Mischka’s War: A European Odyssey of the 1940s

By Sheila Fitzpatrick | Melbourne University Press | $34.99 | 277 pages

Sheila Fitzpatrick’s remarkable new book focuses on two complex and fascinating people — one of whom was Fitzpatrick’s husband — who survived the devastating 1939–45 war and its aftermath in Latvia and Germany. She meticulously weaves a highly accessible account of the sweep of history with the lives of Mischka and Olga, the son and mother whose lives she seeks to unravel.

Two incidents that leap from the pages with shocking ferocity were both witnessed by Mischka and appear to have deeply affected him for the rest of his life. The first came on Easter Sunday 1943, when he was skiing in the Shmerl woods west of Riga and came across a series of partially covered mass graves of Jews shot by Nazis. The author records in full his chilling and unnerving description of what he saw.

The second was the bombing of Dresden, which began when Mischka was living there. Again, Fitzpatrick allows her protagonist to describe what happened. It almost defies belief that he and his girlfriend at the time survived the onslaught.

What I found surprising in both cases, however, was how Mischka documented what happened, clinically and dispassionately, as if he were a forensic scientist. But then his whole life turns out to be full of puzzles.

From childhood, he was cosseted and pampered by an overwhelming mother who was convinced he was “exceptional.” Indeed, Olga was pretty sure her son would win a Nobel Prize in his chosen field of theoretical physics. She exerted an unusually strong influence over the first thirty or more years of his life, intervening in his personal affairs as well as being his strongest advocate in his chosen career.

We know about Mischka’s life mostly from his voluminous surviving records — letters, “musings,” his mother’s letters and other documents — as well as through oral accounts from relatives and other sources. He clearly had an unshakeable belief that he was not like other men, especially in his field of physics. “I hate ordinariness and yearn for independent thinking,” he once said, yet he was never really sure whether his way of thinking about scientific problems made him inferior or superior to his peers.

“This self-doubt was simultaneously assuaged and intensified by his mother’s unwavering belief in his genius,” writes Fitzpatrick, who then quotes a letter he wrote:

First, I know — but better not admit! — that I am top. [But at the same time] I know that it is not true, that actually I am a fraud. By not admitting the first, I can keep also the second under wraps.

He was a mass of contradictions: he hated authority figures, bureaucracy and rules, yet desperately wanted to achieve good grades at university. He met the high-profile Fritz Sennheiser, professor of high-frequency physics and electro-acoustics, and founder of the Sennheiser Electronic Corporation, which would grow into one of the world’s foremost developers and producers of audio technology. Sennheiser had shown considerable interest in Mischka and offered him a job with his company, but Mischka turned it down because, he wrote, “I must not bind myself, limit my development.” Fitzpatrick adds that he found Sennheiser “to be rather shallow and uninteresting as a person.”

Yet a year later he sought, unsuccessfully, to have Sennheiser supervise his doctoral thesis. He failed because he was unable to articulate his ideas in a comprehensive manner (which, the author notes, was a lifelong problem). To add insult to injury, he discovered that Sennheiser didn’t actually like him — news that apparently surprised and hurt him. A small group of colleagues seem to have seen him as a genius, “while others — probably the majority — ranked him lower or simply couldn’t understand him, and that disparity of reactions worried him.”

His personal life was equally contradictory. He was very good company, attractive to women, charming and personable. He loved classical music but was also an excellent pole-vaulter. He had been married twice before his marriage to Fitzpatrick, living with each of his wives for twenty years before the relationships ended in divorce. His marriage to Fitzpatrick lasted ten years, until his death in 1999.

