You’d be forgiven for thinking we don’t need another book about Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell. From Ghislaine Maxwell: The Making of a Monster to Hunting Ghislaine to The Spider: Inside the Cruel Web of Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell (among many others) a small publishing industry has sprung up to guide us into their shadowlands of entitlement and exploitation. I never felt I needed to return.

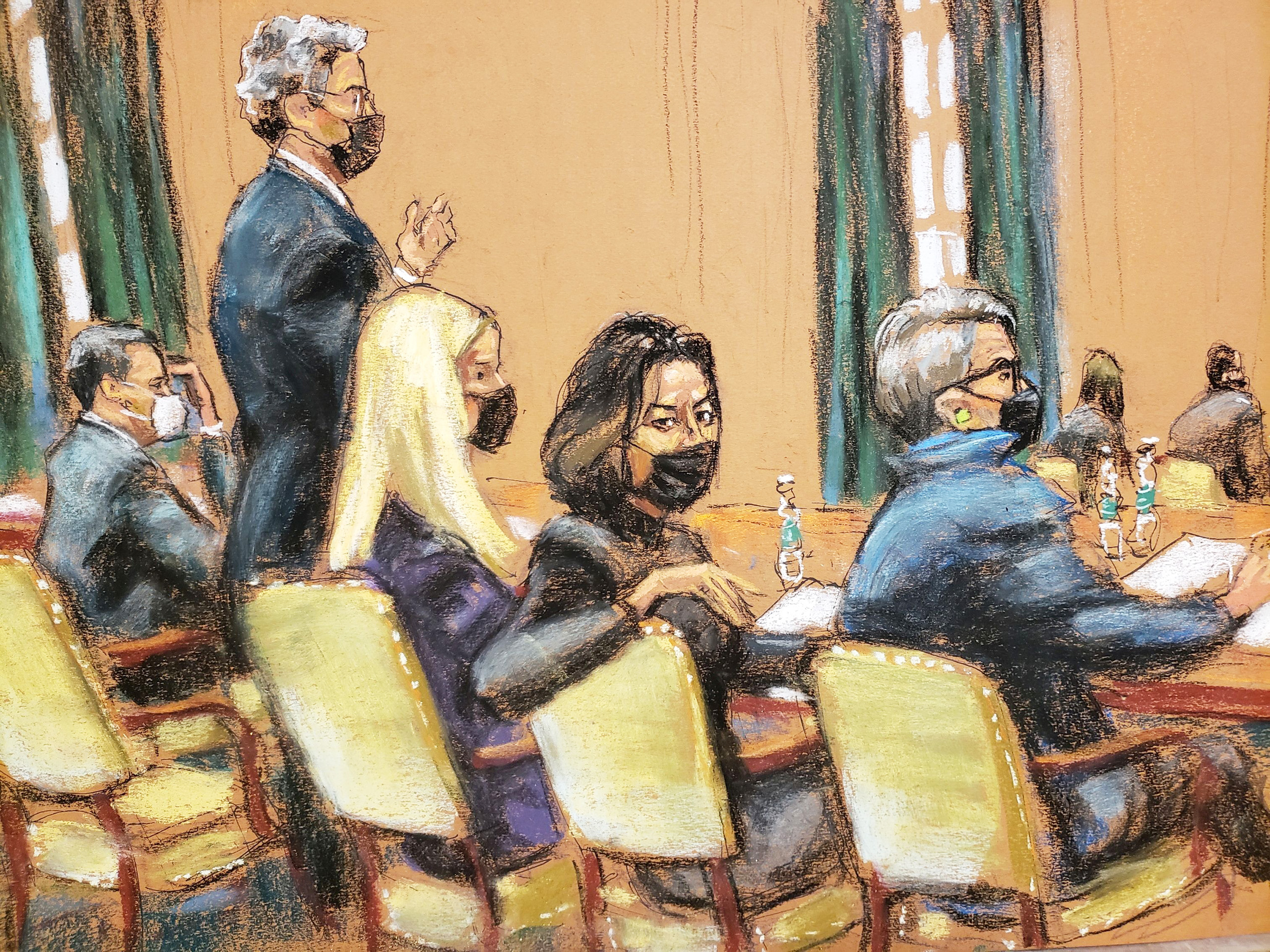

Yet, as the titles of those books suggest, it’s the perpetrators rather than the victims who have stolen the limelight. Australian writer Lucia Osborne-Crowley’s brave and immensely readable book, The Lasting Harm, does the opposite, focusing instead on the life stories of four survivors who testified at Ghislaine Maxwell’s trial in 2021. As a survivor of sexual assault, an award-winning writer on trauma and one of the few reporters who sat in the courtroom every day of trial, Osbourne-Crowley is uniquely poised to write a book that is at once an enthralling courtroom drama, a meditation on suffering, a biography of survivors and an urgent call for law reform.

