For the shrinking fraction of the public that is even dimly aware of it, the image of psychoanalysis tends to be tarnished. Some of the lost lustre is the patina of age, the movement often viewed as a relic of the early twentieth century. Some of it comes from bruising encounters with philosophers of science and psychologists, and some from the rise of alternative approaches to treatment in the mental health industry. And a share of the disenchantment is self-inflicted, the result of dogmatism and cultishness.

Psychoanalysis is more alive than it might seem, but psychoanalytic writing can continue to frustrate those who are not full-blown believers. Too often it is opaque, over-confident or contrary — everything is the opposite of what it seems — and inordinately fond of aphorisms. It’s rare to find writers who express the analytic sensibility in ways that are open-minded, plain and humble, that reach for the truth of human experience instead of proclaiming it. Those who do this well tend to be clinicians rather than theorists, or at least clinicians who confine theory to their footnotes.

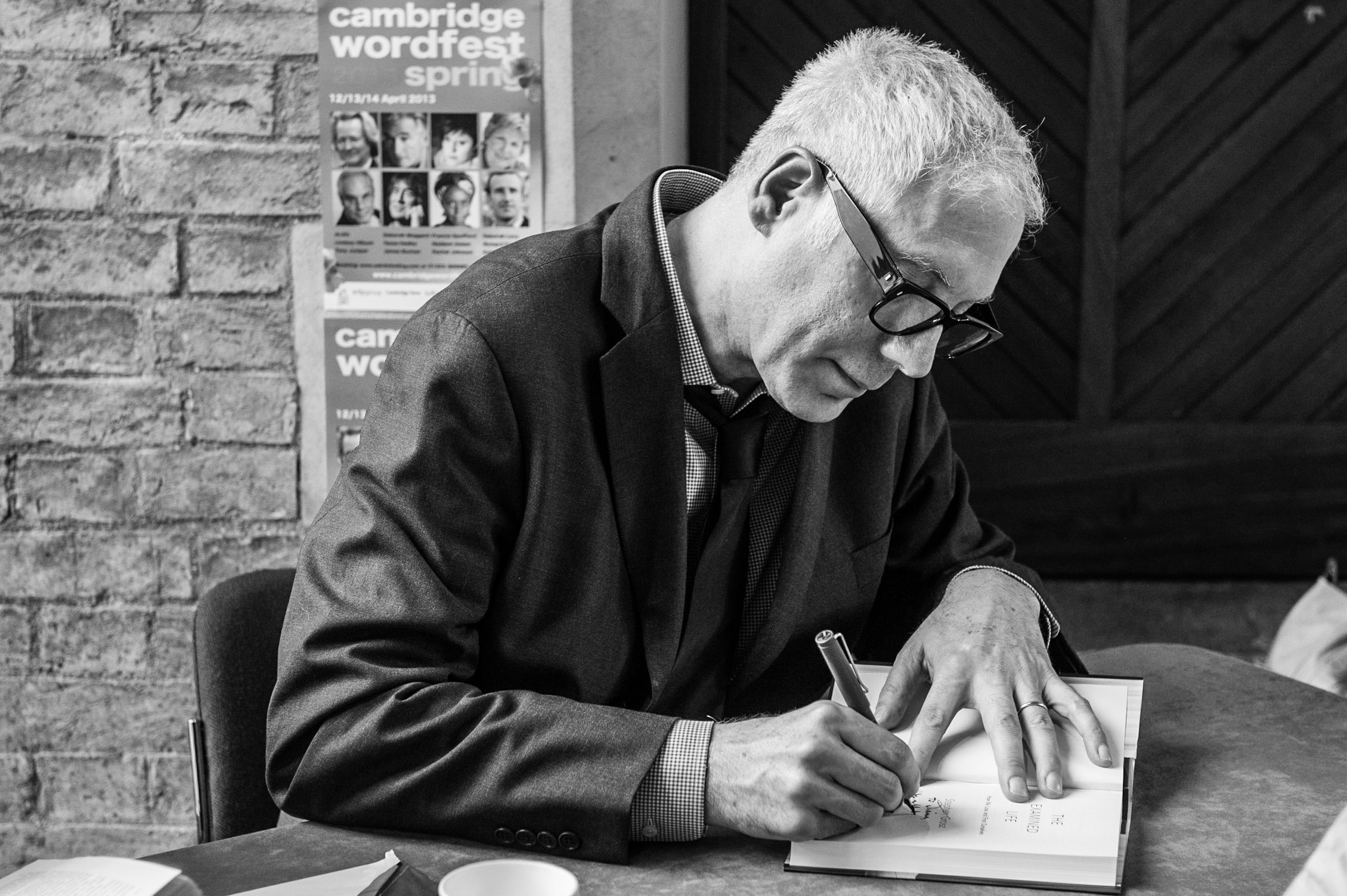

Stephen Grosz is a supreme exponent of this kind of analytic writing. His The Examined Life was a bestselling collection of case stories drawn from his clinical practice. His new book, Love’s Labor, offers a new collection of cases that explore the challenges of intimacy. We encounter people unsure of whether to marry or divorce, a man tormented by delusional jealousy, women who engage in sex work or enter disastrous relationships in ways that reveal the abuses and entanglements of their early family lives.

Others struggle to overcome romantic loss, avoid love because it will end, or resolve its challenges by conducting a shadowy sex life in parallel with a conventional marriage. One analyst has an affair with another’s husband, the viciousness of their fight — “using psychoanalytic concepts as sword and shield” — confirming my impression that mental health professionals have the nastiest arguments. The final story, “Hauntings,” is the most moving and memorable case study I have read.

Grosz’s general approach is to interweave reconstructed conversations from therapy sessions with reflections on the persistence of beliefs and desires forged in early life. “To be human is to be uncertain, conflicted, divided” and our beliefs about ourselves often stand in the way of resolving our difficulties. “The greatest obstacle to learning about ourselves isn’t ignorance,” he argues, “but our ‘self-knowledge.’” Love’s labour — “the work we must do to see clearly ourselves and our loved ones” — is challenging work, and a good analyst can lighten the load.

