PIX was a phenomenon, a magazine that brought images of ordinary and not-so-ordinary life into homes and workplaces, documenting Australia and the wider world — sometimes brutally, sometimes idealistically — and enjoying what strikes us now as a massive circulation. By 1940, only two years from its launch, the country’s first all-picture magazine was reaching an astonishing 682,500 readers out of a population of some seven million.

The current State Library of NSW exhibition “PIX: The Magazine that Changed Everything (1938–1972)” also forms the basis of a splendid book about the phenomenon, PIX: The Magazine that Told Australia’s Story. The change in subtitle during the journey from exhibition to book — from “the magazine that changed everything” to “the magazine that told Australia’s story” — subtle though it is, reflects a growing institutional awareness of the importance of photographs as historical documents.

State librarian Caroline Butler-Bowdon highlights this awareness in her preface to the book, drawing particular attention to the library’s role in collecting photographs, specifically those that document “life in New South Wales and across the nation.” It is part, she says, of an “ongoing institutional commitment to photography,” to expanding the collection and increasing its accessibility. As part of that commitment, all 167,000 photographs in the PIX archive have been digitised and are viewable online.

The rapid digitisation of its photography collections — and specifically of collections of documentary photography — being undertaken by the State Library is matched by similar initiatives in other public institutions in Australia and elsewhere. It is part of a renewed recognition of the value of visual history and the contribution it can make to our understanding of the past. (A recent study day offered by the State Library, “PIX Magazine in Research,” is typical of broader institutional encouragement of the public to explore and make use of photographic collections.)

