GEORGE ORWELL once called Britain “the most class-ridden country under the sun.” But as the historian David Cannadine has pointed out, Orwell cannot (or at least should not) have been arguing that Britain was more unequal than any other country. After all, it isn’t. But Britain is decidedly “class-ridden” in the sense that it remains obsessed with class.

The recent royal nuptials might have been a PR boon for the monarchy, but they also provided a predictably apposite occasion for this obsession to find suitably rich expression. The monarchy is admittedly rather more popular these days than during the unpleasantness of the 1990s, and one sign of its renewed vigour is that “The Firm” felt confident enough to deliver a very flamboyant humiliation to Tony Blair and Gordon Brown by neglecting to invite these two former Labour prime ministers along to the wedding. Kathy Lette scored an invitation, as did the Beckhams and Elton John. But apparently even a decade as prime minister and the reputation of having saved the monarchy from itself are not enough these days to get you a ticket into Westminster Abbey during periods of peak demand.

That the monarchy remains a pillar of this hierarchical society is no less evident. If there is one thing that everyone in the country now knows about the Middletons, it’s that they run a party goods firm. They might be very rich, and Kate – or Catherine as she’s now called – might look like a princess. She might even have attended “£23,000 a year Marlborough College,” as it’s invariably described – and once you know the annual fees, you also know what you’re dealing with. But when the relationship between Kate and Will was called off for a while a few years back, the story did the rounds that Prince William’s posh friends call Kate’s mum Carole “Doors to Manual” because she was once an air hostess. And there was recent press coverage that made it clear that Will’s grandparents had been remarkably dilatory in making the acquaintance of the Middletons; they supposedly slipped in an invitation to the palace shortly before the wedding. Whether any of this is actually true is rather beside the point. That someone might have even represented it as true speaks eloquently for the ways in which class still matters in Britain.

That Kate was jolly lucky to have won her prince was an undercurrent of much of the media’s class obsession – without anyone putting it so impolitely. A historian in her late twenties somewhat sheepishly admitted to me just before the big day that the wedding was a matter of great interest among her friends of a similar age, young women who had spent their teenage years fantasising about catching the prince and who, even now, hadn’t quite given up hope that he might yet see the error of his ways. By contrast, one always sensed that quite a lot of people felt Charles had been rather lucky to catch Diana who, after all, was at least an aristocrat. She and the Spencers had a place in the pecking order in a way that Kate and the Middletons do not.

In recent weeks, public angst about class has turned to the “chav,” who is something like a “bogan” or “westie” in Australia. You would imagine that the sheer number of scandals that have arisen from careless tweeting would by now have prompted a little more circumspection, but not on the part of a certain Lib Dem peer: “Help. Trapped in a queue in chav land. Woman behind me explaining latest EastEnders plot to mate while eating largest bun I’ve ever seen.” The baroness later explained that she hadn’t meant any offence. But as the Guardian’s Polly Toynbee has commented, replace “chav” with “nigger” or “Paki” and you see the extent to which contempt for the working class is no less acceptable among some of Britain’s educated elites than disdain for Islam.

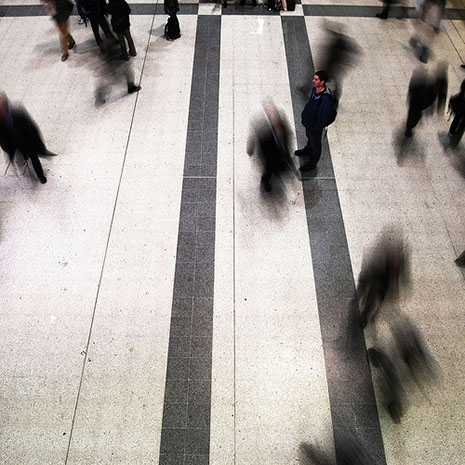

This is hardly surprising, because there’s very little common ground on which Britons of different classes now meet. They live in different suburbs, send their children to different schools, pursue different leisure activities and consume different media. They continue to speak in different accents. The royal wedding was supposed to be an occasion on which all classes joined hands in a national celebration. Perhaps it was; but for many, it was simply a welcome day off and a grand excuse to head for the pub. A list of royal street parties planned for London made it plain that you were much more likely to find one in bountiful Bromley than battling Barking.

As for much of the last century, education remains the main site onto which British people project their anxieties and fantasies about class. Schools and universities, of course, have long been treated as essential instruments in effecting social mobility. “Equality of opportunity” and “meritocracy” are now such warm and fuzzy goals for the political class, whatever their political stripe, that it’s easy to forget that the sociologist who coined the latter term, Michael Young, also the founder of the Open University, did so with a more or less pejorative purpose.

