Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy 1945–1975

By Max Hastings | HarperCollins | $65 | 752 pages

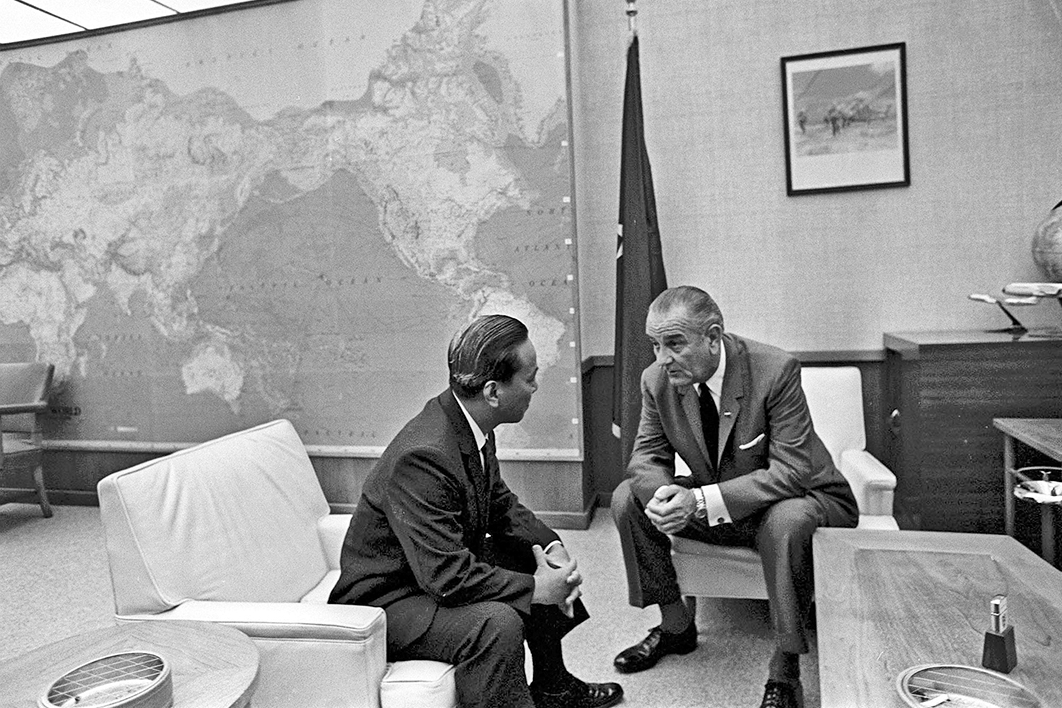

“I am concerned that the Administration seems to have set no limit to the price it is willing to pay for a military victory,” Eugene McCarthy declared in 1968, announcing he would seek the Democratic presidential candidacy as an opponent of the war in Vietnam. Four months later, president Lyndon Johnson, shaken by McCarthy’s performance in the New Hampshire primary — and rattled further by Bobby Kennedy’s entry into the race — went on national television to tell America that he would not seek another term in office.

“The moral issue as I saw it,” McCarthy later reflected, “finally got down to the question of was there any proportion between the destruction and what possible good would come out of it? You started with the judgement… about people in South Vietnam wanting to have a free society. But the price of getting it was the destruction practically of a total community. You make a pragmatic judgement… you don’t pursue it to all-out destruction.”

McCarthy believed, like Johnson, that America’s goal in Vietnam was the defence of a “small and brave nation” against communist aggression; but he concluded that the end did not justify the death and destruction unleashed in its pursuit.

On 16 March 1968, four days after McCarthy’s upset result in New Hampshire and on the day Kennedy declared he was entering the race, American infantry entered the hamlet of My Lai and embarked on an orgy of unprovoked slaughter. At least 504 unarmed South Vietnamese men, women, children and babies died in the indiscriminate violence. Yet when the massacre was eventually revealed, only one soldier, William Calley, was convicted, and he received a sentence of less than four years, under house arrest, for the murder of twenty-two people.

