The East Kimberley, one of Australia’s harshest and most visually stunning landscapes, has a population of roughly 11,000 people, of whom around 4700 identify as Indigenous. The region’s main language groups traditionally included Miriwoong and Gajirrabeng around Kununurra in the north, Malngin over the Territory border to the east of Purnululu National Park, Jaru in the south between Halls Creek and Balgo, and Gija to the north and southwest of Warmun (formerly Turkey Creek), midway between Kununurra and Halls Creek.

The number of active and fluent speakers of these languages is low and declining. Among the Indigenous population aged under twenty-five — half the region’s Indigenous population — the lingua franca is primarily English and Kimberley Kriol, a relatively recent hybrid. The 2016 census listed 2315 Kriol speakers and just 158 Gija speakers.

Colonisation came late to the East Kimberley. The four decades of frontier violence after the pastoral invasion in the early 1880s caused untold — and largely unrecorded — loss of life as a result of disease, economic and social disruption, and overt violence. Today’s Aboriginal population of the East Kimberley are the descendants of the survivors of that forty-year war — survivors who made an accommodation with the owners of the cattle that had disrupted their waterholes and destroyed the basis of their subsistence livelihood.

The incentive for Aboriginal people to detach themselves from their subsistence lifestyle, attach themselves to missions and work on pastoral stations was reinforced by the imperative to avoid the pervasive violence of pastoralists and police, and possible exile to Rottnest Island and other prisons. Working for pastoralists at least gave traditional owners continued access to their Country, and time off for ceremonies during the wet season, and removed the risks of relying completely on subsistence.

Despite their concessions, Kimberley people have strenuously sought to maintain their cultures and languages. They have established cultural and language resource centres across the region, and many of the region’s schools support language maintenance. The Ngalangangpum School at the Warmun community and the Purnululu Community School at Frog Hollow, or Woorreralbam, both in the heart of Gija Country, offer instruction in English and Gija. But these cultural maintenance projects increasingly compete against the pressures of modernity and commercialism.

This is the context for Aboriginal Studies Press’s recent publication of Gija Dictionary. Its authors, Frances Kofod, Eileen Bray, Rusty Peters, Joe Blythe and Anna Crane, have produced an extraordinary linguistic resource for Gija people, derived from thirty-plus years of linguistic research, especially by Kofod, and the expert language skills of Gija co-authors Bray and Peters and the linguistic contributions of around sixty other Gija collaborators.

This is not simply an etymological project, translating vocabulary and explaining meaning; in many respects, it allows Gija speakers — and learners — to see themselves and their culture in a linguistic mirror. It reflects and documents the sophisticated worldview, developed over eons, that enabled Gija society to thrive in one of the most severe environments in Australia.

Gija Dictionary opens by introducing Gija language and Country, with an excellent map illustrating the extent of Gija Country’s approximately 30,000 square kilometres. Individual chapters deal with spelling and pronunciation, word classes, grammar and, importantly, Gija relationships. The core of the book, the Gija-to-English dictionary, defines in excess of 5000 words and phrases, and a separate and more succinct English-to-Gija word-finder identifies the Gija terms for more than 3500 English words.

But merely listing the contents doesn’t do justice to the effort and innovative thinking that have gone into producing a dictionary useful to Gija speakers, to future Gija learners, and to teachers, health workers and others interested in learning Gija.

Importantly, the introductory chapters explain the conceptual underpinnings of the Gija language: the fact, for example, that topographical directions (upstream/downstream; uphill/downhill) are just as important as cardinal directions. Interspersed through the text are more than ninety photos of current and past community members, local wildlife and significant locations, each labelled with a phrase in Gija, thus encouraging readers to look up the words to interpret the photo.

Not surprisingly, the dictionary is replete with vocabulary that reflects the social and cultural concerns of traditional Gija speakers, including their outdoor lives and focus on being on Country. Often, Gija terms have no equivalent word in English: for example, the English-to-Gija word-finder lists around twenty terms for different actions associated with the concept “walk.” Or, to pick terms almost at random, galayi means to shade your eyes with a hand while looking at something; galayyimarran refers to being in the brightness at sunrise or sunset; dooloo means to make smoke as a signal or as part of a smoking ceremony.