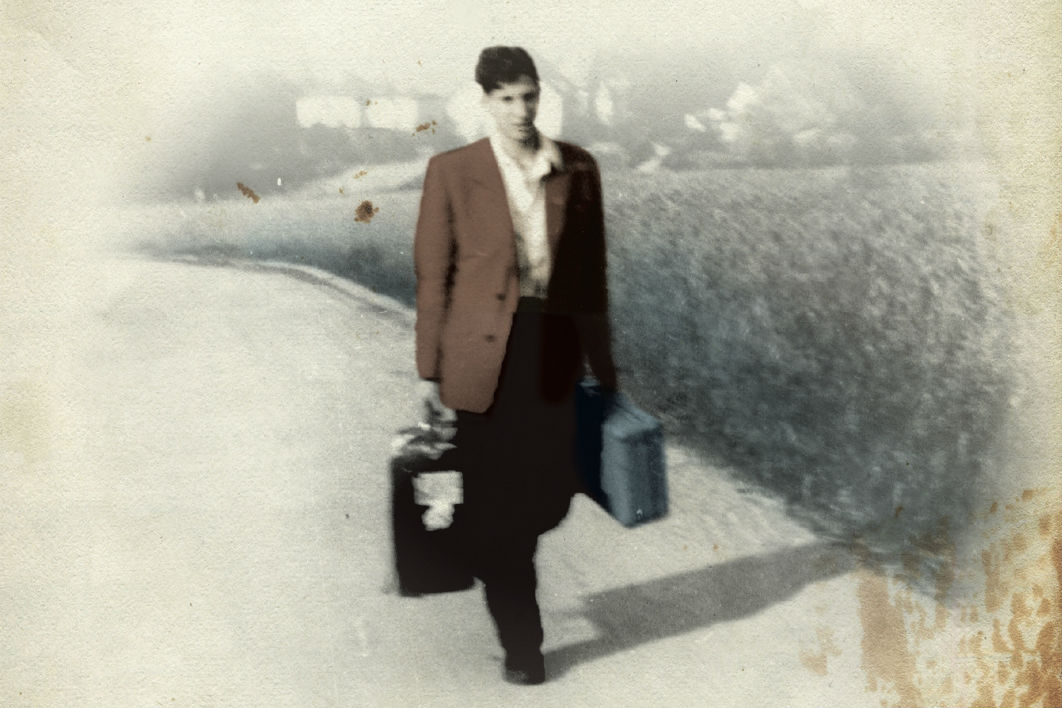

Fitzpatrick had always felt that Mischka had an inner personality that she did not have access to while he lived. After his death she came across the documents, letters, notes and photos that revealed at least some of that personality and became the foundation of this book. In her first and last chapters — for me, the book’s highlights — she provides a fascinating commentary on the book and a critical assessment of its limitations. She doesn’t shy away from writing about the dark aspects of her husband’s life and behaviour.

While she set out to write only about her husband’s early life, she found this impossible to do without examining Olga’s tremendous influence. Olga was melodramatic, prone to self-pity yet remarkably resilient, and not averse to conniving, lying about her age or exaggerating her own singularity. And we can’t avoid concluding that she played a large role in creating Mischka’s fraught personality.

She was not convinced, for example, that Mischka’s first wife, Helga, really knew what kind of man she had married. She wrote to her:

He is an exceptional man. He does not belong to those with a well-balanced nature, who systematically work towards a goal, cool and considerate. He is a pure artist (his science is pure art) and as such, sensitive, subject to moods, eruptively creative. He needs a wife who believes in him and his abilities… It lies in your hands to give the world a great man.

This intense mother–son relationship has definite echoes of D.H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers and even of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, and to my mind Fitzpatrick’s account of Mischka and Olga is every bit as compelling. They emerge as real people with both admirable and flawed characteristics. Each lived their early to middle lives in incredibly turbulent times that influenced their actions as well as their personalities. The author makes their lives vivid, while remaining aware of the particularity of her project:

This is a historian’s book, not a memoir, but it’s also a wife’s book about her husband. There are tensions between those two purposes… I hope they turn out to be the kind of tensions that make things more interesting rather than the spoiling kind.

For this reader, Mischka’s War is undoubtedly enhanced by those tensions. ●