For radical critics of the Vietnam war, atrocities like My Lai indicated that the Americans were not fighting a war in defence of South Vietnam’s freedom; they were fighting the South Vietnamese people themselves. The problem was not the price of such an endeavour but its purpose. The regime in the southern capital, Saigon, did not have a legitimate claim to represent the South Vietnamese people; the loyalties of most South Vietnamese were not with Saigon and the Americans but with the Viet Cong and Hanoi; and the United States was on the side of an autocratic client regime at war with its own people.

“In Vietnam what we were doing was trying to stop a local government from coming to power,” as Frances FitzGerald summed it up in her Pulitzer Prize–winning Fire in the Lake. In a similar vein, Noam Chomsky argued that the United States invaded South Vietnam in a manner analogous to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Which interpretation of the war is correct? McCarthy and Johnson’s? Or Fitzgerald and Chomsky’s? Was America’s war a failed but noble defence of South Vietnam’s freedom or an imperious attempt to obstruct Vietnamese efforts to determine their own destiny? In Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy 1945–1975 prolific British journalist and war historian Max Hastings sides with McCarthy. For Hastings, America’s cause was that of the South Vietnamese themselves; and the goal of preserving a non-communist South — leaving aside the destructive excess with which it was pursued — is deserving of admiration. Over the course of 752 pages, however, he adduces an abundance of evidence at odds with this interpretation, producing the curious effect of a story that refuses to accept its own moral.

Hastings’s narrative begins with France’s palpable desire to stop a local government from coming to power in Indochina in the wake of the second world war. Following closely in the footsteps of Fredrik Logevall’s seminal Embers of War, Hastings shows how deeply implicated the United States was in the effort to re-establish European colonial rule upon Japan’s defeat — and the extent to which the origins of America’s own war in Vietnam are found in the first Indochina war.

Within weeks of president Franklin Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, Harry Truman’s administration settled on a policy of implacable opposition to communist rule in Vietnam from which the United States would not deviate for the next three decades. Contrary to all Roosevelt’s instincts — expressed publicly and privately throughout the war — it determined to support the French campaign to reconquer Indochina. At the San Francisco Conference in mid 1945, secretary of state Edward Stettinius assured the French foreign minister, Georges Bidault — utterly falsely — that “the record is entirely innocent of any official statement of the US government questioning, even by implication, French sovereignty over Indochina.”

When President de Gaulle visited Washington in August, Truman confirmed that inconvenient pronouncements such as the Atlantic Charter (the wartime agreement between Roosevelt and Winston Churchill that supported “the right of every people to choose their own form of government”) had been forgotten. It was only with American air and landing craft that the French were able to send troops back to Indochina in the wake of the Japanese surrender, and Washington gave permission for American matériel, originally designated for use against the Nazis, to be deployed against the Viet Minh.

With the fall of China and the onset of the Korean war, the American commitment to French colonial rule in Indochina intensified. Hastings reports that by early 1951 the Americans were sending the French more than 7200 tonnes of military equipment each month, with an additional 130,000 tonnes delivered in the final quarter of that year. These dry numbers may have barely impinged on the awareness of the American public, but it was a different matter for the Vietnamese.

“All of a sudden, hell opens in front of my eyes,” a Viet Minh commander wrote in his diary. “Hell comes in the form of large, egg-shaped containers, dropping from the first plane, followed by other eggs from the second and third plane. Immense sheets of flames, extending over hundreds of meters, it seems, strike terror in the ranks of my soldiers. This is napalm, the fire that falls from the skies.” For the Vietnamese, American involvement in the first Indochina war was real enough.

When a young senator, John F. Kennedy, returned from a visit to Vietnam in November of 1951, he said in a moment of historic candour: “In Indochina we have allied ourselves to the desperate effort of the French regime to hang on to the remnants of an empire.” But even this forthright acknowledgement of the reality of American foreign policy was rapidly becoming an understatement. In fact, the United States was displacing France as the major proponent of the war. During a visit to Washington in June 1952, the French overseas territories minister, Jean Letourneau, publicly countenanced an armistice with the Viet Minh, reflecting growing French weariness with the war. The Americans were horrified by his proposal for international negotiations along the lines of those occurring at the time in relation to Korea, and Letourneau soon retracted under their intense pressure.

