Titanic Lives: Migrants and Millionaires, Conmen and Crew

By Richard Davenport-Hines | Harper Press | $35

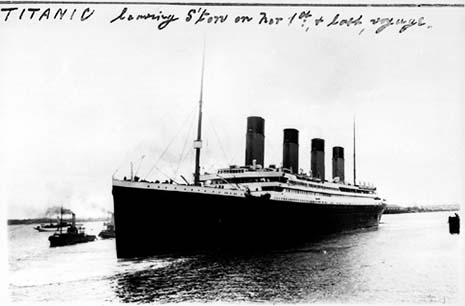

IT WAS inevitable that this centenary year would bring a fresh rush of books, articles and films purporting to offer new insights into how and why the Titanic went down after colliding with an iceberg on its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on 15 April 1912. But Titanic disaster literature is so vast and so varied that any new book has to be judged by what new light it sheds on the sinking of the ocean liner and the deaths of 1517 passengers.

Richard Davenport-Hines’s Titanic Lives does try to add something new to the familiar analysis, which links the disaster to Edwardian hubris, social and economic class distinctions and above all to maritime incompetence – notably the shortage of lifeboats, the inability of the crew to fill them, and the failure of passengers in lifeboats to aid others screaming and freezing to death in the smooth, glassy sea on a black Atlantic night.

Although he adds little to the terrible narrative of the tragedy, Davenport-Hines freshens the familiar with chapters on the lives, values, attitudes and ambitions of those involved in the tragedy – the shipowners, shipbuilders and sailors as well as the millionaires in the first-class cabins, the genteel Lyons Corner House passengers in second class, and the poor immigrant battlers in third class. While these often intensely human stories reveal the best and the worst about many leading figures in Edwardian society on both sides of the Atlantic, and about the struggles of less exalted passengers, Davenport-Hines’s best chapter remains his crisp retelling of the ship’s collision with the iceberg and the horror that followed.

It was a night of selfless courage and selfish cowardice – a night on which some married couples parted knowing they would not meet again while others faced death together stoically. It was a night when some women refused to leave the ship even as it began its plunge to the depths of the Atlantic, and of screams for help in the sea as passengers froze to death.

Davenport-Hines portrays the Titanic as a floating microcosm of Edwardian society: a mix of the self-indulgent super-rich, arrogant and condescending; the prim middle-class, proper and boring (and perhaps insecure); and the huddled masses of third-class passengers and crew members. He hints that, unlike many previous writers, he feels the wealthy have received an unfair press over the years. Unlike some, and perhaps most, previous writers, Davenport-Hines also offers a restrained judgement on the much-maligned Bruce Ismay, head of the White Star Line that ran the Titanic, who saved himself by stepping into a lifeboat as the liner was sinking. Ismay’s action, which Davenport-Hines describes as merely “impulsive” after he had helped in the loading of the lifeboats, tarnished his name for the rest of his life.

Re-examining familiar data showing that proportionally many more first-class passengers survived than second- or third- class passengers or crew members, he argues that gender was more decisive than class. Perhaps it was – but with some exceptions (an Astor and a Guggenheim died in the Titanic) the wealthy did enjoy a higher survival rate.

Moreover, although Davenport-Hines argues that the explanation for heavy losses among third-class passengers “was not malign Edwardian snobbery, but rather human failure,” he doesn’t examine whether snobbery contributed to human failure. In effect, he is challenging the thesis of James Cameron’s 1997 film, Titanic, which demonised the rich American and English passengers, as well as the Marxian analysis that has linked the disaster to class warfare.

The stratified world of the Titanic was not substantially different from wider Western society, with its obsessive pursuit of wealth and pleasure and speed, and its growing, excluded under classes. But many on the Titanic retained now-quaint notions of what it was to be “manly,” a “gentleman” and “British,” and obeyed the order, “Women and children first.” Perhaps that is why the occurrence still resonates.

Ultimately, though, the Titanic disaster is attributable to what Davenport-Hines calls “a woeful inadequacy” of lifeboats. “There had been a shambles loading them,” he writes, “and the crewmen who were put in charge of them often proved blundering or weak-nerved.” In fact, the Titanic carried twenty lifeboats of various types, and according to contemporary estimates another 500 people could have been rescued if all the boats had been filled. Instead, as Davenport-Hines notes, more than 1000 people wearing lifejackets froze to death in the water while others in nearby lifeboats failed to respond to the shrieks and cries for help that went on for an hour. The sounds haunted some survivors throughout their lives.

The loss of the Titanic was a ghastly tragedy that blighted lives in Europe and the United States for years, although ocean liners were soon compelled to carry adequate lifeboats. But apart from buffs, who really cares about the vessel in these days of super jetliners? The disaster occurred just two years before the outbreak of the first world war, which dwarfed the Titanic losses. As the twentieth century progressed, the world witnessed more wars and tragedies with previously unimaginable losses of human life. These days we may be more inured to massive death tolls and perhaps more indifferent to distant human suffering and loss. If so, that is in itself a tragedy of Titanic proportions. •