Economic reality has a habit of throwing you curveballs — events you didn’t anticipate when making your predictions. Specifically, most economists, myself included, expected tariffs to be the big economic story of 2025. After all, in just a few months Donald Trump has reversed ninety years of pro-trade US policy, sending average tariffs to their highest level since 1934. Predictably, supply chains have been disrupted, consumers face higher inflation, and farmers can’t sell their crops abroad.

Yet the economic consequences of the radically self-destructive turn in US trade policy have been matched, perhaps even overshadowed, by a development that has nothing to do with policy: an enormous surge in spending on “AI.” Scare quotes because ChatGPT and its rivals aren’t really artificial intelligence. But they are impressive, routinely doing things that would have seemed impossible just a few years ago.

And the surge in AI investment — a tech boom the likes of which we haven’t seen since the 1990s — has buoyed the economy in the short run, offsetting the drag from Trump’s tariffs. Without the data-centre boom, we’d probably be in a recession. But hundreds of billions in spending on data centres have boosted investment, while soaring stock prices have supported consumer spending by the wealthy even as demand from lower and middle-income Americans weakens.

Unlike the tech boom of the 1990s, however, the current AI boom isn’t translating into widespread economic optimism. In fact, Americans are remarkably downbeat about the economy and the future in general. And I think it’s worth trying to understand why.

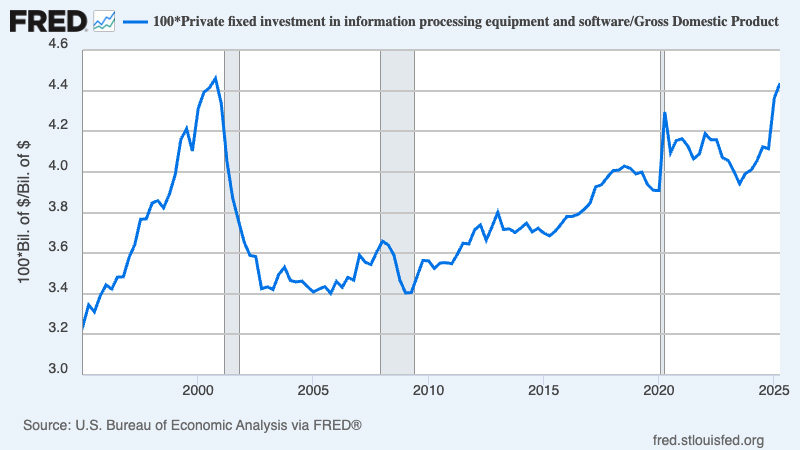

This article isn’t about the long-run consequences of AI for things like jobs and economic growth, as well as whether we’ll soon create superintelligences that decide to kill us all. I want to focus for now on how hopes about profits to be made from AI — and fear of missing out, or FOMO — have led to huge business outlays, largely on those data centres. By the second quarter of this year spending on information-processing equipment and software, as a percentage of GDP, had already matched its peak in 1999, the height of the internet bubble. There’s every indication that it’s going to go even higher, maybe much higher.

Source: St Louis Federal Reserve. Note: Ignore the numbers for the early 2020s, which, like so many other things, were greatly distorted by Covid.

The current AI boom resembles the 1990s tech boom in other ways besides the tidal wave of spending. To those of us of a certain age, the hype — This will change everything! — is distinctly familiar. Now, as then, the feverishness is a good reason to suspect that we’re in the midst of a huge speculative bubble. Reinforcing this suspicion is the fact that big tech companies, which generate billions in cash flow, are spending more on AI than their gushers of dollars can support. So now they’re taking on lots of debt.

While the 1990s and today are alike in their bubble mentality, however, they differ in an important way: today we lack the pervasive optimism of the late 1990s. It’s hard to convey to people under the age of fifty just how upbeat Americans in the late 1990s were feeling about the economy and the future in general. In fact, I believe the Bill Clinton–era boom led Americans to take prosperity for granted, resulting in their willingness to switch their presidential votes to a Republican — the ill-fated George W. Bush.

Today corporations are, once again, pouring vast sums into technology, but they’re doing it against a background of extraordinary pessimism. And the question I want to ask is why we’re seeing 90s-type hype without a return of 90s-type hope. Why aren’t we partying like it’s 1999?

