The website pepysdiary.com has been posting daily entries from Samuel Pepys’s 1660s diary since 2003, each entry inviting comments from readers. Since the diary itself ran for nine years, we are in the third cycle of online entries and accumulated comments. As Kate Loveman remarks in her new book, The Strange History of Samuel Pepys’s Diary, the website continues many traditions recurrent in the diary’s 350-year existence: educating readers about Britain’s Restoration era, shocking readers with the values of different times, making readers feel a personal connection to Pepys.

Loveman suggests that the website also continues some less apparent traditions. Misremembering the British past. Inducing each generation to think they are finding the only true and enduring shocks in the work. Passing off a translated version of the diary as the unadulterated text Pepys composed.

In her lively, innovative analysis, Loveman ranges over all these traditions, striding steadily from 1 January 1660, when Pepys began his diary, via its posthumous deposit in Magdalene College, Cambridge in 1724, to its various editions and spin-offs up to the present day.

Throughout, she maintains that Pepys’s diary has always been “a gateway drug to history” for the English-speaking world. It has been a portal to an empirical sense of history, outlining the contours of the early Restoration period — especially the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666. It has provoked a philosophical approach to history, igniting debate between those who judge the past by their own values and those who (say they) do not. Finally, it has pushed readers into an evaluative or critical sense of history, generating discussions about whether the actions of kings count more or less than those of ordinary people (like Pepys).

All these modes of history are invoked in Loveman’s recounting of the traditions that have coloured the curious afterlife of one man’s six-volume private journal.

Samuel Pepys (1633–1703) was born the son of a humble tailor, though he had influential relatives. In 1655 his cousin obtained a minor clerkship for him in Oliver Cromwell’s republican government. After Cromwell died in 1658, the same cousin — a man who was instrumental in restoring the ousted Stuart monarchy to power — arranged a position for Pepys on the Navy Board. Seamlessly transforming from republican servant to loyal monarchist, Pepys eventually rose to become Secretary of the Admiralty.

Pepys kept his diary for the first nine years of Charles II’s restored reign. The commitment turned into an obsession, a vital outlet for a man gripped by a need to impose an orderly narrative onto chaos and an intense curiosity about power and sex. When he gave up the diary in 1669, believing it was damaging his eyesight, he grieved that doing so was “almost as much as to see myself go into the grave.”

No one else read the diary during Pepys’s lifetime. He knew that its revelations about the decadence of court life could get him fired, that its confessions about extramarital affairs would ruin his marriage, and that its exposés of Charles II’s debauchery might see him executed. To ensure privacy Pepys used a confusing combination of shorthand, longhand and foreign language.

He always intended for later generations to read the diary, though, primarily to secure his reputation as an efficient and effective civil servant of a burgeoning great state. Among the 3000 volumes he left to Magdalene College were not only the diary to testify to his work during the early years but also records of his administration during the rest of the old Stuart era.

