Let me start with a couple of incidents that illustrate the great political puzzle we now face.

Incident 1: On Thursday a number of tech billionaires had dinner with Donald Trump. They were nauseatingly obsequious — and completely insincere. Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg was asked how much money he plans to invest in the US and replied $600 billion. Shortly afterward, he was caught on a hot mic telling Trump “Sorry, I wasn’t ready… I wasn’t sure what number you wanted to go with.”

Incident 2: On Sunday Trump attended the US Open. When his face appeared on the Jumbotron, “fans unleashed a loud round of mostly boos,” the New York Times reported.

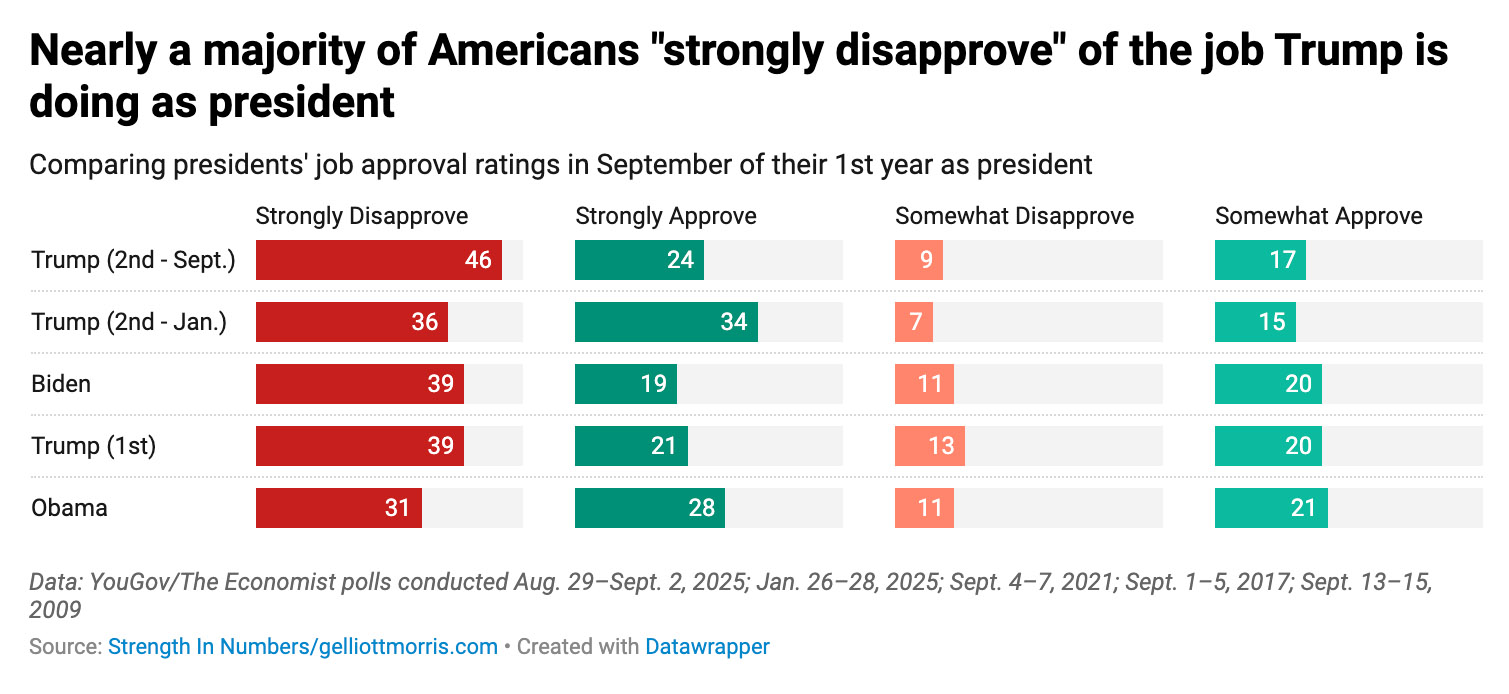

OK, this was in New York, not exactly MAGA country, but it wasn’t that much of an outlier. As G. Elliott Morris points out in Strength in Numbers, what stands out in Trump’s polling isn’t just that a majority of Americans disapprove of Trump, but that almost half the country strongly disapproves:

The Trump administration is obviously attempting to follow the familiar playbook by which autocracies consolidate their power, effectively turning America into a one-party state where almost everyone accepts that resistance to the regime is futile and is afraid to show any signs of opposition.

And by and large America’s elites have offered no more resistance to authoritarian consolidation than a wet Kleenex. But historically, anti-democratic parties that establish lasting autocracies have done so with considerable initial support from the broader public. At least at first, they’re actually popular, especially because they deliver, or seem to deliver, major economic gains.

