At the end of his travels through the Melanesian world this month, Anthony Albanese finishes up in the region’s biggest nation, the one shaped and launched by Australia exactly five decades ago, on 16 September 1975.

There, in Papua New Guinea, he will find signs of the Australian legacy, from the love of Rugby League football and the felt hats, moleskin trousers and elastic-sided boots favoured by its politicians to the institutions and notables welcoming him: a Westminster-style parliament, a governor-general representing the distant monarch, the bewigged justices in their new court centre.

But after encountering nationalistic prickliness in Vanuatu and the Solomons, the Australian prime minister will find the power dynamics between the Australian parent and the grown-up Papua New Guinean child greatly changed by the decades. Generosity and friendliness remain, but Canberra’s efforts at guidance are more and more tentative, if they’re made at all.

Even when PNG was staggering from successive political and fiscal crises in 2004, John Howard’s naive attempt to intervene by inserting 210 police and sixty-eight treasury officials to clean up PNG’s corruption met insurmountable objections. A court case challenging the immunity Howard wanted for the Australians marked its end.

From then on, buoyed by a resources boom, prime minister Michael Somare’s relations with Howard were testy. In 2011, his successor Peter O’Neill leveraged Kevin Rudd’s scheme to park boat people on PNG’s remote Manus Island to get Canberra off his back. “By then Australia’s brief attempt to exercise policy influence had come to an end,” say the authors of Struggle, Reform, Boom and Bust, a new ANU study of PNG’s economic record since independence.

The Manus deal marked a new phase in Australia’s relations with PNG — a phase “in which power shifted from the former to the latter.” The scales tilted further from around ten years ago, when China began looming much larger. “PNG was increasingly viewed in Australian policymaking circles through a China lens,” write the ANU researchers, led by economist Stephen Howes. “What mattered from this perspective was not whether Australia was having a beneficial impact on PNG but simply whether it was popular. While budget support was again provided in the most recent period, this time it came with less onerous conditions.”

Over the early decades of PNG’s independence, Canberra had shifted its economic support from general contributions to the PNG budget to more specific program aid, tying funds to projects rather than letting PNG ministers and bureaucrats decide how to spend them. Since 2019, under Scott Morrison and then Albanese, Australia has provided the PNG Treasury with swathes of soft loans — nearly A$3.2 billion over five years — free of what the researchers call the “onerous and controversial policy conditions” of previous eras.

In return, Albanese has persuaded PNG to look to Australia and its allies first for defence and security arrangements. But the issue isn’t straightforward: Australia’s northern neighbour still has about 20,000 Chinese residents (as against about 10,000 Australians), most of them recent migrants, as well as numerous Chinese state-owned enterprises ready to undertake projects at cut-throat prices.

That geo-political game will continue. But there is another kind of security question, one about PNG’s inner resilience and the prospects for improvements in wellbeing and livelihoods. Aside from the benefits for ordinary citizens, it is these that will create the strength PNG needs to resist malign influences and engage more with the world.

Behind the big projects that make PNG one of the most resource-dependent countries in the world — with gas, oil, gold, copper and nickel making up 32 per cent of GDP in 2022 — the government’s performance has been lacklustre. The result has been a dual economy, the ANU study shows, with the benefits going to the better-off strata of the urban populations.

The rural 85 per cent of PNG’s people have seen stagnation. Over the fifty years of independence, the annual growth rate of non-resource GDP per person has averaged just 0.4 per cent and the annual growth in formal-sector employment only 1.5 per cent. Life expectancy, literacy and school enrolments have continued to improve, but “non-income indicators” remain “alarmingly low by international standards and, in some cases, have worsened.”

The report continues: “In recent years, PNG has had the lowest rate of immunisation, the fourth-highest rate of child stunting [nearly one in two] and risk of premature death from non-communicable disease, and the seventh-lowest doctor–population ratio in the world [63 per million].”

As well as its fractured geography, ethno-linguistic diversity and rigid systems of customary land ownership, independent PNG started out in 1975 with some high-cost Australia legacies.

One was the floor on wages and civil service salaries, and their regular indexation, which Somare had won ahead of independence in 1972–75 with the help of Bob Hawke’s ACTU. Until it was unwound in the early 1990s, PNG had the highest wage costs in developing Asia, and those rates of pay encouraged thousands of hopeful villagers to Port Moresby. Their disappointment eventually added to the growing crime problem.