In Freud’s time, analysts tended to absent themselves from their case studies just as they were instructed to serve as neutral “blank screens” in the analysis itself. His early cases read like detective fictions: the analyst cracks the case by deciphering psychic clues and acts more as a sleuth than as the patient’s accomplice. Grosz’s approach is very different. His cases come to life thanks to his skill in conveying the immediacy of the therapeutic process and his role as engaged participant rather than aloof observer.

Indeed, one of the finest things about this book is how generously Grosz opens himself up to view. The reader learns about his path to becoming an analyst, the importance of his supervisors, and some pivotal experiences in his life, from a meeting with Anna Freud to his mother’s death. He maintains that analysis is a joint process of discovery in which his understanding of the patient slowly evolves and is always provisional. Months are spent trying to figure out why one patient is always fifteen minutes late for her sessions, many interpretations emerging only to fail to break the pattern until a moment of insight.

“Psychoanalysis has its own predictable narratives,” Grosz writes, “but when done properly, it does not provide ready answers. Instead, it offers a place where two people can be ruthlessly honest, think together, find meaning together.”

This is primarily a book of people and stories rather than ideas, but Grosz offers some intriguing thoughts on what psychoanalysis is for. Is it all about gaining self-mastery (“where Id was there shall Ego be,” as Freud wrote) or personal liberation? Living without illusions or functioning well in society? Freedom from repression or from impulse? Grosz lists twenty alternative aims proposed by psychoanalytic heavyweights, demonstrating how the enterprise of psychotherapy is complex and differs in important ways from other modes of treatment.

Without picking winners, Grosz suggests that “therapeutic zeal,” the desire to help, is an aspiration that can limit patients’ autonomy. Aiming to understand the patient may be more important than aiming to help them, a message that rejects the contemporary enthusiasm for quick psychological fixes. Love’s Labour is a compelling demonstration of the importance of understanding, and of the gradual, intersubjective process that produces it. •

Love’s Labour

By Stephen Grosz | Chatto & Windus | $36.99 | 208 pages