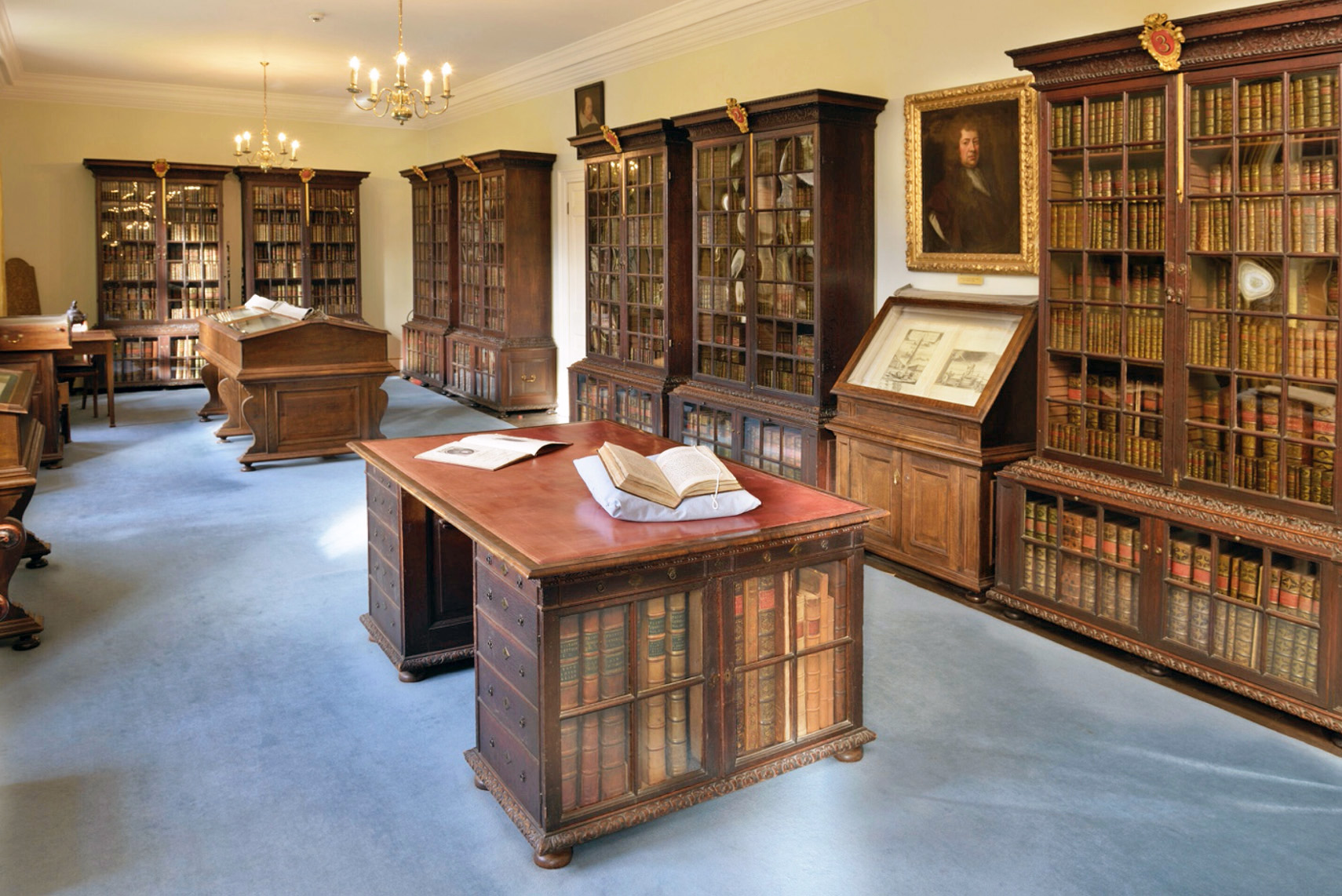

Pepys’s Library, including his famous diary, left to Magdalene College, Cambridge.

Even before Pepys died, though, he must have known that his hope of posthumous admiration was uncertain. He’d not well survived the transition in 1688 from the last old Stuart king, James II, to the new constitutional order of King William III. Although he remained firmly Protestant, Pepys was associated too closely with the growing Catholicism of James II, which had prompted the transition in the first place. He was arrested twice in 1689 on charges of treason against William III. He was never convicted but he retired from all offices and spent his final years worrying about how history might recall him.

For the next century Pepys’s worries were more than justified. His legacy was mostly ignored during a period so focused on moving away from an absolutist monarchy that its first impulse was to pretend it never existed.

He fared better in the nineteenth century. As their empire began to soar, Britons became interested in reimagining the past as a process of nation building. When Pepys’s diary was finally published (heavily abridged) in 1825, though, it was deployed not as a celebration of the Restoration era but as proof of how far Britain had come. The founding Whig historian Thomas Macaulay used it extensively to condemn the excesses of the previous order. He argued that Pepys’s diary was a litany of past “crimes and follies” that should motivate readers to consolidate parliamentary reform and a strict sense of Protestant morality.

Early twentieth-century readers focused more on the events Pepys recounted than on the political scene — a sign perhaps that Macaulay’s vision had panned out so well they now assumed parliamentary government and Protestant culture were timeless aspects of the national character. Haunted by world wars, these readers sought comfort by reading about how other Britons had endured plague and fire. One reader wrote that the French novelist Honoré de Balzac is “too depressing” but Pepys keeps her “cheerful.” Another felt that only Pepys had the words to describe what it felt like to live through the Blitz.

