Near the old Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney a stark slab of wall, angled outward from a glass background, houses a table and a leaning potato-digging spade known as a loy. The glass panels behind it are etched with the names of the “Orphan Girls,” four thousand of whom were sent to Australia in the 1840s.

This is the Irish Famine Memorial, unveiled in 1999 as part of a late-twentieth-century wave of Famine monuments erected by Irish communities around the world. What distinguishes this memorial from many abroad (particularly in the United States) is its restraint — its refusal of pathos and spectacle. South in Williamstown, west of Melbourne, a bluestone outcrop known as Famine Rock bears a plaque to the million who died in Ireland and the tens of thousands who emigrated to Hobson’s Bay. Between them, these monuments signal how a calamity half a world away became part of Australia’s own European story.

Padraic X. Scanlan’s Rot: A History of the Irish Famine returns with moral and intellectual force to a catastrophe whose afterlives ripple across oceans, institutions and memory. His narrative is less a chronicle of blight than a diagnosis of political disease: the lethal fusion of colonial governance and ideological market logic that transformed crop failure into mass starvation. Reading him from an Australian vantage, one is struck as much by the power of his indictment as by what it leaves implicit — the Famine’s global currents, the moral limits of nineteenth-century states, and the way memory has been shaped less by suffering itself than by what later generations can, or choose to, remember.

Rot is neither academic history nor polemic but a moral narrative grounded in vivid archival fragments and lucid anger. Scanlan writes against the consoling myths — the idea that the Famine was a tragic accident, for example, or that relief efforts were earnest if inadequate — that once softened British culpability. Instead, he frames the Famine as an exposure of the empire’s governing faith in progress: a system that rendered whole populations expendable in the pursuit of moral and economic order. His prose has the clipped urgency of someone writing against evasion; his sentences sting because they are composed with the calm precision of a historian who knows the evidence and has the restraint to let it speak.

Scanlan’s book stands at an interesting crossroads in the literature on the Irish Famine. It revives the moral passion that mid-twentieth-century revisionism had sought to drain from Irish historiography. For historians such as T.W. Moody and R. Dudley Edwards (and later Roy Foster), professional detachment was the necessary antidote to nationalist grievance. Cecil Woodham-Smith’s The Great Hunger (1962) broke that decorum, restoring outrage and narrative immediacy to a history long buried under administrative prose. Like Woodham-Smith — whose indictment of British policy struck a nerve as the Troubles began to stir — Scanlan writes with ethical intensity and narrative verve, making the Famine legible to the general reader without recourse to models or statistics.

Both insist that famine was not fate but policy: a catastrophe wrought by the cold conjunction of ideology and administration. Where Woodham-Smith sought to expose the culpability of a generation of officials, Scanlan widens the frame to the system itself: the twin logics of colonial hierarchy and market rationality. His ambition links Rot to his earlier Slave Empire: How Slavery Made Modern Britain (2020), which traced another form of coerced dependence beneath the rhetoric of liberty. Both books show how Britain’s ideals of freedom and improvement were sustained by systemic unfreedom, and how moral blindness can be structural rather than personal.

Historians such as Christine Kinealy and Peter Gray have since combined empathy with analytic depth, producing accounts more humane and textured than the detached empiricism of their revisionist predecessors. Kinealy’s This Great Calamity (1994) and Gray’s The Irish Famine (1995) resist the older impulse to neutralise outrage, even as they reconstruct the bureaucratic machinery of relief. Gray, in particular, situates laissez-faire within the wider intellectual climate of the 1840s while recognising its moral bankruptcy in practice. Scanlan builds on this moral turn but pushes it outward from the island to the imperial and global.

Few serious historians today would describe the Famine as an act of deliberate genocide, though the accusation — first levelled by the transported nationalist John Mitchel (erstwhile denizen of Van Diemen’s land) and echoed by his successors — retains considerable political potency. Mitchel’s fiery handle that “the Almighty sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine” captured the outrage of his age and survives as slogan.

Scanlan’s villain is not England as such but the moral complacency and barbarity of empire and its systemic exclusions. In his account, the Famine becomes the moral x-ray of an imperial age. The problem was not simply that the potato failed, but that the imagination of the governing class failed with it. In a world where markets were treated as natural forces and providence as a form of economic law, starvation could be rationalised as self-correction.

Rot traces this reasoning with controlled fury, from the notorious memoranda of Charles Trevelyan, the Treasury official who oversaw relief and believed the Famine was “a direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful Providence,” to the pseudoscience of “moral improvement.” The book’s power lies in this moral lucidity, its refusal to hide behind context or bureaucratic complexity.