In the same month, American opposition to a French withdrawal, or any negotiated resolution to the conflict, was formalised in a National Security Council statement of policy. “By the end of 1953,” Hastings records, “the new Eisenhower Republican administration was paying 80 per cent of the cost of the war, a billion dollars a year [US$9.4 billion in today’s terms].” It may be impossible to say precisely when, but at some point the first Indochina war had become an American war.

American policy boiled down to a simple syllogism. Vietnam could not be permitted to go communist; independence would result in communist rule; independence could therefore not be permitted. As Kennedy said in his November 1951 speech to the American Friends of Vietnam, “Every neutral observer believes a free election… would go in favour of Ho and his communists.” It was an assessment that anticipated Eisenhower’s candid admission that he had “never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs, who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader.”

Hastings doesn’t question those assessments: in fact, he reports their confirmation by the South Vietnamese head of state, Nguyen Van Thieu, as late as 1965. To paraphrase Kissinger’s remark with respect to Chile, the issues were far too important to be left to the Vietnamese to decide for themselves.

And so, when the French found themselves in a dire position at Dien Bien Phu in early 1954, besieged by General Giap and his Viet Minh forces, Eisenhower and his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, explored every imaginable option to stave off defeat. Using C-119 transports, the CIA flew supplies in to the French, with additional support coming in the form of American-supplied B-26s, serviced by uniformed US air force men. When, despite this vital aid, French collapse appeared inevitable, the US administration considered options ranging from bombing the Vietnamese using B-29 Superfortresses based in the Philippines to a strike with three tactical nuclear weapons. The latter, writes Hastings, was embraced by the chairman of the joint chiefs, admiral Arthur Radford, “as a viable option.”

Ultimately, the White House settled on a plan to send in American forces to carry on the war. Eisenhower supported this option subject to two provisos: congressional support, and allied (primarily British) participation. Congressional leaders signalled that their assent was contingent on the position of allies, but the British were unconvinced. Churchill reportedly responded that, “after Britain had been unable to save India for herself… it was implausible that she could save Indochina for France” — a remark that says much about the character of the proposed undertaking. With Britain sceptical, attention turned to Australia and New Zealand. The Menzies government, if only out of a recognition of the hopelessness of the French position and a desire not to antagonise Britain, resolved that it was time to accept a political solution, to be determined at a conference about to begin in Geneva.

On the evening of 7 May 1954 a unit of Vietnamese soldiers entered the French command post at Dien Bien Phu, detained French colonel Christian de Castries, and raised the red flag of the Viet Minh. For the French, a defeat of this order was so unexpected and so humiliating that it led to the downfall of the conservative government of Joseph Laniel, with his replacement, the radical Pierre Mendès-France, promising to resign if he could not negotiate a French exit from the war in Indochina — now in its ninth year — within thirty days.

Just three days later, on 10 May, the leader of the Viet Minh’s delegation in Geneva, Pham Van Dong, basking in the glow of an historic victory, presented his opening statement to the Geneva conference. The Americans appeared to be in an impossible position. As hostile as they were to Vietnamese independence, the French were on the brink of defeat and they lacked a viable plan for a large-scale intervention of their own.

“To the amazement of the Westerners,” writes Hastings, Dong “expressed willingness to consider partition.” As Hastings observes, “what was extraordinary about subsequent events at the conference tables, was that French humiliation yielded no triumph for the Viet Minh.” The Vietnamese communists were forced to accept the temporary partition of their country, with control south of the seventeenth parallel handed to the American-allied Ngo Dinh Diem. Most disconcertingly, there would be a two-year delay until July 1956, when national elections leading to reunification were scheduled to occur.

Having spent “torrents of blood to strengthen their negotiating position,” the Viet Minh “were eventually obliged to go home with half a loaf.” How, Hastings asks, were the French — and, more importantly, their American and Vietnamese allies — able to snatch a political victory of sorts from the jaws of humiliating military defeat?

It is a perceptive question, the answer to which reveals much about the character of the war that had just ended and the war that was to follow. The immediate explanation for this remarkable turn of events lay in the attitude of the Chinese and the Soviets. “It seems almost certain that the Viet Minh had been heavily pressured by the Chinese and Russians to initiate such a proposal,” Hastings explains. For the two major communist powers, the overriding concern was to avoid another Korea — a scenario in which direct American military intervention would entangle them in another superpower confrontation. When Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai met France’s Mendès-France for bilateral talks in late June, he was candid about China’s main objective of keeping the United States out of Indochina. If the partition of Vietnam would achieve this, it was a price worth paying.