Postwar, Pepys’s diary was re-read again. Editions by now included more (though not all) of the lewd scenes earlier omitted. The attraction became neither politics nor personal endurance but instead Pepys’s cultural world of bawdiness. A BBC drama series of the diary characterised Pepys as a roguish if competent man about town while The Benny Hill Show made him out to be a “naughty” eccentric. A few generations on, it is interesting to see the beginnings of a more inward-facing, “Little England” mentality.

For most of those years no reader was absorbing the entire text of Pepys’s diary, for a full and unabridged edition didn’t appear until 1976.

Kate Loveman is most insightful when narrating the tortuous path from Pepys’s composition to final publication. The first of the five main editions, published in 1825 in two volumes, omitted most references to Pepys’s daily life and all but one hint of sexual misconduct, publishing just a quarter of Pepys’s words. A second edition in the 1840s expanded to include around 40 per cent of the diary. The 1870s edition saw around 80 per cent published, and Henry Wheatley’s 1899 edition represented everything except “a few passages which cannot possibly be printed.” Only in 1976 did the Cambridge historian Robert Latham and the UCLA literary professor William Matthew finally produce a full scholarly edition in eleven volumes.

Why such a long haul? What couldn’t possibly be printed for so long? Loveman shows how the definition and management of what is shocking has changed over time. The 1825 editors not only censored Pepys’s sexual behaviour but also tempered the raucous actions of his colleagues and friends. The women whom Pepys called “whores,” for example, were turned into “mistresses,” and the courtiers whom Pepys had running around with “arses bare” were now “almost naked.”

The 1840s editors allowed Pepys to be slightly less socially reputable, permitting him to drink and make poor decisions. But he was still not afforded any sexual license, and in the aftermath of Charles II’s coronation, as an example of his public behaviour, he was said to “vomitt” rather than wake up “wet with my spewing.”

The 1870s editors cared measurably less about Pepys’s respectability but were still highly cautious about sex. They allowed him one of his vastly numerous affairs, though when his wife caught him they had him say that he was “embracing the girl. I was at a wonderful loss upon it, and I endeavoured to put it off.” What Pepys actually wrote was that he was found “imbracing the girl with my hand under her skirts; and endeed, I was with my hand in her cunny. I was at a wonderful loss upon it, and the girl also.” Pepys was finally granted a sexuality, but it had to be a tame one and cloaked in shame if performed outside marriage.

Even Wheatley, who published nearly everything, presented Pepys “embracing the girl… I was at a wonderful loss upon it, and the girle also.” Adding in an ellipsis (and an extra olde worlde e) told the reader a bit more about Pepys, though nothing explicit.

By the 1950s, scholars at least were fed up. The Magdalene College librarian complained that Wheatley’s addition of that ellipsis had actually made readers “put a worse construction on Pepys’s famous affair with Deb than the full account justified.” Most fellows at Magdalene, including C.S. Lewis, agreed. The sticking point now was not so much fears of readers’ meaning-making but a more prosaic fear of the law. Editors were bound by the 1857 Obscene Publications Act’s provision for a work to be destroyed if the material tended “to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences.”

Eventually, in 1959, the law changed to exempt material that was for “the public good.” At length, Magdalene decided to go ahead, and the result was Latham and Matthews’s unexpurgated version.

Loveman’s tale of gradually lessening censorship is told subtly. She narrates a Britain inflexible about unrespectable and sexual behaviour gradually becoming a place more relaxed about one and then, at length, about the other. The temptation is strong to imagine that today, at the end of the tale, we have arrived at a nirvana of toleration, quietly mocking readers before us who not only had silly values but were also dumb enough to judge the past by them.

Loveman refuses this conclusion. Her last chapter provides a pretty convincing reading of Pepys as both a sexual assailant and a slave owner — two identities earlier readers seemed not even to notice but which agitate modern people very much. On assault, she provides at least six examples, including when Pepys had, with a girl under fourteen, “great pleasure [by] touching her thing with my thing and doing the orgasm” and when he “tried to do [to Mrs Bagwell] what I would, and against her will I did it.” On the issue of slaves, Loveman highlights at least two men owned by Pepys. The first of his “Black-Boys” he sold for some sherry and chocolate. Later, he was so angry with another “Negroe” for bad housekeeping that he ordered him to be “disposed” of on a ship and “kept on Hard Meat” till he arrived at a plantation.

