Less than a year ago a little band of educators travelled to Canada to investigate why that country always seems to be ahead of Australia in the school achievement and equity stakes. The travellers agreed that it is time for different, more open “where to from now?” conversations about Australia’s schools. Their detailed report, including findings and recommendations, is now available.

To encourage new approaches the travellers linked with two very different organisations, Ellen Koshland’s Australian Learning Lecture, a refreshingly different social-reform think tank, and Leading Educators Around the Planet, which has long helped school leaders see best practice up close and bring it back to our schools. Both organisations and the travellers share a concern about the direction being taken by Australian school education.

They have good reason to worry. The differences between schools above and below the “average” index of socio-educational advantage, or ICSEA, are becoming very noticeable. The “above schools” (with an index of 1000 or more) are getting bigger and monopolising the headlines about school achievement. The “below” schools (1000 or less) are far less sought after and publicised. Public schools are enrolling more of the most disadvantaged. The drift of families who have choice has become a scramble from low- to high-ICSEA schools in all sectors, government, Catholic and independent.

Overall, NAPLAN scores have changed little over time, but they have markedly fallen in the “below” schools. A study of the link between student/school ICSEA and NAPLAN achievement shows that family background, ahead of what schools and teachers do, has an increasing grip on student achievement. On equity grounds alone it is a dismal picture for a country that prides itself on a fair go for all.

In searching for solutions it helps to know some of the background: how the problems evolved, how they feed off each other, and why intervention is needed.

Until recently school funding has been the highest-profile issue. The Gonski recommendations about school resourcing didn’t fare well under changing governments and endless fiddling, including by the states and territories. Federal Labor has restored a pathway to full funding of public schools, but the rollout is delayed, and we’ll have to hope that history won’t repeat itself.

But even if the funding does arrive, decisions made in the past will still act as a drag on both equity and achievement. Dean Ashenden told the whole sorry story recently in Inside Story. Researcher Barbara Preston has shown how the very unlevel school playing field, still firmly in place, has affected schools. In Choice and Fairness: A Common Framework for All Australian Schools, Australian Learning Lecture confirms the problems, but also points to a solution.

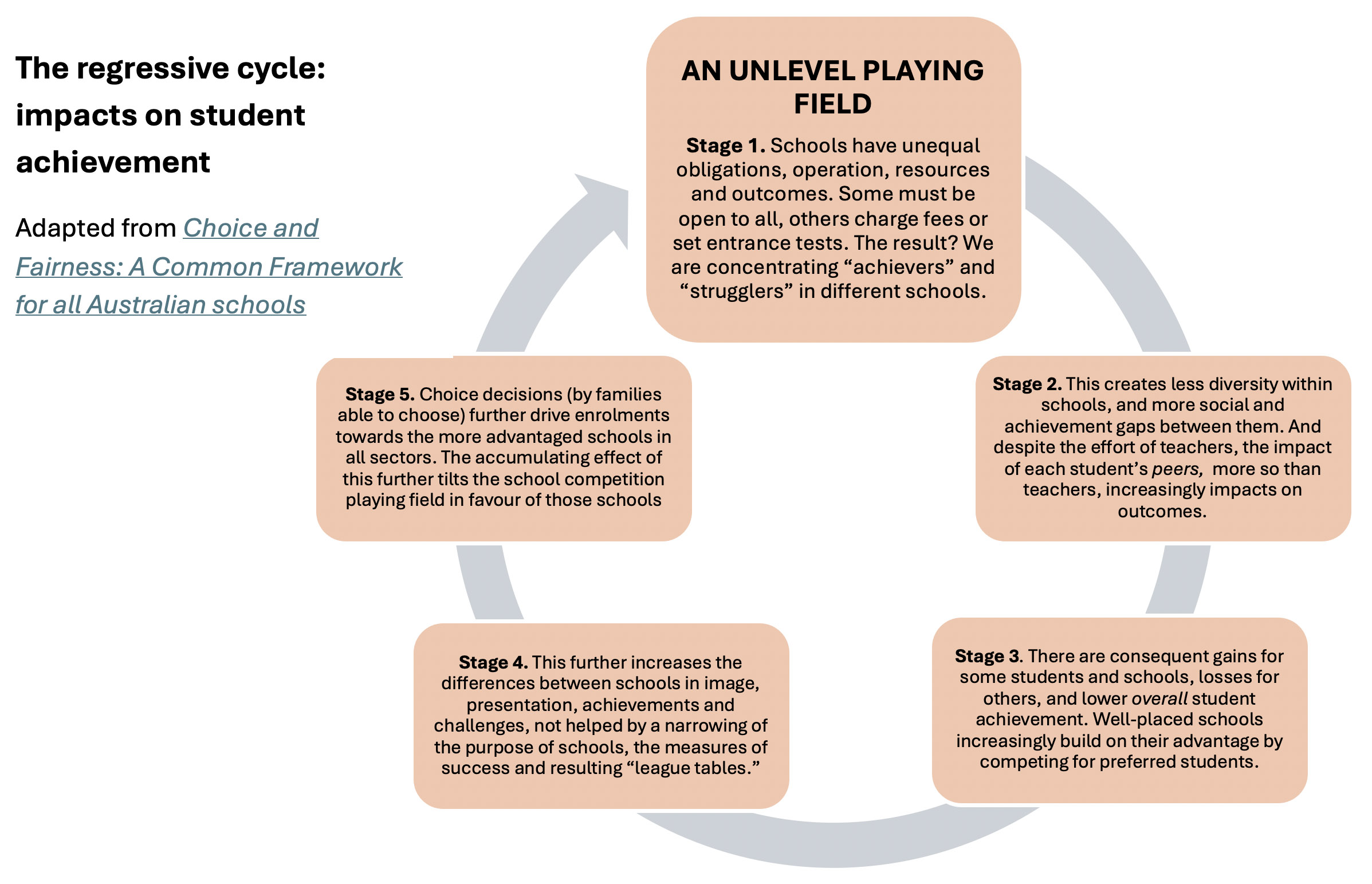

What is really wrong with Australia’s schools, and why do we need to search high and low, at home and abroad, for solutions? The most noticeable indicator is enrolment segregation and its impacts far and wide. The diagram below helps explain how, at the level of schools and families, Australia’s segregating school framework is seemingly locked into a vicious cycle.

