Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Ella May McFadyen was a hardy woman, with a kind smile, pince-nez glasses and the musical voice of a skilled storyteller. Only fifteen when she began her career as a writer, the young Sydneysider recognised her vocation early. “There was something that I had to do,” she recalled in 1972. “I had to write.” Passionate and independent, she pursued an extraordinary career as a writer, editor and reviewer, driven by a lifelong love of nature and a delight in the magic of childhood.

Born in Petersham, Sydney, in 1887, McFadyen grew up on a small farm at Five Dock, in Sydney’s west, where the scent of buttercups and the hooting of mopokes instilled in her an early interest in the natural world. She did not attend the local school, instead finding companionship in her dolls and the books her father scattered thoughtfully around the family home. In a sign of what was to come, she often spent her time reading, sketching birds at the local museum, looking through old diaries and notebooks, and pretending to publish newspapers. After the family moved to Brisbane Water on the NSW Central Coast when she was fifteen, McFadyen became “confirmed in her habit of writing rhymes.” Not long afterwards, her photographs, poems, nature writings and short stories began appearing in print.

It was some years later, at the end of the first world war, that the opportunity of a lifetime reached the young writer by mail. W.R. Charlton, editor of the Sydney Mail, invited McFadyen to edit the paper’s new children’s page. It was her dream job, and for the next eighteen years she skilfully wove natural history, botany and poetry into her weekly two-page feature, crafting an extraordinary legacy as the fairy editor “Cinderella.”

By writing to many of her correspondents personally, as well as publishing their letters and contributions in her pages, McFadyen won the favour of her young readers and their parents. Thousands of children in Australia and abroad dipped their nibs in ink to write to her, sending letters, postcards, poems, stories, photographs, flowers and drawings. “One of the children called you ‘Queen of the Fairies,’” wrote one nine-year-old in 1922, “and now I always think of you as a fairy, as we are all so fond of reading and talking about you, and yet never see you. Are you really a fairy?” There was something enchanting about McFadyen. As another boy explained that same year, there was a “magic about the Page” that was enticing.

McFadyen had published photographs and verse before the first world war, but it was only after she started editing the children’s page that she really discovered herself as a writer. In the 1940s she published a number of popular children’s books, including Pegmen Tales (1946) and Pegmen Go Walkabout (1947) — a series of stories about a family of clothes pegs who sail down the floodwaters of the Macquarie River with a naughty monkey — and Little Dragons of the Never Never (1948), featuring the adventures of two little horned dragons from the centre of Australia.

Like many of her contemporaries, McFadyen created characters that were magical and fantastic, but they lived in distinctively Australian landscapes, under the kurrajong trees and in the swamps of the Never Never. Such settings reflected not only McFadyen’s involvement in the literary community of her day but also her lifelong passion for nature writing and bushcraft. As the editor of the Australian Women’s Digest wrote in 1949, McFadyen was the “high priestess” of camping, “a veritable walking encyclopedia on insects, birds and animals, with a slight bias towards eels and lizards.” Such was her knowledge of Australian lizards that Taronga Zoo and the Australian Museum sent several to her for care.