While the Vietnamese communists had contemplated the possibility of some form of temporary partition, they had not envisaged anything like the two-year delay that was ultimately forced on them. In the end, they found themselves without support from either the Chinese or the Russians. Their only brutal alternative was to persevere on the battlefield, for years possibly, in pursuit of total victory. As many in the politburo in Hanoi saw it, Zhou Enlai had sold them out.

But the Russian and Chinese posture at Geneva only reflected the deeper reality that, by 1954, the communists’ principal adversary in Vietnam was no longer France but the United States. Victory at Dien Bien Phu (and in subsequent battles in May and June) made an eventual French exit from the war inevitable and strengthened the communists’ hand at the negotiating table, but it was far short of decisive. As the Russian and Chinese calculations indicated, what really mattered was the American position.

Among all the reasons the United States would not accept a communist Vietnam, the factor that put its credibility on the line was the depth of its involvement in the first Indochina war. The advent of an independent, communist Vietnam, in defiance of the will of the United States, would bring the superpower’s postwar primacy in Asia into question. A decade later, John McNaughton, the US assistant secretary of defense (and Daniel Ellsberg’s boss), would characterise America’s goal in Vietnam as “70 per cent to avoid a humiliating defeat (to our reputation as a guarantor).” Given the prestige and treasure the United States had already sunk in Vietnam by 1954, that estimate essentially applied already.

The Americans never took seriously the stipulation in the Geneva Accords that “the military demarcation line is provisional and should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary.” And they weren’t going to permit Vietnam’s future to be determined by the Vietnamese themselves, at national elections. In the words of the National Security Council shortly after the Geneva Accords had been signed, the United States would “make every possible effort, not openly inconsistent with the US position as to the armistice agreements… to maintain a friendly non-Communist South Vietnam and to prevent a Communist victory through all-Vietnam elections.”

The basic syllogism had been revised: Vietnam as a whole could not be permitted to go communist; unification and national elections would allow that to happen; therefore unification and national elections had to be prevented. The partition of Vietnam — along with a friendly client regime in Saigon — had replaced French colonial rule as America’s stratagem for preventing the communist ascendancy. America had found a way of continuing the war, lost on the battlefield, by other means.

To begin in 1945 and review the history of America’s gradually deepening hostility to Vietnamese self-determination is to largely settle the debate about the nature of America’s war in Vietnam, and about whether it was a response to external aggression or an instance of it. South Vietnam was not a “small and brave nation”; it was a neo-colonial artifice designed to thwart the will of a nation. South Vietnam was born of the American refusal to accept a conclusion to the first Indochina war and its corollary, that the Vietnamese people would determine their own destiny.

Of course, many Vietnamese vehemently opposed the communists and did not want to live under their rule. Among the ample evidence for that is the exodus south of almost one million people, mostly Catholics, in the immediate aftermath of the country’s partition. But the Geneva Accords offered a process that all parties could reasonably be expected to respect: negotiated compromise and the ballot box. It was the United States and Ngo Dinh Diem who refused to accept such a process, and it was the American refusal that was decisive. The Americans ended up fighting on one side of a civil war, but they, more than anyone else, had ensured that a political conflict became a military one. As Hastings acknowledges, “Most South Vietnamese, and especially the Buddhist leadership, would have chosen peace on any terms; it was their American sponsors who rejected such an outcome…”

In time, the communists discovered that their enemies would refuse to honour the compromise they had reluctantly accepted at Geneva. When the party’s general secretary, Le Duan, returned to Hanoi from a clandestine visit to the South in January 1959, he reported to the politburo that their southern comrades were accusing them of cowardice, bitter that they were being left to fight the battle against Diem on their own.

At this point, Hanoi made the fateful decision to support armed struggle in the South by opening up the supply routes through the Annamite Range, which became known as the Ho Chi Minh trail. Resolution 15, as the decision was called, was adopted on 22 January 1959. On 8 July, Viet Cong guerrillas launched an attack on American servicemen stationed near Bien Hoa, thirty kilometres northeast of Saigon. The names of the two Americans killed, Chester Ovnand and Dale Buis, later became the first to be listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington.