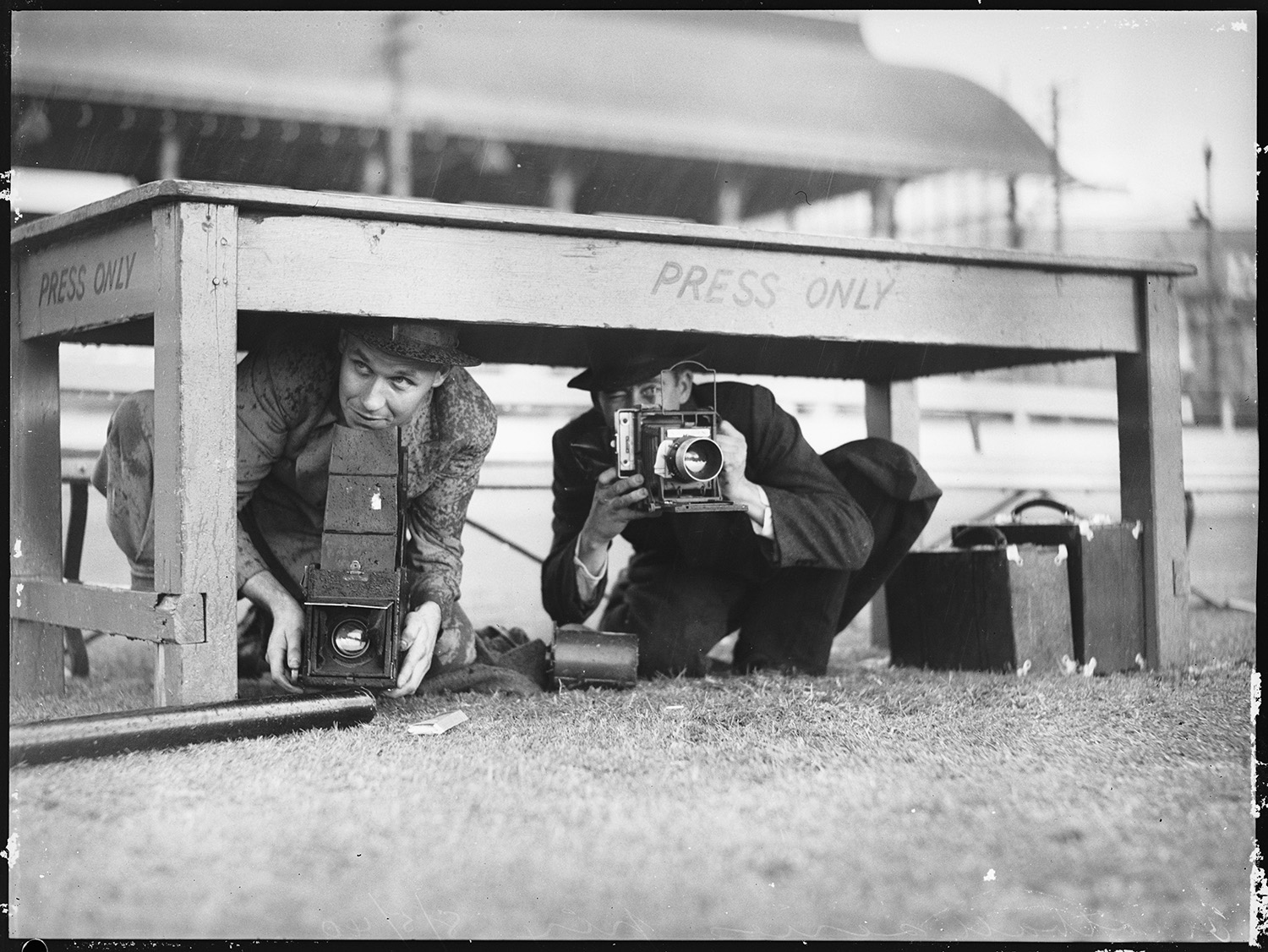

Ray Olson’s photo of fellow press photographers sheltering from the rain at a football match in 1940. State Library of NSW

It can’t be accidental that this renewed institutional emphasis on photography as an historical resource — involving in many cases significant financial commitment — comes at a time when the practice of photography is pulling away from a direct relationship with history and from the status it has enjoyed as a medium of record.

From generative or AI-assisted photography to deep-fakes, our faith in photography to record something that happened is being rapidly eroded. PIX photographs, and others like them, thus exert a double appeal to nostalgia — not only for the events and the lives that they capture, but for the broader fact that they belong to a time when a photograph could, more or less, be trusted.

Some will argue that photography could never be trusted, that it has always been subject to instances of manipulation and falsification. True, but not so true that it undermines photography’s hugely significant role as a medium of record, a role that, according to the pessimists, is under threat. In the words of photographer and theoretician Joan Fontcuberta, there is a widespread fear that “photorealistic images made with AI will destroy the credibility of documentary photography.”

The renewed institutional commitment to photographic collections represents a response to that fear. It is an expression of confidence in the continuing value of past photography as a documentary record, however much uncertainty there may be over the direction being taken into the post-photographic future.

Notwithstanding their documentary status, PIX photographs don’t always present themselves simply as unmediated records of events — rather they capture scenes that have clearly been plotted and prepared, or to some extent re-enacted. PIX photography was by its own lights in the business of representation as well as documentation. Representation in the form of youth, energy, fortitude, effort, resilience — in short, of a particular idea of Australianness.

Accordingly, there is a deliberateness to many of these photographs, with the preparation that went into the making of the image visible in the final result. The voice of the cameraman as director can be imagined, rehearsing the scene, placing the essential components. Pose, lighting, camera angle all work together to dramatise the subject, and the evident discomfort or self-consciousness of the people being photographed will often contrast with the sophistication of the camerawork.