YOUNG’s brilliant 1958 satire The Rise of the Meritocracy was in essence a warning about the dangers of a world in which the successful were enjoined to believe that they enjoyed their success as the direct consequence of their own merit. Supposedly written as a doctoral thesis in AD 2034, in Young’s meritocracy “the eminent know that success is just reward for their own capacity” while “the inferior man has no ready buttress for his self-regard.” Those who achieved a lowly station in life had nothing to blame but their own lack of merit. This was a transparently fair society in which “as a matter of quite elementary justice, neither man nor child should be judged stupid until he was proved to be.” (The creepy, incessant monitoring of personal intelligence in Young’s dystopia may well have been the model for reform of the education system under New Labour, with its endless tests and examinations. It certainly resembles it.)

Yet the idea of meritocracy retains a powerful allure. In the guise of the future author, Young remarks that “intelligent people tend, on the whole, to have less intelligent children than themselves; the tendency is for there to be continuous regression towards the mean – stupid people bearing slightly more clever children as surely as clever people have slightly less.” Although it’s not yet 2034, it’s possible to test this theory by reference to the Young family at least, since Michael’s son Toby, a journalist and broadcaster, is one of the principal spokesmen for Britain’s “free school” movement.

Over the last year the Conservative–Liberal Democrat government has extended the Labour government’s policy of allowing certain government schools to be run independently of local authorities. Where Labour encouraged privately sponsored academy schools to take over from “failed” comprehensives, the Tories have permitted schools ranked “outstanding” to transform themselves into academies and escape the supposedly dead hand of bureaucracy. But the coalition government has also given its support to the establishment of free schools. Here, apparently, is David Cameron’s “big society” in action: local people banding together in voluntary endeavour to achieve a common goal.

The first free school to gain government approval was the West London Free School planned by Toby Young. It will provide “a classical liberal education that’s every bit as good as that provided by Britain’s best independent schools but which is accessible to all, regardless of income, ability or faith.” Parents who want the best education for their children will no longer have to pay high fees to send them to an independent school, or move to an area – invariably middle-class – where the local comprehensive is acceptable to them.

Toby Young makes the fair point that because of this tendency for the quality of a local school to depend so heavily on the socioeconomic status of the area in which it is located, parental income plays a critical role in determining the quality of the education a child receives. Under his proposal for a free school, run by parents and teachers rather than local authorities yet still governed by state admission rules, an excellent education is accessible to all. As Young puts it, he hopes his plan for “comprehensive grammars” would honour his “father’s inclusive philosophy, but without the unhelpful egalitarian baggage.”

Needless to say, the free schools have their critics. They point out that at a time when other schools face government cuts, money is being invested in these new facilities. It is said that they will create a more seriously divided state school system and weaken existing schools by diverting both scarce resources and middle-class children from existing comprehensives.

In some ways, however, the most serious objection to the free schools – and, indeed, to much of the present government’s “big society” baggage – is given away in a throwaway comment by Young himself. He estimates that as the leader of the project he’s “devoted between forty and sixty hours a week to it for the last eighteen months.” His wife jokes that if he had been equally assiduous in pursuing his career, he could send his kids to Eton.

Yet who but a member of the British elite would be able to plough up to sixty hours a week of voluntary time into a project of this kind? Only the very highly motivated and well-off are likely to be able to muster the time and resources necessary to set up and then maintain such an institution. And the very same cohort is likely to dominate the strategic direction of such schools once they open, thereby making a mockery of the vision of dispersal of power that underpins the whole big society enterprise.

Whereas, if they wished to do so, parents have had to rely on their own resources to create a private school, the Tories and their Lib Dem friends ensure they can now pursue their ambitions compliments of the British taxpayer. This is admittedly not so very different from the case with private schools in Australia, which even when they have more money than they know what to do with, still draw substantially on the public purse. But we have become so relaxed and comfortable about this that we fail to see how peculiar paying vast sums to already rich schools must look to others – especially to others such as the British with their class angst.

A similar pattern is suggested in the even more recent proposal for a New College of the Humanities in London, a brainchild of the philosopher A.C. Grayling. It will assemble a team of celebrity academics including Richard Dawkins, Niall Ferguson, Linda Colley and David Cannadine and charge its pupils £18,000 a year for the privilege of attending their lectures – approximately double the already hefty fees most students face under the recent increases.

Unsurprisingly, the proposal is controversial at a time when government cuts are forcing some very tough decisions within universities about what they can offer prospective students. Terry Eagleton called it “odious.” Where some British left-wing moderates such as Anthony Crosland had once viewed the United States as a model of classlessness that Britain should emulate, Grayling’s college represents for its critics the nightmare of an elitist American private university system about to run riot in Britain. But unlike the famous US institutions it is supposedly seeking to emulate, this “private” college – if it does get off the ground – will depend substantially on public resources. It will need to enter into an agreement with an existing college for library resources, and it proposes teaching parts of the University of London curriculum. It also seems that its celebrity lecturers will not, in most cases, be resigning their present posts, which is certainly a good way of saving on salary bills.

All of this is a far cry from Michael Young’s Open University but not so very far from his meritocracy. Young’s satire made it clear that most members of the meritocracy would be the offspring of other meritocrats. In modern Britain, meanwhile, the rich and successful know that, like the “chavs” they despise, they are only getting their just deserts. •