Rebel Without a Clause: Losing the Linguistic Plot

By Sue Butler | Pan Macmillan | $24.99 | 256 pages

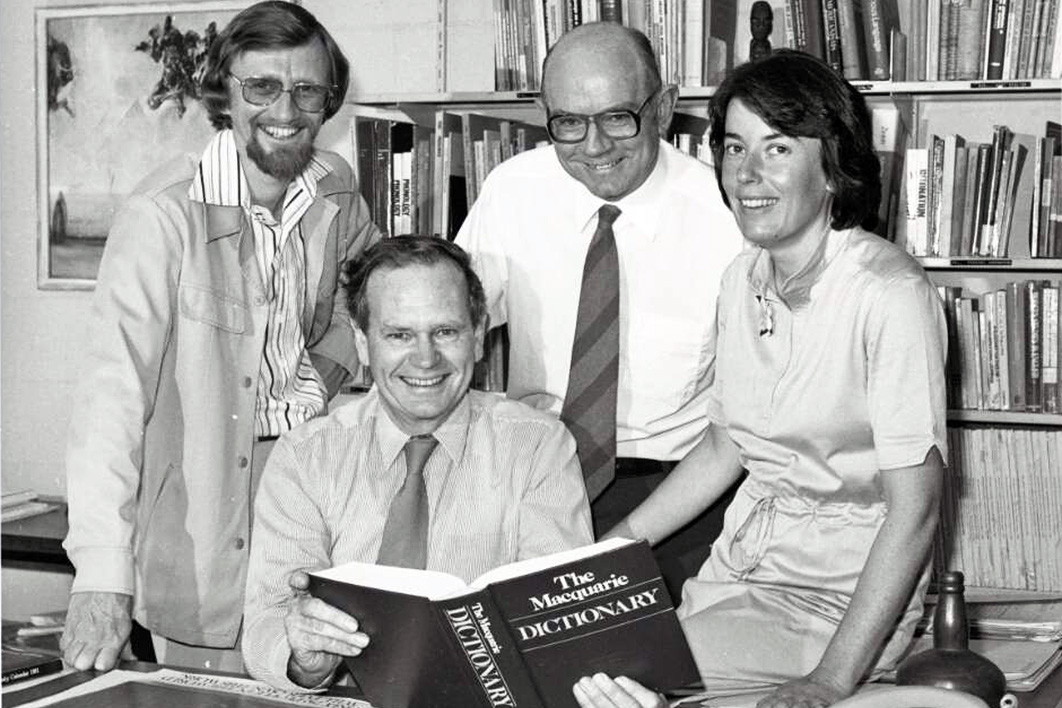

What do you do if your computer’s spellcheck fails you, or its list of definitions and synonyms doesn’t come up with the word you want? Like many Australians I turn to the Macquarie Dictionary, still mercifully available in print as well as online. Developed at Macquarie University in the 1970s and drawing on the work of key scholars in a variety of disciplines, this first full record of English usage in Australia remains one of our greatest reference works. First published in 1981, it is now in its eighth edition, with 3500 new words.

Sue Butler was there from the start, and for forty years worked on updates and revisions. Like any dictionary editor she was bombarded with suggestions for new words and a bevy of complaints about spellings and definitions. To have maintained a sense of humour while being linguistically bailed up in bars, cafes and classrooms is a rare skill.

My early enthusiasm for the Macquarie was cemented when I wanted to frame an address to the Society of Editors entitled “Rack Off Hairy Websites.” Like many people with high hopes for the web, I was already finding its multiplicity of good, bad and indifferent sites overwhelming. I was delighted to find that the Macquarie did indeed list “rack off,” with the salutation “Rack off hairy legs!” as an example.

Butler’s linguistic encounters are amusingly captured in Rebel Without a Clause. Over the years she found that she couldn’t even go to the dentist without being asked about correct pronunciation, and she reports that she still encounters teachers who persist in complaining about mis-cheev-ious children. She has long been an advocate of accepting popular usage, and is even prepared to contemplate “literally” as an emphasis marker, as in Amanda Vanstone’s declaration in 2006 that “we are literally bending over backwards.” But she still can’t come at “pro-nounci-ation,” even if it is used by one of her favourite ABC presenters. Language is always personal.

Butler spells out her governing credo thus:

Language is always changing, so it is not possible to have rigid rules. The split infinitive, for example. But it is possible to judge whether clarity has been maintained in the text or not, whether the reader or listener will sail through with perfect comprehension or struggle to keep the thread as they come up against unnecessary blockages of ambiguity or confusion.

She is pleased that Trumpisms (Microsoft spellcheck’s suggestions include an unhelpful “Truisms”) hadn’t had much impact on usage in Australia even before Trump lost. How pleasing that Clive Palmer’s imitative “Make Australia Great” got him only 18,000 votes in the recent Queensland election. (Never has so much advertising money been spent on so few votes.) Trump’s typically confident boast — “We are going to win big-league” — did get him a hell of a lot of votes, but not quite enough.

Many current expressions do upset Butler, though, and did even when, as the editor of the Macquarie, she had to take them seriously. She identifies a new cohort of phrases we could do without: “tease out,” “drill down,” “sad inditement [sic]” and “ventilating anger.” But she accepts these and others have entered the popular parlance.

She also explores the etymology of genuine Australianisms, including “grouse” and “bogan.” The latter was first used in the 1890s, when Henry Lawson encountered a hard-drinking, hard-swearing “one-eyed bogan,” though Kylie Mole took it to “the next level” (as the corporate boosters are fond of saying) in television’s The Comedy Company in the late 1980s. Butler dismisses recent suggestions that “didjeridu” might have Irish origins on the grounds that, at the point of invasion, the instrument was only to be found in remote northern Australia, far from the Irish arrivals.

When the speaker of the Victorian Legislative Assembly asked Butler whether the word “rort” could be considered “unparliamentary,” she explained that “rort” is a respelling of “wrought,” the past participle of the verb “to work.” Working the metal (as in wrought iron) was used metaphorically for working the system. Whether it’s unparliamentary is a separate question, of course, but where would parliamentary invective be today without “sports rorts,” let alone government purchases of land in western Sydney for many multiples of market value.

As you might expect for a book published in 2020, even Covid-19 gets its own chapter, so we have “self-isolated” and “social distancing,” and we all support the efforts to “flatten the curve.” Prospective migrants who want to pass the federal government’s proposed Australian English test, meanwhile, would be well advised to read Butler’s chapter on “sheilas,” and appreciate the role of those meaning-laden adjectives “bonzer,” “flash” and the less complimentary “old.” And surely we shouldn’t let anyone into Australia who doesn’t know what a “dunny” is.

As any seasoned bookseller will tell you, up to half of all Christmas book sales are for gifts. Rebel Without a Clause will appeal to lovers of language, from those of us who think people “die” rather than “pass” to those who, like Butler, are over “closure,” an invention of American psychiatry. And if you have friends or relatives whose use of language offends you — people who speak of a “fatal demise,” for instance — you can use your inscription to direct them to the appropriate chapters. •