Loveman’s point is not to advocate censoring Pepys, as past editors had, or even to cancel him, which is the modern preference to censorship. But she does wish to show that our revulsion at this evidence was probably similar to what earlier readers experienced, though the sources of dismay are different. Every reader judges the past according to values that each believes so essential they surpass history. The answer to judgement should be neither censorship nor cancellation. The best response — as I interpret Loveman to be saying anyway — is to recognise and understand changes in morality, and to realise that doing so constitutes the deepest work of philosophical history.

The final Pepys tradition parsed by Loveman concerns the readers’ sense of having an intimate and direct connection to the diarist. Commentators on pepysdiary.com know the feeling well. Almost all of them call him Sam. In 2012, when the first cycle of the diary ended, one remarked that “Sam has been truly alive for us in ‘real time.’” Another who had just experienced a bushfire observed himself “watching my neighbours’ house burn down on TV with the same surreal sense… that Sam must have felt when he saw the pigeons fall [during the Great Fire].” During the Covid-19 pandemic, several reported that reading Pepys made them “better prepared to talk about the realities of quarantine.”

It’s an experience that can be traced backwards through the entire timeline of Pepys’s diary. In 1914, for instance, a reader noted that no man “knows any of his fellows… as well as all of us know Pepys.” Sixty years before that, another insisted everyone “is taken into [Pepys’s] innermost soul.”

For sure, Pepys’s personable style accounts for much of this response. But Loveman shows that it also reflects a belief that readers have access to Pepys’s raw, unfiltered thoughts. Most assume Pepys wrote the original in code so no one else could read it, and thus also assume Pepys had no reason to polish, massage or otherwise fake his reactions. Loveman’s most original contribution is to explode this myth.