That’s not happening for Trump, at all. And the big question — to which I don’t know the answer — is whether a regime that inherited a good economy but ruined it and whose non-economic policies are deeply unpopular can still consolidate autocratic rule.

Let’s consider a couple of historical examples.

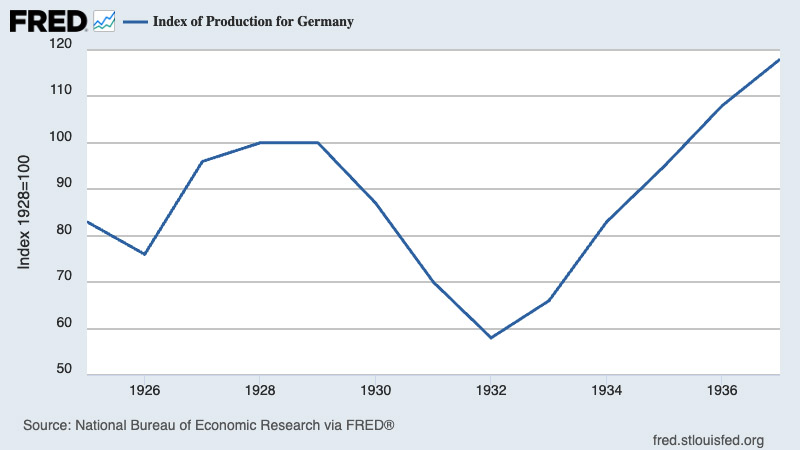

Adolf Hitler came to power in large part because the previous government insisted on following orthodox, deflationary economic policies in the face of the Great Depression. Hitler’s willingness to embrace heterodox policies helped Germany stage a strong recovery:

As a result, the Nazi regime was probably quite popular in its early years, when a public backlash might still have mattered.

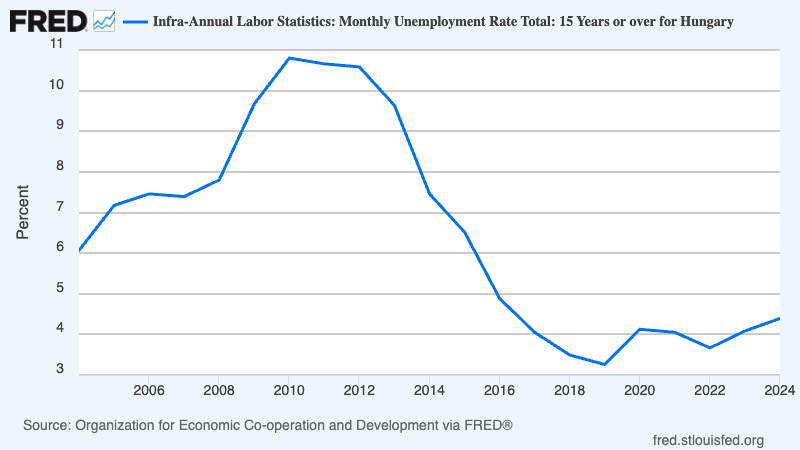

Fast forward to 2010, when Viktor Orban took power in Hungary. At the time, the Hungarian economy was deeply depressed, in part because of austerity measures imposed by the International Monetary Fund. Orban sent the IMF packing, and was able to preside over rapid economic improvement, with unemployment falling quickly:

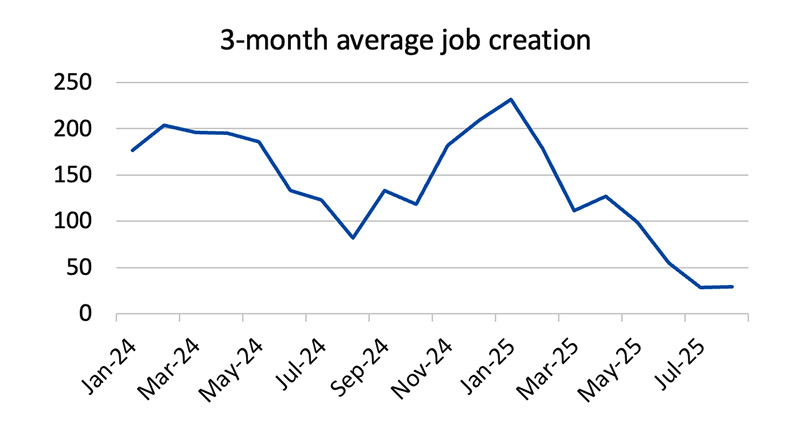

By contrast, Trump inherited an economy in good shape — even if the vibes were bad — and appears to be running it into the ground. Here’s the three-month average rate of job creation (which will probably look worse after this week’s regularly scheduled annual revision):

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

And all indications are that consumers will soon begin to see large price increases caused by Trump’s tariffs and, eventually, deportations.

