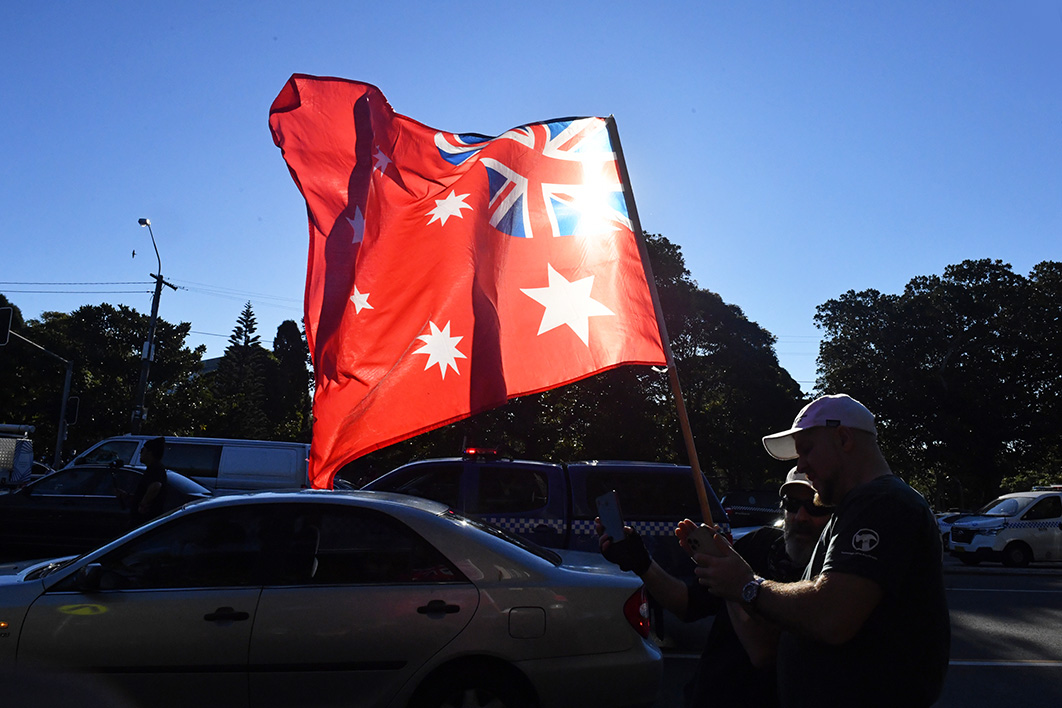

This week’s shocking violence in the small Victorian town of Porepunkah has shone a spotlight on the potential threats to police posed by “sovereign citizens.” But this movement has a much broader reach. From family law disputes to local council meetings, its adherents do their best to frustrate and delegitimise the state and its legal institutions — police, parliament, local councils — and even to replace public institutions with their own.

“Sovereign citizens” — a term that emerged in the United States in the early 1990s — exist at the intersection of several overlapping far-right political and religious movements that percolated across America and then spread to other democracies. Today, the descriptor is an umbrella term for a broad and diverse group of people, hostile towards government and authority, who believe laws don’t apply to them without their consent.

At the core of their beliefs is what those who study this phenomenon call “pseudolaw,” a radical reinterpretation of law based on adherents’ strange and bewildering legal theories. They may maintain that Common Law overrides legislation (in reality it is the other way around), that the Magna Carta is directly enforceable, that traffic regulations only apply to “commercial drivers” and that one’s “legal person” is distinct from the “living man.”

No sovereign citizen argument has ever been accepted by a court in Australia or elsewhere. Indeed, adopting these arguments often leaves the adherent in a worse position than if they had just paid the initial fine, a fact that is mysteriously omitted from the material promoters hawk on websites and through social media. But most adherents aren’t focused on winning in court; after all, they believe the courts are illegitimate. Rather, pseudolaw is the means for them to reject legal authority and attempt to assert their own power.

Many readers would have first encountered sovereign citizens during the Covid-19 pandemic. But the evidence suggests that pseudolaw had reached Australia long before 2020. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, for instance, several prominent American pseudolaw “gurus” toured Australia hosting seminars on how to opt of legal obligations. As far back as 2011, the Sydney Morning Herald suggested that one American pseudolawer, David Wynn Miller, made “hundreds of thousands of dollars” from a visit to Australia.

Scholars examining the rise of pseudolaw in Australia have largely focused their attention on its impact on the administration of justice. While much of this commentary is anecdotal, a recent study from South Australia (which we were involved in) confirmed that Covid-19 inspired significant pseudolaw litigation.

Judges, magistrates and staff described how pseudolaw claims increased workloads by generating hours of work dealing with issues that should take minutes and creating large volumes of paperwork with little relevance to the issues at hand. They also reported intimidating behaviour: adherents bringing supporters to the court, threatening to sue the magistrate or judge, videotaping court staff and even following staff out of the building. Pseudolaw clearly wastes time and slows down systems, and can intimidate and destabilise. The cost in resources and pressure on staff are significant. One judicial officer told us that he was seriously considering retirement.