By 1962, American helicopters and tanks were being shipped to the South en masse, Green Berets were sent to organise the Montagnards, and the US air force had embarked on its wholesale destruction of the Vietnamese countryside, primarily by spraying it with Agent Orange. By the time of Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, 16,000 American military advisers were in South Vietnam.

In the final pages of Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy, Max Hastings imagines the events of 1959 taking a different turn. It is “interesting to speculate upon the consequences, had the North Vietnamese refrained from sponsoring armed struggle in the South,” he ruminates. “Plausibly, the indigenous National Liberation Front could have been contained.” Taking the scenario a step further, he evinces his basic sympathy with the American objective of preserving the South under the rule of a non-communist dictatorship: “In many other Asian countries between 1960 and 1990, authoritarian military rule gave way to democracy.”

He views the war that ensued as a kind of moral tie, in which both sides stand condemned: the communists for seeking to unite Vietnam under their rule; the Americans for resisting this effort with a level of violence that could not ultimately be justified. “The communists and the United States rightfully share responsibility for the horrors that befell Vietnam after the death of John F. Kennedy,” he concludes, “because both preferred to unleash increasingly indiscriminate violence, rather than yield to the will of their foes.”

Given the history he has rehearsed, it is a remarkable assessment. The Geneva Accords had been achieved after almost a decade of war, a war against two world powers in which an improbable victory had been won through incredible sacrifice. Around 200,000 Vietnamese soldiers and even more civilians had lost their lives. If the Viet Minh and Viet Cong had yielded to the will of their foes in 1959, they would have been submitting to the artificial division of their country, a division imposed on them by a foreign power contrary to the will of a majority of their compatriots.

They would also have been meekly accepting that the compromise forged at Geneva — an agreement binding in international law, which they fought for and made in good faith — would be completely disregarded. All the while, opponents of Diem’s regime would continue to be subjected to arbitrary arrest and execution. In other words, it is implausible to imagine that they would have simply yielded to the will of their foes, and unreasonable to claim that they should have. To see this, it is only necessary to ask whether we would accept such a scenario in our own country.

Hastings’s position is all the more surprising given his own argument that, in taking the war to Diem’s regime in Saigon, the Vietnamese communists were not doing anyone’s bidding but their own. “It was significant that Hanoi was slow to inform the Russians about Resolution 15,” writes Hastings, “because Le Duan and his comrades knew how unwelcome it would be.” The United States “entirely misjudged the attitudes of Moscow and Beijing, supposing their leaderships guilty of fomenting the rising insurgency,” he observes. “Instead, until 1959 resistance to the Saigon regime was spontaneous and locally generated. For some time thereafter, it received only North Vietnamese rather than foreign support.”

Zhou Enlai reportedly upbraided Le Duan on a 1961 visit to Hanoi. “Why are you people conducting armed struggle in South Vietnam?” he asked. “If the war expands into the North, I am telling you now that China will not send troops to help you fight the Americans… You will be on your own, and have to take the consequences.” Ultimately, the Vietnamese weren’t left on their own: hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers were sent to North Vietnam, while the Soviets primarily provided matériel. But the involvement of the communist powers didn’t precede or precipitate American intervention; it followed it.

The great irony is that at the very point American leaders were espousing the domino theory, the Chinese and the Russians were trying to hold the dominoes back. When the Americans bombed the North following the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964, Moscow and Beijing didn’t send Hanoi sympathy cards but scolded them for having provoked the Americans. The message was reiterated by Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin when he visited Hanoi in early 1965. “The Russians were desperate to avoid further entanglement,” writes Hastings. The Americans weren’t fighting foreign aggressors in Vietnam but its indigenous independence movement.

Nothing is more demonstrative of Saigon’s submission to Washington than the American propensity to overthrow its leaders whenever they were no longer serving US purposes. The best known, the coup against Diem in 1963, has a revealing prehistory. In mid 1955, Eisenhower’s personal envoy, General Joseph Collins, made an assessment that Diem was not up to bringing the gangs and sects that then dominated Saigon into line. “At 6.10pm on 27 April 1955,” writes Hastings, “Dulles sent a cable from Washington to Saigon authorising the prime minister’s removal, much as he might have ordered the sacking of an unsatisfactory parlourmaid.” The directive was only rescinded after Diem’s army prevailed in a street battle that evening and the American mood changed.