In case you’ve forgotten, Ghislaine Maxwell was a British socialite with a toothsome smile and expensive cropped black hair who was convicted in 2021 of five counts of sex trafficking. She was found to have procured girls as young as fourteen for her billionaire friend Jeffrey Epstein, and sometimes to have participated in assaulting them. The Lasting Harm shuttles between the Maxwell trial, the stories of the victims, the evidence of how grooming works and analysis of sexual trauma’s impact on memory, bodies and psyches. Yes, it’s gruelling reading — though the author does an excellent job of packaging the story in chatty prose, a pacey narrative and vivid courtroom scenes.

Osbourne-Crowley divides her narrative into five sections, moving from the trial to the verdict, via the stories of women not permitted to testify, to the sentencing and its aftermath. Running through each section are the conjoined themes of trauma and grooming, linked because Maxwell could best inculcate trust and normalise abuse for women who were already vulnerable or suffering, “facing a chasm of unmet needs.”

We meet Carolyn, who came from extreme poverty and was sexually abused as a child; Jane, whose father had died suddenly and whose impoverished mother was diagnosed with bipolar disorder; Annie, whose single mother was struggling to raise two children; and Kate, whose single-parent family was also financially hard-up. Each of these women was defined by their dreams as much as their disadvantages, which Maxwell and Epstein encouraged and exploited by lavishing them with gifts, scholarships and entry into exclusive schools.

As Osborne-Crawley illustrates in novelistic detail, Maxwell was the one who would first meet the young women, sometimes by strategically walking her dog to spark a conversation. She would invite them back to meet Epstein, charm them with her erudite conversation, and eventually ask them to perform massages on her friend to normalise physical intimacy before the rapes, trafficking and violence.

Where narratives of trials usually start with the crime that compelled each person into court and end with the verdict, Osborne-Crowley searches for a longer and larger story. What made the women susceptible to such victimisation and how do the effects of that abuse go on to shape their lives and loves? As she writes of Carolyn’s story, “It laid bare in an excruciatingly honest way, just how severe the life-long effects of trauma really are… how trauma in childhood completely alters the course of our lives; the way it leaves us vulnerable to addiction, self-loathing and more trauma; the way it traps us in a cycle of violence and shame; the way it refuses to let us go.” Osborne-Crowley knows this because she herself was groomed by her gymnastics coach at a very young age and then raped at knife point as a teenager.

In court, victim-survivors find that their symptoms — which Osborne Crowley identifies as drug-addiction, self-harm or a susceptibility to abusive relationships, among other things — are a prompt for efforts to place in doubt their credibility, morality and memory. In the media, survivors who write about sexual abuse are accused of bias or a lack of objectivity. The same can be said of jurors, as happened in the Maxwell trial when a retrial was demanded after one of the jurors eventually confessed to being a survivor of abuse.

Osborne-Crowley attacks these arguments head on. Yes, she says, she is biased. We all are, particularly those jurors, judges or journalists who subscribe to rape myths — who ask what a woman is wearing when raped or wonder why a victim may continue to contact their abuser. But the problem goes deeper than this. To suggest that a juror should be excluded because they have been a victim of abuse and are therefore incapable of adjudicatory reasoning is absurd, she argues. It suggests that “they are fundamentally damaged in some way, that victims of other crimes are not, and that they should be excluded from participating in certain aspects of societal life as a result.” As for the experience of victims giving testimony, the “presence of these symptoms is not proof that the trauma they are describing didn’t happen. It’s more likely proof that it did.”

This is all excellent analysis, but Osborne-Crowley could also have asked why we think these things and how they came to be enshrined in law. Having an idea of why these ideas emerged will surely help to dismantle them.

I would have liked her to go to the library and read some books rather than phoning psychologists or experiencing minor epiphanies about epistemic injustice in court. An abundance of feminist literature analyses the Judeo-Christian origins of rape law: how, unlike other offences, rape was a “moral” crime in which the taint of the offence passed from perpetrator to victim. Unlike other victims, whose credibility was enhanced by their closeness to the offence, a rape victim’s authority was lessened.

Osborne-Crowley draws on the growing body of work on defendants who are victims of crime when she explores how many of the women who testified had prior convictions. But she doesn’t extend the analysis to Maxwell herself. To my mind, there is a gaping Maxwell-sized hole in this book, and this is a shame because we lack critical analyses of women who perpetrate sexual assault.

We tend to assume that women who commit serious crimes are either monstrous or mad — just look at all the spiders, monsters and animals infesting the titles of the books on Maxwell and Epstein. Women are measured against the model of passive femininity and any deviation judged to be abnormal. We’re told by the prosecution, with whom the author agrees, that Maxwell was a “dangerous” and “sophisticated predator who knew exactly what she was doing.” Another victim impact statement says that “Maxwell is today the same woman I met almost twenty years ago — incapable of compassion or common human decency. Because of her wealth, social status and connections, she believes herself beyond reproach and above the law.”