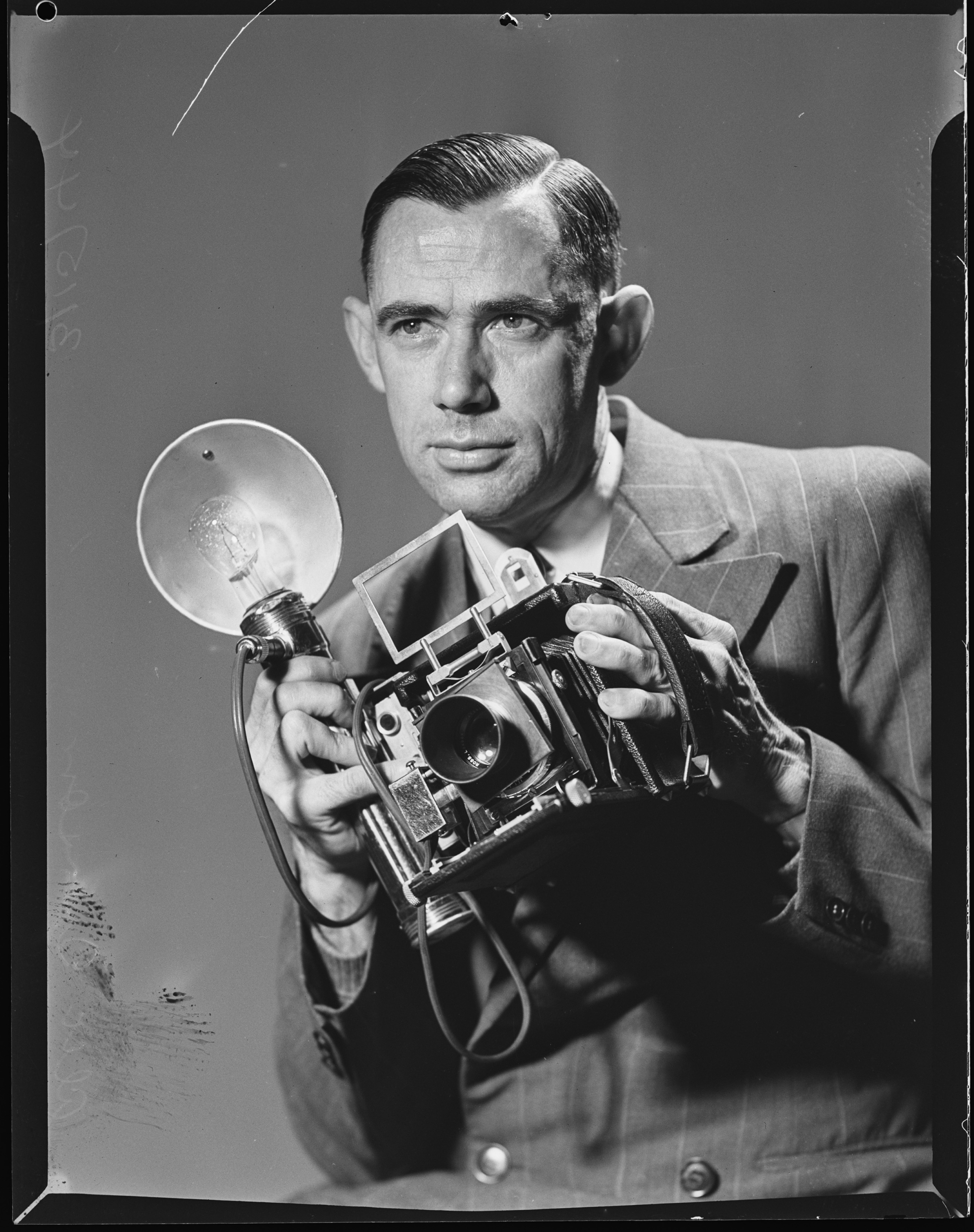

PIX photographer Alec Iverson photographed in 1944. State Library of NSW

This deliberateness of composition leant the camera operator a certain implied visibility. But photographers also appear directly, as subjects. Many pictures in the archive of these glamorous and relatively novel professionals — instructing models, checking lighting, peering into viewfinders and lining up shots — also appear in the archives.

To show the workings of photography in this way served to further glamourise rather than demystify. From time to time, readers of the magazine were invited to submit their own photographs, though it is not clear how many ended up crossing the barrier from viewer to contributor. Photography as a profession offered the promise of an exciting world, full of potential subjects waiting to be photographed.

Many young photographers who entered the profession during the forties and fifties would have felt much as the celebrated Indigenous photographer Mervyn Bishop — himself the subject of an exhibition currently at the State Library of NSW and an accompanying biography, Black, White and Colour, by Tim Dobbyn. “I loved the smell of the dark room and watching the image come up in the developer,” recalled Bishop. “It was magical.”