When Diem was ultimately overthrown and killed in November 1963, the Americans greenlighted the coup partly because Diem and his brother, Nhu, were rumoured to be countenancing détente with the North. “The most ignoble aspect of Washington’s mounting interest in a coup was the impetus provided by fears that Diem or his brother Nhu might be contemplating a deal,” writes Hastings. “Charlie, I can’t let Vietnam go to the Communists and then go and ask [American voters] to re-elect me,” Kennedy reportedly told his friend Charles Bartlett.

Diem’s demise was not the last time the United States supported a coup against its South Vietnamese client because of fear it might be open to negotiations with the enemy. Hastings describes much the same scenario when Diem’s successor, General Duong Van Minh, was replaced by General Nguyen Khanh just three months after Diem’s demise. By January 1965, the Americans became concerned that Khanh, in turn, was in league with the Buddhists. “The most sinister aspect” of the relationship, wrote ambassador Maxwell Taylor, was that it “may be an important step towards the formation of a government which will eventually lead the country into negotiations with Hanoi and the National Liberation Front.” When General Khanh had the audacity to refuse to meet an emissary from Lyndon Johnson, the president flew into a rage. “The Americans began to search frantically, farcically, for a replacement,” Hastings reports. Nguyen Van Thieu, South Vietnam’s president from 1967 until its dissolution, was “haunted by the memory of Diem, fearing that if he defied the will of Washington, he would meet the same fate.”

Nor did the Americans bother to consult, or even inform, Saigon about other key decisions. Of the landing of US marines near Danang on 8 March 1965, Hastings observes: “A significant aspect of the Marines’ landing, before a throng of photographers, excited children and pretty girls distributing garlands of flowers, was that nobody in Washington, the US embassy or MACV [Military Assistance Command, Vietnam] saw fit to inform the South Vietnamese government that they were coming.” President Thieu was not even apprised of the Nixon administration’s policy of Vietnamisation — a matter of some consequence to South Vietnam — prior to its announcement. “Without any Saigon representative commanding a serious hearing” at the Paris peace talks, Hastings acknowledges, “the communists were scarcely unjust in branding Thieu and his associates as ‘US puppets.’”

The closest Hastings comes to conceding that the conventional picture of the war was a mirage is to cite the opinion of Paul Warnke, assistant secretary of defense under McNamara and then Clark Clifford. Warnke “thought that the whole story might have turned out better if Washington had imposed an honest-to-God occupation, rather than merely sought to hand-hold a grossly incompetent local government: ‘What we were trying to do was to impose a particular type of rule on a resistant country. And that required occupation, just as we occupied Japan [in 1945].’” Hastings responds that “Warnke missed the obvious point, that such a policy would have required treating the South Vietnamese as a conquered people, rather than as citizens of a supposed sovereign state.” But Hastings’s own catalogue of contempt, coups and atrocities shows the Americans did treat the South Vietnamese like a conquered people.

As his counterfactual account of the events of 1959 indicates, Hastings believes that if the United States had been successful in enforcing the partition of Vietnam and sustaining the dictatorship in Saigon, a modern-day South Vietnam could be another South Korea. The alternative was “to concede victory to the communists [and] condemn the Vietnamese people to an ice-age future under Le Duan’s collectivist tyranny, such as eventually became their lot after 1975.”

It is true that the domination of Vietnam’s independence movement by adherents of an authoritarian ideology was a wicked problem, not least because any election they won was likely to be the last election for a long time. One of the strengths of Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy is that it comprehensively documents the cold-blooded authoritarianism of the Hanoi regime, including essential Vietnamese perspectives like that of Truong Nhu Tang, who served as justice minister in the Provisional Revolutionary Government only to flee Vietnam three years after reunification. But the United States has to take its share of the blame for the way events unfolded from 1945.

In the immediate wake of the second world war the United States faced a historic window of opportunity. Acting as a true friend of the Vietnamese people, it could have helped them achieve both national sovereignty and sovereignty over their nation.

