In late 2022 the director of the Adelaide Festival Louise Adler made an unexpected suggestion. She recalled my writing about politics in the plays of Tom Stoppard — why not interview him? After all, Hermione Lee had recently published her definitive Tom Stoppard: A Life. Perhaps we could get the two together, and film the conversation to open that year’s festival?

This seemed an unlikely proposition. Sir Tom, then in his middle eighties, was unlikely to travel. And Dame Hermione was much in demand. Her Stoppard biography marked a change in direction for a scholar whose reputation rested on biographies of great women writers including Elizabeth Bowen, Virginia Woolf, Edith Wharton and Penelope Fitzgerald. As she noted, such subjects were “safely dead” and couldn’t answer back. But Stoppard was then Britain’s most acclaimed living playwright. Would Dame Hermione agree to discuss her latest book with its subject?

Louise is never daunted. If I could use Oxford contacts to reach Dame Hermione, said Louise, she and the festival would approach Stoppard’s agent. It was a good call. Dame Hermione proved delightful and generous at every point, Sir Tom was happy to meet, and arrangements fell into place. A film crew was arranged, leave taken, flights booked.

By this stage Stoppard had been a significant figure on the theatre stage for half a century, since Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead dazzled the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 1966. His most recent work, Leopoldstadt, was on stage in New York, filling the theatre every night with an exploration of a Viennese family devastated by the Nazis.

The echoes with Stoppard’s own life — born in 1937 to a Jewish family, sent for protection from Czechoslovakia to Singapore only to be caught up in the Pacific War — were clear. Stoppard, his mother and elder brother, left on one of the last ships before the Japanese arrived. They understood they were being evacuated to Australia but landed instead in colonial India. Stoppard’s father, a doctor scheduled on a later boat, didn’t survive. Eventually a new life in Britain provided safety, a Czech accent overlaid by English boarding school.

What followed was an extraordinary career in theatre and film, along with a novel, a knighthood and fame. Such success often attracts wry comment, if not worse. But as fellow playwright Simon Gray once said, “It is actually one of Tom’s achievements that one envies him nothing, except perhaps his looks, his talents, his money and his luck.”

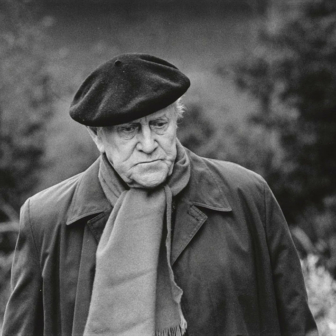

In early January 2023, my partner Margaret and I arrived at the assigned address, a rambling Notting Hill apartment owned by Stoppard’s wife, Sabrina Guinness. This artistic space, with a personally signed Andy Warhol in the hall, was their bolt-hole, Guinness told us: the couple spend most of their time in Dorset. Dame Hermione and Sir Tom were waiting. Sabrina made soup in the kitchen while the film crew set up lights and cameras. Sir Tom, shy even in this private setting, smoked continuously and shuffled nervously in and out, checking arrangements.

Finally the biographer and her subject sat side by side, the cameras rolled, and we opened with why they agreed to cooperate on an authorised life.

“Well, I was a very guarded person — and still am,” said Sir Tom, “and was quite guarded about having a biographer. But one or two biographers had, as it were, threatened and I knew Hermione… I thought, well, I’m going to have my life written. I’d much rather it were written by her.”

And so into the life, in part captured in the many letters Sir Tom wrote to Marta Becková, his mother.

“My mother had kept a lot of letters from me,” he recalled. “I was a dutiful letter writing son from boarding school onwards. First of all, I just thought my reputation would never survive my schoolchild letters. But finally I just stopped caring and I asked my secretary… to read them and say, is there anything in here that matters? And she got part of the way in before I decided, to hell with it.”

Dame Hermione smiled. “For a biographer to have this kind of look at this kind of access is quite extraordinary.” Sir Tom started writing weekly to his mother from 1948 and finished in 1996, the year Marta died. “Of course, you’re not telling her everything because she’s your mother,” Stoppard noted. “But you clearly wanted her to feel she knew what you do.”

The plays followed, from early comedies such as Jumpers, reflections on the media in Night and Day, colonialism in Indian Ink, the fate of Eastern European dissidents in Rock ’n’ Roll, infidelity among theatricals in The Real Thing. Plays of ideas followed, including Arcadia about chaos theory, Hapgood on physics and spies, and the challenge of consciousness in The Hard Problem. Along the way a novel, translations and much work on film scripts, with an Academy Award for co-writing Shakespeare in Love.

Late in the career came several ambitious works: The Invention of Love in 1997 about the classicist and poet A.E. Housman, revived this year in London with Simon Russell Beale in the lead role; a 2002 trilogy, The Coast of Utopia, about Russian revolutionaries in the 19th century; an ambitious adaptation for television of Parade’s End by Ford Madox Ford; and, finally in 2020, Leopoldstadt.

Sadly, none of these later works have made it to the stage in Australia. The Invention of Love is long and scholarly, a brilliant study of a lonely academic life. Leopoldstadt imposes huge demands as forty-one actors portray overlapping generations over nearly seventy years.

In the closing moments of that play a young boy appears on stage. He was taken to Britain just before the Nazis seized Austria, and returns as a smug English patriot, seemly oblivious to the loss of his wider family. Amid the wreckage of the Holocaust, he is told that remembering matters — if you live without history, you throw no shadow.

Was Sir Tom writing about himself, a man who only learned later in life the full fate of his extended family? Dame Hermione had sat in on preparations for Leopoldstadt and sensed a profoundly autobiographical moment, but Sir Tom denied it when she asked.

“No, it’s about a Viennese mathematician, for God’s sake,” he told her.

Dame Hermione wasn’t fooled. When the cast reached the end of the first full run-through “there was not a dry eye in the rehearsal room” she recalls. Sir Tom asked the cast “is it all right for me to cry at my own play?”

Our discussion closed with a quote from the legendary producer — and Sir Tom’s close friend — Mike Nicols, who describes Stoppard as that most rare creature: a writer who is happy.

Sir Tom smiled at the memory. “It’s a nice thing to have said about one. But I honestly think I’ve had my fair or unfair share of miserable times and anxieties.” He suggests that everyone is a combination of “a very happy person and a very anxious person. We are all a bit of both.”

The interview complete, after thanks and cups of tea, we departed with the film crew. The footage would be edited in the weeks ahead, then played to a full house at the Adelaide Town Hall, introduced by premier Peter Malinauskas as the first event of the 2023 festival.

After the screening Sir Tom joined us by video, speaking with a panel which included the remarkable Australian playwright Suzie Miller and legendary theatrical director Simon Phillips, who recalled rehearsals with Sir Tom. A local reviewer described the conversation as “engaging, witty and thought-provoking as one of Stoppard’s plays.” (For some years the interview was available on ABC iView.)

The Tom Stoppard I encountered was reflective, tough-minded, clear about what he believed and why. There was spark in exchanges with Dame Hermione but melancholy too, a man looking back over a life, pondering still the luck which broke his way so young. Sir Tom understood that art finds its sources in unexpected places.

“All my life,” he said, “I have depended on the kindness of the subconscious.”

Yet the commitment to craft was impossible to miss. “It is a wonderful thing to be a writer because there is just you and it,” he said. “It is not dependent on anybody else. I am not the kind of person who shows work in progress, reads it to my wife over breakfast, nothing like that. I just wait until it is done and then send it to somebody.”

This Tuesday night theatre lights in the West End will dim in memory. Vale. •