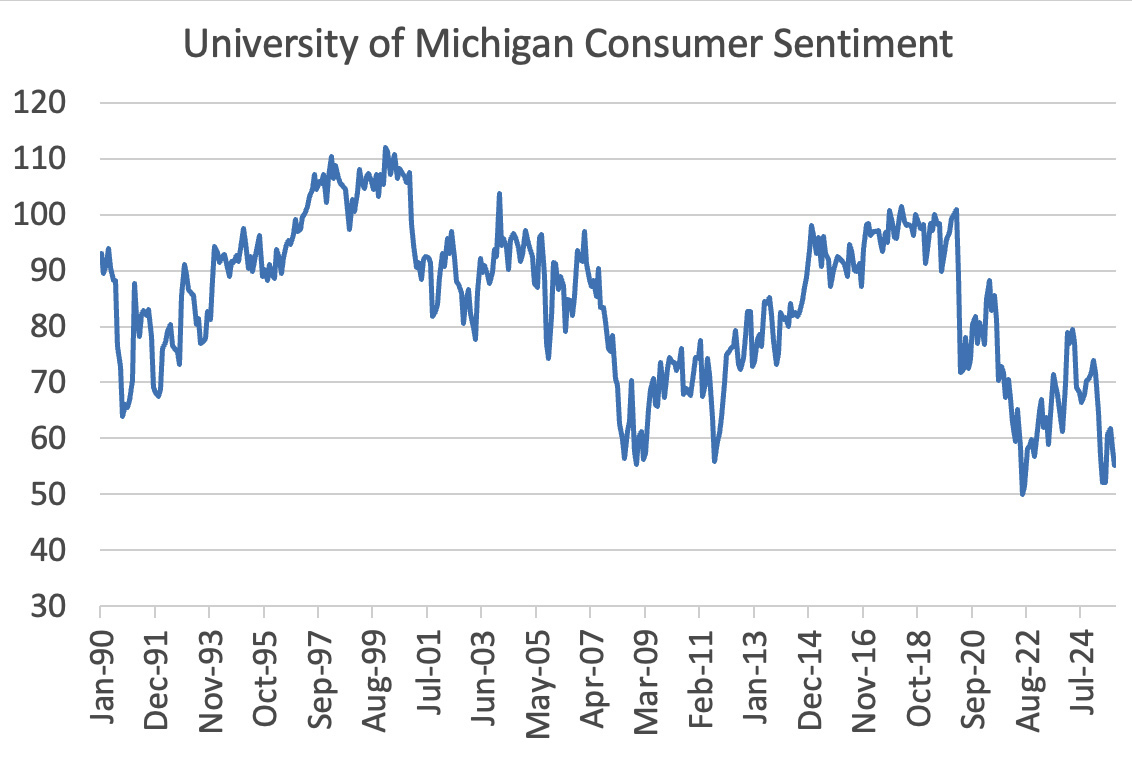

You can see the difference in how people feel about the economy by looking at consumer sentiment, which was very high at the end of the 1990s but is now about where it was during the depths of the global financial crisis:

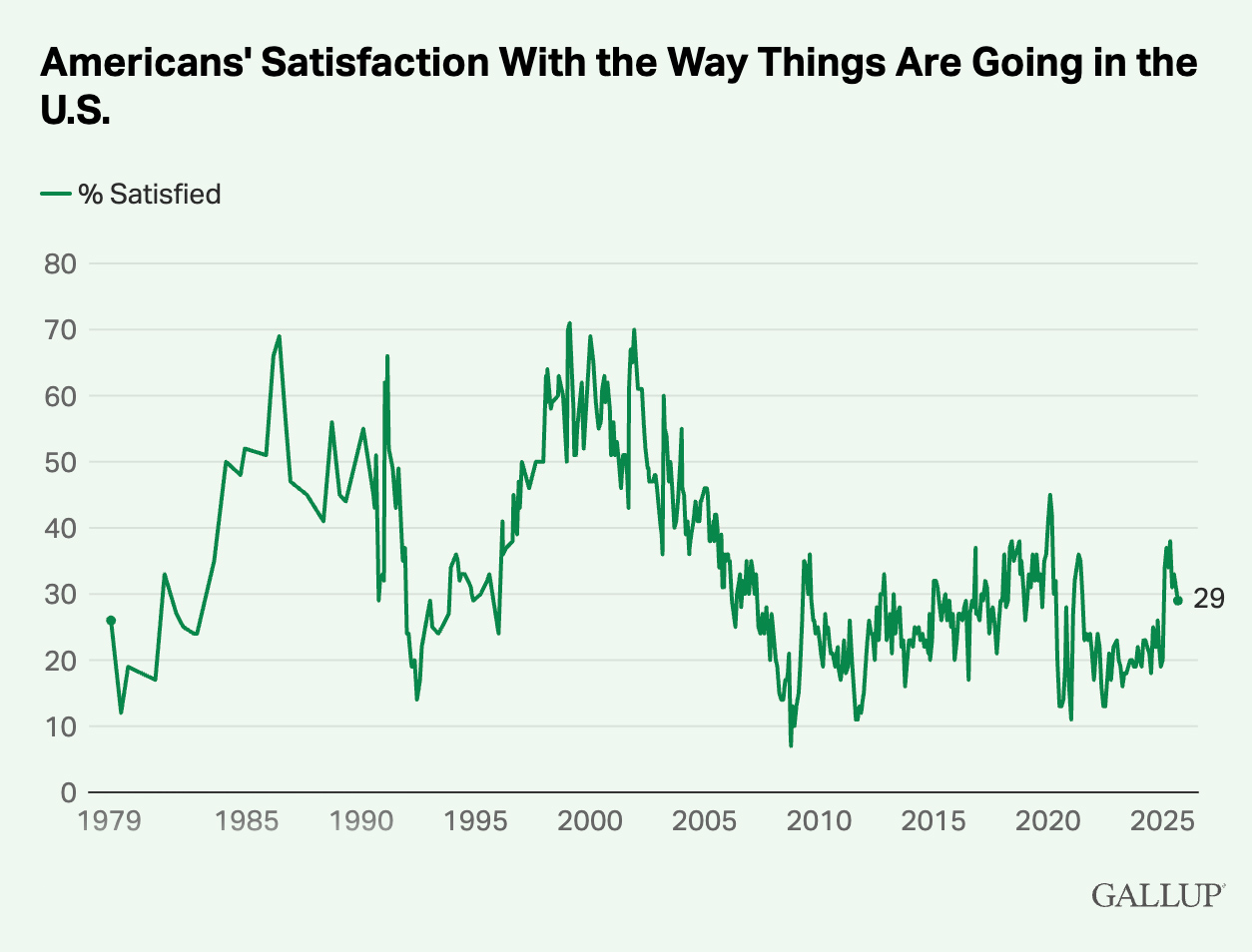

You can also see the difference between now and then in more general polling. In 1999 around 60 per cent of Americans were satisfied with the way things were going in the country; these days it’s half that. You can see it in presidential approval ratings: In March 1999, 78 per cent (!) of Americans said they approved of Bill Clinton’s handling of the economy. Polls show Trump with less than half that much approval for his economic policies, with those disapproving exceeding those approving by around fifteen points.

So why are we all feeling so grim even as businesses place huge bets on an impressive and possibly transformative new technology? I’d give three answers.

First, the US economy under Trump is doing worse than the standard measures indicate. It’s true that we haven’t had a recession — largely because that huge spending on data centres has compensated for the economic drag caused by tariffs. It’s also true that unemployment remains fairly low — in fact, the current unemployment rate is similar to the unemployment rate in 1999.

But while we haven’t (yet?) seen mass layoffs, the labour market is weirdly frozen, probably because of uncertainty created by Trump’s erratic policies. The hiring rate — the rate at which employers are taking on new workers — is very low by historical standards. So is the quit rate, the rate at which workers are voluntarily leaving jobs, normally an indication that workers fear they won’t be able to get a new job if they leave their current employment.

Unfortunately, these data don’t go all the way back to 1999. But here’s a striking comparison. The Conference Board [a business-oriented think tank] conducts a monthly survey of consumer confidence that among other things asks whether respondents consider jobs “plentiful” or “hard to get”. In April 1999 people were very upbeat about job-finding: 47.4 per cent said jobs were plentiful, while only 12.5 per cent said they were hard to get. In August 2025 those numbers were 26.9 per cent and 19.1 per cent respectively, a far more pessimistic view. In other words, not many Americans have been laid off, but many of them are very worried about what will happen if they do lose their job.

Which brings me to my second point. As best I can remember, people were excited about the rise of the internet but not, for the most part, frightened. They saw new possibilities opening up, but few Americans saw these new possibilities putting their jobs or their society at risk. In retrospect we should have been worried: social media in particular have done an immense amount of social and psychological damage. But we weren’t thinking about those risks.

By contrast, it’s hard to find people who aren’t worried about AI. It’s common to hear warnings that AI will eliminate large categories of jobs, and maybe even lead to mass unemployment. I take the first prospect seriously — past technological change has taken away most of the jobs in major occupations, from coal-miners to longshoremen. As a card-carrying economist, I’m sceptical about the second: people have been predicting mass unemployment caused by automation since the 1930s, and it keeps not happening. But the point is that AI is creating widespread anxiety even as it boosts GDP in the short run.

Finally, although this is hard to prove, I believe the political situation is bleeding into economic perceptions. People like me see a terrifying autocratic power grab in progress. While Trump and his minions claim that this is the BEST ECONOMY EVER, they also claim that our major cities are war zones overrun by dangerous leftists, which kind of interferes with the attempt to project sunny optimism.

My guess is that the current tech boom, like the 90s boom, will end in a painful bust. While Trump keeps insisting that the economy is great, his minions have taken to promising that it will get much better next year. Given how bad people are feeling about an economy currently propped up by an unsustainable tech boom, I wouldn’t bet on it. •

This article first appeared in Paul Krugman’s Substack newsletter.