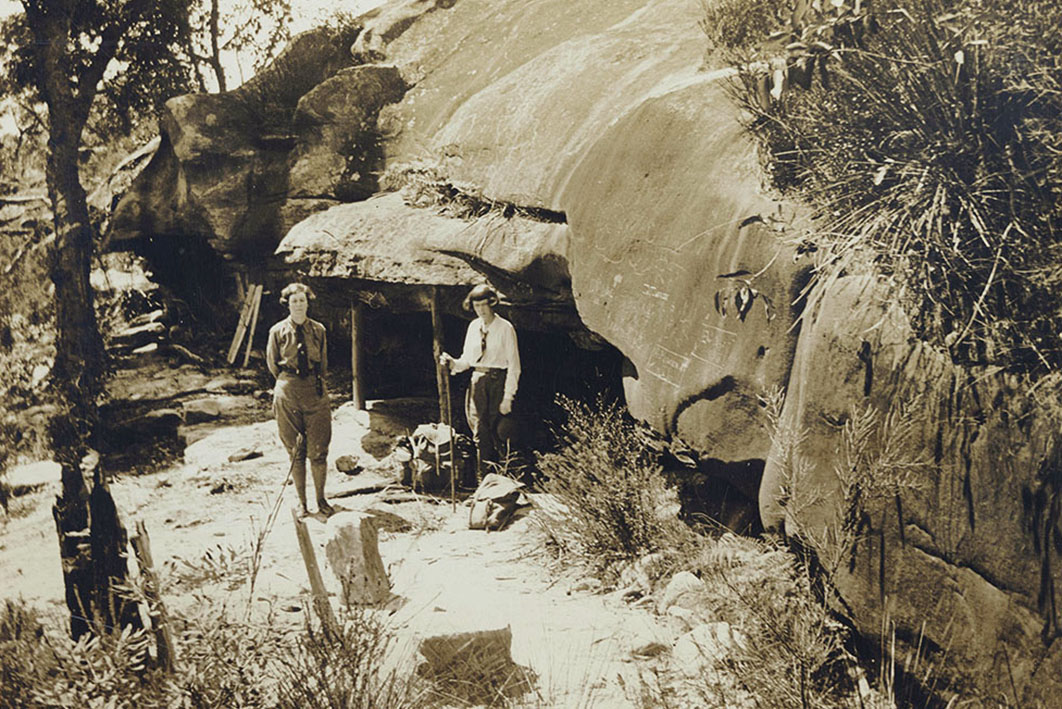

McFadyen’s love of Sydney and native wildlife was accompanied by a deep anxiety about urbanisation and environmental destruction. Her poetry, much of it published in newspapers and magazines, reflected a nostalgia for a landscape untouched by modernity, and she supported — and agitated for — bird and forest leagues, bushwalking clubs, sanctuaries and other environmental initiatives. Especially through her nature writings, photography and the Boomerang Walking Club — a bushwalking group for those senior members of the children’s page capable of walking no fewer than twenty miles a day — she encouraged children to become conservationists, teaching them about Aboriginal lore, bushcraft, and botanical and birdlife studies.

McFadyen continued writing for children in her later years. She made regular contributions to the School Magazine, Junior Red Cross Record, nature magazines such as Wild Life and Walkabout, and the Fairfax press. She gave talks on radio, at schools and to the Zoological Society, and contributed play scripts to the ABC’s Youth Education Department. She wrote Kookaburra Comedies (1950) and The Wishing Star (1956) and was a foundation member of the Society of Women Writers NSW. First recruited to the Junior Red Cross by Eleanor MacKinnon in 1914, she remained an active member all her life, later teaching “bushcraft, natural sketching and first aid” at their annual camps.

“Heaven without a gumtree, it’d be absurd,” wrote Ella McFadyen in 1972. Photo shows McFadyen and one of her little dragon friends, 1940–50s. State Library of New South Wales

Until 1973, McFadyen also used her growing confidence as a naturalist and children’s writer in her critical manuscript reviews for the publisher Angus and Robertson. To the dismay of many aspiring Australian authors, she took a particularly unforgiving view of stories with characters or narratives that she believed children would find crude or unconvincing. “Few children really care for baby talk, or ideas too carefully broken down for their consumption,” McFadyen noted in 1932. “Children’s stories, like their clothes, are best made a little on the big side — they’ll grow into them.” She stood by this assessment all her life. In her opinion, young readers were as clever and discriminating as any other.

In 1976, four years after she was interviewed by Hazel de Berg for the National Library of Australia, McFadyen died in Lane Cove in Sydney. Little is known of her later years. She never married and, with few living family members to sponsor her memory, her writings were overshadowed by the immense literary output of children’s authors and illustrators such as May Gibbs, Pixie O’Harris, Mary Grant Bruce, Ida Rentoul Outhwaite and Dorothy Wall. (Unknown to Wall at the time, it was McFadyen who reviewed and revised her manuscript of Blinky Bill for publication.)

Still, hope remains. Parts of McFadyen’s life have been preserved in libraries and archives in Sydney and Canberra. Perhaps some or all of her letters survive in family letter albums and scrapbooks.

Ella McFadyen’s influence was felt more strongly by children than adults — a fact that overshadows the work and achievements of “missing” women all over the world. She was a trailblazer for Australia’s youngest writers, a beloved personality on Sydney’s twentieth-century literary scene, and a lifelong naturalist, able to translate her lofty ideals and love of nature into the language and lore of children. As she wrote in her poem “Adventure,” published in the Sydney Mail in March 1928:

What shall I find at the world’s end

When I lay safely by,

[…]

I spoke with my heart; Sooth and fair,

Shall it be well with me? •

If you have any further information about Ella McFadyen or her family, please contact Emily Gallagher.