While police and judges stand on the front line of the pseudolaw challenge, sovereign citizens cause problems for all official bodies that intersect or engage with the public. Local governments and councils are particularly vulnerable: they are the most easily accessible level of government and don’t enjoy the same level of protection as prominent public figures and state and federal officials. Some pseudolaw adherents have taken advantage of this by disrupting council events.

In 2023, fifteen councils across Victoria reported that members of the pseudolegal organisation My Place disrupted their meetings and activities. According to the Municipal Association of Victoria, anti-government groups like My Place targeted councils because “you can turn up to a council meeting. You can’t turn up to state parliament [and ask a question].”

Similar incidents have occurred in South Australia. In January 2023, the ABC reported, a City of Onkaparinga council meeting was adjourned and police called after several protestors wearing “body cameras and GoPros” to film their interactions “charg[ed] towards the council chambers.” Later that month, around seventy No Smart Cities Action Group members protested at the City of Salisbury council chambers, forcing police to expend significant resources to protect the safety of councillors. Some councils in Australia and New Zealand have been forced by death threats to institute new lockdown procedures. Others have moved public meetings online.

The week’s shootings in Victoria demonstrate the threat of pseudolaw at its most extreme. More common, however, are prosaic efforts to frustrate the effective administration of governance. This can be as simple as refusing to pay council rates. Just as adherents inundate courts with mountains of inappropriate documentation, local government authorities are pestered with groundless correspondence.

As one South Australian law firm noted in 2023, these actions place local government staff in difficult positions. Eventually, they are forced to commence debt recovery proceedings, but given that process generally begins in the small claims divisions of magistrates’ or local courts, where legal representation is permitted only in special cases, council officers must appear and engage directly with pseudolegal adherents.

Some pseudolaw adherents refuse to seek approvals for work on their homes and property. While councils have successfully acted in some cases, each instance requires authorities to waste scarce resources investigating whether an infraction should be prosecuted.

In what is perhaps the most disturbing development, some pseudolaw adherents establish their own courts and judicial systems. These courts regularly indict and try public officials (in absentia) and hound ordinary people through spurious court procedures.

In the small town of Warkworth, just north of Auckland, sits the New Zealand Common Law Court of Justice, a court run (as the name suggests) by pseudolaw adherents. Over the past few years, this fake court has tried prominent New Zealanders including then prime minister Jacinda Arden, her cabinet and advisers. Their offences? Committing crimes “against the Living Man” by requiring New Zealand residents to “receive an experimental medical procedure known as the Pfizer Covid-19 vaccination.”

Similarly, the Sovereign Peoples Assembly of Western Australia has issued verdicts against numerous public figures, including the then prime minister Scott Morrison, Commonwealth chief health officer Paul Kelly and premiers Daniel Andrews, Mark McGowan, Gladys Berejiklian and Annastacia Palaszczuk. These politicians and public health officials were sentenced to 120 years’ imprisonment for fraud, violating the Nuremberg Code (via medical experimentation), human trafficking and genocide.

These courts can’t enforce their verdicts, but they are not harmless. Their orders constitute threats against public officials. At least one individual in New Zealand has been jailed for such threats.

Ordinary people will feel the consequences more directly, however. Despite the references to “tribal” law on its website, the Australian group Nmdaka Dalai Australis appears to have been formed for the sole purpose of justifying child kidnapping. It created its own court and issued warrants for the arrest of a member’s ex-partner, demanding that he surrender his two sons to “court sheriffs.” As an ABC Investigations probe found, NDA sheriffs “deployed the threat of NDA’s bogus court as a weapon in family law disputes around Australia, harassing and intimidating judges, lawyers, officials and parents and children involved in custody battles.”

Pseudolaw is not simply eccentric nonsense. It is based on a worldview set on challenging and undermining democratic governance and delegitimising institutions. In rare circumstances, it is also used to justify violence, but most of its effects are rather mundane. It’s a slower, prosaic form of tedious disruption that clogs courts, interrupts proceedings, burdens councils and, in rare circumstances, intimidates staff.

Pseudolegal adherents are a classic example of the free-rider problem. Acting as though they are not subject to the law, they benefit from council services without contributing. Instead of collecting rates, local governments are forced to spend money enforcing compliance, draining and diverting resources from ordinary governance functions and increasing costs on others.

We originally expected pseudolegal activity to decrease with the diminution of Covid-era lockdowns and mandates, but it has shown incredible resilience. The question we face today is how public institutions can respond with systemic and coherent strategies that recognise both the everyday and the extraordinary threats pseudolaw poses without also forming the overbearing, tyrannical state that exist in the minds of its adherents. •