Many of us will always look back on mid March 2020 as a time of worry and confusion. As images of the pandemic’s international toll flashed onto our screens, state and territory leaders and prime minister Scott Morrison volleyed conflicting advice, especially about school closures. The tensions inherent in the Australian federation — that brave effort to accommodate a bickering family of states and territories — were being worked through with an urgency that could only result from a fear of mass death.

Australia was not alone. When Democratic governors imposed lockdowns in the United States, Donald Trump cried mutiny. Member states of the European Union closed borders with other member states, and Italy received medical supplies from China well before fellow Europeans reached out.

Amid this grinding of gears, it’s easy to forget that federation was once a Romantic ideal, not least among those many advocates of the Australian national project who campaigned during the closing decades of the nineteenth century for the entity that would be born on 1 January 1901. Inspired by nationalist movements in Europe and North America — including the unification of Italy — many politicians, writers and influential colonial figures saw the federal system as a step on the pathway to what they called global “brotherhood.”

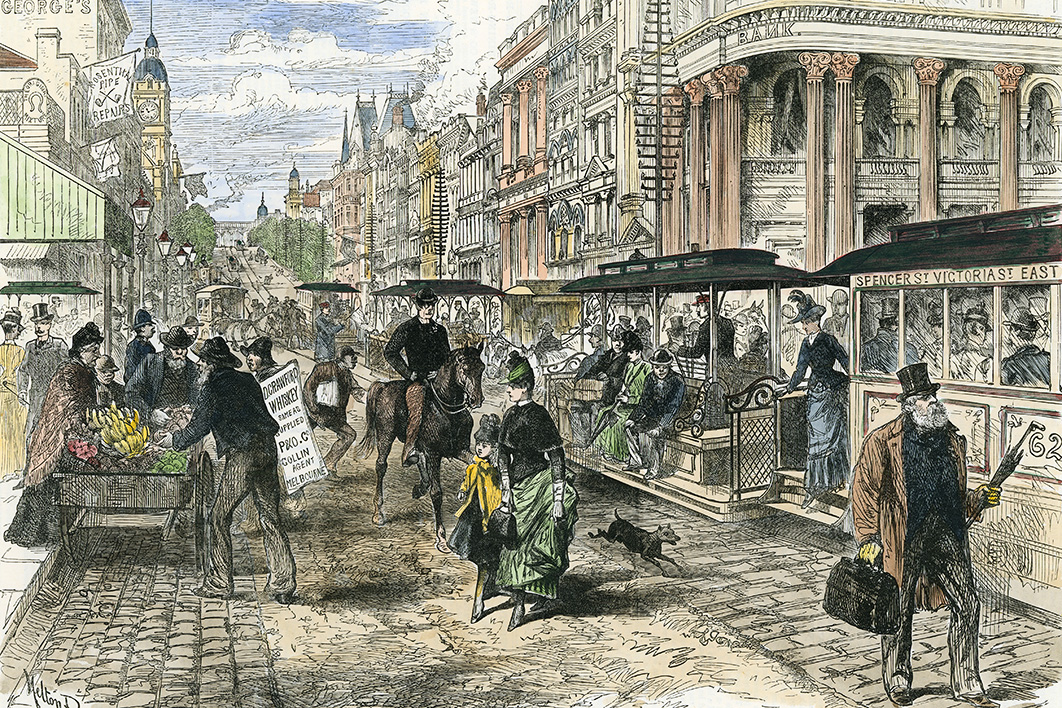

Nowhere do these earnest exhortations for federation resonate more fancifully than in the novel Melbourne and Mars: My Mysterious Life on Two Planets, which has been reissued this month by Grattan Street Press. Penned in the late 1880s by the English phrenologist and health reformer Joseph Fraser, this work of proto–science fiction stands out amid the countless flowery poems, hymns and essays that garnished the consensus-seeking mechanics of the federation process.