Screenshot

This regressive sequence plays out in just about every Australian community and pervades conversations about schools, teachers and — in the better-resourced families —school choice. Even casual observers can see the links between the stages in the cycle and how schools fare in what has become a very lopsided competition. It looks like a system designed to create winners and losers.

Many of these problems, along with half-hearted solutions, have found their way into official reports. These include a 2023 Productivity Commission report on the National School Reform Agreement and a review, commissioned the same year by Jason Clare, to inform a better and fairer education system. The latter’s report is essential reading: it argues that the growing segregation of school enrolments needs to be tackled not least because the extent of segregation is making it less likely that other reforms will achieve Australia’s longstanding ambition of equity and excellence.

The other feature of the regressive cycle is that it is fuelled by assumptions about school quality. Dean Ashenden’s book, Unbeaching the Whale, points the finger at Labor’s “education revolution” and how successive governments have insisted that schools serve a narrowing range of priorities, reinforced by measurable student outcomes. It’s hardly surprising that families at stages four and five of the cycle become very fussy about their preferred school.

The persistence of the cycle not only undermines both equity and excellence but also raises questions about efficiency and effectiveness. There have been no gains in the “winning” schools to balance the losses elsewhere. It advantages some families in relative terms, albeit at a dollar cost to them, and imposes an opportunity cost on others. And all this is taking place alongside the ever-present human cost of lost livelihoods and disconnected young people, families and communities.

School reform is a “busy” response to all this but doesn’t deal with the fundamentals of the cycle. The most common interventions have tried to improve inputs (funding, for example) near the top of the cycle or close the gaps between schools at stage two by reforming classroom and school practice. But it hasn’t worked, and we are still left with a wicked problem wrapped in a vicious circle. Few reformers want to touch an unlevel playing field that requires only public schools to be free and inclusive.

The dimensions of the problem are harder to avoid. Browbeaten by growing concern, the 2023 review even commissioned research on how make schools more socio-educationally diverse and ensure affluent and non-affluent students don’t grow up strangers to each other. More recently, a former education system head, Michele Bruniges, gathered, assessed and reported on new ideas to reduce concentrated disadvantage in our schools, and ways to improve equity across them.

It is certainly possible to intervene at different stages to diversify enrolments within schools. Bruniges suggested adjusting school zoning to challenge the way postcodes concentrate both wealth and disadvantage. Michael Sciffer, one of the Australian team in Canada, shows how this can be done. Stage two in the cycle would start to look different if public funding substantially rewarded schools for enrolling more students from targeted disadvantaged groups.

The problem is that solutions grafted onto a largely dysfunctional framework might not be resilient enough to fend off efforts to unwind even the most thoughtful interventions. In Canada, the Australian team found evidence of creeping compromises that worsened the prospects of equity and achievement. One Canadian province allowed many community schools to become selective. Another loosened the regulations around school choice of public schools.

This suggests the need for a more wholistic approach. Bruniges certainly stressed that we must rethink how we resource and structure our education system. The Australian Secondary Principals Association has a new focus on transforming systems, declaring that inconsistency and inequity in the way schools are regulated must be tackled. It is effectively calling for a new schooling accord with a common funding and regulatory framework to enable all schools to tackle entrenched inequities.

The Australian excursion to Canada and its newly released report has the potential to inform these conversations by clarifying what might be gold-standard policy options while gently dismissing ideas that won’t make enough difference in the Australian context.

Lessons from Canada: An Equal School System is Possible asks if there is a better way to design our school system. After all, Canada and Australia are similar societies with different educational outcomes. The report makes eight significant findings derived from a close look at three quite different provinces. It concludes that solutions are possible, and outlines the steps towards a more equal school system.

One province started diversifying its provision of schools in the 1970s, the same decade in which Australia unwittingly launched what became our regressive cycle. This particular Canadian province put in place regulations and conditions that have generally stood the test of time — to the point where the province has achieved a reasonable public/private balance in the provision and operation of schools.

The reader might ask why we don’t do the same. Some of the regulations and conditions, if implemented in Australia, would improve our framework of schools. But they would fall short of an optimum solution. We can do better.

We could identify strongly with another province, but for all the wrong reasons. Just like Australia, this province has stumbled into serious equity problems. Quite uniquely in Canada, it substantially funds private schools — but as equity problems grew it then allowed many public schools to become selective. It could be argued that Australia and this province are competing in a race to the bottom. There is, however, one important difference: a parent-driven organisation in that province has come up with a plan for a common school network that has shifted public opinion and been drafted into possible legislation. Watch this space.

In common with a number of countries, a third province already has a fully funded framework of schools, with both secular and Catholic schools operating under almost identical obligations and responsibilities. All schools are resourced according to need and are regulated on a consistent basis, but they are diverse in character, curriculum, ethos and governance. No school, including Catholic schools, is allowed to charge fees, and fee-charging schools are only found in the small private sector. Variations of this approach are found in other Canadian provinces.

Smart educators know that it isn’t easy or even necessary to transplant school system reforms from one place to another. But Australia has done worse than that. Our response has been to shut our minds to the world beyond the level of each school. It’s not working. It is time to swallow our pride, take the blinkers off and learn from those who just might be doing better. •