I’m midway through a bizarre project. I’m trying to find out who my father was. I’m not adopted or a foundling. I lived with my father until I left home in my late teens and I was with him when he died ten years later, in October 1990. I knew his name and his occupation: George H. Nadel, historian. But I grew up not knowing his real story, and so, by extension, not knowing my own.

There are millions who have stories like mine. Many are more dramatic and just as worthy of exploration, but most remain untold. As a writer, I have had the privilege of being able to explore my story, and I share it to shed some light on the impact that political decisions wreak on the emotional lives of those they affect.

I was born in the United States but grew up with my sisters in a beautiful house in the south of England. It was set on acres of its own woods and gardens. The entrance was by one of two long drives, each of which bore the signs “Keep out. Trespassers will be prosecuted.” I was the eldest of three girls and we were surrounded by material plenty but lived in what as an adult I now know to be emotional deficit.

Our parents occupied the formal side of the house while my siblings and I had our own zone. We rattled around in our large quarters, haunted by the absence of meaningful connection with our parents. We ate meals in front of the television in the playroom. The walls were decorated with somewhat bleak quotes that my father had encouraged us to write out in calligraphy, and they provided the emotional backdrop for our youth.

There are two in particular that I remember. The first is from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra:

O, withered is the garland of the war;

The soldier’s pole is fall’n; young boys and girls

Are level now with men. The odds is gone,

And there is nothing left remarkable

Beneath the visiting moon.

And the second from my father’s favourite poem, Yeats’s “The Second Coming”:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Despite, or maybe because of, those prophecies of doom, I buried myself under my covers, listening to love songs on pirate radio at night and finding comfort in the now horribly dated Enid Blyton novels, full of clichéd and loving English families. I don’t remember being hugged, complimented or affirmed as a child. How reliable that memory is I don’t know, but I do know I longed for affection.

I can remember one day begging my father to tell my mother that he loved her. He refused. “There’s no such thing as love,” he explained with the tone of contempt that he reserved for anything he classified as idiotic.

One of the few games I can remember playing with him was “broken chair.” We would sit on his knee, not knowing at which moment his legs would separate, leaving us crashing to the floor. The thrill of being close to him was enough to ensure that no number of falls would make us lose interest in the brief intimacy it offered.

I worshipped my father and longed to be close to him. When I was brave enough, I would creep out of the playroom, through the living room and to the entrance of his large book-lined office, where he’d sit typing on one of his two typewriters. A thick velvet curtain hung across his door. We weren’t allowed into his study, nor to ask for entry. But the tap of his fingers on the keyboard was a welcome song, reassuring me he was there.

He was an academic, a historian who had taught at Harvard and Princeton and was working on his magnus opus — on the history of the philosophy of history, especially as articulated by Lord Bolingbroke. He also was editing the academic journal he’d begun while a student in the States. History and Theory was (and is) a prestigious journal that numbered luminaries like Ernst Gombrich and Isaiah Berlin among its board. As well, my mother would emphasise to us that my father was an English country gentleman.

It was a childhood with many rules. Obviously, we should be seen and not heard — this was England, after all. But most important was that we did not ask questions. Questions were considered the height of rudeness. For years into our adulthood my sisters and I would struggle to make conversation with outsiders. Without being able to ask questions, having a normal healthy dialogue with another human can be hard.

Of course, as children we wanted to know about our parents, and when we were brave enough we would beg our father to tell us about when he was little. His answer was always the same: “Well, when I was a little GIRL…” And he’d then spin a wonderful fairytale about his female childhood. He was a gifted storyteller and of course we longed for his tales, but more than that, we longed for the truth. He would not budge from his narrative, and when we professed disbelief that he’d ever been a girl he’d show us pictures of himself as a toddler in an elaborate lace christening robe that looked like a dress, which he claimed as proof.

Even his name was a mystery to us. We knew that in addition to being our Papa, he was called George H. Nadel. But what did the H. stand for? “Feet,” he’d tell us in a deadpan voice. It was only years later that we discovered the joke: his middle name was in fact Hans — definitely not a typical name for an English country gentleman.

