September 1, 1939: A Biography of a Poem

By Ian Sansom | 4th Estate | $39.99 | 352 pages

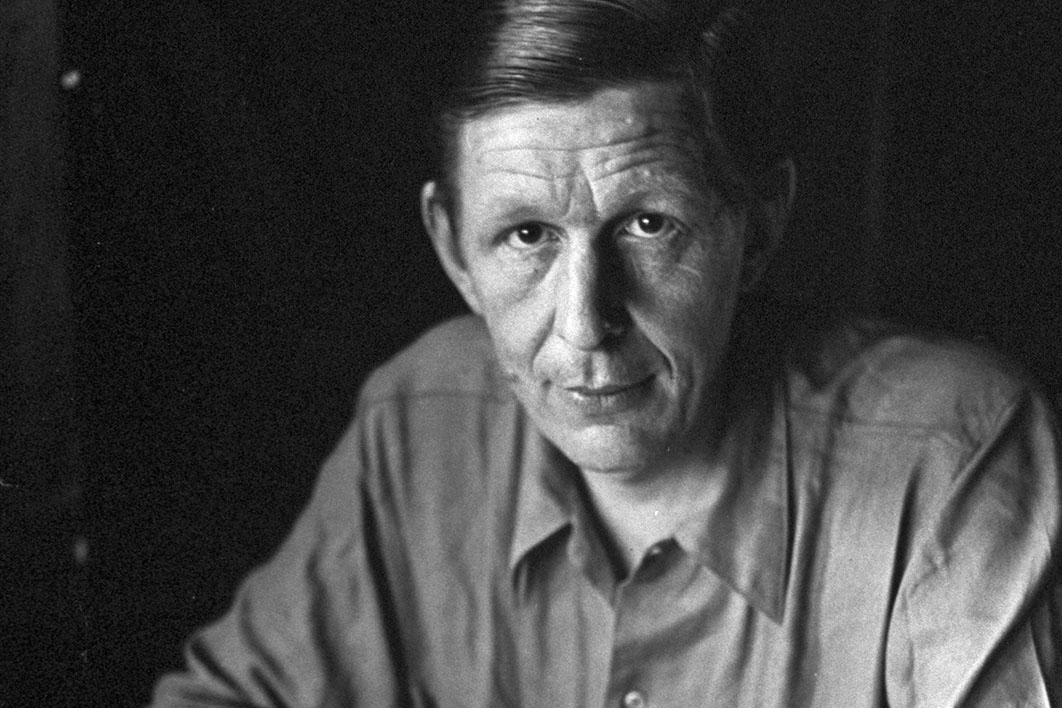

Ian Sansom likes to write on poems by W.H. Auden. Literally: he jots on them in pen and pencil, or covers them with Post-it notes, until the original is barely legible. By his own account he savours the illusion of intimacy, the imagined connection with a great poet.

An accumulation of notes also describes the structure of September 1, 1939. It is not really, as the jacket implies, an analysis of Auden’s great poem, written on news of war but later erased from his collected works because the poet was unhappy with its most-quoted line, “we must love each other or die.” Instead, Sansom gives us clippings, observations and digressions. His book is an extended run of Post-it notes about a poem. Along the way it is also an entertaining potted biography of Auden, and of Ian Sansom.

The personal narrative is Sansom’s motivation for writing. He tells us he invested twenty-five years in trying to finish this book, idolising Auden, writing a PhD about his work, teaching his poems. And what did he learn? That Ian Sansom is not, and never can be, Wystan Hugh Auden.

This could all be exasperating if you want to read about the poem rather than someone’s obsession. Yet I found it endearing: the tone is so personal, the regret so palpable, the sense of difference between genius and the rest of us captured so skilfully.

Those who know Sansom principally through his County Guides detective novels will spot parallels with his character Swanton Morley, the People’s Professor. Depending on the source, Morley is a poor man’s Huxley, Bertrand Russell or Trevelyan, but his popular columns in the Daily Herald find a vast audience among the curious if unlettered. Morley is often diverted to obscure tangents, finding connections or inventing whimsical diversions while his hapless assistant Stephen Sefton struggles to maintain order and reason.

Sansom might not be quite as prolific as the fictional professor, with his unending list of implausible book titles and improving pamphlets, but he shares Morley’s delight in pointless facts. Who remembers Lyndon Johnson using “we must love each other or die” in a 1964 campaign advertisement? Or Auden marrying Thomas Mann’s daughter in 1935 so she could escape the Nazis?

As Sansom rambles through the poem, in chapters organised around each stanza, we are invited to relish digressions that are often about the words Auden chose. Thus “ironic points of light” in the final stanza becomes an image for community — all irony lost — when Peggy Noonan writes a speech for George H.W. Bush.

Auden, of course, preferred rigour. He was notorious for re-editing published poems, and occasionally excising them entirely. Thus “Spain 1937” and “September 1, 1939” were both removed from the Auden catalogue by their author. The first had been criticised by George Orwell for a line about “the conscious acceptance of guilt in the necessary murder.” For Orwell there could never be a necessary murder, and in a biting comment he described Auden as “the kind of person who is always somewhere else when the trigger is pulled.” Auden acknowledged the power of the objection, first altered the offending line and then removing the poem entirely from future editions of his work.

In similar fashion, the poet came to regret “we must love each other or die.” His doubts extended to the whole poem, written swiftly on the news that German soldiers had invaded Poland. Again, he tried to rework the offending line, and then refused permission to reprint. When “September 1, 1939” last appeared with Auden’s permission, with other poems from the 1930s, the poet required a pointed editorial note: “Mr W.H. Auden considers these five poems to be trash which he is ashamed to have written.”

Despite this startling response to a poem so celebrated in its time, Sansom does not explore in depth the reasons for the poet’s antipathy. Auden’s fellow poet Joseph Brodsky stressed that “September 1, 1939” is neither contemptible nor insignificant. It was the first poem of the second world war, and the shame of the “low, dishonest decade” that led to conflict infuses the poem. Disgusted with himself and others in the bar where the poem is set, Auden seeks meaning when all political illusions have gone. He is, says Brodsky, “a stoic who prays” in the light of inhumanity.

Despite Auden’s verdict, “September 1, 1939” remains among his most memorable compositions. Not surprisingly, a poem that opens amid bad news in a dive on 52nd Street, the speaker “uncertain and afraid,” resonated across the city in the wake of the 9/11 attack on New York City.

This book is only secondarily about the poem that gives its title. It is really concerned with how an author of modest talent — which is to say all of us — can find any space in a world that also contains Auden. Along the way are amusing quotes and idiosyncratic admiration of a work of art that Ian Sansom insists, though not convincingly, is flawed. Why spend a quarter of a century, and more than 300 pages, explaining why Auden was right to doubt the poem but wrong to suppress its affirming flame? We are fortunate Sansom was not persuaded. •