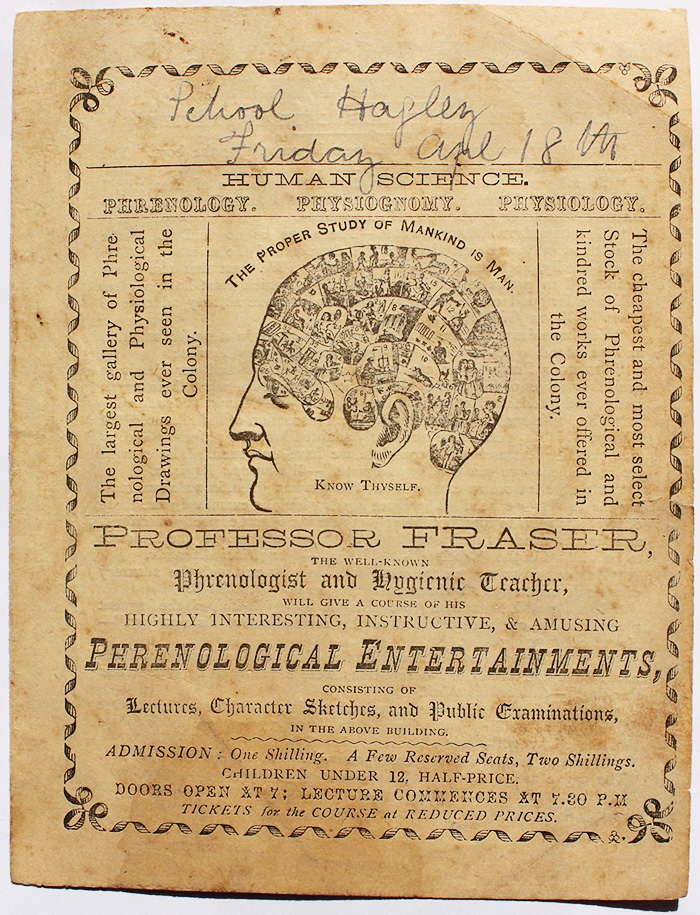

Character readings: A handbill for a lecture delivered by Joseph Fraser in regional Tasmania in 1884.

Enthralled by the Martian moment in popular astronomy, Fraser contributed to what late historian John Hirst termed Australian Federation’s “festival of poetry” by contrasting the grimy bustle of the metropolis of Melbourne with an attractively harmonious society on Mars. In Fraser’s utopia, a “Grand Federal Government” fosters progressive goals of gender equality among “Martials,” scientific innovation provides bountiful crops to sustain happy, health human life, and the state provides all material needs. This kind of federation, at its best, guarantees world peace.

In tone, the whimsical Melbourne and Mars rubs against our own experiences of day-to-day politics. The Ballad of Gladys, Dan and Scomo could not play out on Mars. But as our federation recalibrates in the wake of Covid-19, not least through new bodies such as the national cabinet, the novel provides a window through which to understand the ideas and dreams that created the Commonwealth of Australia more than a century ago.

Federalism’s tidal forces

From the early colonial period in New South Wales, Europeans born in Australia expressed a sense of a unique identity forged by their place on the globe. These “currency lads and lasses,” as they were known, many of whom were children of convicts, came to embrace a hardy British–Australian identity as “natives,” a term that wiped away the claims to land of Indigenous Australians.

By the 1880s, the idea of creating a whole from the patchwork of dynamic political entities (most famously promoted by New South Wales colonial secretary and premier Henry Parkes) had gathered force, driven in part by economic issues such as intercolonial tariffs. With French and German powers staking claims in the Pacific, the Federal Council of Australasia (made up of Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, Tasmania and Fiji) formed in 1885 to engage collectively with Pacific affairs.

The federation effort spanned the rest of the century. By turns, it included the Federal Council, constitutional conventions with popularly elected representatives, and a series of referendums at century’s end. It all culminated in the British Act of Parliament of 1900 that delivered the Australian Constitution. The imagined federation contained moving pieces: New South Wales was not always in, Fiji dropped out of the Federal Council, Western Australia flirted with separation, and the possibility of New Zealand’s entry remains in our Constitution to this day.