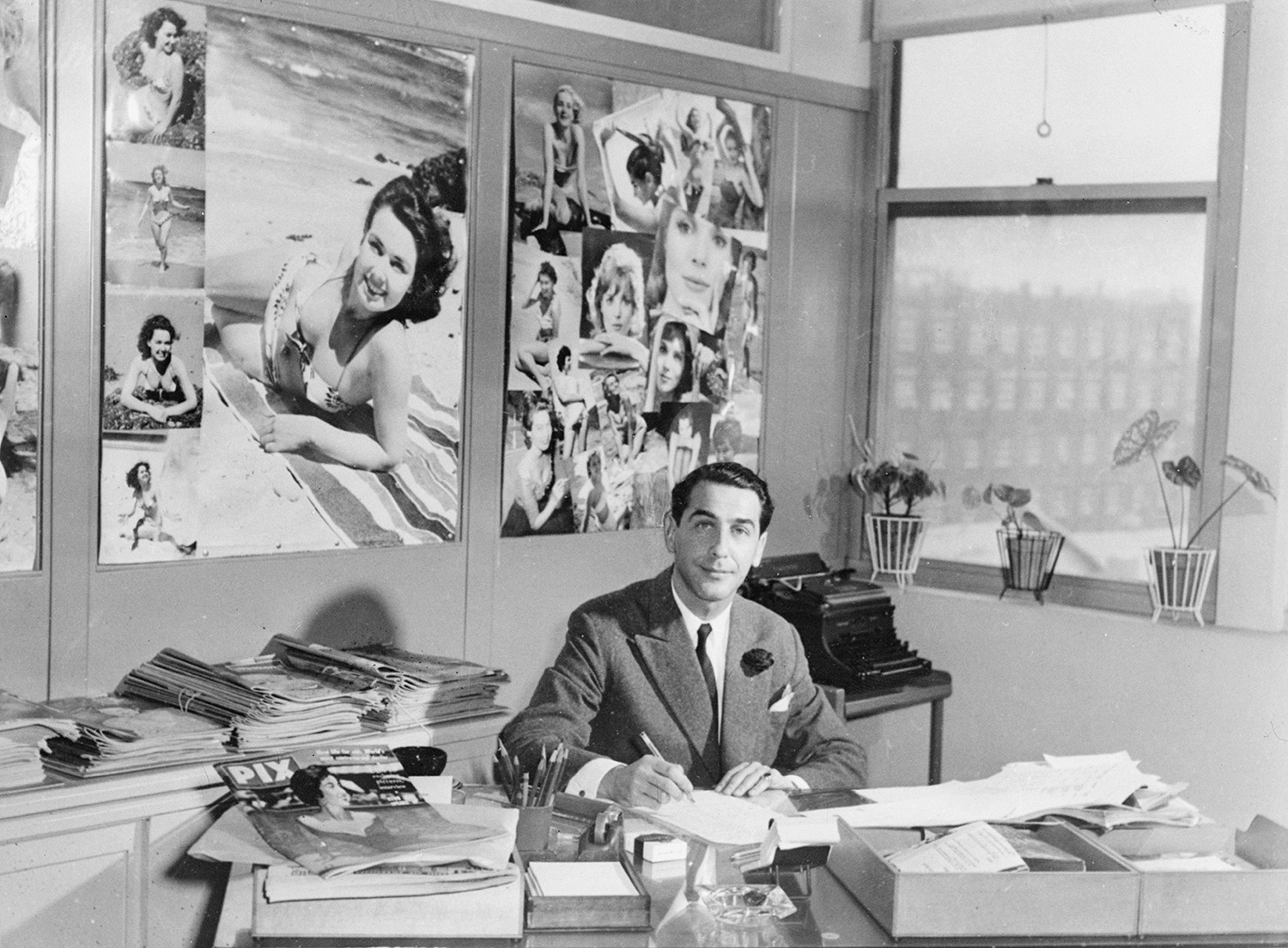

From the beginning, in what must have seemed like a risky marketing strategy at the time, PIX pitched itself as a more satisfying alternative to film. While film (the film of life, to be grand about it) rushes by in a continuous flow, the photograph pauses that flow and allows for a much deeper, reflective experience. “PIX’s first advertising tagline,” the book’s editor Margot Riley notes, “compared the magazine’s visual impact to the cinematic newsreel,” a comparison that was soon refined to emphasise the differences rather than similarities between photography and film. A PIX photograph, it was claimed, “stops the action so you can study, examine, learn every detail and return again and again to these fascinating subjects.”