Greg Sargent reports about one recent poll that asked likely voters how tariffs have affected their personal economic situation: 48 per cent say that they have hurt, while only 8 per cent say they have helped.

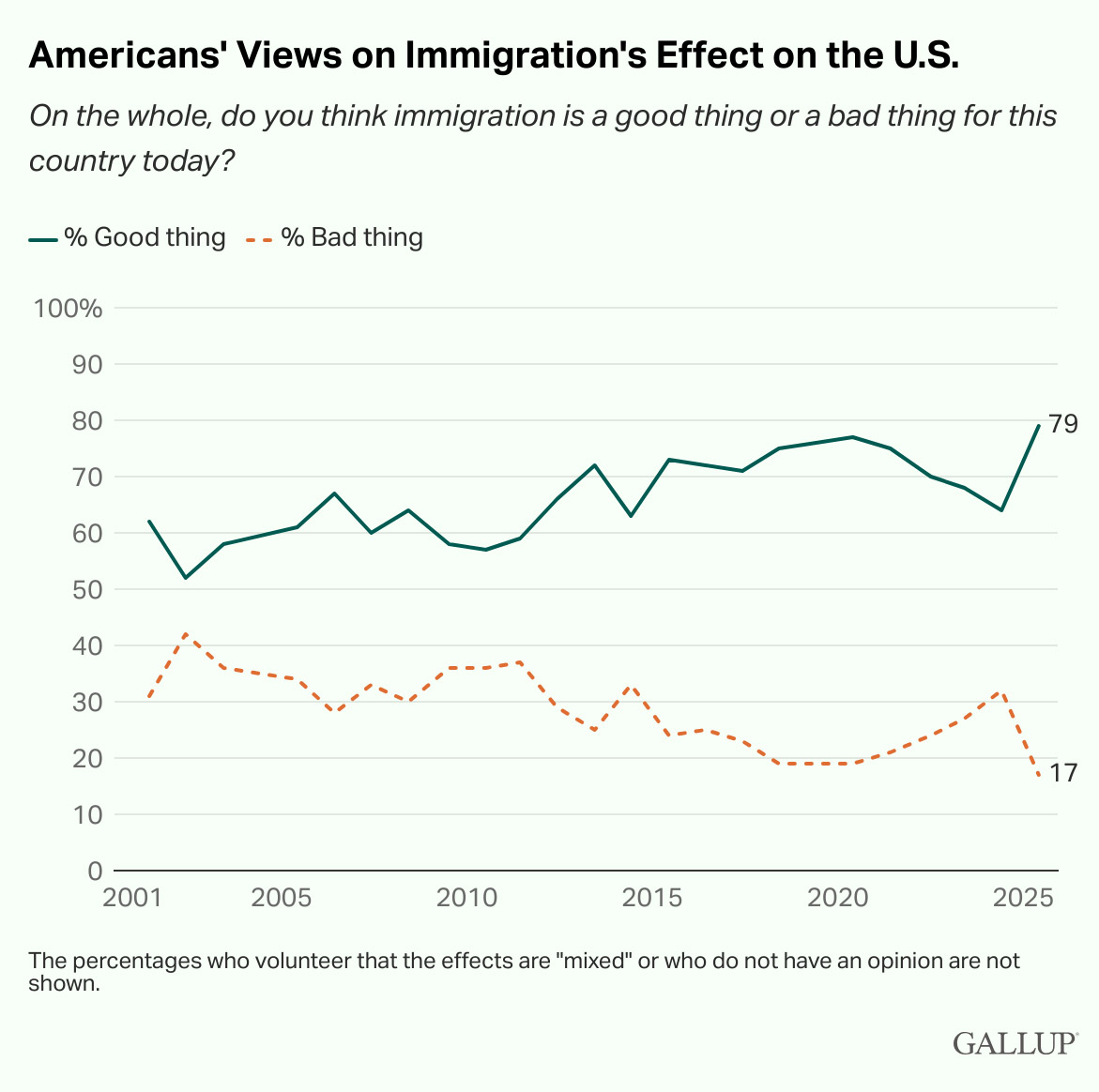

Can Trump compensate for the public’s dismal view of his economic policies by playing up culture-war issues like hostility to immigrants and anti-vaccine sentiment? Alas for Trump, these issues actually work against him. Belief that immigration is a good thing for America has hit a record high:

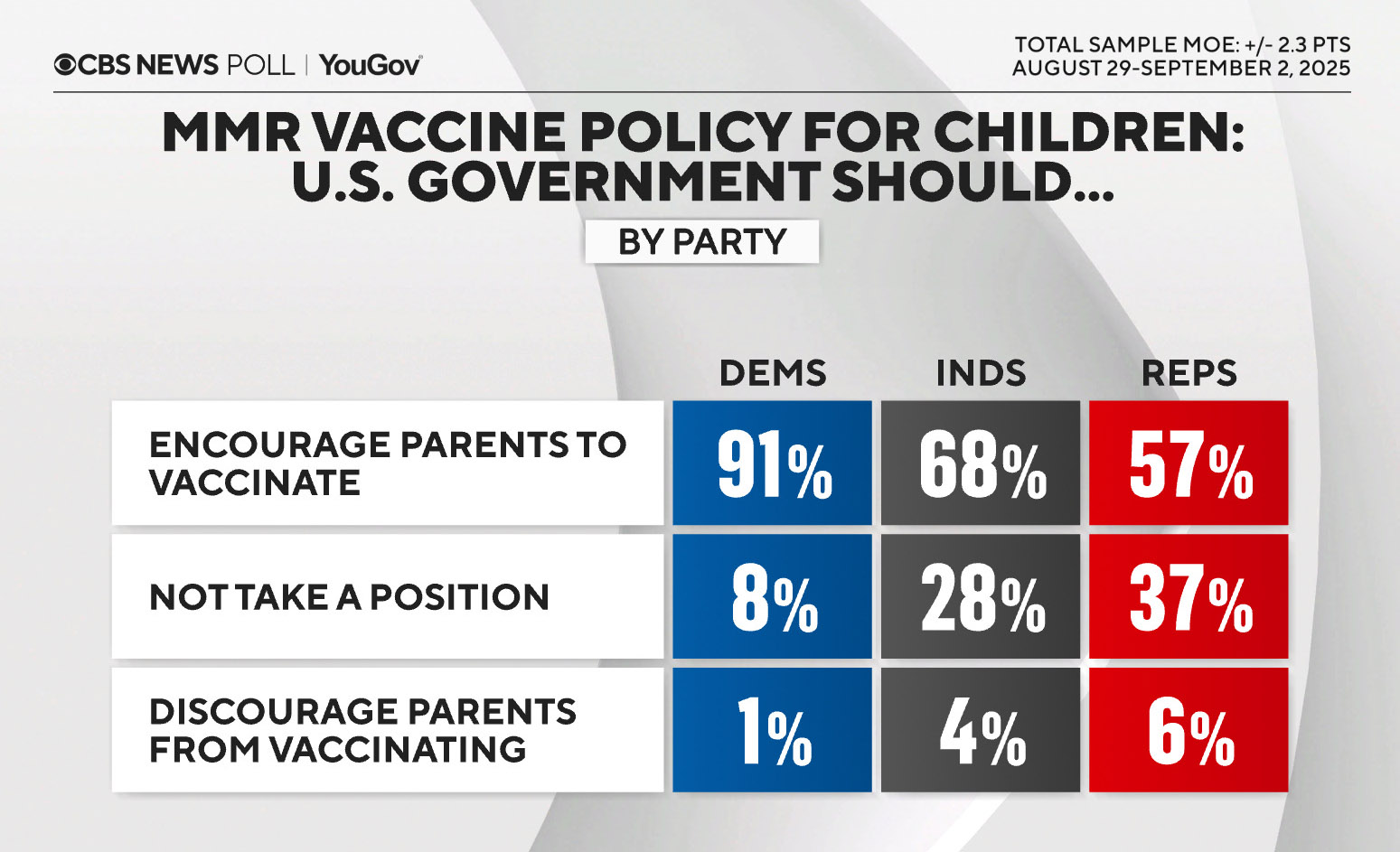

And anti-vax policies are wildly unpopular:

Roughly speaking, the American public doesn’t support anything Trump is doing. Yet he has been governing as if he has an overwhelming mandate to do whatever he wants, and to a large extent has been getting away with it. How is he managing that?

Part of the answer is anticipatory compliance on the part of members of the elite, from corporate CEOs to university presidents to law partners. Many of our institutions have been giving in to demands that Trump clearly has no legal right to make, out of fear of the consequences if they don’t.

Part of the answer is that Trump keeps declaring various kinds of emergency and then claiming that he has extraordinary powers to respond to these supposed emergencies.

Lower courts keep ruling against these claimed powers. For example, two courts have now declared Trump’s invocation of the International Economic Emergency Powers Act — the basis for 70 per cent of Trump’s tariffs — illegal. But the Supreme Court keeps overturning these lower-court rulings, as it just did in allowing Immigration and Customs Enforcement to resume indiscriminate stops in Los Angeles based on nothing more than ethnicity.

But are cowardly elites and a compliant Supreme Court that keeps granting emergency powers enough to let a president who has not yet established a widespread climate of fear, who has low and declining public support, consolidate his position as autocrat?

Honestly, I have no idea. But I guess we’re going to find out. •

This article first appeared in Paul Krugman’s Substack newsletter.