In addition to questions being forbidden, we were not allowed to tell strangers anything about ourselves or our family. Strangers included the staff who helped raise us. There was one thing only that we were allowed to tell people we met in the village: that the three large Alsatians my father kept were trained to kill. “I only need to make one sound,” he’d tell us, “and they will pin someone to the ground and finish them off.” We dutifully told all our friends this, which could possibly be why playdates were few and far between.

There were other clues that all was not as it seemed in our outwardly “perfect” childhood. There were moments of what I would now call cruelty, though at the time I simply experienced these as painful and confusing events that illustrated something lacking in me. One time, on a walk with my father, I asked him if it was safe for me to balance on top of a thin bar at the top of a metal fence. “Of course,” he replied. So, I clambered up to try to impress him. The pole was thin, about the same width as a rope, and balancing impossible. Within seconds I’d fallen and cut my chin on the metal. My father laughed. How could I have been so idiotic as to even attempt such an impossible thing?

My father kept guns, which he used to shoot the rabbits and squirrels that threatened the plants on his grounds. I considered this to be murder. If I saw him leaving the house with his shotgun, I would run ahead of him, shouting to try to scare his prey away. He also used traps and would bring the unfortunate creatures he’d caught to his workshop, where he’d transformed a large plastic dustbin into a makeshift killing chamber. He’d put chloroform on cotton wool at the bottom, and would then push the animal in through a homemade hatch at the top. He would tell me he was putting them to sleep and it was for their own good. Later, I would be allowed to bury the corpses. Indeed, I had a small graveyard.

In the children’s section of the house there were murmurings among the staff. They frequently alluded to the existence of secrets: things we’d be horrified about if we knew, but ultimately were never told. Despite that, the nannies and cleaning ladies were warm, doing their best to make up for the absence of affection from our parents. I felt loved in their presence and I couldn’t fathom the hierarchies that kept their material circumstances so different from mine. I credit those early relationships for the socialist beliefs that have driven my adult life, and for giving me the strength, at the age of eleven, to refuse to be sent to boarding school, which would have been the norm for someone of my background.

By the time I reached my teens and had developed the courage and will to force questions on my father about his past and his childhood, he’d developed Parkinson’s disease. Plying him with unwelcome questions felt cruel when he was in obvious physical discomfort. Before long, it was too late: for the last decade or so of his life he was rendered largely incapable of speech. The glorious home we’d grown up in was sold and we lived in more humble circumstances, with a shared living room, close at last to our now dying father but still unable to reach him.

When I was eighteen, I travelled to Australia. While there I stayed with a college friend of my father’s, the economist Murray Kemp. He showed me a book my father had written as a doctoral student on the colonial culture of Australia. “It was so good it was used as a standard text for many years,” Murray explained. For the first time I realised that my father had had a past life in Australia. Before that, I had only a vague notion that he’d studied there before winning a scholarship to Harvard to complete his PhD, where he’d met and married my mother.

It was just before he died that I gained my first hard evidence that my father had a hidden past. Once discovered, it began to make some sense of his emotionally withdrawn nature, his fear and his insistence on privacy. And also, to some extent, of the flashes of macabre cruelty that I had occasionally witnessed.

By this time, my father was so sick that he’d been moved to a nursing home. There were only two words he managed to communicate, through a lengthy process of guiding a felt-tip pen on a pad of paper. These were “die” and “exit.” Before he’d become completely debilitated, he’d joined the voluntary euthanasia organisation EXIT. These contorted notes left us in no doubt that he did not want to live but, in 1980s England, decades before Dignitas and debates about assisted dying, we felt trapped by the law and utterly powerless to help.

As he was unable to talk, I got into the habit of reading to him. I was never sure whether he was following, but it helped to pass the time and we hoped it helped to distract him. Shortly before his death, I found a book by his bed in the nursing home. Publishers had continued to send him books for review, and my mother delivered these books and copies of journals to the nursing home, even though there was no possibility of his ever opening or reading them. This book, The Dunera Scandal, was written by Cyril Pearl and featured a twist of barbed wire on its cover. As the book explained, the Dunera was a transport ship commandeered during the war to carry “enemy aliens” from Britain to Australia. The episode had become a British national scandal because of the brutality with which the “enemy aliens” were treated.