This high-minded appeal to the human impulse to study, examine and learn would have been interpreted by many subscribers to refer to the signature images of women sunbathing, or caught mid pirouette or plié, that were an essential component of every issue of the magazine. A splendidly staged photograph of the editor of PIX, taken in 1959, makes the deliberateness of this more down-to-earth appeal very clear. The editor, positioned importantly behind his desk, is himself caught mid-flight, in the act of signing an important-looking document, while fixed to the wall behind him are two larger than life collages of young women staring invitingly at the camera.

PIX editor O.A. Guth photographed in his office by Cec Lynch in November 1959. State Library of NSW

But glamour and glamourisation were only part of the story. Indeed, it is remarkable, scrolling through the digitised collection, to see how varied the subject matter of PIX photography could be, and in many cases how strikingly unglamorous. A photograph of a cane-cutter and his wife and young daughter, seated on packing crates to eat what seems to be their evening meal, has much of the art-directed quality that is a familiar hallmark of the magazine without detracting from the naturalness of the subjects and the unforced dignity they display in such basic conditions. Another image, of the same cane-cutter squeezed into a tin bath at the end of a working day, succeeds in capturing his essential dignity in less than dignified circumstances.

Ivan Ive’s photograph of the van Deest family in the Queensland canefields. State Library of NSW

The photographs of the cane-cutter and his family are part of a large series of images made on the Queensland canefields by the most prolific of PIX photographers, Ivan Ive, son of the pioneering Australian cinematographer Bert Ive. The curators of the PIX archive rightly single out the younger Ive not only for the quantity of his output but for its range and quality. He was both remarkably productive and impressively inventive.

One reason perhaps why Ive is not better known is that, partly by virtue of this flexibility, his work doesn’t display an easily identifiable photographic eye. His images can appear highly staged, almost to the point of manipulation, but he is also capable of a more frankly direct gaze, where his own implied role as stage designer is effaced rather than highlighted. He can be showily inventive and a bit cold, but also discreetly sympathetic, sometimes foregrounding technique and at other times subsuming it to the subject.

Ive, along with other PIX photographers, was quite willing to share some of his professional secrets. In a feature published in the magazine in February 1948 he shows how “photography can enter the realm of art,” demonstrating by means of a sequence of images how he gives an “ordinary photograph” of a model dressed in Renaissance style clothing the patina of “an Old Master.”

Ive is shown making another photograph, this time of a stippled screen he has borrowed from a newspaper blockmaker. He describes how he puts the two negatives together to create, from scratch, a painterly artefact. We see him (top photo) holding the stippled screen up to his eye to examine it more closely. The screen forms a frame around his head, a frame that also contains, in the background, a PIX pinup posted on the wall behind.

One of Ivan Ive’s “Old Master” photographs, published in PIX in 1947. State Library of NSW

In his wonderfully evocative series of seventeen photographs of a Greek Orthodox baptismal ceremony, taken in 1946, Ive displays his talent for capturing the human aspect of ceremonial occasions, in which formality combines smoothly with spontaneity. The image from this series reproduced in PIX: The Magazine that Told Australia’s Story, showing eleven-month-old Alexandra Cassimatis on the point of immersion, offers a deeply satisfying sense of composition without appearing, as PIX photographs can sometimes do, all too deliberately composed.

The image appears here as it did in the October 1946 issue of the magazine, where it has been cropped from the original. The original version of the photograph, which is viewable in its more expanded form in the digitised archive, takes in other members of the congregation, drawing the eye in several directions. The effect of the cropping is to tighten the sense of composition and to focus on the relationships among the principal figures — the priest, the godmother, the mother and baby, with a child, who we infer to be baby Alexandra’s brother, completing the quintet by resting his hand against his mother’s side and reaching up into the centre of the image.

