The Crime of Not Knowing Your Crime: Ric Throssell against ASIO

By Karen Throssell | Interventions | $34 | 344 pages

“Dad was famously close to his mother,” writes Karen Throssell, “so close that, according to ASIO, you couldn’t distinguish between them.” So close, too, that he considered calling his autobiography The Man Who Had a Mother rather than My Father’s Son, the title he eventually decided on.

This is the relationship that lies at the heart of this new book by his daughter, Karen Throssell, which explores the predicament of the son who had a loving relationship with his mother, the novelist Katharine Susannah Prichard, but whose professional life as an Australian diplomat was dogged by cold war suspicion of her political views. Prichard had been a founding member of the Communist Party of Australia in 1920, two years before her son was born.

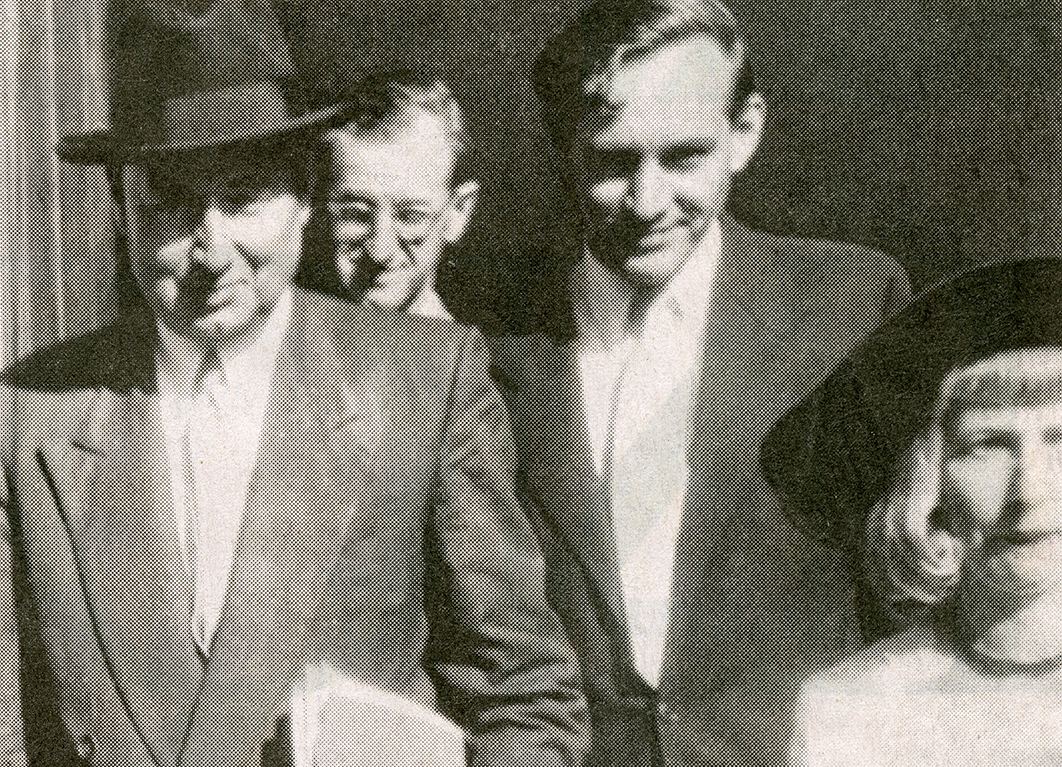

The Crime of Not Knowing Your Crime, ten years in the making, is compelling and timely. As a poet, academic researcher, daughter and granddaughter, Throssell employs an innovative mix of biography, memoir, poetry and history to recount the shadowy, Kafkaesque persecution of her father by ASIO and conservative political forces, including the press. In a collage made up of 103 “items,” she combines poetry and prose, letters, articles, photographs and quotes, all laid out like an ASIO dossier, complete with white-on-black quotes from Ric Throssell’s autobiography that resemble redactions uncovered for the reader. (It’s a most impressive job by graphic designer Viktoria Ivanova.) Also included is an informative contextual essay by cold war historian Phillip Deery.