Another was the pegging of the new currency, the kina, to the Australian dollar, reducing the exchange-rate buffer that would have muted global price downturns for the coffee, cocoa and other tree crops that gave many households their only cash income. Despite different exchange rate systems and suspended kina convertibility, this remains a negative for all except the politicos protected from the consequences of running up budget deficits.

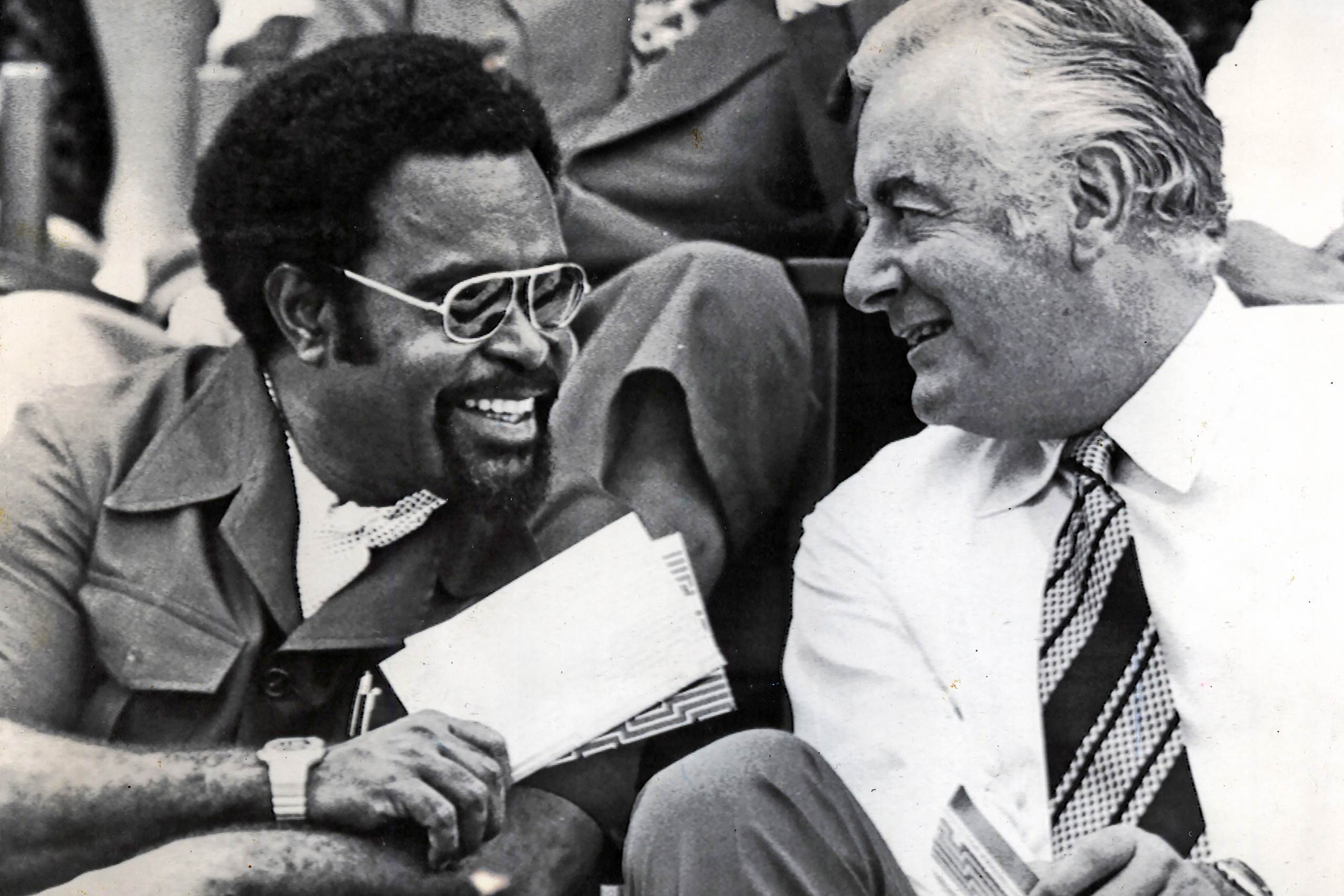

Dual economy: with the Ok Tedi mine’s copper-slurry loading dock in the background, villagers wait for canoes home after shopping in Kiunga’s Chinese-run stores. Hamish McDonald

The big copper mine opened by Conzinc Riotinto Australia on Bougaineville island also proved a time-bomb thanks to the Australian administration’s disregard for local land-ownership issues. The mine was providing half PNG’s exports at independence and much of the government’s revenue. But the locals wanted out of PNG from the start. In 1989 they closed down the mine and started a civil war.