And yet context, including international, still matters. The Famine was both an Irish catastrophe and a European one; both a failure of policy and a symptom of mid-Victorian limits.

It remains plausible to call it the greatest humanitarian disaster of nineteenth-century Europe, at least in proportional terms: a million dead, another million forced abroad, a national population halved within a generation and an ancient culture eviscerated. But it was also the product of an age that had no state apparatus for social welfare, no coherent theory of public obligation beyond the Poor Law, and no intellectual vocabulary for systemic compassion. To demand that the British government in the 1840s act like a modern welfare state — or to imagine it could have viewed Ireland in anti-imperial terms — is to risk a different kind of distortion: one born of moral hindsight.

Judged by the standards of its own time, Britain’s response was neither uniquely callous nor straightforwardly benevolent. What distinguished it was the moral grammar through which relief and restraint were justified. The doctrine of laissez-faire, as Scanlan shows, was less an economic policy than a theology: suffering was productive, scarcity disciplinary, charity corrupting. Yet to see the Famine purely as a triumph of market dogma over mercy misses how those markets were already profoundly constricted. The poor were not destroyed by the operation of capitalism so much as by their exclusion from it.

As Amartya Sen would later observe, no substantial famine has ever occurred in a functioning democracy with a free press. Ireland lacked not only food and representation but the political mechanisms through which suffering might have compelled a response. Famine, in this view, is never merely natural or economic but rather the ultimate failure of civic inclusion. The Irish were not simply the victims of markets: they had no purchasing power, no legal security, no stake in the system said to govern them.

In that sense, the Famine was a catastrophe of non-participation as much as of ideology. As the twentieth century would show, other ideological fixities and compromised democracies — those of communism and state-controlled economies — could also result in horrific mass starvation.

In comparative perspective, Britain’s policies in Ireland were appalling but not unique in their logic. During the roughly contemporaneous Highland famine of the 1840s — much less devastating than the Irish experience — Scottish crofters were largely abandoned to the ministrations of landlords and charitable committees; when relief came, it was often tied to assisted emigration. Three decades later, in the Indian famine of 1876–78, the Raj’s administrators repeated the mistakes made in Ireland, imposing relief wages so meagre that labourers expended more calories than they could consume, producing vast mortality.

The difference is one of degree, not of kind: the same utilitarian fear of dependency, the same faith that discipline and scarcity would ultimately do good, the same sense that from catastrophe a new modernity might emerge.

If Ireland’s tragedy feels distinctive, it is because of its proximity to the heart of empire. It was the empire’s own back garden, and its failure there could not be exported or denied. It is also because the Irish diaspora that spread around the world as a result accrued enough power and influence to narrate its own catastrophe. Unlike India’s victims, Irish emigrants and their descendants belonged to the empire’s white European family: their suffering could be assimilated into imperial conscience rather than written off as the cost of dominion.

Seen from that angle, Britain’s failings in the 1840s were not merely moral but epistemic: an inability to imagine the Irish poor as citizens of the same moral universe. Yet to treat this as a peculiarly British pathology is too simple. Most European states of the mid-nineteenth century lacked a coherent language of public responsibility. France and Belgium responded to poor harvests with export bans and ad hoc municipal relief; the Russian empire tolerated recurrent regional famines that killed hundreds of thousands. What made Ireland different was the relative scale of the calamity, its intimacy with the imperial centre, and the ideological embarrassment it caused, a humanitarian failure within a polity that prided itself on civilisation.