The majority of the men on the ship were not enemies of the British state, but Jewish refugees who had fled Hitler’s regime to what they’d thought was safety in Britain. They then found themselves herded up, incarcerated and transported to an unknown destination alongside fascists and Nazi sympathisers. The British guards threw overboard many of the possessions the internees had brought with them, though not before pocketing valuables.

The book fell open on a page about a third of the way through, and I started to read to my father. It described how inmates on the Dunera were forced at gunpoint to run barefoot over broken glass. With his shaking, crippled hand he reached out to my arm to stop me from reading. He pointed first at the book and then at himself and I was sure I could see his lips forming the words, “That was me.”

It wasn’t until his death, when we went through his filing cabinet, that we found a second clue: an envelope marked “Destroy on my death.” We didn’t. It contained only a few documents, but enough to reveal a past our father had not disclosed. Born in Vienna, he was Jewish and had fled alone to Britain in March 1939 on a Kindertransport. He’d been a child refugee.

Over the years that followed, I was unable to find out more. This is ironic given that I had become a journalist, as had one of my sisters. Despite growing up in a household that forbade questions, we had both built our lives on careers that demanded we do so. However, it felt impossible to turn our journalistic skills towards our father. If my father had wanted me to know about his past, I reasoned, he would have told me. Out of respect I didn’t want to transgress his clear instruction not to know. I also felt frightened. What if he’d hidden his Jewish heritage to keep us safe in case it happened again? One of his most repeated historical quotes was George Santayana’s: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Maybe he deliberately buried his personal history to avoid it repeating for his daughters.

It was to be another twenty-five years before I had the courage to overcome that cocktail of fear and guilt. It was the British general election of 2015. I had turned from television journalism to politics, and was standing as a Green Party parliamentary candidate at the election. Antisemitism was on the rise. I didn’t feel I could talk publicly about the issue while hiding my own Jewish heritage, whatever that might mean. As I changed my biographical description to include my father’s heritage, I felt fear, but also a sense of liberation. It was as if I were beginning to reclaim one part of my family’s unknown past. The genie was out of the bottle. Now that I had “come out,” I wanted to know more.

By this point I had been through years of intense therapy, with various therapists suggesting I displayed the symptoms of someone suffering second-generation trauma. But trauma because of what? It wasn’t that mystery that bothered me so much as my never having had the chance to really “know” my father. That was coupled with what was, if anything, a still more painful fact: my father, who had overcome so much in his life (or at least the limited bits of his life I knew about), had died as emaciated and skeletal as those liberated from the concentration camps.

Parkinson’s disease had done what the Nazis had failed to. He had spent his final years incarcerated in a rundown nursing home, trapped in his own pain-ridden body, unable to speak and unable, most poignantly to me as a writer, to finish the book that he’d spent much of his life working on, alongside his editorship of History and Theory.

It left me feeling unbearably bleak and fed my own existential struggle with meaninglessness. That my father could have escaped the Holocaust to have died what felt like an equivalent death was unbearable. His book unfinished, he had failed to make his mark on the world. To top it all, my mother had decided, out of respect for his atheism, that he shouldn’t have a grave. So, there was literally nothing tangible left to mark his existence, not even somewhere to grieve. He had been erased.

Since standing for parliament, and despite being dogged by depression, I was doing anything but staying silent. In 2018, spurred on by pictures of refugees drowning at sea while trying to reach safety in Europe, I set up Compassion in Politics, an NGO that would campaign for a more compassionate response to human suffering. I was thrilled that the celebrated British parliamentarian Lord Alf Dubs, who had himself come to the Britain on a Kindertransport, agreed to be our patron.

I became more desperate to know about my father. I did what online research I could and discovered that, when he arrived in England as a fifteen-year-old in March 1939, he was alone. He’d spent a year living with a family in Midhurst in Sussex, before at sixteen being arrested, along with thousands of other refugees, many of them Jewish, as an “enemy alien.” In May 1941, Churchill had instructed British authorities to “collar the lot,” in other words to round up those with a German or an Austrian passport. My father went from being a child refugee at fifteen to an enemy at sixteen. He was interned in a camp on the Isle of Man and then deported on the prison ship the HMT Dunera.