New resource projects blossomed, meanwhile, pushing GDP growth up to 18 per cent in 1993. PNG no longer needs the Bougainville mine, but its leaders are still unwilling to endorse the express wish of 98 per cent of Bougainvilleans to have their independence.

Try as the ANU authors might to focus on economic policies, they can’t ignore politics and governance. As elsewhere in Melanesia, Papua New Guineans took to the Westminster system left by Australia like ducks to water. Then they muddied it in their own special ways. “Elections continued to be regularly held,” the authors say, “but a political culture of clientelism and precarity became entrenched, with MPs elected on the basis of local issues and a high rate of turnover of MPs every election.”

With increasing numbers attracted to politics, and with MPs’ business interests growing, “no distinction developed between the political and the business class. As parties weakened, politics became increasingly attractive, but as an arena for never-ending power contestation rather than for competing policies.”

Increasingly, MPs used their personal slush funds, allocated from the budget, to compensate for declining administrative services and build up their own prestige. Corruption scandals didn’t keep them out of action for long.

Meanwhile, crime and violence were making Port Moresby notoriously unsafe. That has moderated somewhat, but across the country local groups use real or spurious land claims to hold up projects. Modern high-powered guns turn up in fights between political support outfits and tribal groups across the populous Highlands.

There are bright spots, however. Alongside the unruly legislature, “judicial independence and integrity have been largely maintained and many look to the judiciary as a bulwark against chaos,” the ANU authors maintain:

And, indeed, the judiciary does play a vital dispute-settlement role, especially for the political class. The courts also provide a useful constraint on power. Since, given the lack of fixed party divisions, it is often not difficult to obtain the two-thirds parliamentary majority needed for constitutional change, politicians control the constitution except to the extent that the courts rule that constitutional changes are inconsistent with other parts of the original constitution.

The downside of this “regime stability” is that PNG is among the most litigious countries in the world. “This is costly, and slows down change, whether positive or negative, and development.”

It adds up to a political system that has proven unusually durable. Few developing-country regimes last more than twenty years without an unheaval of some kind. In contrast to the rapid turnover resulting from votes of no-confidence in early decades of independence, PNG’s governments have become more stable. Over the past twenty years, the country has had only three prime ministers, as against seven in Australia (or eight if Rudd is counted twice).

But while the state is stable, it is also weak. “PNG’s development outcomes can be explained by its hyper-politics and pervasive insecurity, and the feedback effects generated by the weak state and the low growth these two factors cause,” the ANU authors argue. “Political regime stability provides a positive countervailing force, meaning that the constraints on development in PNG have led, not to collapse, but to a weak-state and low-growth equilibrium.”

PNG has felt both the positive and the negative impacts of resource growth — the latter, an unbalanced economy, known as the “resource curse” among economists. “An increasingly resource-dependent economy is one in which a weak state becomes ever more important as a distributor of economic rents, and perhaps weaker as it is distracted from other policy challenges. It is probably also one that is even more prone to conflict. These feedback loops constitute Papua New Guinea’s institutional resource curse.”

Being economists, the authors rely on the available data. But they admit that not much is known about economic activity that goes unmeasured. Huge numbers of households seem to growing and trading betel nut, the narcotic chewed and shared for its mild uplift and impact on sociability. Many make and sell snacks, or trade home produce.

When the government relaxes its controls, private services spring up. The country may have only 5000 or so police for its 11.8 million population, but it has 31,000 registered security guards and numerous neighbourhood watch networks. When the state monopoly on mobile telephone services ended in 2007, Digicel expanded to more than two million subscribers. Responding with ingenuity, micro-insurance and other businesses took advantage of the new network.

This non-government energy perhaps explains why Papuan New Guineans appear so stoic despite a political system that hasn’t yet tackled pressing, deep-rooted problems, including how to put traditionally held land to modern uses, how to better protect individual safety and property, and how to direct resource earnings to general welfare.

“Many things have got worse, and there are certainly serious risks,” say the ANU authors, “but, so far, the pessimism of the doomsday merchants has been as misplaced as the optimism of PNG’s boosters.” •

Struggle, Reform, Boom and Bust: An Economic History of Papua New Guinea Since Independence

By Stephen Howes, with Martin Davies, Rohan Fox, Maholopa Laveil, Manoj Pandey, Kelly Samof and Dek Joe Sum | ANU Press | $79.95 print, or free download | 442 pages