One of the chief visionaries of Australian Federation, journalist and politician Alfred Deakin, argued that democratic mechanisms should drive it, rather than diplomacy. Popular movements such as the many local federation leagues responded to what he termed “social forces”: “sentiment fired to enthusiasm; patriotism fused into passionate aspiration for nationhood; imagination quickening, and worshipping a high ideal.”

One person who drifted within what Deakin described as the “tidal forces of Federalism” during the 1880s was the popular scientific lecturer Joseph Fraser, who lived and wrote in the Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn. Born in industrial northern England around 1845, Fraser began lecturing in New Zealand in the late 1870s with his wife Annie Fraser, and by 1884 was living in southeastern Australia. He earned a living through phrenology — the science of reading character and intellect from head shape. Contested from its invention at the turn of the nineteenth century, this new science nevertheless captured the popular imagination, including as a form of self-improvement.

Fraser’s travelling life saw him tackling subjects ranging from child rearing to partner selection (complete with onstage “marriages”). In quieter moments, he scribbled about the relationship between science and religion, contributed pen portraits of political figures to Melbourne’s Herald, and issued charts to clients declaring the strengths and weaknesses of their grey matter.

The Frasers joined a milieu of progressive thinkers who experimented with the possibilities of both the material and the metaphysical worlds. Annie lectured on women’s health and conducted business as a hydropathist; Joseph issued helpful pamphlets, including Husbands: How to Select Them, How to Manage Them, How to Keep Them (with twenty-one illustrations). But his most lasting contribution is a work of fiction that distilled his eclectic philosophy — a final, optimistic love letter penned as he battled tuberculosis.

Miniature Martial histories

Published in 1889, Melbourne and Mars appeared at a time when the Red Planet was the canvas for bold imaginings. Partly, this was the result of Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli’s 1877 observation of “canals” on Mars, which were soon reimagined as systems of irrigation and therefore as signs of intelligent life.

The novel follows the story of colonial merchant Adam Jacobs, a happily married middle-aged British transplant who not only lives in the powerhouse city of the Australian colonies but, by a division of the soul, also resides on Mars in the body of a bright boy named Charles Frankston.

Through Jacobs’s diary, Fraser guides us into an ideal society of beautiful, four-foot-tall Martials as perceived by Frankston. Scientific innovation and wide-eyed self-improvement shape this idyll of flying ships and state provision, the Martials embodying altruistic socialism. Their political philosophy promotes moral education to cure social inequalities, and its non-revolutionary approach appeals to middle-class mores. Frankston earns global fame with a major breakthrough: a method for cultivating massive vegetables in the snow line.

“Perpetual Peace”: a lantern slide depicting a globe of Mars, c.1900–1940. State Library of Victoria

By contrast with Mars, the streets of Fraser’s Melbourne roar with “grinding wheels, clanging bells, discordant and angry voices.” The buildings tower in a dark cluster over pushing, hurrying people whose faces are “stern, hard, selfish, smileless, sickly, pale, wrinkled, careworn” and “ugly as with sinful passion.” This is a bleak world of competition and capital, emblematic of common moral anxieties about the metropolis.

Fraser explains that a Grand Federal Government rules Mars in a state of “Perpetual Peace.” But that was not always so, for this near-utopian state evolved from an earlier time of warfare between nations. Only when the “world grew sick of war,” and only when the towering city-state of Sidonia rose to such power that it could guarantee global stability, did the Federal Council of Ambassadors of nations settle on peaceful governance through a Central Executive. Thanks to this state of peace, the collective workers of the Martial federation could transform “waste” spaces (uncultivated land) into controlled and productive land. “Which nation will attempt to make Sahara into a sea, while its possession might have to be fought for by several European powers?” muses the narrator.

These miniature Martial histories of governance obviously sprang from the ideologies of the federation movement. Fraser arrived in Australia just as the Federal Council of Australasia took shape, and he embraced popular ideas of national formation as a pathway to human progress. The Melbourne of Fraser’s novel contrasts with the advanced inhabitants of Mars, who have passed through the stages of “race life” rather as a child grows into adulthood. For Martials like Frankston, who live on both planets, Mars — which is at least a millennium more advanced than Earth — serves as a “promotion.”