A few years later, in 2019, I was invited to speak in Australia at a conference about compassion. It reawakened my old longing to connect with my father’s past. I couldn’t resist the idea that maybe there was someone still alive in Australia who had known him from his Dunera days. At the last minute, I looked online and found an article about the Dunera by a historian called Seumas Spark. I dropped him an email and caught my flight.

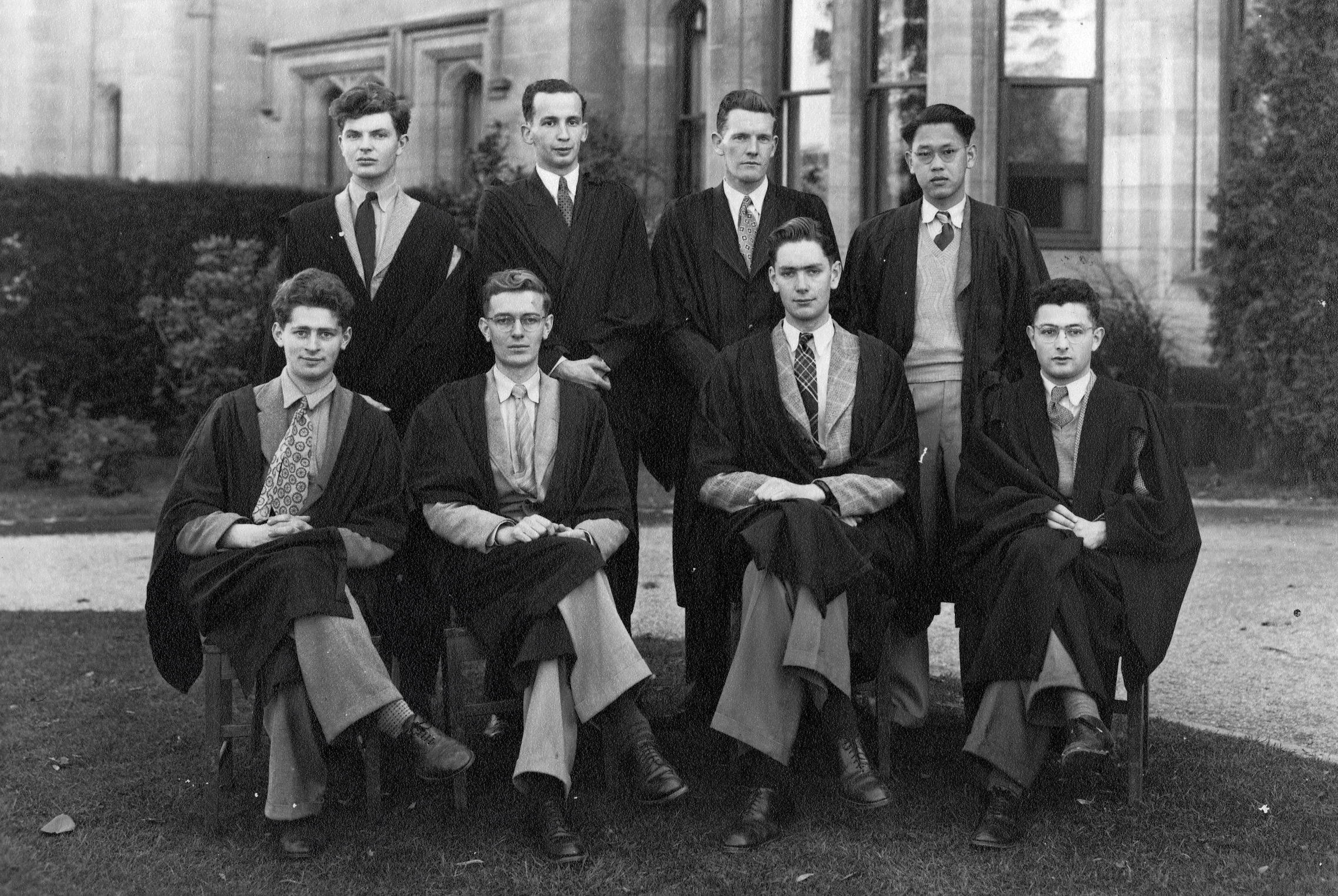

When I arrived in Melbourne, my host — in an attempt to keep me awake and stave off the jetlag — took me on a series of museum visits. The first stop was the Jewish Museum of Australia. I asked the curator if she had anything on the Dunera. She went to a bookshelf and retuned triumphantly with a large academic tome entitled Dunera Lives. There was a whole page of information about my father and a photo of him at Queen’s College, University of Melbourne. The author was the very same Seumas Spark whom I had emailed before leaving.

Seumas and I met the next day. Over coffee and Viennese cookies, he told me how excited he was to get my email. Working alongside the historian Ken Inglis and others, Seumas had devoted much time to researching the Dunera and the lives of the men it brought to Australia. “We’ve been looking for George’s descendants for a decade,” he explained, “but kept drawing blanks.” My father’s privacy had resulted in his having covered his tracks so well that even contacting History and Theory hadn’t yielded an address for Seumas to find us.

A friendship quickly developed. I learnt that when the men had finally arrived in Sydney, in September 1940, many emaciated and sick from months at sea, they were interned by the Australian government, as instructed by the British, in detention camps. Their mistreatment was eventually publicly acknowledged and, later, they became widely known in Australia as the “Dunera Boys.”

When Seumas came to England to research the artwork of another Dunera Boy, Georg Teltscher (George Adams), I went with him to meet George’s widow, Sara. From her I got a clear account of what life in the camp had been like: how the inmates, many of them intellectuals and artists, had organised themselves and created their own “university” within the camp, with lectures, seminars, art workshops and concerts. They’d put on plays and even designed and printed their own currency.