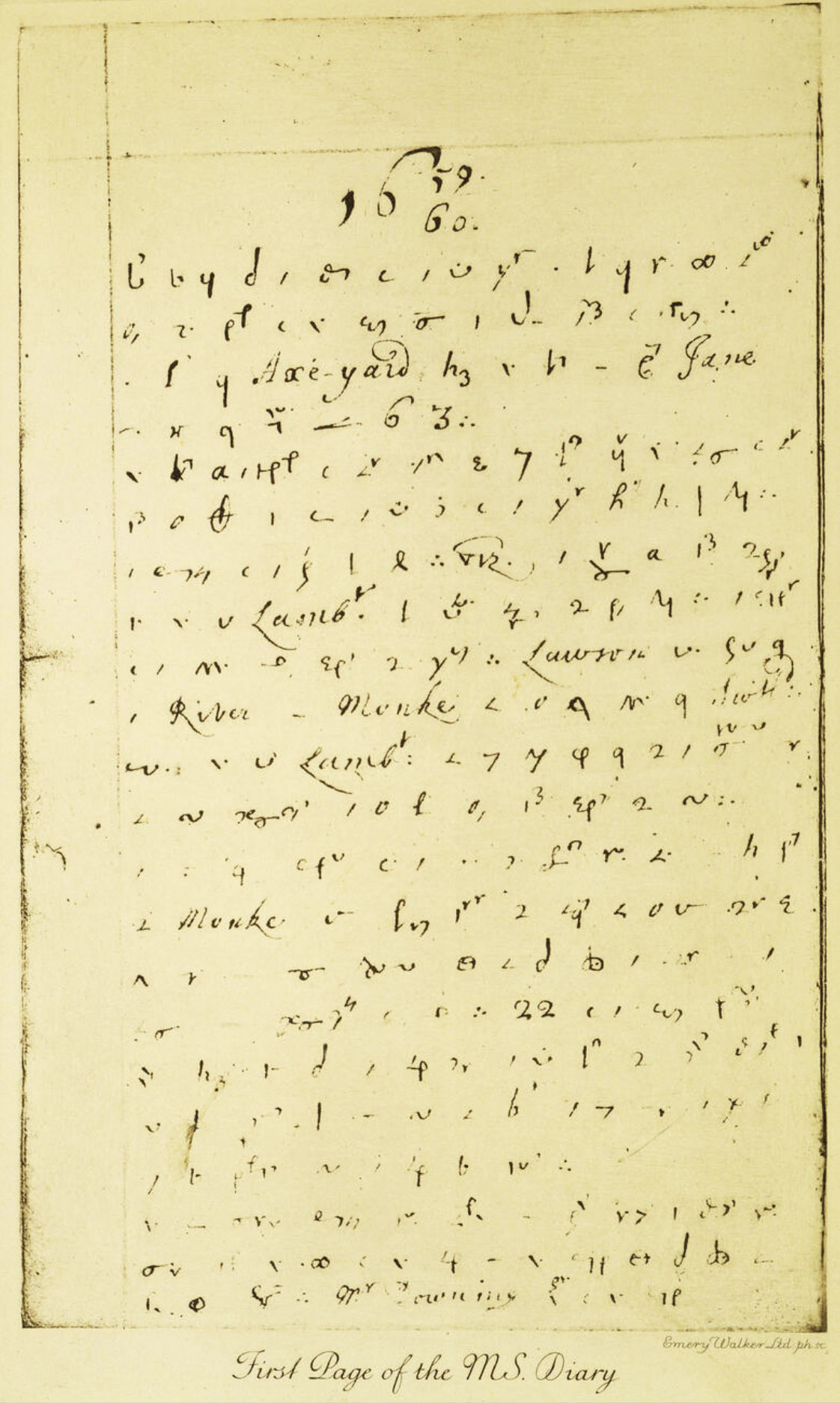

The opening page of Pepys’s coded diary.

The agreed wisdom is that the diary’s code was first broken by a Cambridge undergraduate called John Smith, who worked on the diary for three years. Smith never explained how he cracked it, leaving most to deduce it was solely from his genius. No conventional shorthand manual matched Pepys’s method. But Loveman has found that very early on in his transcription Smith was comparing Pepys’s markings with those uniquely found in Thomas Shelton’s obscure Tachygraphy (1635). Moreover, a copy of Shelton’s guide was included in the 3000 volumes Pepys left for Magdalene. Pepys did anticipate readers, but just not during his own lifetime.

Loveman further shows that the adulterations to Pepys began with Smith himself. He imposed his own punctuation and frequently omitted things he found “objectionable.” Very few people after Smith ever learned the code. This means that successive formal editors have only ever worked with Smith’s version, and we have already seen how much they imposed their views. As Loveman writes, we tend to think of Pepys’s code as “a kind of cover… which has to be removed to expose the original meaning in English. Instead, the reverse is true. The shorthand is the original text.” If anyone has direct access to Pepys (and who can say what that is if he always wrote for an audience) then it includes only the handful of people living today, including Loveman, who can understand his language.

Unfiltered or not, the diary’s personableness has nonetheless had an important effect on how readers over the centuries have evaluated what they are learning, or judging, about the past. Even in the earliest edition, slashed of most quotidian references, readers were prompted to consider what the revelations of a commoner — like them— were adding to history. Walter Scott decided they were treasures to “antiquaries” at least, if not historians proper. That is, they provided critical insight into past leisure activities, crime worlds and superstitions but perhaps not into what truly generated change over time.

Later generations, less wedded to a division between antiquarianism and history, felt that Pepys’s anecdotes of the everyday worked at least to “enliven history”: they may not constitute the real thing but they made the real thing more palatable.

By the 1940s, some readers were wondering if Pepys’s everyday world was not in fact more real than the rarefied world of high politics. These were often readers who were taking part at the same time in the nationwide Mass Observation research project of recording daily life. One said she recorded because her details “should be very interesting to posterity in the way the Samuel Pepys diary is.” Another feared that her entries were “trivial stuff” compared to Pepys’s but she still recorded for “historians who may write in the future.”

The question of authenticity in Pepys’s text is more complex than we have till now believed. But the way the diary projects a sense of authentic access has all the same moved readers to profound meditations about the role of ordinary people in creating the history of their world.

From learning about what happened in the past, to thinking through the meaning of the past, to wrestling with what or who made the past: Samuel Pepys’s famous diary has indeed always been an enticement to the biggest issues of historical practice. “And so,” as the man himself would say, may it remain into the future. •

The Strange History of Samuel Pepys’s Diary

By Kate Loveman | Cambridge University Press | $42.99 | 237 pages