But what if Maxwell was in fact very human; what if we acknowledged that humans have quite a long history of inflicting pain and violence on each other? What if we interrogated how someone like Ghislaine Maxwell came to exist at all?

Osborne-Crowley clearly considered that enough has been written about Maxwell, but I’d argue that what exists is patently simplistic — she’s either an ogre or a victim of Epstein. Osborne-Crowley could have used her talents to give us a more complex picture.

When the sentencing hearing began, the defence told the story of Ghislaine’s abuse at the hands of media tycoon Robert Maxwell, her “narcissistic, brutish and punitive father who overwhelmed her adolescence.” But Osborne-Crowley only affords this a few paragraphs. She assumes that the argument is cynical and so omits much of the supporting testimony, including that of Maxwell’s psychologist sister, who described how Maxwell smashed young Ghislaine’s hand with a hammer for misbehaving, how she had to perform on cue for guests and how she entered a relationship with Epstein as soon as her father died.

None of this makes Maxwell any less abusive. But it’s possible to be both a victim and a perpetrator; Ghislaine supplicated to powerful men because this is what she learned from a young age, but she also wilfully engaged in sexual abuse. To my mind, it would do more justice to the victims if we acknowledged the complexity of the situation rather than subscribing to a simple binary of victim and aggressor. This may mean analysing Ghislaine’s family relationships but it also means examining contemporary social factors that teach women to base their sense of self on male approval or breed a culture of entitlement among the wealthy.

In many ways, the kind of analysis I’m advocating doesn’t fit with the genre of trauma literature, to which The Lasting Harm is indebted. Books in this field bear the imprint of pop-psychology: humanity is reduced to symptomology; psychological studies are elevated to a science and psychologists are crowned our new high-priests. Osborne-Crowley, for instance, implores courts to consult “an unbiased, qualified expert witness” on the effects of trauma on memory “in every trial,” although she disagrees with the psychological evidence adduced by the defence, which might have suggested to her that this “science” is somewhat imprecise, provisional and subjective.

Then again, the other hallmark of trauma literature is the empirically dubious assertion that telling stories about trauma will cure suffering, which of course makes heroes out of journalists. As I read the book, I found myself musing on the mutually reinforcing yet analytically circuitous relationship the two professions, journalism and psychology, seem to have developed.

My concern is not just with the simplistic or vague nature of psychological studies. It is also that Osborne-Crowley’s proposal could be disastrous for survivors forced to fit their stories into static and universalising therapeutic models. Women who kill their abusive husbands out of self-defence, for instance, have found their legal success to be dependent on their exhibiting the symptoms of “battered woman syndrome.” Victims of sexual abuse could meet a similar fate. I have no doubt that in many instances trauma results in “substance addiction… eating disorders; addiction to abusive relationships and chronic self-harm,” as Crowley tells us. Or that it freezes memory. But this doesn’t always happen to every person.

In fact, in some instances symptoms might include studying very hard because the victim feels they need to succeed at school, or settling down, marrying and having children because they want security. Symptoms like these would not be legible in court. Calcifying a narrow range of negative traits into diagnostic symptoms and legal criteria is overly prescriptive and would create yet another way for victims to fail.

One of The Lasting Harm’s many virtues lies in the fact that Osborne-Crowley is legally trained, which makes her an excellent companion during the trial, carefully explaining how the “facts” are severely constrained by the rules of evidence and offering some sage suggestions for how the law could be reformed. Removing the statute of limitations for child sexual assault in Britain would be a welcome move, as would reform of Australian defamation law where it has been shown to silence victims and protect abusers.

I am less convinced by her suggestions that expert psychologists should be incorporated into jury directions and the defence prevented from questioning litigants about inconsistent memories. This latter argument would severely erode the rights of the defendant in a context where a guilty verdict means prison.

I also found it odd, in light of critiques of prison offered by decades of feminist activism and more recently the Black Lives Matter movement, that Osborne-Crowley didn’t examine alternatives to criminal law. Of course, this is a very complicated area, and we couldn’t expect the author to devise concrete solutions, but some discussion of the debate would have been useful lest carceral feminism be inserted by stealth into proposals for law reform.

Osborne-Crowley’s impressive narrative skills, and her empathy, legal analysis and feminist argument, make The Lasting Harm an excellent piece of long-form journalism deserving of the widest audience. With deeper thinking and more time spent researching, reading and writing, it could also have been a brilliant book. •

The Lasting Harm: Witnessing the Trial of Ghislaine Maxwell

By Lucia Osborne-Crowley | Allen & Unwin | $34.99 | 336 pages