This model of progress through federation reflects the philosophy of the influential Italian politician and philosopher Giuseppe Mazzini. Born in 1805 in Genoa, Mazzini’s publications and Young Italy movement fuelled Italian unification, and that event captured the popular imagination in colonial Australia, where the patriot general Giuseppe Garibaldi also became a lauded hero.

Mazzini argued that the formation of nations — each built from a shared mission — would ultimately lead to a global union. Drawing on philosophers such as Immanuel Kant (Fraser’s “Perpetual Peace” draws directly on the 1795 essay of this title by Kant), Mazzini’s works influenced nationalist movements around the world and thinkers including Deakin.

The optimism of world federation radiated most brightly from Cole’s Book Arcade in inner Melbourne. Here, the whiskery bookseller and businessman Edward William Cole — beloved publisher of light works including Cole’s Funny Picture Book — fostered this utopian ideal, issuing tokens with cosmopolitan messages. “Let the world be your country and to do good be your religion,” proclaimed one of these shiny “Federation of the World” medals (many of which are now in the collection of Museums Victoria).

Whether Cole and Fraser exchanged ideas in person is unknown, although we can gauge Cole’s enthusiasm for the novel from his publication of an edition of Melbourne and Mars. In early 1890, just months after Fraser’s death from tuberculosis, Cole also announced an essay competition, offering prizes for the best works that argued the case for and against global federation.

Cole’s was a cosmopolitan spirit, and his openness towards Asia conflicted with popularly held desires for a white Australia.

Deakin — the idealistic booster of federation — believed in a pure racial destiny for this nation-continent. He was part of the government that drafted the Immigration Restriction Bill (passed by the new parliament in 1901) that created the infamous dictation test by which Australian border officials could deny entry to migrants if they failed a test in any European language. The bill built on decades of anti-Chinese sentiment and formed part of the tapestry of the White Australia policy, which also enabled the deportation of Pacific Island labourers from Queensland.

This underbelly of exclusion also lurks in Fraser’s book. While Fraser did not present explicitly racist views in Melbourne and Mars, in his colonialist depiction of New South Wales, Indigenous characters figure only as two-dimensional plot devices. Meanwhile, his Martials answer solely to Anglo-Saxon names. And places such as Port Granby and Mount Weston expand to intergalactic proportions the widespread project of European mapping.

Between utopia and dystopia

Fraser’s book received a handful of reviews in late 1889, with the Melbourne Herald proclaiming that “no one who reads the first half-dozen pages is likely to put the book down until the last sentence is reached.” But other traces of its reception evade us. Its slipping below the surface of Melbourne life must partly derive from Fraser’s death in January 1890, just weeks after the book’s publication.

In our own time, as the tectonic plates of geopolitics and our own societies realign, the hopeful, surprising pages of Melbourne and Mars remind us that, even at its most compelling, any vision for the future is still just one of many possibilities. The world did not unite in a grand altruistic government, as Fraser hoped. And Australian Federation could not completely resolve the competing needs and whims of its parts, as evidenced in Western Australia’s unsuccessful attempt to decouple in 1933. The practicalities of our federal system weave through many issues — from revenue raising, to marriage, to waterway management in the midst of climate crisis.

For now at least, the tensions that glared from our televisions in March have subsided thanks to the stability afforded by Australia’s relative success in limiting Covid-19 transmission. But as the Black Lives Matter protests held across Australia remind us, we also face a greater challenge: overturning the very compact of whiteness on which this nation rests. We must confront dystopia. Remedying Australia’s founding flaw of dispossession and racial exclusion will require a radical work of reimagining, an act of dreaming and collective will worthy of this little patch of Planet Earth. •

Melbourne and Mars: My Mysterious Life on Two Planets by Joseph Fraser, edited and with an introduction by Alexandra Roginski and Zachary Kendal, is available from Grattan Street Press.

Funding for this article from the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund is gratefully acknowledged.