When Ho Chi Minh proclaimed Vietnam’s independence in Ba Dinh Square on 2 September 1945, he began with words that echoed America’s own declaration: “All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” Three days earlier, he had written to President Truman, requesting Viet Minh participation in Allied deliberations on the future of his country. It was the first of around a dozen letters from Ho to the American president that went unanswered. As late as 28 February 1946, in the wake of French moves to reassert control in Hanoi, Ho wrote to Truman: “I… most earnestly appeal to you personally and the American people to interfere urgently in support of our independence and help making [sic] the negotiations more in keeping with the principles of the Atlantic and San Francisco Charters.” Again, he received no reply.

If Truman had engaged Ho, if the United States had supported Vietnamese independence and opposed a French return, as Roosevelt had envisaged throughout the war, the United States could have insisted on a commitment to free and fair elections in return for its support for self-determination. A peaceful path to power could, in turn, have strengthened the hand of moderates and isolated the incorrigible authoritarians. There are many reasons why such a policy might have failed, but it would have stood a much better chance of ultimate success than the course America actually took.

In seeking to impose its will on Vietnam, first by backing the French and then by rejecting the Geneva Accords, the United States introduced a logic of violence that only empowered hardliners. The Americans not only failed to recognise that Ho was a nationalist as well as a communist but, more critically, they also failed to appreciate that their own policy left Vietnamese nationalists with little choice but to throw in their lot with Ho. Ho Chi Minh had the overwhelming support of his compatriots in 1954 because he had just led his people in a triumphant decade-long war of resistance against foreign occupation. To support Ho, one only had to be a patriot.

In the years following the Geneva Accords, Ho and Giap were genuinely committed to securing the reunification of their country peacefully, but America made it clear that reunification was not going to happen without armed conflict. As a result, Hanoi radicalised. Ho was kicked upstairs to figurehead status; Giap was sidelined; and, in late 1957, the ruthless and uncompromising Le Duan was elected as party secretary. The hardest of hardliners had got control and would shape communist policy during the American war and its aftermath. But America had signalled that compromise was folly. What did it expect?

Eschewing the unpalatable implications of Warnke’s characterisation of the war, Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy oscillates between two kinds of confusion: one about what America did in Vietnam, the other about what it ought to have done — between the unsustainable pretence of a defensive war, on the one hand, and an imperial arrogance that dare not speak its name on the other. It was a case, in Charles de Gaulle’s phrase, of the American “will to power, cloaking itself in idealism.” Hastings does not criticise American aggression in Vietnam any more than Eugene McCarthy did, because he only sees the cloak, a failed but noble attempt to defend South Vietnam.

When Hastings turns to advancing what he sees as the lesson of the Vietnam war, he only reiterates the mistake. As numerous reviews have noted, Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy concludes with the words of Walt Boomer, who served as a marine in Vietnam before becoming a four-star general in command of US forces in the Gulf war. “It bothers me that we didn’t learn a lot. If we had, we would not have invaded Iraq,” Boomer says. These final words have been received as an enlightened affirmation of the folly of war and a prudent condemnation of US adventurism.

What is the lesson of Vietnam, according to Hastings? “It is among the themes of this book,” he writes, that “the foremost challenge” for the United States “was not to win firefights, but instead to associate itself with a credible Vietnamese political and social order.” Here, he sees the parallel with Iraq: “In the absence of credible local governance, winning firefights was, and always will be, meaningless.”

Hastings fails to recognise that any political and social order that requires the approval of a foreign power would lack credibility, and that any elite that owed its existence to a foreign power would not be responsive to the interests of the people. It is no coincidence that, as one American reporter put it, Diem and his successors had no relationship with their own people. That was their job description.

The lesson of Vietnam is that it is wrong to try to dominate another people, and it is wrong to commit aggression. But to learn that lesson, first aggression must be seen for what it is. Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy never fully faces up to the reality that the United States was trying to impose its will on Vietnam — or the consequences of that reality — and so it doesn’t succeed in shedding the illusions under which the war was fought. The domino theory profoundly misrepresented Moscow and Beijing, the Viet Minh and the Viet Cong, but its deepest misunderstanding concerned the United States itself. •