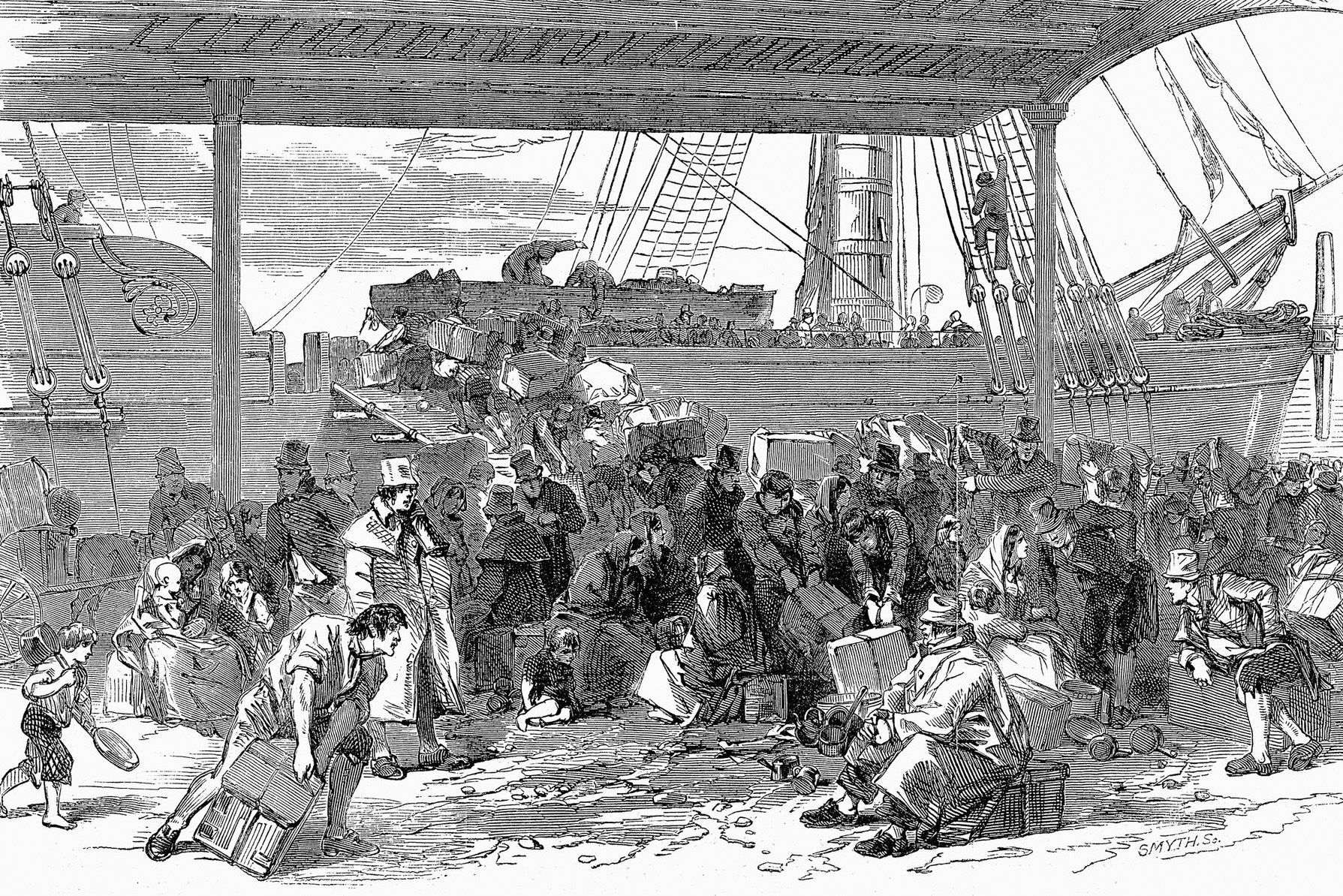

The Famine’s reach extended far beyond Ireland’s shores. Its human debris helped populate the empire it condemned. Between 1848 and 1850, around four thousand young women — the “Orphan Girls,” mostly teenagers from Irish workhouses — were sent to Sydney, Port Phillip and Adelaide under the Earl Grey scheme. Officially, this was a humanitarian measure, rescuing them from destitution and offering new lives as domestic servants. Unofficially, they were a social experiment in transplantation, designed to redress the gender imbalance of white settlement.

Met with sectarian and anti-Irish disdain and hostility in some quarters, the young women were absorbed into colonial households and, eventually, colonial lineages. Their descendants include premiers, writers, schoolteachers and police commissioners. The program, harsh as it was, bound the catastrophe of Irish destitution to the project of settler expansion, giving the Famine an afterlife inscribed in Australian demography.

Relief also flowed in the other direction. In 1847, public subscriptions in New South Wales raised about £5000 for Irish relief, a sum impressive for a small colony. Melbourne and Adelaide held their own fundraising drives, while Irish migrants in Van Diemen’s Land sent money and goods through church networks. These gestures of solidarity, modest in scale, reflected not only humanitarian feeling but also a wish to remain connected to the homeland. If the Famine revealed the brittleness of imperial benevolence, it also generated a new form of diasporic responsibility: the belief that the Irish abroad might redeem what Britain had destroyed.

The emigrants’ dispersal turned Ireland’s local catastrophe into a global moral narrative. Across the nineteenth century, survivors and their children carried its memory into the politics of their adopted lands: into the urban Catholicism of New York, the agrarian radicalism of the American Midwest, the sectarian divides of colonial Australia that endured until the 1970s. They transformed private grief into public identity.