Alexandra Cassimati’s baptism, photographed by Ivan Ive, as it appeared in PIX in September 1946. State Library of NSW

These figures, their hands combining with or gesturing towards one another in a complicated balletic pattern, frame the faces of the two women in the background, drawing these secondary figures into the overarching pattern and rendering them as participants rather than mere extras. The emphatic deliberateness of the cropping is one example of how the PIX archive repeatedly homes in on communal relationships, often by lining its human subjects up in rows or queues or semi-circles and thus making patterns out of people — rows of water-skiers or cyclists, of miners completing a shift or airline passengers waiting to board.

People are also linked to one another by their hats (prompting, in passing, the question of where mid-century portrait photography would have been without hats). Not only can the hat act as a frame or a defining characteristic, but it can also add humour or dignity or pathos to the face underneath. In group photographs, the hats can sometimes seem to be conducting a conversation of their own, mirroring and reinforcing the relationship between the wearers and adding a tongue in cheek element to an otherwise conventional composition.

“Girls knitting,” part of a series of photos of war workers published in 21 April 1941. State Library of NSW

A hat can also complicate and render more satisfying an individual portrait that might otherwise be more one dimensional in its impact. A PIX series on the Korean war includes individual portraits of diggers wearing a variety of military headgear, a hat or cap or helmet that seems in each case to act as an extension of an individual personality or suggest a refinement of mood. In one particularly effective image from this series, the jauntiness of the hat’s angle contrasts with the expression of shy vulnerability on the face of the soldier wearing it.

This combination of formality and humour, deliberateness and spontaneity, is characteristic of the PIX photo archive and reflects the way in which the magazine chose to “tell Australia’s story” as one of people from different backgrounds coming together with mutual goodwill, underpinned by a commitment to rules and order as a way of building social harmony. That idea of social order, perhaps unsurprisingly, involved fairly rigid notions of the respective roles of men and women in the national project.

Women were frequently portrayed as pinups or glamour models, or just as often in traditional domestic roles. But there are also, as Riley points out, pictures of women “exercising agency” in the workplace or in leisure pursuits, no doubt reflecting a certain confusion on the part of the photographers and the commissioning editors, almost exclusively male, as to quite where things were heading.

This confusion is reflected in images that play with the notion of role reversal. One photograph from the archive, taken on a beach in 1955, shows a woman in bathing costume riding a man with a very large turtle shell on his back. This image of a woman holding the reins, in what was presumably intended as an amusing representation of the absurdity of female empowerment, now has a distinctly unfunny air about it.

Another image, by frequent PIX contributor Cec Lynch, in a series from 1958 about equal pay for women, shows a family of three at breakfast time, the mother sitting at table and absorbed in what we assume to be the financial pages, while the father, standing by the kitchen bench and sporting an apron, bends over to wipe the remains of breakfast from his son’s chin. All three models look profoundly awkward, as if uncertain whether they have been cast in a straight drama or a comedy.

One of Cec Lynch’s “equal pay for women” photos published in April 1958. State Library of NSW

Kate Evans, in an essay that places this collection of PIX images in context, raises the question of what we can learn of the past through photographs, and of how far we can enter the world they represent. “You can see the cracked paint on exterior walls,” Evans remarks of a 1940s image of an inner-city street, “almost feel the texture of the hessian bags the people are leaning on.” “Almost” is the operative word here, signalling the built-in frustration that comes with looking, and with it the knowledge that looking may be as far as we can get.

Meanwhile, as institutions speed up the process of cataloguing and digitising the photographic past, an exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao by the generative artist and post-photographer Refik Anadol has just closed after breaking all attendance records. The exhibition, we are told, “reimagined the work of the museum’s architect, Frank Gehry” by creating huge, dynamic wall installations out of masses of visual data, using a “custom generative AI model constructed by Anadol from a dataset of over 32,147,692 images.”

In the two exhibitions, one a precisely focused exploration of photographs from a mid-century magazine archive, the other a flamboyant hoovering up of unimaginably large numbers of images to create something new, we see the two poles of how to approach and to understand the past by way of photographs. It remains to be seen whether these two approaches can ever be satisfyingly reconciled. •

PIX: The Magazine that Changed Everything

Curated by Margot Riley | State Library of NSW until 16 August 2026

PIX: The Magazine that Told Australia’s Story

Edited by Margot Riley | NewSouth | $50.99 | 336 pages