The richness of the main text is achieved not via a conventional narrative arc, but by letting these varied voices, visual images and writing styles rub up against each other, almost like Brechtian dialectical theatre transferred to the page.

In the opening sentence we read the unembellished fact that Ric Throssell died from an overdose of Doloxene in 1999 at the age of seventy-six. A few pages later, Item #6, “The Old King,” is a moving poem about the death of the thespian Ric, who played most of Shakespeare’s heroes at the Canberra Rep theatre, accompanied by a photograph of him in the role of Macbeth. The poem, which gives us a sense of the impact of his death on his family, finishes:

The old king is gone, our father, our king

And whilst he would have cried that

“Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,”

We too stood on that stage

Now empty, save for the heartache.

Still later, we learn that Throssell died in a suicide pact with his beloved wife Dorothy (Dodie) after she was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumour.

The central theme of the book — the scapegoating of Ric Throssell during the volatile cold war years in Australia — gradually emerges. We read of his disastrous year in Moscow, aged twenty-three, working for Australia’s external affairs department; of the codename “Ferro” he had been given in two of the cables decrypted by the US-based code-breaking Venona Project; of the convoluted process by which he was “named” by KGB defector Vladimir Petrov; and of his (and Dorothy’s) appearance before the Menzies government’s royal commission on espionage in 1955, where both were acquitted.

The Crime of Not Knowing Your Crime documents the years in which Throssell was repeatedly passed over for promotion, with “security considerations” blocking his previous career path within External Affairs. When his case finally attracted high-level attention — from Gough Whitlam’s attorney-general Lionel Murphy — the government was dismissed before any real progress was made.

The book also lays out the press attacks on Throssell after the release of the Venona transcripts in 1996, with Item #58 recording a contrasting favourable article by Norman Abjorensen in the Canberra Times: “The vendetta against now-retired diplomat Ric Throssell is a sad reflection on our reputation for fairness… Given the amount of attention devoted to Prichard and Throssell it is revealing to what extent the spooks were spooked by the Communist writer.” The attacks continued even years after his death.

Writing sometimes from a child’s perspective, Karen Throssell reflects on important events in her parents’ lives. When she was seven years old, she was sent off to stay with her aunt and uncle in the Upper Yarra outside Melbourne while her parents, mysteriously, had to “go to Sydney.” As the royal commission on espionage dragged on and the weeks became months, her joy at playing in the bush with her cousins turned to fear that she had been abandoned.

Karen also builds compassionate pen pictures of Ric as a father, of her mother, and of her famous grandmother. Ric had a shack in the back garden of their quarter-acre Canberra block to which he would repair for hours each weekend to write, “having the odd break to chop wood for the ‘Wonderheat’ or to tend the veggie patch.” A series of poems reveals Karen’s shy, beautiful and fiercely intelligent mother:

Dorothy Jordan, snow-silent, owl-wise

blending with shadows, cowering from crowds.

She found her soul-mate: mind and heart.

But this man had a mother — the red witch of the west.

This man had a mother —

contagious they said.

The “red witch of the west” also has a series of Items devoted to her. In one, she is remembered as “My Fairy Godmother”; there are quotes from her autobiography; and one of the most poignant poems in the book, “Postcards from Russia,” weaves in excerpts from Prichard’s letters home during her 1933 trip:

Dearest Jim [Hugo] and little Ric

I thought you’d like to know I’m eating well!

Breakfast at the stolovyah

Meat rissoles, blenchki with thick Siberian honey.

But I do miss your porridge my love

And breakfast all together…

It was while Prichard was in Russia that her husband Hugo Throssell, a Victoria Cross recipient worn down by the Depression and in financial straits, killed himself.

The Crime of Not Knowing Your Crime is a book to savour, return to and reflect on. It is also chillingly timely as the world moves closer to a new cold war, drawn along different but no less dangerous lines. In Phillip Deery’s words, “ASIO has acquired a higher degree of political respectability and moral legitimacy,” with more sweeping powers and a massive new Canberra building, nicknamed Lubyanka by the Lake. It is more important than ever that the secretive machinations of its tawdry past should not be forgotten. •