bombed civilian housing. In Operation Starvation, the same force mined Japanese shipping lanes to reduce civilian access to already limited food supplies.

Months before atomic bombs were ready for use, the US high command proposed using airbases on Guam for a nuclear attack on Japanese cities. But an air force memo to the Manhattan Project in late February 1945 advised it now saw Tinian as “the most desirable island to base the 509th Composite Group.” In July, following the first successful detonation of an atomic device, known as the Trinity test, the US military prepared an arsenal of nuclear weapons to attack Japan. The initial target list included Kyoto, Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki.

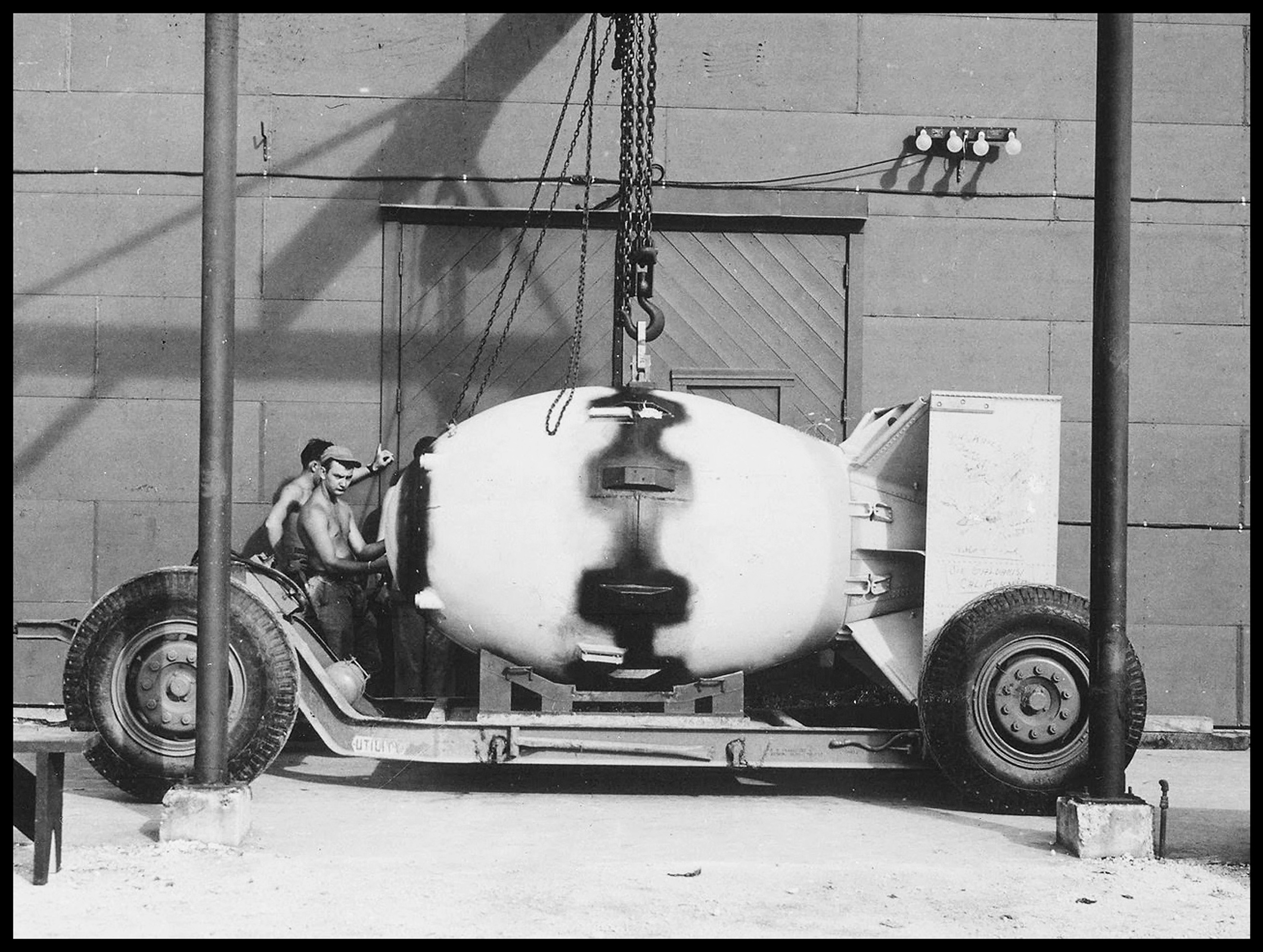

In the early hours of 6 August 1945, a B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, took off from Tinian for Hiroshima. At 8.15am, Captain Paul Tibbets ordered the release of an atomic bomb, codenamed “Little Boy,” over the Japanese city. The city of Kokura was scheduled for the next attack, but when bad weather intervened on 9 August the Bockscar flew instead from Tinian to Nagasaki, which was destroyed by the “Fat Man” bomb.