The word-finder also demonstrates the centrality of spears to traditional Gija life. It lists five different types of spear and six different types of spearhead, along with terms for using spears, such as hooking onto a woomera, straightening a spear, and throwing a spear at someone. My favourite is the word bililib: to drag a spear surreptitiously with your toes.

In Gija culture, the relationship between speakers is always significant. The Gija Dictionary’s definition of garij, calling someone’s name aloud, notes that this is considered an action with serious consequences depending on your relationship with the person named. It also includes a short explanation of the terms used in joking relationships between individuals denoted as ganggayi.

Were I to use any of the swear words listed, Gija speakers would respond with an interjection warri-warri if I was swearing at my parent or uncle or aunt, or yigelany if I was swearing at my brother or sister. If I swore at my brother- or sister-in-law, they would make a kissing noise and two tsk tsk clicks. They would then look away, use their hand to signal me to stop swearing, and then move their hands to block their ears.

Just as the dictionary reflects Gija culture for Gija speakers and learners, it provides a window that allows non-Indigenous readers to glimpse the Gija way of experiencing the world. Gija speakers’ grafting of new meanings onto old terms to incorporate non-Indigenous categories and technologies demonstrates their culture’s inherent dynamism.

Examples of Gija linguistic repurposing abound in the dictionary. For example, it identifies two words for police officer: mernmerdgaleny (literally, one who is good at tying up) and ngerlabany (having string or rope). In a similar vein, the word dimal, for boat, appears to be an appropriation of the English word “steamer.” A note explains that this is an old word used by Gija people, derived from the Aboriginal pronunciation of steamer and referring to the steam ships that transported Aboriginal prisoners to Rottnest Island.

Or take the word lendij, which means either to write or to read, but also to pressure flake a stone. The word came to mean writing because the old people saw it as a similar action to pressure flaking stone spearheads with a small hard stick called a mangadany. The transition from writing to reading followed naturally.

Other words have similarly been adapted. Ngoorr-ngoorrgalill means car (good at growling), with similar variants for car key and car engine. Wingini, which originally meant to spin around and around on the spot, now refers to being drunk. With a gender change, the term for wedge-tailed eagle (wirli-wirlingarnany) refers to an aeroplane (wirli-wirlingarnal). The word for photograph, ngaaloom, is repurposed from the word for shade and shadow.

What these words show is that Gija speakers, while anxious to maintain their language, have been prepared to incorporate non-Indigenous technological, cultural and institutional concepts within the Gija language. This engagement and accommodation has always been strategic, aimed at conceding what can’t successfully be defended, but also reflects a determination to find ways to protect what is important to Gija culture. The dictionary’s presentation of a unique Gija language, culture and worldview provides tangible proof that Australians inhabit a multiverse rather than a narrow social, economic and cultural universe.

While Australian English has similarly incorporated Indigenous vocabulary (boomerang, kangaroo), it is not obvious, at least to me, that this extends to the widespread adoption of such fundamental Indigenous notions as deep respect for Country and the power of reciprocity in cementing ongoing relationships. For all the talk of pursuing social justice and reconciliation with First Nations, mainstream Australia appears unable to acknowledge the extent of the loss suffered by Aboriginal people as a result of colonisation.

Most importantly, the nation appears unable to see — really see — that Indigenous people like the Gija have been prepared to make extraordinary compromises in order to bring the endemic violence of the frontier wars to an end and, later, to survive the upheaval of the equal-wages decision in the 1960s, which led to mass dismissals of Aboriginal pastoral workers and the forced removal of their families from stations.