Yet that identity was unequally legible within empire. The Irish poor could be sentimentalised in ways Indian peasants could not. Whiteness and Christianity offered entry into imperial compassion, a seat at the table of shared suffering. The Famine became mournable because its victims could be imagined as kin.

Scanlan, to his credit, is alert to these diasporic currents. Rot ranges far beyond the parochial history of landlordism or poor relief to trace how the Famine shaped global capitalism, how migration, remittance and memory fed back into the moral economy of empire. Yet his canvas, for all its breadth, remains largely Atlantic, admittedly the major destination of Famine refugees, along with Britain. Australia appears only glancingly, as a distant beneficiary of Britain’s “surplus” poor. That absence is symptomatic of a wider pattern in Famine historiography: a tendency to treat the Irish diaspora as a transatlantic phenomenon, overlooking the colonial peripheries that absorbed its displaced.

Reading from here, one feels the gap keenly. The Famine orphans who arrived in Sydney and Port Phillip were as much imperial exports as the convict labour that preceded them. They remind us that Famine relief and settler colonisation were twin projects — one humanised the empire, the other extended it.

What Rot captures superbly is the texture of bureaucratic cruelty: the memoranda, the statistical abstractions, the polite horror of officials confronted with human ruin. At times, however, Scanlan’s insistence on ideology — the idea that capitalism and colonialism explain the catastrophe — risks flattening the very complexity he evokes. We must also recognise the strictures of a past that formed those blinkered men who thought themselves rational, or the bureaucrats who confused obedience with duty, if we are to recognise our own systemic strictures.

That tension — between moral clarity and historical pity — has defined much of the Famine’s representation since. One of the challenges for any writer on the Famine is that the event overwhelms expression. It resists adequate representation. A million deaths, another million exiled, villages emptied, language lost. The apocalypse behind these figures defies conceptualisation. The writers and artists who have tried to convey it, from William Carleton to Seamus Heaney, have stumbled on the same problem: famine leaves a silence at its centre. Scanlan acknowledges this difficulty obliquely, through the spareness of his style. His sentences refuse ornament, as if wary that beauty itself might be indecent. In that restraint lies part of the book’s power.

The proliferation of Famine memorials in the 1990s — Sydney, Williamstown, Boston, New York, Toronto — reflects both the endurance of that silence and our need to fill it. Their language of commemoration borrows from the idiom of trauma, a discourse that came to prominence in those same years. Suffering became a credential of belonging; historical wounds a means of claiming moral visibility.

In the United States, Irish-American organisations campaigned to have the Famine taught alongside the Holocaust, sometimes invoking the language of genocide to assert parity of pain. In Australia, the monuments are quieter, more ambivalent, conscious perhaps that Irish tragedy unfolded on land already scarred by another dispossession. The Williamstown plaque, unusually, acknowledges both the Famine dead and the First Nations peoples displaced by colonial expansion — a rare memorial willing to admit that victims can also be colonial settlers.

Rot arrives, then, at a moment when the Famine has moved from nationalist grievance to global parable. Scanlan’s book invites us to see in the Irish catastrophe a pattern that recurs whenever ideology outruns empathy — whether in the Raj of the 1870s or in the austerities and food insecurities of our own century. If the lesson sometimes feels overstated, that is because it bears repeating. The moral question the Famine posed — how societies rationalise suffering in the name of order — remains unsolved.

Reading Rot from Australia sharpens that question. The Famine’s emigrants helped build the settler colonies whose prosperity rested on other forms of dispossession. The Irish poor were both victims and beneficiaries of empire. Their hunger propelled them into lands where others would be made hungry. Scanlan hints at this contradiction but leaves it largely unexplored. It is a reminder that moral history, too, has its blind spots.

No single book can capture the totality of the Great Famine. Its horror exceeds comprehension; its meanings shift with each generation. What Rot offers is not closure but clarity: a narrative that restores urgency to an event too often neutralised by statistics or sentimentality. If Scanlan writes with anger, it is an anger earned by evidence.

Yet the Famine’s truth finally lies beyond ideology — in the stubborn fact of human suffering and in the inadequacy of any system, economic or moral, that seeks to justify it. Near the Hyde Park Barracks, that angled table and empty shelf of potatoes remain: a reminder that memory is at its most eloquent when it declines to console. •

Rot: A History of the Irish Famine

By Padraic X. Scanlan | Robinson | $34.99 | 349 pages