Sara also had her late husband’s collection of drawings and paintings from that time and so I was given a visual insight, too. I saw a clutch of huts, surrounded by barbed wire, in the middle of a barren and remote patch of Australia. Seumas took me on other Dunera-related expeditions in London too, including to the British Museum print rooms to see its collection of Dunera art. The night before Seumas left to go back to Australia he handed me a manila folder, similar to the ones I’d seen stacked on my father’s desk as a child. “This is all I have,” he said. “It’s our research file on your father.”

I left it on my desk for some months. Again, I was inhibited by the old feeling that I was breaking my father’s cardinal rule. When my curiosity finally got the better of me, I found a wealth of anecdotes and accolades about my father’s academic work, including the frequent observation that his work was continuing to have an influence on academic thinking to this day. After years of despair about my father’s wasted life, it turned out that he had left a very visible trace. His work continues to be researched, studied, discussed and built upon. And even more to the point, there was a historian actually researching his life and publishing papers that featured him.

However, while those interviewed by Seumas had much to say about my father’s professional life, there was nothing about his personal one. Indeed, many of them commented on the air of mystery that surrounded him. Because he had not been willing to talk about his background or personal affairs, rumours abounded. There were snide comments, which Seumas kindly attributed to professional jealousy, but which, to some extent, rang true to me from my childhood.

I had one other possible lead. The academic who had taken on the editorship of History and Theory was living in London. Full of fear and burdened by the knowledge that my father would have hated my making contact, I arranged to meet the former editor, Richard Vann. He and his wife invited me to tea in their Kensington flat.

They were familiar figures from my childhood, having visited us in Sussex regularly through the years. It was strange to re-meet them as an adult. Strange also to see them living and breathing so many years after my father had passed away. They had laid out a formal tea, perhaps remembering the formality with which they’d been treated whenever they visited us in Sussex.

Before I’d even had a chance to sit down, Dick burst out, “We are so glad you’ve come. Now you can tell us about your father.” Dick explained that although he’d worked with him for forty years, he knew nothing of his private life and family background. My hopes were dashed; the man I’d come to for answers had even more questions than I did. I’d drawn a very definite blank; at least I wasn’t the only one.