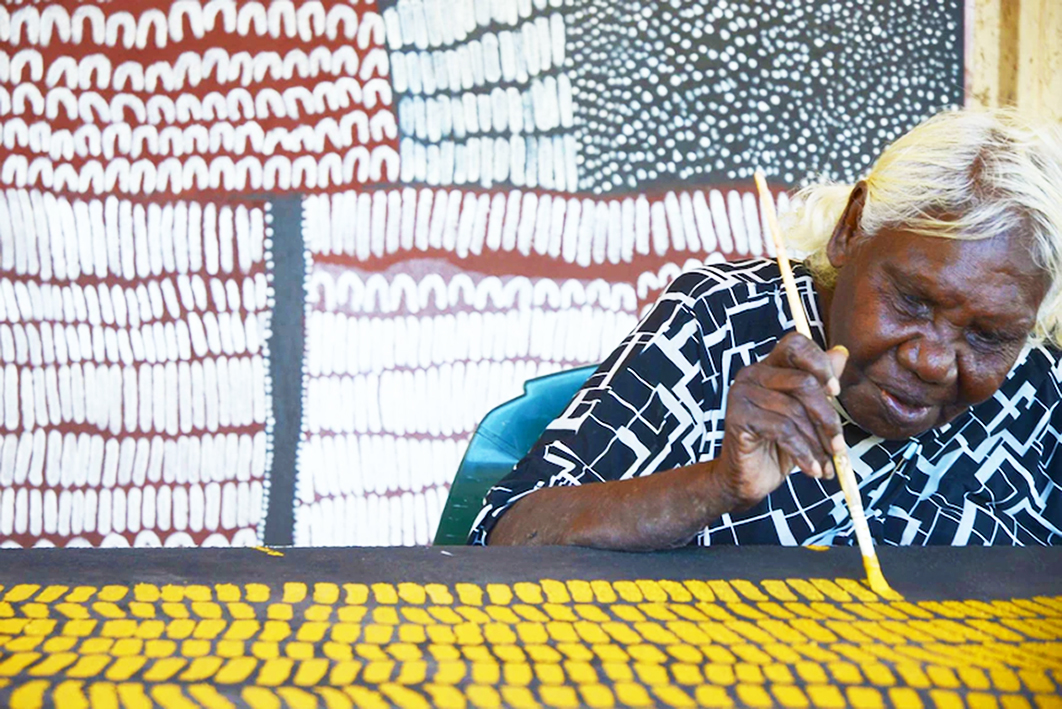

It is an extraordinary paradox that while the few hundred Gija speakers are among the poorest and most disadvantaged Australians, at least a dozen Gija speakers are represented in international art galleries from Paris to New York, and in every capital city in Australia.

While other schools of Indigenous art have equivalent international reputations, Gija artists certainly hold their own. A reproduction of a work by Gija artist Lena Nyadbi is etched on the roof of the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris and can be seen from the Eiffel Tower. Internationally known artists such as Paddy Jaminji, Queenie McKenzie, Rusty Peters, Rover Thomas and Paddy Bedford (all of whom are now deceased but contributed to and inhabit the Gija Dictionary) are the subjects of published biographies or catalogues dedicated to their art.

In putting the East Kimberley on the international art map, these artists have also put Australia on the map. The core element in their success was their knowledge of Country and the intellectual capital inherent in Gija “ways of being,” both reflected in the Gija language.

Yet the demographics of the Kimberley are changing. Modern transport, communications technology, regional economic developments, educational opportunities and even sporting opportunities have expanded the horizons of young Gija speakers. The future of Kimberley languages is no longer guaranteed. If the Gija language does disappear, we will all lose not just a language but also an alternative worldview, a way of seeing and inhabiting the world that reflects and emerged from 60,000 years of living on this land.

At its most fundamental level, as an assertion of the legitimacy of Gija perspectives and worldview, the Gija Dictionary represents the next stage in the Gija’s 140-year quest to make their way into the future on their own terms. Its publication is an opportunity for the nation to acknowledge the inherent legitimacy of an alternative Gija worldview and to recognise the strategic compromises and accommodations imposed upon, and made by, Gija people.

Of course, the Gija are not alone in this respect. Hundreds of First Nations have experienced similar histories since 1788. Such an acknowledgement must involve — at the very least — taking effective action to repay younger First Nations generations with the skills that will assist them to continue living successfully in an increasingly multicultural Australia and world, along with substantive financial and policy commitment to language support and maintenance.

First Nations’ languages are a strategic cultural asset for the Australian nation and its people, yet they all confront existential risks. If reconciliation means anything, it means ensuring the survival of these intellectual and cultural assets. The value of the Gija Dictionary is that it is a modest but determined and tangible step in that direction.

Within two years, the nation may have a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous Voice. By 2050, will the Indigenous Voice be limited to communicating in English, or might it youwoori (speak loudly), gooyoorrgboo (speak with power to change Country), wiyawoog (speak or sing to ward off danger) or even just jarrag Gija (speak in Gija)? •

Gija Dictionary

By Frances Kofod, Eileen Bray, Rusty Peters, Joe Blythe and Anna Crane | Aboriginal Studies Press | $34.95 | 430 pages