Most of the people killed in these two attacks were civilian non-combatants. By year’s end, an estimated 140,000 people had died in Hiroshima and 74,000 in Nagasaki. An estimated 38,000 of the dead were children.

A month after the attacks, General Leslie Groves, the head of America’s Manhattan project, misled Congress by declaring there was “no radioactive residue” in the two devastated cities. Contradicting evidence gathered in Japan by his own staff, Groves said that people exposed to radiation from the atomic blasts would not face “undue suffering. In fact, they say it is a very pleasant way to die.”

In reality, many nuclear survivors, known as hibakusha, lived on for decades, stricken by cancer, leukemia and other diseases caused by exposure to ionising radiation.

After the war, the United States administered these and surrounding islands in the northern Pacific as the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, the only strategic trusteeship created by the United Nations. Micronesia was still recovering from the wartime damage from US Marines fighting their way across scattered atolls and the US forces bombarding Japanese installations, with islanders trapped between the two imperial powers.

In 1946, soon after the Japanese surrender, the US military began to test nuclear weapons, with sixty-seven atomic and hydrogen bomb tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958. Following Britain’s hydrogen bomb tests on Christmas (Kiritimati) Island in the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony, the United States conducted another twenty-four nuclear tests on the island in 1962, using the old British airstrip and military base.

Eighty years after planes from flew Tinian to bomb Japan, the United States still administers some of these Micronesian islands as a colonial power. In the south of the Marianas archipelago, the US Indo-Pacific Command controls more than a quarter of Guahan (Guam). The US territory hosts key American military bases, including Apra Harbour Naval Station, Andersen Air Force Base and Camp Blaz, a new US Marine Corps base. Further north in the archipelago are Tinian, Saipan and Rota, the three largest of thirteen islands in the CNMI, an unincorporated territory of the United States created in 1975.

These bases are central to US plans to contain China in the western Pacific. Because Guam is within range of North Korean and Chinese missiles, the Obama, Biden and Trump administrations have spent billions of dollars upgrading airfields and dispersing fuel and ammunition supplies to neighbouring Micronesian nations.

Washington’s ambitions in the region aren’t going unopposed. Among the groups challenging the dominant narrative of the Micronesian islands as “the tip of the spear” for the US military in the western Pacific is Our Commonwealth 670.

“Our group is linking what we see as increased militarisation in CNMI to the ongoing militarisation of Guam, the desecration of indigenous lands and denial of indigenous rights,” Saipan-born educator and activist Theresa “Isa” Arriola, a member of Our Commonwealth and a leading voice questioning the military build-up in the islands.

“We formed because we wanted to educate the community and bring awareness to the narratives that so often surround the islands — that we are strategic locations. There’s a kind of geographic determinism that follows that logic, which says ‘you must be used for war in this broader war machine.’ So we want to push back on that, and link militarisation with demilitarisation, indigenous sovereignty and indigenous rights.”

For Chamorro people, the growing militarisation of Tinian reopens mental and physical scars. “The presence of World War Two is still very much a part of our community’s collective consciousness,” says Arriola. “Our grandparents talk about their experiences with the war. We also see it in the physical landscape: there’s unexploded ordnance still left on Tinian from World War Two. When they’re refurbishing the runway or other military projects, they find that old ordnance.”

As a child, Arriola found scraps of bombs on the beaches of Saipan. Today, unexploded ordnance, or UXO, remains a hazard in most wartime battlegrounds across the Pacific Islands. People are still being killed or maimed when they disturb ageing US and Japanese bombs, grenades and ammunition in Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Kiribati, Palau, Federated States of Micronesia and CNMI.

On Tinian, a US navy team disposes of UXO on land leased by the US Defence Department. But UXO outside these military leases is the responsibility of the local CNMI government. It must seek grants from the US Environment Protection Agency Brownfields program or finance under the US Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, which provides grants for disposal of hazardous materials. These programs have been gutted as the Trump administration reduces funding to the EPA and other environmental agencies.

Under a program known as Agile Combat Employment, the US government has begun to refurbish second world war airbases in CNMI, the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau. In April last year, the US Air Force announced a US$409 million contract for Texan construction firm Fluor to refurbish and extend the old North Field airfield on Tinian. The Guam-based construction company Black Micro was also awarded a US$220 million contract to extend a cargo pad, taxiway extension, fuel tanks, roads and maintenance facilities on the island.

The US Defence Department has recently released environmental impact statements seeking public comment on further military expansion in Tinian, which would include live-fire ranges, a base camp, communications infrastructure and a biosecurity facility.

It’s a decade since the US military announced plans to use the CNMI island of Pagan for weapons testing, causing uproar in the community. In 2015, a draft EIS received more than 30,000 public comments in opposition. In response, the US defence department halted proposed military activity on Pagan and withdrew proposals for artillery, rocket and mortar exercises on Tinian.