It was interesting how much came to be projected on to my father’s life in the absence of the normal biographical knowledge that most of us have about each other, especially in this digital age. A number of articles online said that he had married a Rockefeller. Not true. Another took a prank he had played at university and interpreted it as evidence of something untoward. My father had rigged up a dummy in his study to make it look as if he were working all night, when in fact he was out — I hope having a good time. This was lifted straight from Sherlock Holmes, but to the historian who wrote about my father it became something sinister.

I met an academic from Sydney who said he was fascinated by my father because of his “missing years.” “I could find nothing about him online from 1990 onwards,” he said. “I mean, what was he doing? Why did he just disappear?” I told him that he’d got a little overexcited. My father’s “disappearance” wasn’t due to some mysterious clandestine mission, but because he’d died.

My sisters and I may not have known about my father’s past, but we nevertheless absorbed its emotional impact, which has played out in our lives. Of his three daughters, two of us have suffered from severe depression, which started in our mid-teens (at about the age our father fled Vienna). This depression was accompanied by excessively high levels of fear and insecurity, and a belief that we “didn’t belong,” that we would get found out at any moment. We have both felt that we have spent our lives studying how to appear normal, endeavouring to do this or that, and often failing. We have felt there was something shameful about us, but what exactly we couldn’t quite identify.

I have lived with an excessive fear of impending catastrophe. In my twenties, I was fortunate to go out with a wonderful and kind young art dealer who worked for his father’s business. He had the sort of financial security most of us can only dream of; they had vaults of priceless artworks, including by the Italian painter Canaletto and well-known impressionists. The sale of any one of these could have provided comfortably for a lifetime, and yet I was riddled with fear that we weren’t secure enough.

I became preoccupied that he didn’t have a second career to fall back on: “What happens if we have to flee Britain and you have no more art?” I would beg him to qualify as a teacher so that he’d have a skill to his name, utterly unable to see the reality of his situation, or to see how my father’s unnamed experience was subconsciously driving my fear.

There are other coincidences. As a broadcast journalist, I devoted myself, both on television and in print, to the task of trying to free people who had been wrongly imprisoned. Again, I wonder if my father’s own story played out untold in my concerns. And in my children, too. My oldest son, who can be alarmingly like my father, has struggled with the same depression as my sister and me, beginning at roughly the same age that my father’s journey began.

Another coincidence that amuses me is that my journalist sister chose a decade or so ago to get a house in the country. She chose to live in a beautiful town called Midhurst, the very same Sussex town, it transpired, where my father had found initial safety when he fled Austria.

I can hear my father’s voice dismissing these “coincidences” as unscientific but, for me, perhaps one of the biggest pieces of experiential proof I have of their truth is this: over the recent past, since I began to reclaim my father’s story, my own depression has abated. I have gained an increased sense of comfort. A sense that it is okay to be me and that I no longer have to pretend or work hard to camouflage myself to fit into everyday society. By bringing the unknown from my subconscious into my conscious, a real and liberating shift has occurred.

Despite the healing I have found, however, a deeper political concern continues to trouble me. If my father were fleeing persecution now and trying to reach Britain, I doubt he would be permitted entry. The dogwhistle racism in Britain ushered in by Brexit, the brutality of Trump, and a British government that thought deporting traumatised refugees to Rwanda was decent policy spell a dangerous shift in attitudes towards refugees, in Europe, Australia and across the globe.

Our collective memories are short. And individualistic neo-liberal ideologies have left too many of us divorced from the values that create a caring, cohesive society. As mass migration brought about by climate catastrophe threatens to dwarf the current global refugee crisis, we are at a dangerous point. War has flared once again in Europe, and the Middle East is ablaze.

I find myself in my political work haunted by the quotes my father had me transcribe as a child; often I use them in speeches. Increasingly it feels that “mere anarchy” is being “loosed upon the world” and that the “odds” are indeed “gone.”

As I look out across today’s bleak political landscape, with its rising levels of hate and its failure to prevent injustice, I remember my father’s preoccupation with Santayana’s remark, which now seems more prescient than ever. My hope is that we will remember and learn from the history of the last century before it’s too late, so that we and the generations to come are not doomed to relive it. •

This is an extract from Fault Lines: Australia’s Unequal Past, edited by Seumas Spark and Christina Twomey, published this week by Monash University Publishing.