The Pagan campaign linked community elders with younger activists, says Theresa Arriola, who are now opposing renewed plans for a military build-up on Saipan and Tinian. As the US military releases new EIS for public comment, community groups like Our Commonwealth, Marianas for Palestine and Prutehi Guahan are mounting community education programs but also demonstrating again militarisation of the islands.

“Right now on Tinian, they’re reconstructing the same runway they used in 1945 and there is the concurrent release of two major environmental impact statements,” Arriola says. “One is the CNMI Joint Military Training EIS, that outlines a lot of major changes on the island of Tinian, including live-fire training, public access restrictions and other hazards.”

In June, activists interrupted a public meeting on the proposed military training expansion in Tinian, chanting “No build-up!,” “No war!” and “Free, free, Palestine!” Chamorro activist Anufat Pangelinan told the Marianas Press: “We don’t want to be part of a war we don’t support. The Marianas shouldn’t be a tip of the spear — we should be a bridge for peace.”

Community groups questioned military plans to build a fuel pipeline over Tinian’s aquifer, the only potable source of water on the island. They raised potential hazards to fishing boats travelling between Saipan and Tinian during live-fire exercises. US Marine Corps Forces Pacific executive director Mark Hashimoto acknowledged that “the top five concerns that the community still has include water resources, solid waste, noise, the impact on police, fire, and medical capabilities, and also access to the military lease area.”

For Arriola, the EIS process doesn’t provide sufficient evidence for decision-makers, and downplays concerns over indigenous land and culture. “That’s what everybody is talking about — the land, and the health of the land for future generations and the ability to maintain indigenous sovereignty,” she says.

“Our community is suffering,” Arriola adds, “but most people aren’t reading through these extremely tedious, very cumbersome Environmental Impact Statements. It’s really complicated, and an undue burden that’s consistently placed on us, especially when multiple EIS are released. They don’t address a lot of our questions, they don’t have proper baseline data, they don’t have proper mitigation plans in place. We have a long history of seeing the skirting of environmental regulation or not properly implementing the EPA process.”

The challenge for community activists is the strong military culture across Guam and CNMI, and a long tradition of Micronesians joining the US armed forces to obtain training and economic opportunity.

The significant US presence means communities are economically linked to the military, says Arriola. “So it’s hard to say ‘I’m an activist and I disagree with someone joining the military.’ There are so many people amongst our friends and our family that are already in the military. It’s so much a part of the fabric of our everyday lives. So it’s not about faulting people for joining the military, but it is about critiquing the military-industrial complex that is keeping us so closely tied to the military as a form of survival.”

The upgrading of the wartime airstrip and other military plans for Tinian are often presented as a bonanza for local businesses. With hundreds of US contractors already on the island, cafe owner Marie Rose Bunao told local media that “business is mostly driven by department of defence projects. The military money goes into the community. Whatever they spend stays here.”

These resources can help replace reduced tourism since the Covid pandemic, amid scandals surrounding the collapse of a hotel and casino operation in Saipan. (An exclusive gambling license was issued in 2014 to Hong Kong–based Imperial Pacific International, which was soon embroiled in disputes over corruption, delayed construction and abuse of workers’ rights.)

Although the CNMI government is still owed US$160 million in back taxes from the casino fiasco, supporters of US military construction predict a new bonanza of investment. Tinian mayor Edwin Aldan says the current military expansion could bring over a billion dollars in investment over the next fifteen to twenty years.

“We are in a very tight economic situation right now,” Arriola acknowledges. “Civilian and military infrastructure are becoming so interlinked that you can’t uncouple them. But around the dinner table, you’re not talking about geopolitics,” she stressed. “You’re asking: Will we be disrupted by the noise with the planes flying overhead? Can I farm on my land? Should we worry about the water being contaminated? People worry about fishing access, and whether they’ll be able to access certain places in the water during training exercises. Will the ordnance disrupt the health of the environment and the water around us?”

The debate in Tinian has echoed across Micronesia since the Pentagon announced a new Guam-based military taskforce to coordinate defence operations in the northern Pacific.

As US media spruik the China threat, Ken Gofigan Kuper, co-founder of the Pacific Center on Island Security on Guam, says that his think tank aims to ensure that islanders themselves have a voice “amongst the cacophony that is geopolitical posturing.”

“Island security is very different from using islands for your security,” Kuper says. “We are trying to open up debate about what is considered islands security and believe much of the security conversation should be coming from islanders themselves, without having the terms dictated by Washington DC, by Beijing, by Australia.”

For Theresa Arriola, “it’s about re-framing the narratives about our islands. When you hear the word ‘strategic,’ let’s break that down. What does that mean? Do we want to engage with this level of military training because we’re being framed as strategic? What is that going to do to our environment and our culture in the long-term? These are all questions we’re grappling with.” •